Abstract

The assessment of functional severity of moderate coronary stenoses is challenging. Coronary angiography remains the standard technique for diagnosis, although, due to its limitations, it is frequently insufficient to detect relevant myocardial ischemia. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) is defined as the ratio between the mean hyperemic coronary artery pressure distal to the lesion and mean pressure in the aorta. The FFR measurement is currently supported by guidelines to evaluate the hemodynamic significance of lesions. Proper identification of patients that have the potential to benefit from revascularization is crucial. Based on already published literature, we focus on the long-term follow-up of patients with FFR-driven treatment. We also provide a review of specific clinical cases such as borderline FFR values, comorbidities or lesions in anatomical risk locations, in which interpretation can be challenging during the physiological assessment. The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of the evidence of FFR implementation in daily clinical practice and determine issues that raise doubts.

Key words: revascularization, medical therapy, coronary artery disease (CAD), fractional flow reserve (FFR), grey zone

Introduction

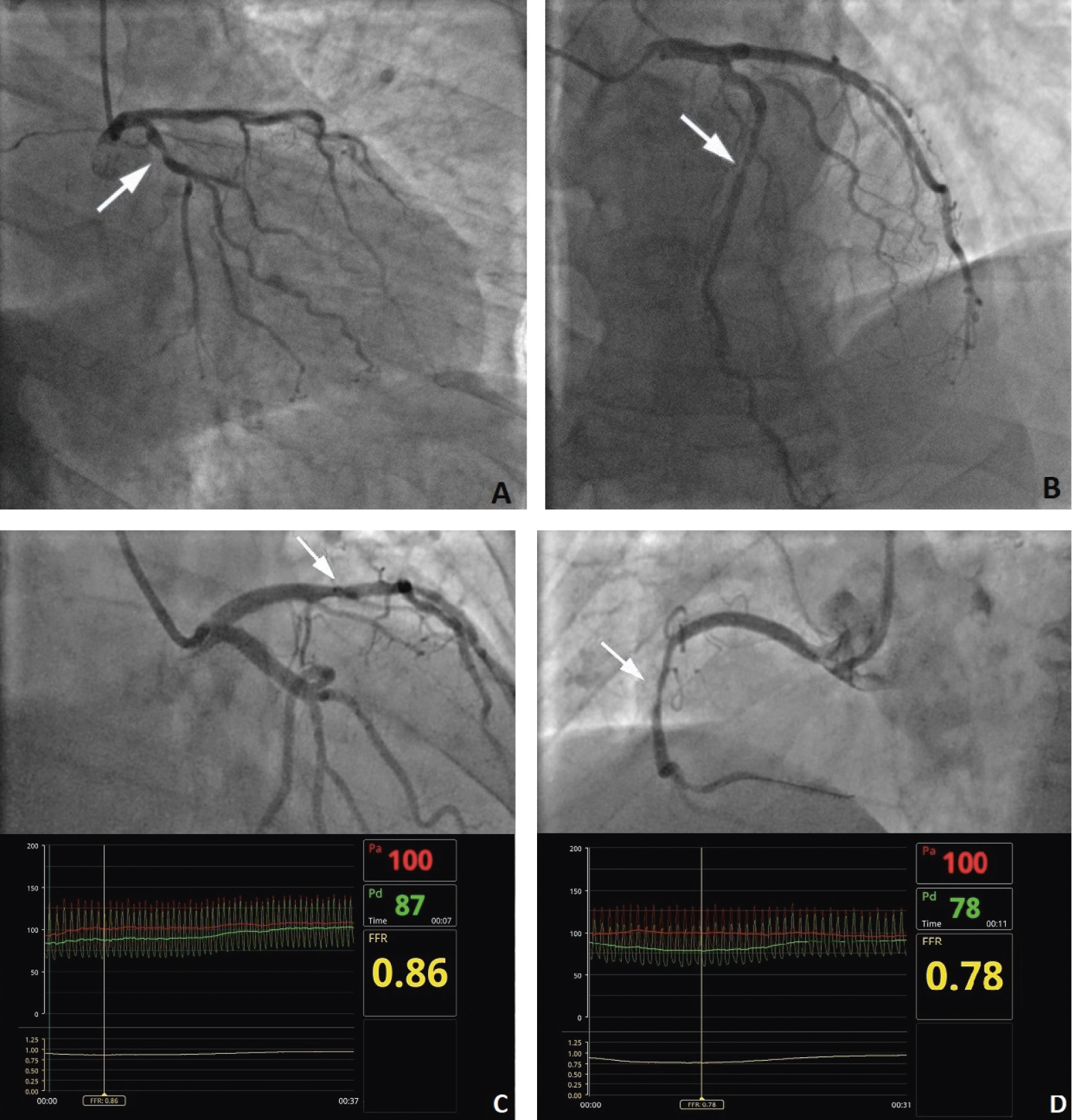

Precise identification of significant stenosis in coronary artery disease (CAD) is of major importance during the treatment and decision-making process. The accuracy of diagnostic procedures enables identification of patients who may benefit from revascularization. In numerous centers, coronary angiography remains the gold standard of diagnostics to select the best therapy, which may include coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or pharmacotherapy.1 Interpretation of stenosis based only on angiography remains challenging due to several limitations, such as contrast streaming, vessel covering, two-dimensional representation of the structures, and difficulties in evaluation of stenosis severity. Previous studies disclosed that intra- and interobserver variability of angiographic interpretation of the presence of significant narrowing ranges from 15% to 45%,2, 3 which presents a risk of unnecessary PCI treatment or inappropriate deferral of revascularization (Figure 