Abstract

Background. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is widely used in many fields such as food, cosmetics, and paper industries. Studies on the photocatalytic properties of TiO2 on living tissue are limited.

Objectives. To examine the histopathological effects of TiO2 solution on the marginal veins of rabbit ears under ultraviolet (UV) light.

Materials and methods. In this study, 4 groups of rabbits (8 rabbits per group) were used: the 1st group was the control group, the 2nd group received 20% of nano-TiO2 only, the 3rd group received UV light only, and the 4th group received nano-TiO2 and UV light, simultaneously. The study lasted for 14 days and samples were taken from the marginal ear vein on the 15th day.

Results. The ear tissues of rabbits in the control and TiO2 groups showed a normal histological appearance. In the UV group, the results showed severe chronic inflammation due to mononuclear cells around the hair follicles and perivascular areas. However, these findings decreased in the UV/nano-TiO2 group.

Conclusions. The method applied in this study can be used in the treatment of telangiectasia in the future. However, this study investigating the effects of nano-TiO2 on vascular structures under UV light had a predominantly histological and observational nature. Further studies involving genetic, cytogenetic, biochemical, histochemical, and immunohistochemical analyses need to be performed to test the theories we proposed.

Key words: animal model, titanium dioxide, vein, nano-TiO2, ultraviolet light

Background

Titanium dioxide (TiO2), also known as titania, is widely used in many fields such as paints, cosmetics, food products, and pharmaceuticals. With the discovery of the photocatalytic activity of TiO2, the use of this material has expanded.1 Titanium dioxide can be found in many crystalline structures in nature, but it has 2 basic structures: the rutile and anatase polymorphic phases. Titania also has many favorable properties such as semiconductivity, non-toxicity, white color, low cost, chemical stability, and photocatalytic activity.

The nano-TiO2 electron band gap is higher than 3 eV and has a high absorption in the ultraviolet (UV) region. However, due to its strong optical and biological properties, it can be used in UV light protection applications. Many studies have been conducted to examine the photocatalytic activity of TiO2.

Photocatalysts can be defined as semiconductors that become active when interacting with light, forming strongly oxidized or reductive active surfaces. Sunlight promotes the purification of water systems in nature, such as rivers, streams, lakes, and pools. The sunrays initiate the breakdown of large organic molecules into smaller, simpler molecules. This breakdown reaction eventually results in the formation of carbon dioxide, water and other molecular products. The results of laboratory studies in the early 1980s indicated that semiconductors accelerated this natural purification process induced by sunlight.2

High-efficiency photocatalysts under UV light also have high efficiency under visible light when various methods are applied. The S-doped TiO2 has high photocatalytic activity under visible light.3 For example, S-doped TiO2 has high efficiency at a 500 nm wavelength, while Ru-doped TiO2 has high photocatalytic activity at a 440 nm wavelength.3

Studies on the photocatalytic properties of TiO2 on living tissue are limited. To address this research gap, this study investigated the histopathological effects of TiO2 on the superficial veins of rabbit ears under UV light by utilizing its photocatalytic properties.

Objectives

Photocatalysts, which are commonly used for cleaning the environment, water and air, are now being used in different fields. Watanabe et al. evaluated the photocatalytic activity of nano-sized TiO2 in an artificial skin model.4 They sequentially measured the CO2 levels on artificial skin with the addition of nano-sized TiO2, and found an increase in ambient CO2 level with photocatalytic activity. Shen et al. encapsulated TiO2 with zeolite to increase its photocatalytic activity in sunscreens, and found that the harmful effects of UV light were minimized.5

The present study aimed to investigate the effects of nano-sized TiO2 on superficial veins under UV light with a 368 nm wavelength in a rabbit model.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Sivas Cumhuriyet University (Sivas, Turkey; approval No. 65202830-050.04.04-62). All procedures were carried out at Sivas Cumhuriyet University Laboratory of Experimental Animals in accordance with the local rules of care and use of experimental animals.

