Abstract

Background. Bevacizumab-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition may lead to a decrease in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels, an increase in intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations and an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, as well as to cell damage.

Objectives. To investigate the biochemical and histopathological effects of ATP, benidipine and ATP in combination with benidipine on bevacizumab-induced kidney damage in rats.

Materials and methods. Rats were divided into 5 treatment groups: bevacizumab (BVZ) alone, ATP + bevacizumab (ABVZ), benidipine + bevacizumab (BBVZ), ATP + benidipine + bevacizumab (ABBVZ), and healthy controls (HC). Adenosine triphosphate (25 mg/kg), benidipine (4 mg/kg orally), ATP (25 mg/kg) + benidipine (4 mg/kg), or saline were administered to albino Wistar rats. One hour after treatment, bevacizumab was injected at a dose of 10 mg/kg to induce kidney damage. Two doses of bevacizumab were delivered 15 days apart. Adenosine triphosphate + benidipine were administered once a day for 1 month.

Results. Malondialdehyde (MDA), total oxidant status (TOS), creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels of the BVZ, BBVZ, ABVZ, ABBVZ, and HC groups were ranked from highest to lowest. Conversely, total glutathione (tGSH) and total antioxidant status (TAS) kidney tissue values were ranked from lowest to highest, respectively. Hemorrhage, tubular necrosis and grade 3 focal tubular atrophy were observed in the BVZ group. Atrophy and grade 2 necrosis were observed in the BBVZ group and atrophy and grade 1 necrosis were observed in the ABVZ group. Only grade 1 atrophy was observed in the ABBVZ group.

Conclusions. Adenosine triphosphate reduced bevacizumab-induced renal toxicity significantly more effectively than benidipine. However, the combination of ATP + benidipine further reduced bevacizumab-induced renal toxicity relative to benidipine or ATP alone. These data indicate that ATP + benidipine might be a potential therapeutic strategy for the prevention of bevacizumab-induced renal toxicity.

Key words: bevacizumab, rat, nephrotoxicity, ATP, benidipine

Background

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal hybrid antibody that binds and neutralizes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).1 Inhibition of VEGF signaling is a common therapeutic strategy in oncology for the development of new drugs.2 Bevacizumab and other anti-VEGFs that have been successfully used in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and colorectal cancer have become some of the most prescribed drugs in the present day.3 Bevacizumab and other VEGF-targeting monoclonal antibodies are also used intravitreally for the treatment of exudative macular degeneration.4 However, the development of overt proteinuria, new-onset hypertension and nephrotic syndrome have been frequently reported during bevacizumab therapy.1 The latest data demonstrate that even intravitreal injections of VEGF inhibitors lead to significant systemic absorption and a measurable decrease in the VEGF activity, and this event has been reported to result in hypertension, proteinuria, glomerular disease, and thrombotic microangiopathy.5 Even though bevacizumab-associated glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome have been confirmed by means of renal biopsy, the mechanism of action has not yet been clarified.1 However, the data cited above suggest that bevacizumab nephrotoxicity is due to decreased VEGF.

There are data in the literature showing that VEGF increases intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels and reduces the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).6 These findings also suggest that decreased VEGF may result in decreased ATP levels and increased ROS production. Decreased ATP causes the inhibition of the Na+/K+-ATPase pump in the cell membrane and, consequently, increases in intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations.7 Increased levels of Ca2+ induce ROS production and cause the Ca2+ channels to open. This event leads to further increases in intracellular calcium levels and cell toxicity.8, 9 These data indicate that bevacizumab nephrotoxicity may cause increased intracellular Ca2+ levels and ROS as a result of decreased ATP.

