Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) applications have significantly improved our everyday quality of life. The last decade has witnessed the emergence of up-and-coming applications in the field of dentistry. It is hopeful that AI, especially machine learning (ML), due to its powerful capacity for image processing and decision support systems, will find extensive application in orthodontics in the future. We performed a comprehensive literature review of the latest studies on the application of ML in orthodontic procedures, including diagnosis, decision-making and treatment. Machine learning models have been found to perform similar to or with even higher accuracy than humans in landmark identification, skeletal classification, bone age prediction, and tooth segmentation. Meanwhile, compared to human experts, ML algorithms allow for high agreement and stability in orthodontic decision-making procedures and treatment effect evaluation. However, current research on ML raises important questions regarding its interpretability and dataset sample reliability. Therefore, more collaboration between orthodontic professionals and technicians is urged to achieve a positive symbiosis between AI and the clinic.

Key words: neural network, orthodontics, machine learning, artificial intelligence (AI), convolutional neural network (CNN)

Introduction

The goal of orthodontic treatment is to restore individual normal occlusion and improve facial attractiveness in patients with malocclusion. Malocclusion is a common disease with high prevalence (up to 56% in the world).1 The diagnosis of malocclusion is made with an accurate measurement of distance, planes and angles according to landmarks of soft and hard tissues using lateral cephalogram and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). Due to high spatial resolution and multi-direction presentation, CBCT can provide more accurate craniometric outcomes than lateral cephalograms.2 However, the definitions of the anatomic landmarks differ among orthodontists, so the outcomes of landmark coordinates and geometrical parameters vary significantly in either method and depend largely on the orthodontists’ experience and the image quality. Moreover, the procedures of malocclusion diagnosis are time-consuming.

Treatment decision analysis plays a pivotal role in orthodontic procedures. For instance, orthodontists are often confronted with the choice between extraction and non-extraction orthodontic treatment. Multiple factors including tooth health, arch width and smile esthetics need to be taken into consideration to achieve an optimal clinical effect.3 Additionally, due to higher risk, the choice of orthodontic-orthognathic combined treatment calls for caution, especially in patients with severe skeletal malocclusion and asymmetric jaw deformity.4 Overall, orthodontic decision-making greatly influences the long-term prognosis, but, due to a lack of consensus on complicated cases, plans can vary among different orthodontists and even different cases treated by the same orthodontists. Thus, effective methods are needed to help human experts improve their treatment planning and reduce the inter-physician variability. Moreover, a standard therapy system could provide clinical instructions for young doctors, particularly as the popularity of personalized orthodontics increases and the need for customized plans increases the complexity of treatment decisions.

With the development of computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM), thermoformed tooth aligners have become a popular choice for adult patients with malocclusion.5 Tooth segmentation from intraoral scanning or CBCT is a pivotal step for computer-aided aligner design.6 Although some mathematical methods, including region-based and feature curve-based segmentation, have been studied in tooth segmentation, the digital image results were not ideal, due to the distorted display of interdental and tooth-gingiva areas as well as curvature noises, which affect the manufacturing accuracy.7 Therefore, tooth segmentation based on artificial intelligence (AI) has become a promising method to acquire high precision.

Objectives

Personalized orthodontic treatment poses challenges for orthodontists in diagnosis, decision-making and treatment. Fortunately, considerable increases in the performance of integrated circuits have allowed AI to contribute substantially to handling images and decision-making due to developments in facial recognition and expert systems. Thus far, AI has performed impressively in many applications in dentistry, especially in periodontology, prosthodontics and endodontics, and the research on AI-based orthodontic treatment is burgeoning.8 In this paper, we present current applications of AI in the field of orthodontics and we attempt to predict some future applications.

Artificial intelligence

The introduction of AI

At the beginning of the 1980s, a computer-aided tool called an “expert system” based on rules was strongly promoted by the Japanese government.9 However, due to an inefficient search and indefinite weight relationships between rules, the system could not meet the actual tasks. The emergence of machine learning (ML) solved the dilemma; it showed improved predictive performance by extracting internal connections among manually input features; such process is known as handcraft feature engineering.10 In the next stage of development, automatic feature engineering based on deep learning technology could replace the process of manual extraction.11 As a branch of ML, deep learning relies on neural networks and it achieved the breakthrough of processing high-dimensional structure data, such as images.