The study was conducted as a controlled randomized animal experiment. This study employed a total of 8 male and female New Zealand white rabbits from 6 to 8 months of age. The rabbits weighed between 3.2 kg and 3.5 kg for males and between 2.75 kg and 3 kg for females. All animals were fed a standard laboratory diet with free access to water. The rabbits were housed with 1 animal in each cage. Rabbits that were able to perform their normal activities in the cages were kept in rooms with a temperature of 22 ±2°C, a humidity level between 50% and 70%, and a 12 h day/12 h night cycle. All animals were kept under observation for 1 day to determine whether they were healthy before the experiments. Healthy animals without any problems were included in the study.

The rabbits were divided into the following 4 groups (8 rabbits per group; Table 1):

– group 1 – control group: no treatment was performed;

– group 2 – 20% nano-TiO2 group: 0.2 mL of nano-sized 20% TiO2 solution was topically applied to the visible marginal vein of the right ears of the rabbits every day. No other procedure was performed;

– group 3 – UV group: rabbits were exposed to ultraviolet A (UVA) light at a wavelength range of 368 nm for 12 h a day, at a distance of approx. 150 cm. No other procedure was performed;

– group 4 – 20% nano-TiO2 and UV light group: 0.2 mL of nano-sized 20% TiO2 solution was topically applied to the visible marginal vein of the right ears of the rabbits every day. Simultaneously, UVA at a wavelength of 368 nm at a distance of 150 cm was applied for 12 h a day.

The procedures were performed for 14 days (Figure 1). On the 15th day, punch biopsies were taken from the marginal vein under local anesthesia from all groups. The samples were then examined histologically.

For the nano-TiO2, 20 nm TiO2 powder with the tradename Degussa p25 (Nanoshel LLC, Wilmington, USA) was used. The UVA light sources were Sylvania brand UV lamps (Erlangen, Germany), measuring 40W/4FT/T12/BL368 with a wavelength of 368 nm. No treatment or euthanasia was performed on the animals at the end of the study.