1). To improve the decision-making process, current guidelines recommend evaluating coronary pressure-derived fractional flow reserve (FFR) for the hemodynamic assessment of lesions in stable patients.4 As a consequence, FFR has become a valuable modality in catheterization laboratories. Nevertheless, physiological assessment of epicardial coronary stenosis using FFR can also be hampered by its limitations. The FFR is performed in hyperemia to minimize the effects of the coronary microcirculation; thus, it requires the administration of pharmacological agents such as adenosine. Multiple factors such as diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy and severe aortic valve stenosis can disrupt maximal hyperemia and lead to overestimation of the FFR measurement.5 Furthermore, characteristics of lesions such as bifurcation, left main stem disease, serial lesions, or stenosis in ostium can also affect the FFR evaluation.6

The current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend FFR and instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) measurement (both tools with IA class of recommendations) to assess the severity of intermediate-grade lesions in cases where there is no evidence of ischemia in non-invasive tests or in multivessel disease.4 Only FFR is recommended to guide revascularization (IIa B); there is no information about iFR-guided percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). The ESC guidelines for chronic coronary syndromes recommend FFR for cardiovascular risk stratification in symptomatic patients with high-risk profile, and FFR/iFR for patients with mild or no symptoms (both with class IA) in whom revascularization is considered for improvement of prognosis. Moreover, FFR should be considered for risk stratification in patients with conflicting results from noninvasive testing (IIa/B).7 The guidelines indicate the need for randomized trials comparing the iFR-guided treatment strategy of patients with intermediate lesions compared with medical therapy. The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines recommend FFR as a suitable tool to assess intermediate coronary lesions and to guide revascularization decisions in stable ischemic heart disease (IIa A). There is no information about iFR-guided revascularization (Table 1).8