Artificial neural networks are based on a collection of connected units or nodes called artificial neurons, which can mimic the neurons in the biological brain. Each connection is like a synapse in a biological brain, which can transmit signals to neighboring neurons. The signal may propagate from input layer to output layer via several hidden layers. Every layer consists of many neurons which are connected to the neurons of previous layers. The synapses represent weighted parameter (w) and constant (b) values. Deep learning refers to optimizing the weighted parameters automatically by minimizing the errors between output and label input.12 The reduction of loss functions of mini-batch using gradient descent, called stochastic gradient descent (SGD), has been widely applied to train neural networks.13

As an evolution of deep learning, convolutional neural network (CNN) enhanced local feature extraction and reduced sensitivity to changes in the position and size of images. In CNN, the hidden layers were replaced by convolutional layers, pooling layers and fully connected layers.14 In convolutional layers, convolutional kernels with the entire depth of the input images are convoluted with the feature values of source pixels, and the calculated outcomes are projected to destined pixels.15 The kernels slide over the feature maps at certain places, and the parameters of each kernel could be shared within every layer.16 Pooling layers can narrow input volumes and decrease calculation amounts. Common pooling functions include average pooling and max pooling. Fully connected layers are assigned before output layers, and the neurons are connected with all the neurons of preceding layers.17

Four AI-driven tasks in dentistry

The 4 major AI-driven tasks in dentistry are classification, regression, detection, and segmentation. The most well-known task in the AI field is classification. This task means assigning objects or features to pre-specified categories.18 Classification models have been widely studied in diagnosis of oral diseases, such as periodontitis and caries.10 The classification neural network will extract features in hidden layers and map optimal categories according to the likelihood in output layers.19 The common classification algorithms include naïve Bayesian, support vector machine (SVM), decision tree, and artificial neural network (ANN).20 Due to convolution and pooling, CNN can handle high-dimensional data such as high-resolution images.21 For instance, CNN has shown its potential in oral cancer pathologic diagnosis through its handling of shape, color and texture features of nuclei.22

In applications based on AI, the regression analysis is used to estimate the relationships between multiple variables and predict dependent variables based on independent variables.23 In dentistry, researchers transformed the procedure of predicting numerical results into a procedure for determinations. For example, clinical decision support systems based on regression can estimate color change after tooth whitening.8 Additionally, regression methods can be integrated into ML models based on SVM and neural network. The accuracy of deep learning models in predicting oral cancer survival rates was significantly better than that of decision trees and Cox proportional hazards regression models.24

Segmentation and detection are similar tasks in AI, but segmentation mainly aims to define the contours of an object, whereas detection aims to define the position of objects.25 Region-based CNN (R-CNN) is commonly utilized in object detection, and its pipelines include extracting region proposals, computing CNN features and classifying regions.26 The most recent algorithm mainly improves proposed region localization efficiency, such as You Only Look Once (YOLO).27 Moreover, it was discovered that a deep learning network based on YOLO was superior to oral surgeons in detecting odontogenic cysts in diagnostic function.28 Object segmentation required in dentistry is based on pixel-wise segmentation and categorizes each pixel in the region of interest (ROI). Fully convolutional network (FCN) was designed to classify all the pixels using a forward propagation.29 In dentistry, delineation is a typical segmentation task that has been applied in tumor diagnosis and radiotherapy planning. The latest Mask R-CNN framework combines object detection and segmentation process, achieving tooth semantic segmentation.30 In Mask R-CNN, ROI align replaces ROI pooling to avoid misalignment, and adds FCN to segment objects in ROI.31