Histopathological examination

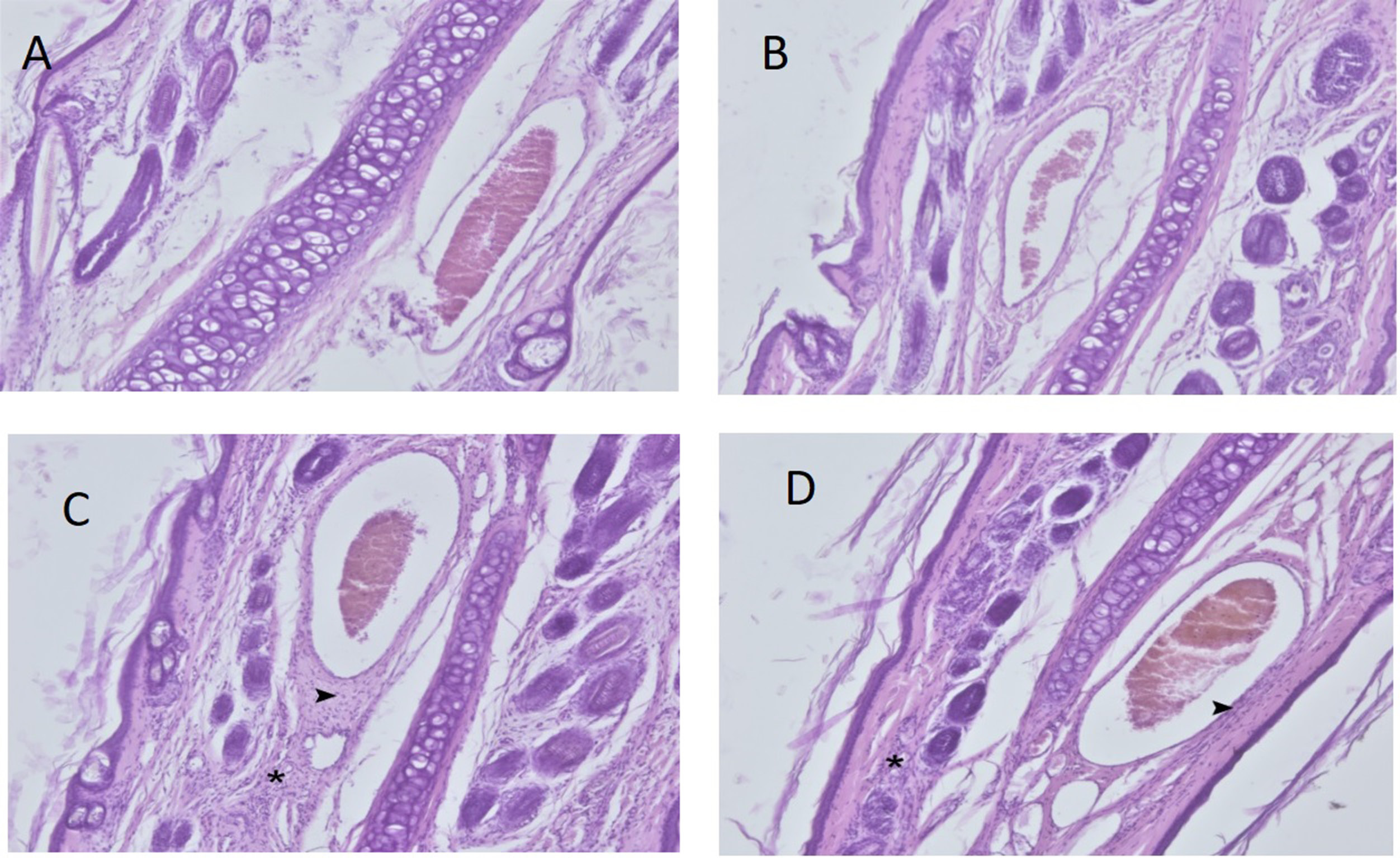

The ear tissue samples from the rabbits were placed in 10% buffered formalin solution. The samples were then subjected to routine follow-up procedures and embedded in paraffin blocks. Next, the 5-µm sections taken from the blocks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to assess histopathological changes. Sections were examined under a light microscope and semi-quantitatively scored as negative (−), mild (+), moderate (++), or severe (+++) for chronic inflammation. The increase in macrophage and lymphocyte density in the tissue was used as a chronic inflammation marker. We evaluated the vascular samples and scored them according to the histopathological scale described by Kuwahara et al.6

Statistical analyses

Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) and SPSS v. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) were used to perform the statistical analysis. Based on an α of 0.05, β of 0.20 and 1-β of 0.80, we decided to include 8 rabbits in each group (32 rabbits in total) and the power was calculated to be 0.8345. Since the distribution of the data was not normal, the Kruskal–Wallis H test was conducted to assess significant differences between groups. For post hoc tests of differences between groups, Dunn’s post hoc test was used, because it preserves the pooled variance for the tests implied by the Kruskal–Wallis null hypothesis (Table 2). When the data violated the normality assumption (Table 3), we decided to use the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test to compare the mean rank scores of the groups. The effect size for the test was calculated as 4.92.

Results

Four female and 4 male rabbits were included in each experimental group; thus, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of gender (p > 0.05). The results showed that the ear tissues of the rabbits in the control and nano-TiO2 groups had a normal histological appearance (Figure 2). However, we observed the formation of severe chronic inflammation of mononuclear cells in the perivascular areas and around the hair follicles in the UV group (Table 4).