Fractional flow reserve and instantaneous wave-free ratio procedures

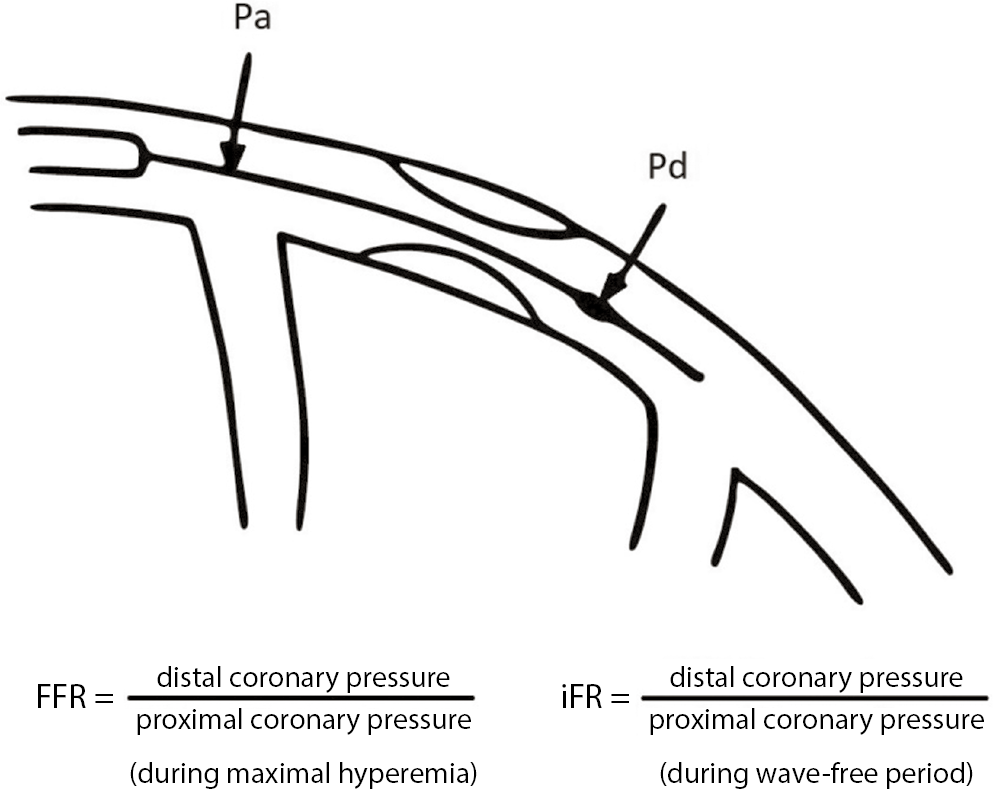

To perform FFR measurements, clinicians utilize a guiding catheter, a pressure guidewire, hyperemic agents, and an interface to display FFR values and curves. A guiding catheter allows rapid use of balloons or stents in the case of complications such as perforation or artery dissection. Radial and femoral access are equally suitable for FFR. Guidewires are available, i.a., from Boston Scientific, Abbott, St. Jude Medical, and Volcano, and a microcatheter is available from Acist (Table 2). The pressure sensor is located 3 cm from the distal tip of an FFR-specific guidewire and on the tip of a microcatheter. The aortic pressure on the interface must be zeroed prior to measurement. Thereafter, a cardiologist administers nitrates (100 μg or 200 μg) to prevent spasms and reduce the resistance in epicardial arteries. The operator then places the pressure wire (or microcatheter) into the guiding catheter and then into the coronary artery. The tip of the guidewire must be positioned precisely 1 mm or 2 mm outside the catheter to equalize the pressure from the guiding catheter and pressure wire. As soon as the equipment is located in coronary arteries, heparin should be administered. In the next step, the operator should insert the guidewire distal to the investigated lesion. Hyperemia is then induced through intracoronary infusion of adenosine (100 µg for the right coronary artery or 200 µg for left coronary artery). These doses produce maximal hyperemia with minimal side effects such as atrioventricular blocks or disorders in heart rate or blood pressure.9 Alternatively, adenosine may be infused through a central vein (140 µg/kg/min). Physiological assessment is also possible without adenosine required: papaverine, nitroprusside or regadenoson may also be used. Regadenoson is particularly recommended for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), where regadenoson decreases the risk of bronchoconstriction.10 Aortic pressure (Pa) is obtained from the guiding catheter and distal pressure (Pd) from the pressure sensor on the wire. At this point, FFR is computed as the proportion of the mean hyperemic distal coronary artery pressure to the mean pressure in the aorta. In physiological conditions, a 1:1 relationship indicates no flow restriction.

Instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) is assessed using the same pressure wire and calculated as the ratio of distal coronary pressure to the aortic pressure (Pd/Pa) (Figure 2). The primary difference between FFR and iFR is that iFR is performed during the isolated period of diastole – the wave-free period – while microvascular resistance is low and stable and does not affect coronary flow.11 The ADVISE-in-practice study reported the correlation between an iFR threshold of 0.9 and FFR threshold of 0.8.12 Meta-analysis of 2 trials, Functional Lesion Assessment of Intermediate Stenosis to Guide Revascularisation (DEFINE-FLAIR) and The Instantaneous Wave-Free Ratio versus Fractional Flow Reserve in Patients with Stable Angina Pectoris or Acute Coronary Syndrome (iFR-SWEDEHEART), reported that iFR-guided management was not inferior to FFR guidance in respect to death, myocardial infarction (MI) and unplanned revascularization.13

Objectives

The aim of the present article is to explore the clinical implementation, accuracy and limitations of FFR measurement. Based on already published literature, we focus on the long-term follow-up of patients with FFR-driven treatment. We also conduct an overview of specific clinical cases, where interpretation can be challenging during the physiological assessment, such as borderline FFR values, comorbidity or lesions in anatomical risk locations. Our review is intended to improve understanding of the diagnostic results and, in consequence, result in more suitable treatment strategies.