AI in orthodontics

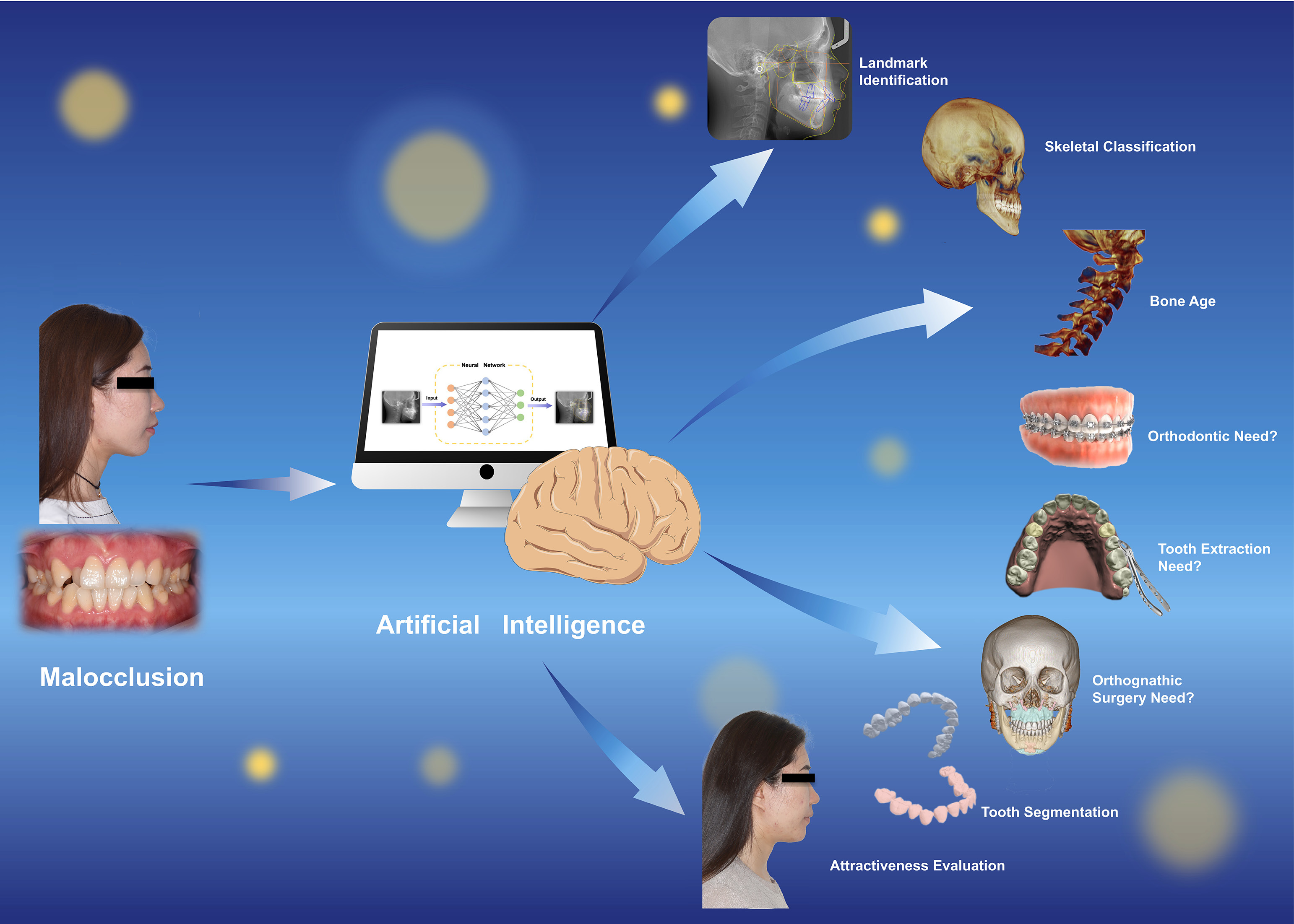

Several reports have indicated that ML has the potential to provide high-quality diagnosis and plan decision-making and treatment in the orthodontic field. Compared to traditional procedures, AI simplifies complex protocols, saves time and provides objective predictable outcomes. The 4 major AI-driven tasks can also be applied to orthodontic treatment. Classification tasks are mainly applied to diagnose skeletal type and predict bone age. Regression tasks are applied to cope with clinical decision-making, such as whether or not to extract teeth. Automatic identification of landmarks belongs to detection tasks, and the acquisition of tooth segmentation belongs to segmentation tasks. This section reviews the current progress of ML in orthodontic diagnosis, decision-making, and treatment, and the specific roles in clinical procedures are vividly represented in Figure 1.

AI-based malocclusion diagnosis

The automatic identification of landmarks

The AI-based diagnostic methods significantly reduce technical sensitivity and improve detection accuracy. The supervised learning model is commonly considered the optimal choice for developing an AI-based cephalometric system, in which training data consist of 2 parts: original images and labels. The original image is a lateral cephalogram or CBCT, and their corresponding labels are the desired X-Y coordinates of landmarks plotted by orthodontists.