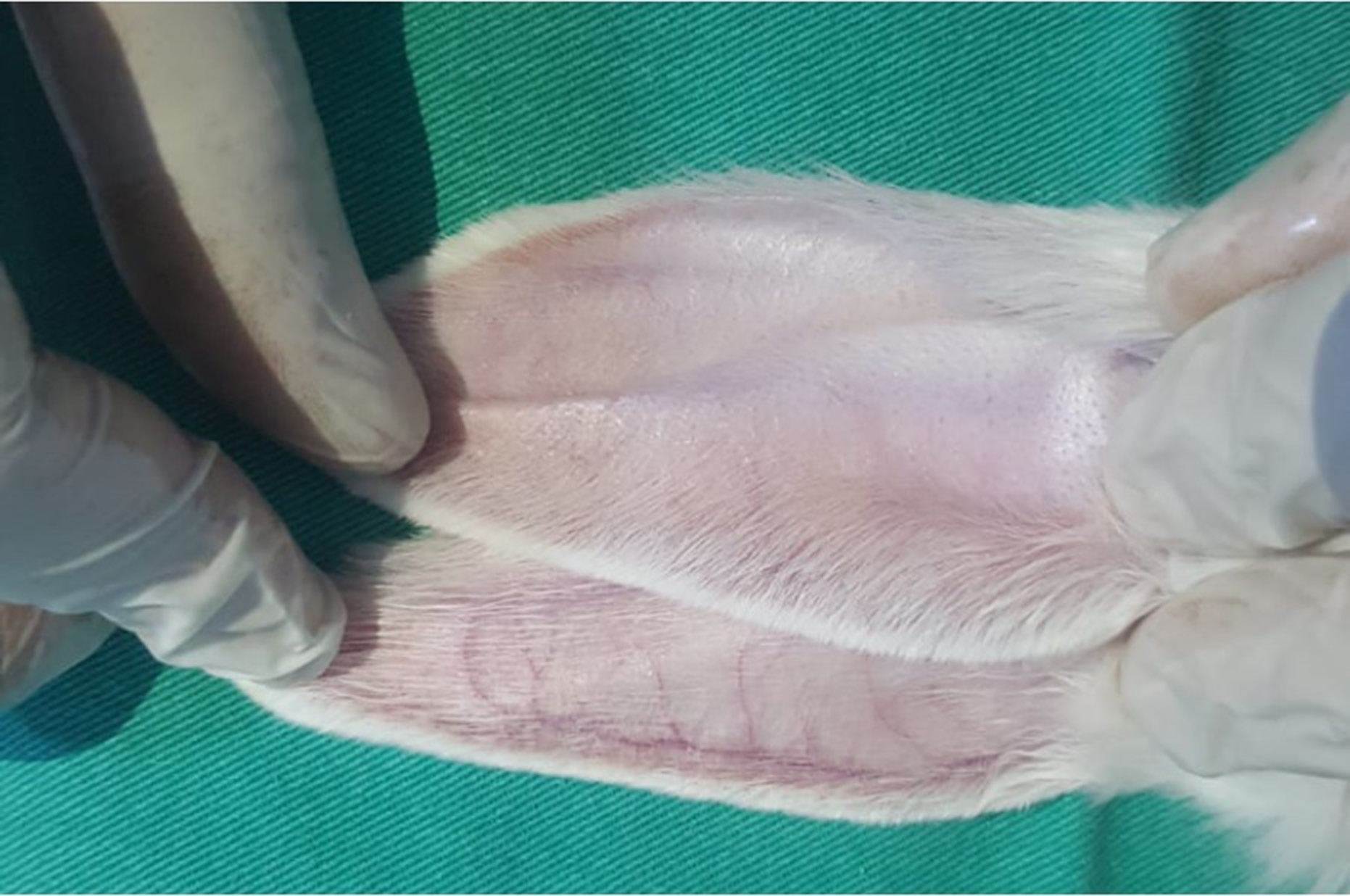

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis H test indicated significant differences between groups subjected to different treatment methods (χ2(3) = 27.835, p < 0.001), with mean rank scores of 9.12 for the control group, 8.06 for the 20% nano-TiO2 group, 28.06 for the UV group, and 20.75 for the group administered both 20% nano-TiO2 and UV. Dunn’s pairwise post hoc test indicated significant differences between the control group and the UV group (p < 0.001), between the 20% nano-TiO2 group and the UV group (p < 0.001), between the 20% nano-TiO2 group and the group administered both 20% nano-TiO2 and UV light (p = 0.004), and between the control group and the group administered both 20% nano-TiO2 and UV light (p = 0.009). There were no other significant differences (Table 5). The histopathological changes decreased in the group that received both UV and nano-TiO2. Macroscopically, the results indicated that the visibility of rabbit ear veins decreased in the 20% nano-TiO2 and UV light group (Figure 3).