Previous work has shown that ATP is a molecule mostly produced by oxidative phosphorylation under aerobic conditions in mitochondria.10 Chiang et al. have reported that ATP elevates VEGF levels and promotes epithelization.11 Here, we evaluate the effects of benidipine, an L-type calcium channel blocking antihypertensive agent,12 on bevacizumab-induced kidney damage. It has been previously reported that benidipine prevents an increase in oxidant parameters and has positive effects on antioxidant levels in damaged tissues.13

Objectives

The data cited above suggest that an ATP and benidipine combination may be useful in the treatment of bevacizumab-associated nephrotoxicity. Thus, the aim of this study is to investigate the effects of ATP and benidipine, administered alone and in combination, on bevacizumab-induced renal damage in rats, using biochemical and histopathological techniques.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 30 male albino Wistar rats with a body weight of 250–267 g were used in the experiment. All rats were obtained from the Atatürk University Medical Experimental Practice and Research Center (Erzurum, Turkey). Prior to the experiment, the animals were housed and fed under suitable conditions at normal room temperature (22°C) in a suitable laboratory setting. The protocols and procedures were approved by the local Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (meeting No. 8 on July 28, 2020).

Pharmacological agents

Bevacizumab (100 mg/4 mL) was supplied by Roche Switzerland (Basel, Switzerland), benidipine was supplied by Deva (Istanbul, Turkey), thiopental sodium was supplied by İ.E ULAGAY (Istanbul, Turkey), and ATP was supplied by Zdorove Narodu (Kharkiv, Ukraine).

Experimental groups

Rats were divided into 5 treatment groups: bevacizumab (BVZ) alone, ATP + bevacizumab (ABVZ), benidipine + bevacizumab (BBVZ), ATP + benidipine + bevacizumab (ABBVZ), and healthy controls (HC).

Experimental procedure

Adenosine triphosphate was administered at a dose of 25 mg/kg intraperitoneally (ip.) to the ABVZ group of rats. Benidipine was administered orally by gavage at a dose of 4 mg/kg to the BBVZ group. Adenosine triphosphate (25 mg/kg, ip.) and benidipine (4 mg/kg, orally) were administered simultaneously to the ABBVZ group. Normal saline (0.9% NaCl) was administered to the HC group. One hour after the administration of ATP, benidipine or saline, bevacizumab was injected ip. at a dose of 10 mg/kg to the BVZ, ABVZ, BBVZ, and ABBVZ groups. A total of 2 doses of bevacizumab were delivered with an interval of 15 days. Adenosine triphosphate and benidipine were administered once daily for 1 month. The animals were sacrificed using a high dose of thiopental sodium (50 mg/kg) at the end of this period. The kidneys were removed immediately after the animals were sacrificed. Malondialdehyde (MDA), total glutathione (tGSH) levels, total oxidant status (TOS), and total antioxidant status (TAS) values were measured in the renal tissue. Renal tissue samples were also examined histopathologically. Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were measured in blood samples taken before the animals were sacrificed.

Biochemical analyses

MDA measurement

The MDA measurement was conducted applying the method developed by Ohkawa et al.14 Briefly, 25 µL of sodium dodecyl sulfate (80 g/L) and 1 mL of a mixture of 200 g/L acetic acid and 1.5 mL 8 g/L 2-thiobarbituric acid were added to 25 µL of the sample and heated at 95°C for 60 min. After cooling down, the samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance of the upper layer was then measured at 532 nm. The amount of MDA in the sample was calculated on a calibration graph drawn using 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane as a standard.

tGSH measurement

The method of Sedlak et al. was applied for tGSH analysis.15 For deproteinization, the samples were processed with metaphosphoric acid in a ratio of 1:1 and centrifuged accordingly. Briefly, 150 µL of measurement mixture (5.85 mL of 100 mM Na-phosphate buffer, 2.8 mL of 1 mM 5,5-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), 3.75 mL of 1 mM nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and 80 µL of 625 U/L glutathione reductase) was added to 50 µL of the supernatant acquired from the sample. Measurements were conducted at 412 nm according to a standard graph prepared with oxidized

glutathione (GSSG).