Cheng et al. first applied a model based on random forest to detect the odontoid of the epistropheus, which acts as a baseline of the midsagittal plane.32 Although the mean detection error of the model decreased to 3.15 mm, random forest needs to confine the clustered landmarks in the bounding box to avoid searching the whole images. Shahidi et al. utilized feature-based and voxel similarity-based image registration methods to detect 14 landmarks and obtained <3 mm mean absolute error (MAE) for 63.57% of landmarks.33 However, to achieve more accurate registration, severe skeletal deformity and fracture were excluded in the trials. Additionally, Montufar et al. used an active shape model combined with knowledge-based local landmark search to predict 18 landmarks and achieved a higher accuracy with an MAE of 2.51 mm.34 Nevertheless, these methods rely on significant prior knowledge and still require some manual processes. Furthermore, the methods mentioned above cannot apply to test all individuals due to image size, quality and anatomical variations. Moreover, the handcrafted feature-based ML methods depend on specific algorithm templates for different types of malocclusions.

Compared to traditional ML models, CNN-based models became a desirable solution in actual clinical cases. Japanese scholars first applied the CNN model to identify 10 landmarks using 153 lateral cephalograms for model training. However, the precision was restricted by the limited sample volume and measurement bias.35 Kunz et al. expanded the sample to 1792 different cephalograms for training plotted by 12 examiners who were verified by intra-rater and inter-rater reliability calibration.36 The MAE of 11 angles and distances calculated using these coordinates predicted by the CNN model demonstrated no statistically significant differences except for incisor inclination. To improve detection efficiency, an advanced YOLO model, called YOLO v. 3, showed faster detection and higher accuracy in 1028 cephalograms with less than 0.9 mm in the MAE of coordinates when comparing to human.37 Of note, the R-CNN model could detect soft tissue landmarks to provide a reference for evaluating facial profiles. Meanwhile, according to a sensitivity test, the accuracy of the cephalometric system was not hampered by image quality, gender, skeletal classification, or metallic artifacts. However, the detection of the closely-spaced points was a challenge for CNN-based cephalometric systems. The CBCT can provide higher detail resolution than lateral cephalograms. A geodesic map of mandibles was acquired through linear time distance transformation in CBCT.38 A CNN model could only locate the sparsely-spaced points in the geodesic maps and long short-term memory network framework was applied to capture closely spaced distributed landmarks.

Skeletal classification

Besides occlusion, the positions of the jaw relative to the cranium are also a valuable index in pre-orthodontic examination. Different types of skeletal malposition were categorized according to Angle classification. Based on ANB angle and Wits appraisal, the anteroposterior position relationship was classified into 3 types: class I (normal), class II (protrusion) and class III (retrusion). Traditional skeletal classification depends on the manual calculation of linear and angular variables, using craniomaxillary and mandible landmarks. However, mandible positions vary significantly due to occlusion and temporomandibular joint, which causes difficulties in skeletal classification, while craniomaxillary landmarks are relatively stable. The SVM and ANN can predict mandible variables using craniomaxillary variables, and ANN showed higher correlation coefficients than SVM, especially for gnathion (Gn) and menton (Me) points. Remarkably, the independent variables for producing the best prediction outcomes using ANN came from the literature and from SVM selection.39 Besides regression tasks, SVM also generates skeletal classifications based on the automatically extracted craniomaxillary variables. Although the method achieved high sensitivity and precision in predicting class II and III, an unsatisfactory outcome was obtained for class I. This was partially attributed to the misclassification of the cases with marginal values. Better outcomes may be obtained by the combination of synthetic variables and literature variables.40

Compared to handcraft methods, CNN-based skeletal classification has demonstrated better classification performance in terms of accuracy, sensitivity and specificity.41 Instead of utilizing landmarks, the CNN-based method extracts features by first using the located ROI. The CNN-based method can also divide the vertical skeletal class into normal, hyper- and hypodivergent, in addition to the sagittal relationship. Due to superimposition, the classification precision needs further improvement using CBCT images. Moreover, Kim et al. found the CNN-based model with synchronized multi-channels produced ideal outcomes.42 Compared to the single-channel model, better classification performance was achieved by the ensemble and synchronized multi-channel algorithm. However, more influential factors, including race and the wide distribution of normal cases, need to be considered.