Discussion

At present, TiO2 is widely used in many industries such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics (especially in sunscreens), food, biomedical products, etc. Given its wide use, it is necessary to investigate the toxicological and histological effects of nano-TiO2, as well as its effects on the immune system. Fabian et al. administered titanium dioxide nanoparticles intravenously to rats and found that they did not cause any toxic effects at a 5 mg/kg dose and could be used safely at this dose.7 Warheit et al. administered 300 nm of titanium dioxide via inhalation in rabbits and showed that short-term exposure did not cause any lung problems.8 In the same study, they reported that TiO2 of this size had no genotoxic effect and did not cause any irritation of the skin, but reversible conjunctival redness in the eyes of rabbits was observed. In a review of the effects of nano-sized TiO2 on the lung, size, exposure time, and the amount of nano-titanium were identified as the most important risk factors.9

In a wide-ranging review, Iavicoli et al. investigated the effects of nano-TiO2 on mammals organ by organ and system by system.10 Although they discussed the effects of nano-TiO2 on many systems, they emphasized that their effects on vascular structures were not clear. However, they stated that the effects of TiO2 were directly related to the way it was administered, its dose, duration, and particle size. Tang et al. examined the relationship between administration routes and doses of TiO2.11 They found that TiO2 with a size of 5 nm could be passed to the blood intratracheally; when it reached a dose of 0.8 mg/kg, it could reach the lungs and kidneys and it changed liver and kidney function. However, they observed that these effects were reversible after 1 week without permanent damage.

There is a limited number of studies on the effects of TiO2 on vascular structures in the literature. In a study using porcine pulmonary artery endothelial culture, Han et al. reported that nano-TiO2 increased the inflammatory response in endothelial cells.12 They concluded that the increased inflammation response occurred via the redox-sensitive cell signaling pathway.

Montiel-Dávalos et al. conducted a study on human umbilical vein endothelial cell culture (HUVEC) and found that TiO2 inhibited the proliferation of endothelial cells and accelerated apoptotic and necrotic death.13 Alinovi et al. also conducted a study using HUVEC and found that TiO2 nanoparticles increased inflammation in endothelial cells.14 Park et al. conducted a study using a mouse endothelial cell culture line and evaluated whether the size of the nanotube affected the endothelial adhesion and apoptosis rates of TiO2 nanotubes.15 They observed more endothelial adhesion, less apoptosis, and less inflammation in 15 nm nanotubes. Furthermore, their results indicated an increase in inflammation and apoptosis as the size of the nanotubes increased. These findings demonstrate the importance of size in terms of the effectiveness of nano-TiO2 to be used in vascular implants. Ge et al. conducted a study using HUVEC and their results indicated that thin film nano-TiO2 provided laminin immobilization and an increase in endothelial adhesion.16

Ultraviolet light has been used in the treatment of skin diseases since the beginning of the 20th century. Although the mechanism of UV light action is not clear, hypotheses that it increases cell proliferation, epidermal thickness and blood flow in cutaneous capillaries have been proposed.17 In a study that applied UV light to patients with venous ulcers, Dodd et al. concluded that UV light had no benefit in the treatment of venous ulcers.18 However, they observed that UV light increased skin oxygen permeability and inhibited normal vasoconstrictor response.

When light treatment is required in medicine, the preferred UV light wavelength is in the 300–320 nm range. In dermatology, psoralen ultraviolet A (PUVA) treatment for psoriasis, eczema, vitiligo, and cutaneous lymphoma is widely used.19 Although UV light has positive results when applied to appropriate patients for a certain period of time, dose and treatment, excessive exposure can lead to many adverse conditions such as skin cancer, T cell damage, immune depression, sunburn, and premature skin aging.20

Telangiectasias are enlarged venous vessels with a diameter of 0.5–1 mm near the skin surface. Telangiectasias are enlarged postcapillary venules located in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis with histologically complete meaning.21

Engel et al. conducted a field study with a large population in the USA and found that the rate of telangiectasia in the legs was 29–41% in women and 6–15% in men.22 Facial telangiectasia affects tens of millions of people around the world.23 Sclerotherapy is the standard approach for the treatment of telangiectasias. Sclerosis of the telangiectatic vein is the main target in sclerotherapy. In order to achieve sclerosis, various chemical sclerosing agents are administered directly into the enlarged telangiectatic vein, resulting in the formation of a thrombosis and endothelial damage within the vein.24