Measurements of TOS and TAS

The TOS and TAS levels of tissue homogenates were determined using a novel automated measurement method and commercially available kits (Rel Assay Diagnostics, Gaziantep, Turkey), both developed by Erel.16, 17 The TAS method is based on bleaching of the characteristic color of a more stable 2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical cation with antioxidants and measurements performed at 660 nm. The results are expressed as nmol hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) equivalent/L. For the TOS method, the oxidants present in the sample oxidize the ferrous ion-o-dianisidine complex to ferric ion. The oxidation reaction is enhanced by glycerol molecules, which are abundantly present in the reaction medium. The ferric ion produces a colored complex with xylenol orange in an acidic medium. The color intensity, which was measured at 530 nm spectrophotometrically, is related to the total amount of oxidant molecules present in the sample. The results are expressed as µmol Trolox equivalent/L. The percentage ratio of TOS to TAS was used as the oxidative stress index (OSI). The OSI was calculated as TOS divided by 100 × TAS.

Creatinine measurement

The quantitative assay for serum creatinine was conducted with spectrophotometric analysis using a Roche Cobas 8000 autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). This kinetic colorimetric test was performed based on the Jaffe method. A yellow-orange color complex was formed with the creatinine picrate in alkaline solution. This complex was measured at a wavelength of 505 nm. The rate of stain formation is proportional to the creatinine concentration found in the sample. “Rate-blanking” (rate shield) was used to minimize the bilirubin interference. For the purposes of correcting the nonspecific reaction caused by serum/plasma pseudo-creatinine chromogens, including proteins and ketones, serum or plasma outcomes were corrected with −26 μmol/mL (−0.3 mg/dL).

BUN measurement

The quantitative assay for serum urea levels was also conducted with the spectrophotometric method using a Roche Cobas 8000 autoanalyzer. The levels were calculated using the formula BUN = urea × 0.48. The kinetic test with urease and glutamate dehydrogenase is based on urea hydrolysis into ammonium and carbonate ions (urea + 2 H2O → (Urease) → 2 NH4+ + CO32–). In the 2nd reaction, L-glutamate is formed when 2-oxoglutarate reacts with ammonium in the presence of glutamate and dehydrogenase (GLDH) and coenzyme NADH in the medium (NH4+ + 2-oxoglutarate + NADH → (GLDH) → L-glutamate + NAD+ + H2O NADH). In this reaction, 2 moles of NADH are oxidized to NAD+ for every mole of urea hydrolyzed. The rate of decrease in the concentration is directly proportional to the urea concentration in the sample. The measurement was conducted at a wavelength of 340 nm.