Importance of fractional flow reserve measurement

There are 3 pivotal, randomized trials in the area of physiological assessment of coronary lesions severity: FAME 1,14 FAME 215 and DEFER.16 First of them revealed that, in comparison with the standard angiography-guided treatment strategy, FFR-guided therapy is associated with better outcomes such as a significant reduction of death, MI and revascularization cases. Furthermore, the use of FFR reduced the number of unnecessary stent implantations and the amount of contrast agents. The 2nd trial showed that revascularization in patients with FFR values ≤0.80 is superior to medical therapy alone. Over 5 years of follow-up, investigators did not observe significant differences in adverse cardiovascular effects between PCI-treated patients with FFR ≤ 0.80 and those with FFR > 0.80 treated with medical therapy only. The DEFER trial demonstrated that deferment of revascularization with an FFR cutoff >0.75 for patients with intermediate stenosis is safe and is still beneficial for functionally nonsignificant lesions after 15 years of follow-up. The results of a meta-analysis and systematic review of the randomized trials FAME 2,15 DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI17 and Compare-Acute18 were published in 2019.19 The goal of this study was to evaluate the effect of FFR guidance in PCI in comparison with medical therapy. The cohort consisted of patients suffering from stable CAD as well as those after acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who were hemodynamically stable, in whom non-infarct-related lesions were investigated. Cardiac death or MI constituted the primary endpoint. The authors concluded that planning revascularization based on FFR was superior to medical treatment, which was achieved primarily through a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of MI. The trial, conducted by Völz et al., assessed the usefulness of FFR in patients with angina pectoris treated with PCI.20 It showed that, compared with angiography-guided PCI, FFR-guided PCI enhanced long-term outcomes because of lower rate of mortality, stent thrombosis and restenosis. Schampaert et al. investigated a cohort of 2217 patients with ACS and stable CAD, and reported that the treatment plan suggested by FFR diverged from the treatment plan indicated by standard angiography in 1/3 of patients.21 Among participants with ACS, 38% had a modified strategy, and among those with CAD, 32.6% had a modified strategy. The treatment plan based on FFR is associated with a reduction of revascularization frequency. Interestingly, Tanaka et al. conducted a study to estimate how treatment plan adjustment based on FFR influences the medical cost.22 Data were adopted from CVIT-DEFER registry.23 After FFR measurement (with a cutoff of 0.80), 90.1% of patients who were initially assigned to PCI (based on coronary angiography) received medical therapy only. Management strategies guided by FFR allow decreasing medical cost due to the reduction of unnecessary stent implantations despite the risk of revascularization in the deferred group.

FFR and iFR advantages and limitations

Specific features of lesions and clinical factors may affect the accuracy of FFR measurement and lead to false negative or false positive FFR values. The theory of FFR calculation is that the relationship between coronary flow and pressure is linear during maximum hyperemia. Factors such as diabetic microangiopathy, former MI or left ventricular hypertrophy may result in microvascular impairment and, in consequence, reduce maximal hyperemia. If maximal hyperemia is not achieved, the pressure gradient can be underestimated and lead to overestimated FFR values. Features of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), such as extravascular compression or high pressure in the left ventricle, can play a role in diminishing hyperemic flow.24 Another situation which can affect physiological assessment is a tandem lesion. In this case, FFR measurement can be underestimated because of the impact of serial lesions on each other. The proximal pressure to the 2nd lesion is affected by the 1st lesion and the other way around. The distal pressure to the 1st lesion can be skewed by the 2nd lesion. It seems that a pull-back FFR measurement is an accurate method to assess which stenosis should be treated first. Moreover, in this case, iFR pull-back measurement can probably provide a more reliable assessment because, in resting conditions, the interplay between both lesions can have minimal impact.25 The influence of downstream epicardial stenosis on the assessment of the hemodynamic significance of stenosis located in left stem was the matter of debate. However, only severe (FFR ≤ 0.50) and proximally situated lesions can affect the FFR measurement in left main stem.26 Another situation in which FFR measurement can be uncertain is aortic stenosis, which is becoming more common due to the aging of the population (and therefore, a higher rate of aortic stenosis) and increasing availability of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Functional assessment with adenosine infusion in patients with aortic stenosis was proven safe and well-tolerated.27 Aortic stenosis may impact the FFR value by inducing hypertrophy and decreasing vasodilation of the coronary circulation. In consequence, it may mask functionally significant coronary lesions. Pesarini et al. reported that borderline lesions which are insignificant at baseline can become “truly” significant after TAVI.28