Apart from sclerotherapy, many different laser treatments, such as argon ion lasers, diode lasers and intense pulsed light sources, are applied.25, 26 Laser treatment was first performed in the treatment of telangiectasias in 1960 using light at a 694 nm wavelength, followed by different systems and wavelengths.27 The underlying logic of laser treatment in telangiectasia is to cause the loss of veins close to the skin surface by creating thermal damage to the vascular structures through the heat generated by UV light. Hemoglobin in the vessel absorbs light best at 418 nm, 542 nm and 577 nm wavelengths.28 However, the wavelengths used in the treatment of vascular lesions are usually 488 nm and 600 nm.28

Photocatalysts can be described as semiconductors that create a strongly oxidized environment on the surface through the effect of UV light. Therefore, photocatalysts can cause degradation in organic tissues close to the region where they are applied. Among the known semiconductor photocatalysts, TiO2 is widely used due to its high activity, high stability under lighting, nontoxic nature, and low price. Titanium dioxide performs its photocatalytic effect best under 340 nm wavelength light, but a wavelength range of 320–380 nm is also good for photocatalyst activity.29

In general, studies have demonstrated that organic cell degradation increases as the wavelength decreases. This means that at a wavelength of 280 nm or less, TiO2 has its maximum photocatalytic effect, leading to the degradation of DNA and RNA.30, 31 Therefore, the light wavelength selected in our study was in the range of 320–380 nm. The same ultraviolet light wavelength and application methods used in previous animal experiments, as well as the dose, concentration, and routes of TiO2 administration were applied in the current study.32, 33 What distinguishes this study from the other studies is that we investigated the effects of TiO2 and UV light on vascular structures simultaneously.

Photodynamic therapy, especially in dermatology and plastic surgery, is used effectively and widely for the treatment of many dermatological diseases in the form of a combination of light and various creams applied to the skin. The main principle of creams with methyl aminolevulinate as the active ingredient is to be absorbed by the skin and subcutaneous tissue, and to provide local apoptosis with the effect of light. In fact, Galvão found that telangiectasias on the face were not visible after photodynamic therapy in a patient with facial actinic keratosis.34

Photodynamic therapy consists of 3 main elements: a photosensitive material, a light source and oxygen. When these 3 factors are combined effectively, they can be applied for the successful treatment of many skin lesions. In photodynamic therapy, the therapeutic effect is achieved by a slight activation of a light-sensitive substance, and reactive oxygen intermediates are formed in the presence of oxygen. These intermediates irreversibly oxidize the essential cellular components that cause apoptosis and necrosis, thereby providing the treatment of lesions on the skin.35 Essentially, our study has shown similar results to photodynamic therapy. In this sense, the study demonstrated that substances with photocatalytic activation may be an appropriate choice for this treatment.

Limitations

The method applied in the present study could be used in the treatment of telangiectasia in the future. However, our study has a predominantly histological and observational nature. Further studies involving genetic, cytogenetic, biochemical, histochemical, and immunohistochemical analyses are needed to test the theories described above.

Conclusion

The results of this study revealed that nano-TiO2 protected the skin and the main vascular structures close to the skin from the harmful effects of UV light. Furthermore, this study determined that telangiectatic structures close to the skin were not observed in the UV and nano-TiO2 group.

Several theories were put forward regarding the absence of telangiectatic structures in the rabbit ear on macroscopic observation. The 1st is that nano-TiO2 and UV light induced apoptosis in telangiectatic structures, just as in photodynamic therapy. The 2nd is that thermal damage was caused by heating during the photocatalytic activation of nano-TiO2. The 3rd theory is that collagen tissue deposited under the epidermis compressed the telangiectatic veins or precipitated them towards the dermis. The 4th is damage of hemoglobin in the telangiectatic vein. The 5th is selective photothermolysis that led to panendothelial obliteration. Any combination of these theories, or some other mechanism of action, may have led to these results.