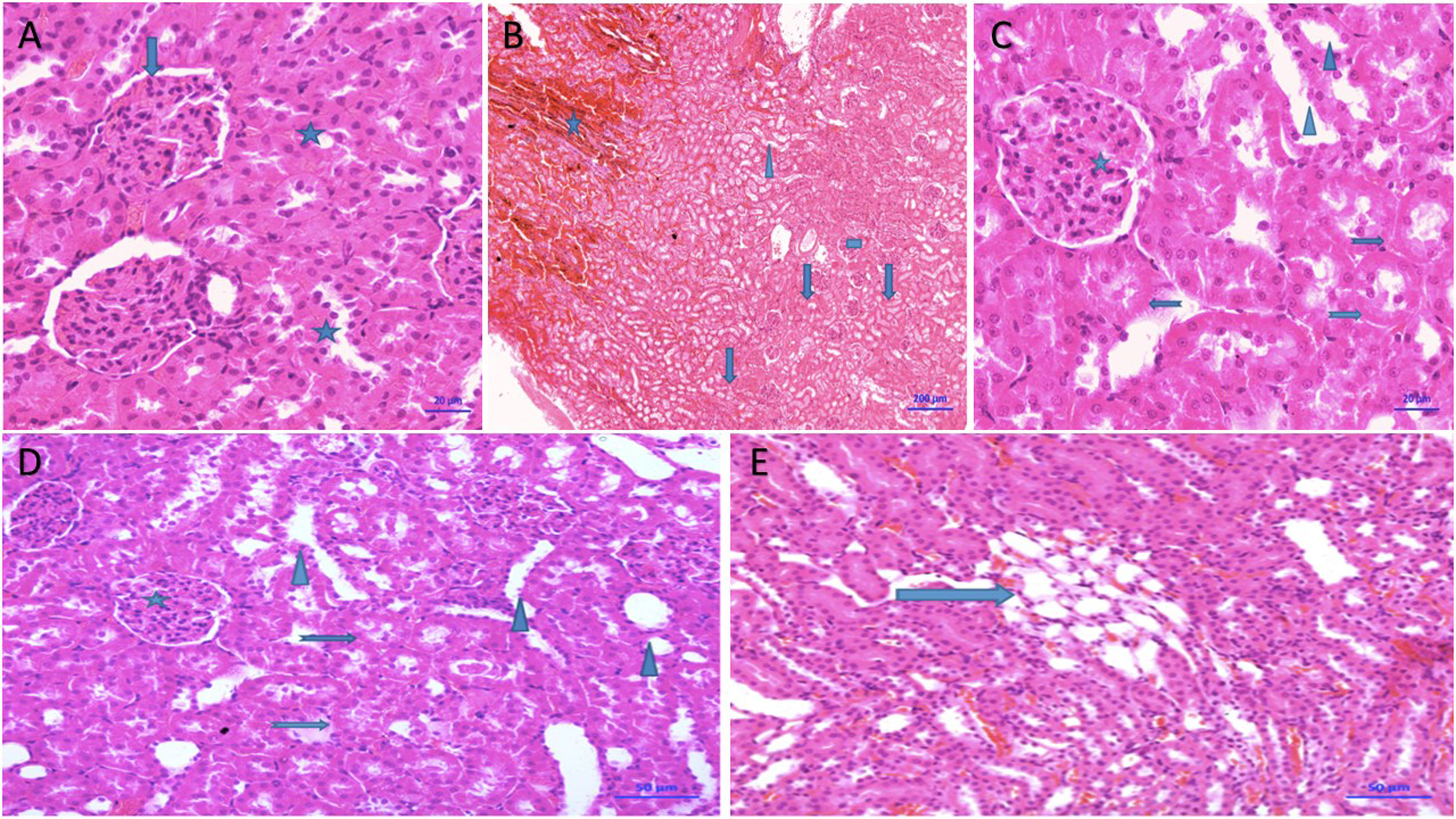

Histopathological analyses

Renal tissues were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin for a period of at least 24 h. The tissues were then embedded in paraffin blocks and sliced horizontally using a microtome into 4-μm sections. A minimum of 3 sections were obtained from each sample and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histomorphological assessment. The stained sections were assessed by an independent pathologist (who was blinded to the experimental treatments) using an AXIO LAB A1 Zeiss microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany). The severity of the histopathological findings in each section was scored between 0 and 3. The assignment of the severity grades was as follows: 0 – normal tissue; 1 – mild damage; 2 – moderate damage; and 3 – severe damage.

Statistical analyses

The biochemical results are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). With the exception of the MDA results, the significance of the differences between groups was tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For the MDA analysis, a Kruskal–Wallis test was performed. Tukey’s tests were used for post hoc comparisons, except for TOS. For TOS, the homogeneity of variances assumption was not met and the Games–Howell test was used.

The values obtained with histopathological grading are expressed as median and the difference between groups was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with the Dunn’s test used for post hoc comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows v. 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA), and a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Biochemical findings

MDA and tGSH analyses

As seen in Figure 1, the amount of MDA in the kidney tissue of the animals was different across study groups (Kruskal–Wallis H: 26.99, p < 0.001, Table 1). The MDA levels in the BVZ group increased significantly compared to the HC group (p < 0.001), ABVZ (p < 0.001), BBVZ (p < 0.001), and the ABBVZ groups (p < 0.001). The amount of MDA in the kidney tissue of the ABVZ group was found to be lower than in the BBVZ group (p < 0.001). The MDA level was also found to be the lowest in the ABBVZ group. The difference in MDA levels between the ABBVZ group and the HC group was statistically insignificant (p = 0.471).

Bevacizumab administration also caused a decrease in tGSH in kidney tissue (F(4,25) = 521.8, p < 0.001; Figure 2, Table 1). The level of tGSH decreased more significantly in the ABVZ group according to the BBVZ group. The tGSH levels of the ABBVZ group were the closest to that of the HC group (but still statistically different, p = 0.024). The combination of ATP + benidipine was the best at preventing the reduction of tGSH.