The advantages of FFR have been extensively studied and validated in many different clinical conditions such as multivessel disease, ACS, left main lesions, diffuse atherosclerosis, and bifurcations. The great number of studies allow for strong recommendations in current guidelines to support clinicians during treatment. The key advantage of FFR is its prognostic power. There is a continuous relationship between FFR values and clinical outcomes, which are modified by medical therapy or revascularization. Patients with lower FFR values obtain more benefits from revascularization.29 The iFR measurement is the alternative method of physiological assessment. Patients with contraindications to adenosine such as obstructive pulmonary disease or atrioventricular nodal blocks can benefit from this approach. The operator does not have to induce hyperemia, which reduces costs and procedural time. The FFR can be used to confirm borderline iFR values. However, an important limitation of iFR is the small number of studies in different pathological and anatomical conditions. The iFR sensibility for hemodynamic variability (due to active autoregulation mechanisms in non-hyperemic conditions) is a continual matter of debate and needs further research. The prognostic role of iFR in guiding myocardial revascularization also requires additional clarification (Table 3). Thus, all cases with specific features that could lead to artificially altered FFR and iFR values should be interpreted with great caution. All abovementioned scenarios may demand a modified diagnostic approach in order to avoid misinterpretation of hemodynamic relevance.

Treatment strategy in borderline FFR values: the so-called “grey zone”

Appropriate management of patients with FFR values between 0.75 and 0.80 remains a subject of debate. A prior study suggested that FFR values in this grey zone are associated with significant myocardial ischemia, although values in this range are observed in a limited number of patients.30, 31 Johnson et al. demonstrated that beneficial FFR thresholds oscillate around the grey zone range.29 Several previous studies have reported conflicting results between revascularization and medical therapy for coronary stenosis in this population. The DEFER trial showed that medical therapy alone with FFR values ≥0.75 was associated with promising outcomes16 even after 15 years of follow-up.32 However, the previous study reported that deferral of revascularization in that group is associated with higher target vessel failure mainly due to urgent revascularization.33 A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated a significant reduction of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and target vessel revascularization (TVR) after revascularization but did not diminish endpoints, such as all-cause death, cardiac death or MI.34 Interestingly, both FAME trials found that all revascularized lesions with FFR ≤ 0.80 had favorable results.35, 36 Furthermore, in their observational study, Adjedj et al. did not report a significant difference in MACE between deferred and medical therapy groups.37

Two recent studies evaluated which medical approaches are associated with improvements in long-term follow-up in the FFR grey zone. In a prospective, controlled trial, Hennigan et al. recruited 104 patients with angina with FFR values between 0.75 and 0.82 for intermediate lesions and randomized half to optimal medical therapy (OMT) only and half to PCI with OMT.30 The primary endpoint was angina status, which was evaluated with the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ). The parameters were estimated in domains of quality of life, treatment satisfaction, physical limitation, angina stability, and angina frequency. The SAQ was initially completed after the index invasive procedure and again 3 and 12 months later. Additionally, participants underwent stress perfusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the same time, to evaluate the ischemia. At 3 months, the mean changes in the SAQ domains of angina frequency and quality of life were in favor of the PCI group. No significant differences were found regarding angina stability, physical limitation or treatment satisfaction. The MRI at baseline revealed that 11 patients with OMT and 6 patients with PCI had noticeable ischemia in the studied region, and there was no significant variation between groups. In the PCI subgroup, after 3 months, only 3 participants still presented ischemia in the target lesion area. Unfortunately, the authors did not report how many patients with OMT in that time revealed ischemia. The final SAQ obtained after 12 months suggested that PCI treatment is still superior to OMT, but it was no longer statistically significant. However, because of the lack of control group and openness of treatment strategy, a placebo effect may have impacted these findings.