TOS and TAS analyses

The TOS and TAS levels were found to be significantly different across the study groups (F(4,25) = 783.1, p < 0.001; F(4,25) = 583.9, p < 0.001, respectively; Table 1). As can be seen in Figure 3 and Figure 4, while bevacizumab increased the TOS levels (p < 0.001) in the kidney tissue of the animals, it decreased the TAS levels (p < 0.001). The drugs with the best efficacy for preventing increased TOS were in the ABBVZ (p < 0.001), ABVZ (p < 0.001) and BBVZ groups (p < 0.001), respectively. Likewise, the drugs with the best efficacy for preventing decreased TAS were in the ABBVZ, ABVZ and BBVZ groups, respectively. The group with the TOS and TAS values closest to the HC group was compared with the ABBVZ group (p = 0.266, p = 0.104, respectively).

Creatinine and BUN analyses

Creatinine and BUN levels were also found to be significantly different across groups (F(4,25) = 105.8, p < 0.001; F(4,25) = 724.5, p < 0.001, respectively; Table 1). Compared to the other groups, creatinine and BUN levels in the blood serum samples of the animal group treated with bevacizumab demonstrated a significant increase (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively; Figure 5 and Figure 6). The administration of ATP significantly decreased the bevacizumab-related increase in creatinine and BUN levels (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). The increase in creatinine and BUN levels was also significantly decreased in the BBVZ group (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). However, the differences in creatinine and BUN levels were statistically significant in favor of the ABVZ group, compared to the BBVZ group (p = 0.005, p < 0.001, respectively). The combination of ATP + benidipine was found to be the best for prevention of the increased creatinine and BUN levels. Also, the differences in creatinine and BUN levels between the ABBVZ and HC groups were statistically insignificant (p = 0.966, p = 0.515, respectively).

Histopathological findings

Figure 7A shows that no pathological findings were observed in the renal tissue of the HC group. Also, no histopathological damage was detected in the glomeruli of any animal group. However, grade 3 hemorrhage, tubular necrosis and focal tubular atrophy were observed in the kidneys of animals from the BVZ group (Figure 7B, Table 2). While grade 1 atrophic tubular structures and focal single cell necrosis were observed in the ABVZ group (Figure 7C, Table 2), the damage to these structures in the BBVZ group was evaluated as grade 2 (Figure 7D, Table 2). No pathological findings, except grade 1 atrophic tubules, were observed in the kidneys of the ABBVZ group (Figure 7E, Table 2).

Discussion

This study focused on the effects of ATP, benidipine and the combination of ATP and benidipine on possible rat renal damage induced with bevacizumab, using biochemical and histopathological methods. The biochemical examinations revealed increased levels of oxidant parameters such as MDA and TOS in the renal tissue of animals treated with bevacizumab, while the levels of antioxidant parameters such as tGSH and TAS were decreased significantly.

Malondialdehyde is a toxic product released by ROS as a result of the peroxidation of cell membrane lipids.18 Malondialdehyde cross-binds to membrane components and initiates a polymerization reaction that causes serious damage to membrane receptors and proteins.19 Glutathione (GSH), unlike MDA, is an endogenous antioxidant molecule neutralizing ROS.20

The TOS and TAS are substantial markers used in identifying the total oxidant and antioxidant capacity.16, 17 Oxidative stress intensity increases TOS levels and decreases TAS levels. The physiological balance between oxidant and antioxidant changing in favor of oxidants is regarded as oxidative stress.21 In the BVZ group, animals showed increased TOS and MDA levels, and decreased TAS and tGSH levels, suggesting that bevacizumab induced oxidative stress. Moreover, oxidative stress is defined as the excessive production of ROS that cannot be prevented by the effects of antioxidants and the disruption of cell redox equilibrium.22 The results of the current experiment, in combination with previous data, suggest that bevacizumab results in oxidative stress in the renal tissue. However, no data are available in the literature to directly show that bevacizumab induced the oxidative damage.