Du et al. designed a study to identify beneficial FFR cutoff values for decision-making and risk assessment in patients with coronary stenosis.38 The study included 903 participants who were initially treated with PCI, after which 1210 de novo lesions were detected and evaluated using FFR and further investigated. The mean clinical observation period lasted 21 months. The primary outcome was target lesion failure (TLF), which was defined as a composite of cardiac death, target lesion MI or target lesion revascularization (TLR). After measurement, 44% of participants underwent revascularization. Initially, all lesions were allocated to 4 FFR value categories: ≤0.75, 0.76–0.80, 0.81–0.85, and ≥0.86. Analysis revealed no differences in TLF frequency between performed and deferred revascularization for lesions in the groups with FFR > 0.80, whereas the incidence of TLF for deferred lesions was higher than revascularized lesions in the groups with FFR < 0.80. Of note, in the grey zone, TLF rate in patients with performed PCI amounted to 0%. Next, to appraise the 0.80 value as a proper cutoff for decision-making management, all lesions were assigned to 3 groups: a low FFR (≤0.80) defer (LFD) group and a high FFR (>0.80) defer (HFD) group, in whom lesions were untreated, and a low FFR (≤0.80) performed (LFR) group, in whom lesions were revascularized. The TLF rate was similar in the LFR and HFD groups, but noticeably lower than in the LFD group. In a further phase, deferred lesions were matched again in 4 FFR groups: ≤0.75, 0.76–0.80, 0.81–0.85, and ≥0.86, which showed a crucial increase in cumulative TLF events from the higher to the lower FFR categories. Lesions in both groups with FFR < 0.80 were associated with a poorer outcome. Moreover, it is hard to ignore the fact that, during the study, incompatibility between revascularization strategy and an FFR value of 0.80 was 17.4%. This especially concerned lesions with FFR values in the range of 0.76–0.80, in which management was determined by the physician. These outcomes reported that an FFR value of 0.80 is a beneficial and safe threshold for decision-making for revascularization. Revascularized lesions with FFR values ≤0.80 (included in the grey zone) were associated with improved clinical outcomes (deferment of revascularization was associated with a four-fold increase in the TLF risk in that group), which is consistent with the results from the recent trial conducted by Hennigan et al.30 Among patients with grey zone FFR values, after PCI, no participant developed TLF, whilst 12 subjects with medical treatment developed TLF. Pharmacotherapy alone for those with FFR > 0.80 was identified as a sufficient and safe strategy.

A subsequent study based on the IRIS-FFR registry investigated lesions with FFR values in the grey zone (0.75–0.80).39 Clinicians identified patients with a de novo native coronary artery stenosis. The MACE was a primary endpoint. The mean follow-up duration was 2.9 years. Patients (n = 1334; 1 lesion per 1 patient) were divided into 2 groups: with deferred revascularization (683 subjects) and with performed PCI (651 subjects). Unfortunately, the authors did not inform about decision-making criteria (symptoms or lesion characteristics) used to assign the patients to perform or defer PCI. The MACE, overall mortality, incidence of death, and spontaneous MI event rate did not vary between the 2 groups (MACE appeared in 8.1% in the deferred group compared to 8.4% in the PCI group). Patients who underwent PCI had a significantly higher risk of target vessel infarction due to a higher likelihood of a periprocedural infarct. On the contrary, in the deferred group, an increase in TVR frequency was noted. The ACS, chronic renal failure and multi-vessel coronary artery disease were independent predictors of MACE in the PCI group, whereas left main or proximal left anterior descending artery lesion and multi-vessel coronary artery disease were independent predictors of MACE in the deferred group. Of note, 3.7% of patients in the PCI group and 5.4% of patients in the deferred group experienced TVR. These results demonstrated that patients with grey zone FFR values treated with PCI did not benefit. However, revascularization could be valuable for specific subgroups, such as those with medically refractory angina.

Follow-up after deferred revascularization based on FFR in specific cases

Despite the number of studies concerning the role of FFR during the decision-making process, many clinical cases still require a careful approach. Proper patient recruitment can be challenging due to the lack of clinical evidence. A recent, multicenter study based on the J-CONFIRM registry investigated outcomes of deferred revascularization (based on FFR measurement) in a group of 1263 patients in whom the large majority of lesions (84.6%) demonstrated FFR > 0.80.40 The primary endpoint was target vessel failure (TVF), which consists of cardiac death, target vessel-related MI or clinically-driven TVR. The study revealed that, after 2 years of observation, TVF occurred in 5.5% of deferred lesions, which was mainly driven by a high rate of TVR. The results demonstrated that the FFR value, left main coronary artery (LMCA) lesion, moderately to severely calcified lesion, hemodialysis, and right coronary artery lesion were independent predictors of TVF. This and prior investigations have demonstrated a relationship between increasing rates of TVF and decreasing FFR values. The association between TVF and FFR was observed in the proximal location of coronary stenosis but was not found in the distal segment. These findings also support the conclusion of the study conducted by Adjedj et al.,37 which showed that lower FFR values in the proximal area are associated with higher cardiac event risk and highlighted the hemodynamic importance of stenosis in that region. Therefore, this paper supports the previous findings about the safety of revascularization deferral based on FFR and emphasizes that the aforementioned cases require a cautious approach.

The FACE study (Safety of FFR-guided Revascularisation Deferral in Anatomically Prognostic Disease) was performed to evaluate outcomes of patients with anatomical risk location lesions after deferment of revascularization.41 Clinicians recruited 292 patients with negative FFR (>0.80) and intermediate stenosis as follows: in the left main stem or in the proximal anterior descending artery or with 2 or 3 vessel disease and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 40% or these with lesions in a single remaining patent coronary artery. The primary composite end-point MACE (consisting of death or acute MI) and unplanned TLR were recorded during 18 months of the follow-up. Over this observation time, MACE occurred in 11.6% of patients, death occurred in 3.8% (1.8% due to cardiovascular causes), and 6% required TVR. Event-free survival at follow-up was 88.5%. Chronic kidney disease and ostial stenosis were found as predictors of MACE, but only impaired renal function was revealed as a significant predictor of TLR. The FREAK registry reported a higher rate of false negative FFR values in patients with impaired renal function, which may explain the higher rate of endpoints in this group.42 With regard to ostial lesions, the results are equivocal on the grounds of problems in the interpretation of FFR values in this setting. The presence of the guiding catheter in the coronary ostium can generate artificial stenosis and lead to an overestimation of these lesions. The majority of subjects had proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) lesions, and in this subgroup, the event rate of MACE was 8.3% and it was lower than the overall event rates. This outcome is in line with the previous study, which favors conservative treatment in LAD lesions with negative FFR.43 The results also demonstrated that MACE appeared more often in patients with LMCA disease (6.4% at 1 year and 30.3% at 2 years, mainly comprised of acute MI and TLR). Although these findings are crucial, the major limitation of this outcome is the relatively low statistical representation of the patients with lesions in the LMCA. The authors concluded that FFR-guided revascularization deferral in those settings is safe. However, it must be analyzed carefully, and in certain cases, such as left main stem disease, ostial disease and renal dysfunction, isolated FFR measurement is probably insufficient for risk evaluation.