In the blood samples, it was observed that bevacizumab administration significantly increased creatinine and BUN levels. Increased creatinine and BUN levels in the BVZ group indicate that oxidative damage developed in the kidneys. Many studies report that oxidative stress can impair renal functions and antioxidant administration is beneficial in the treatment of oxidative renal damage.23, 24 In a recently conducted study, serum creatinine and BUN were utilized to assess oxidative renal impairment and an increase in these parameters was associated with oxidative damage.25 Studies have also shown that increased creatinine and BUN levels are due to permanent damage to the renal tubules.26

In the current study, it was also determined that ATP alleviated the bevacizumab-induced rat kidney damage by preventing oxidative stress. These results suggest that inhibition of a chain reaction involving decreased VEGF and ATP, Na+/K+-ATPase pump inhibition, increased intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations, and the triggering of ROS production, respectively, may have resulted from bevacizumab administration. Previous studies have suggested that ATP promotes epithelialization by increasing VEGF levels.11 A recent study by Yıldırım et al. also reports that ATP heals oxidative dermal damage induced by sunitinib, a target-driven anticancer drug.27 It has also been found that VEGF inhibition is accountable for the oxidative heart and dermal damage associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (target-driven anticancer drugs), and that this damage was minimized by the administration of ATP.28, 29

The current biochemical and histopathological results show that the oxidative renal damage associated with bevacizumab is also suppressed by benidipine. As stated above, benidipine is a Ca2+ channel blocker drug with antioxidant properties.12, 13 This pharmacological agent has a strong effect and long duration of action with a high affinity for calcium channels.30 Benidipine is not only known to inhibit L-type Ca2+ channels, but also N- and T-type Ca2+ channels,31 and the nephroprotective effect of benidipine is presumed to be due to the blockade of these 3 channels.30 It has also been reported that benidipine suppresses the increase of serum creatinine, lipid peroxidation and intracellular calcium levels due to renal ischemia, while preventing a decrease in renal ATP.32 Thus, the possible mechanisms by which benidipine prevents bevacizumab-induced oxidative kidney damage are likely due to its antioxidant properties, inhibitory effects on ATP depletion, and its Ca2+ channel blocking effects.

It has also been shown that increased intracellular Ca2+ levels are associated with ROS production and cell damage.8, 9 However, benidipine suppressed bevacizumab-associated kidney damage less than ATP, suggesting that the effects of benidipine may be primarily due to its inhibitory effect on VEGF production. Indeed, Jesmin et al. have reported that benidipine inhibits the excessive production of VEGF.33 Considering the mechanism of action of bevacizumab,1 these findings support our original hypothesis that ATP, benidipine, and especially ATP combined with benidipine, may be effective against bevacizumab toxicity. In the current study, the treatments that reduced bevacizumab-associated oxidative kidney damage most effectively were the ATP and benidipine combination, ATP and benidipine, in descending order.

In the present study, histopathological signs of damage, such as severe necrosis, atrophy and hemorrhage, were observed in the renal tubules of the BVZ group. However, there was no damage to the glomeruli. Similarly, Assayag et al. found that tubular necrosis developed in a patient who was administered bevacizumab. However, since bevacizumab was used in combination with other chemotherapeutic drugs, it could not be conclusively determined that this damage was related to bevacizumab.34 Another study also reported tubular necrosis in patients treated with bevacizumab and VEGF inhibitors.35 Zhao et al., using light microscopy, could not determine if bevacizumab caused morphological damage to the glomeruli. However, a subsequent electron microscopy analysis demonstrated that the glomeruli experienced certain morphological changes following bevacizumab administration.36

Limitations

In future studies, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels should also be investigated to clarify the protective effects of the combination of ATP and benidipine on bevacizumab toxicity.

Conclusions

The administration of bevacizumab resulted in tubular necrosis with oxidative stress in the renal tissue of animals. Benidipine significantly reduced the damage associated with bevacizumab, and ATP reduced it even more significantly. However, a combination of ATP and benidipine was the most effective in reducing bevacizumab-associated oxidative stress and tubular damage. Thus, the results of our trial revealed that ATP and benidipine reduce bevacizumab-related renal toxicity. However, the combination of ATP and benidipine is suggested to be a potential therapeutic strategy for the prevention of bevacizumab toxicity.