Sex-specific issues related to ischemic heart disease are a matter of current discussion regarding the appropriateness of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for men and women. Sex differences include pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of CAD.44 Due to limited information on sex-based differences in long-term outcomes after FFR-guided revascularization deferral in patients with stable CAD, Hoshino et al. conducted a study based on 3 registries.45 Each registry included patients undergoing FFR measurement in addition to coronary flow reserve (CFR) and microcirculatory resistance (IMR). Eight hundred seventy-nine participants with FFR > 0.75 who had been deferred from revascularization were observed for 5 years. The patient-oriented composite outcome (POCO; composite of any death, any MI and any revascularization) was a primary endpoint. After 5 years of follow-up, POCO was noted in 83 patients (16 cardiac deaths, 14 MIs and 48 any revascularization) and the POCO rate in women compared to men was 4.8% compared to 11.1%. Women showed higher FFR values than men for non-obstructive lesions, and women have a significantly lower risk of POCO. Furthermore, in comparison with previous records46, 47 where cardiac events were reported in about 10% of women after PCI, the present study revealed that POCO was reported in only 4.9% of women in deferred arms throughout the time of observation. Interestingly, CFR, but not FFR, was a significant predictor of POCO. The CFR values were significantly lower in women. Furthermore, no significant difference in IMR was found between women and men. Analysis displayed that age, diabetes mellitus in men and multivessel disease in women were significant predictors of POCO. This study showed also that there is no variation in cumulative rates of POCO between sexes at the first 3 years of follow-up, which supports the previous results from the FAME study,48 but the rates of POCO were higher for men than for women following the 4th year of the observation period. However, the better prognosis in favor of women can be explained by the smaller number of LAD lesions and the fact that, in this study, no difference in microvascular responsiveness to hyperemic induction between sexes was shown, whereas women have more tendency to suffer from microvascular angina.49 The fact that there are noticeable variations in FFR values between sexes in similar angiographic lesions highlights the significance of physiological assessment of CAD, especially in women, who have a lower probability to develop obstructive epicardial disease as compared with men. The authors suggest that their data indicate the possible necessity of a sex-specific diagnostic approach which considers the pathophysiological differences with sex-differentiated FFR cutoff points.

Using the large, multicenter PRIME-FFR registry (n = 1983), clinicians evaluated the utility of FFR among patients with diabetes (in comparison with those without diabetes) and described the rate of changes in treatment strategy after FFR evaluation. The rate of revascularization deferral and MACE incidence at 1 year follow-up was also assessed.50 Preliminarily, all participants underwent coronary angiography, which was the basis for determining the primary treatment strategy. Afterward, FFR assessment was conducted. Reclassification was recognized when the treatment strategy (pharmacotherapy/PCI/CABG) after FFR measurement was different than the initial one. In this study, patients with diabetes reported lower FFR values than those without diabetes, which is in line with former papers.51, 52 Changes in the treatment approach occurred more frequently in the group with diabetes (41.2%), but were still similar to that in the group without diabetes (37.5%); however, diabetes was associated with more common reclassification from medical therapy to PCI or CABG. One year of observation disclosed that, in patients with diabetes, the rate of MACE between reclassified and non-reclassified groups was similar. Likewise, the rate of MACE after revascularization deferment (based on FFR) between those with and without diabetes was comparable. The exploration indicates that FFR-guided treatment (with 0.80 thresholds) in patients with diabetes improves prognosis. Moreover, revascularization deferral for those patients is safe, despite higher diabetes-related atherosclerotic burden.

Conclusions and future directions

In summary, FFR measurement in patients with stable CAD is a safe and valuable modality to assess the hemodynamic relevance of coronary stenoses. Thus, greater adoption of FFR evaluation can identify patients who benefit from PCI and avoid periprocedural complications of unnecessary revascularization. However, this invasive tool is not free from limitations, and particular lesions features can lead to FFR over- or underestimation. Further studies are needed to investigate lesions with anatomical risk location due to prognostic value, such as left main stem disease or ostial stenosis. Consequently, there is a need to specify clinical factors which can be associated with adverse cardiac events. Further evaluation is required for patients with treatment strategy reclassification after FFR measurement. Long-term observation of patients with angiographic high-grade stenoses which were deferred from revascularization is also needed. Another issue that seems to be valuable during treatment is post-PCI evaluation of FFR. It is not uncommon that, after successful PCI, the treated artery does not achieve satisfactory FFR values. The FFR measurement after revascularization seems to have prognostic significance for MACE. Further studies are needed to evaluate the role of post-PCI FFR and to verify cutoff values for post-procedural FFR. In patients with grey zone FFR values, decision-making is always challenging. Several studies indicated that there is no relevant treatment for all patients with grey zone FFR. Every case judgment should take into account comorbidity, the character of symptoms, lesion complexity, the feasibility of safe stenting, results of non-invasive tests, and patient preference. Factors such as lesions located in the proximal LAD or in the left main stem, refractory angina, or focal gradient favor revascularization, whereas distal lesions, mild symptoms and diffuse gradient suggest conservative treatment. Therefore, there is still room for observational studies and especially for randomized trials to elucidate the most suitable therapeutic plan in this subset of patients.