AI-based decision-making system

The prediction of bone age

The choice of proper treatment timing depends on bone age prediction based on cervical vertebrae maturity, which indicates the deviation extent from normal growth.43 The prediction methods of bone age depend on low edge concavities and trapezoid taper of vertebral bodies.44 The ML-based methods have shown >90% sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for vertical and sagittal skeletal maturation diagnosis.41 It has been demonstrated that the accuracy of classification models is superior to clustering models in determining cervical vertebral maturation.45 Among a series of classifiers (software), the artificial neural network-based classifier acquired the highest weighted κ coefficient (0.926), whereas the lowest value was obtained by a naïve Bayes classifier (0.861).20, 46 Though lacking accuracy, the discrimination between 2 adjacent stages is not essential to clinical application because the bone development peak occurs between the 3rd and 4th periods.47 If the deviation of adjacent stages is neglected, the accuracy will reach 90.42% using the Bayes classifier.46

Besides cervical vertebral maturation, bone age can also be measured using the ossification centers of the proximal phalanx, metacarpal bone and distal radius when the patients suffer from cervical vertebrae deformity. Gao et al. utilized U-Net to acquire mask images of hand bone, and VGGNet was used to perform image classification tasks.48 The background noise was removed with hand bone segmentation. Of note, the attention module was inserted into the VGGNet to focus on targeted regions and achieved an MAE of 9.997 months. Although the CNN model with attention modules increases accuracy and effectiveness, attention modules would increase complexity and decrease accuracy in the deeper neural networks, such as ResNet and DenseNet.49 Also, due to the additional radiated exposure, manual bone age radiography has been replaced by cervical vertebral maturation assessment using only lateral cephalograms. Therefore, a cervical vertebral maturation degree prediction system based on deep learning requires further research in order to be applied in orthodontic clinical treatment.50

The decision on the need for orthodontic treatment

Traditionally, the decision about whether a patient with malocclusion needs orthodontic treatment is evaluated based on the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (ITON) and Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI).51 The κ values between DAI and ITON in the range of 0.41–0.55 mean that a decision of a specialist is required.51 Tedious and complicated tasks can be replaced by decision-making support systems based on ML. Thanathornwong utilized a Bayesian network to look for underlying connections among 15 features of orthodontic patients and obtained conditional probability distributions.52 When users input the scores for every index, a probability value would be output, determining whether the patients need orthodontic treatment. The results obtained using the semi-automatic system showed high consistency with 2 orthodontists. Nevertheless, manual interpretation of lateral cephalograms intraoral images may create measurement bias. Besides, the decision system should cover patients of a broader age range, especially the mixed dentition period. Estimating the size of the unerupted teeth plays a vital role in judging whether the patients need early intervention treatment during the mixed dentition period. The prediction primarily depends on Moyer’s regression and Tanaka and Johnston’s analysis, but the predicting outcomes are not accurate. Moghimi et al. utilized a hybrid genetic algorithm, (GA)-ANN algorithm, to select reference teeth and find the best mapping function to predict the unerupted teeth sizes.53 A higher proportion of predicting error produced using the GA-ANN algorithm was concentrated at 0 mm and 1 mm, which is acceptable for clinical needs. However, compared to traditional methods used in the treatment of children regardless of different regions and races, future research should improve the generalization capacity of decision systems through high-quality training datasets.

The decision on the need for advance extraction

The controversy over extraction and non-extraction orthodontic treatment remains unsolved. Currently, orthodontic extraction treatment is applied in cases of dental protrusion and crowding and jaw dysplasia.54 Xie et al. described ANN-based decision-making models for determining whether the extraction was necessary.55 Although ANN achieved a 100% success rate in training set using backpropagation, the test outcomes remained at only 80%. Jung et al. chose 1/3 of the training set as a validation set to avoid the overfitting phenomenon.56 The proposed method improved the success rate of ANN and achieved an agreement of 94% with an experienced orthodontist. Additionally, an ANN model consisting of 4 classifiers could not only diagnose the necessity of extraction but also choose proper extraction patterns based on 12 cephalometric variables. Although the accuracy was not ideal in terms of specific extraction positions, only 4 cases were unacceptable for clinical practice. Besides ANN, as one of the ensemble methods, random forest can also prevent overfitting, and random forest showed a lower error rate than ANN regarding the need for extraction and the specific patterns.57 Moreover, bagging or boosting can decrease the error rate of the neural network to prevent overfitting. Interestingly, AI-based models discovered that the primary decisive factors for whether to extract teeth before orthodontic treatment are incompetent lips and lower incisor inclination, which can be used as clinical extraction instructions.55 However, AI models were used only to predict whether extractions are necessary based on cephalometric outcomes and other measurements. Medical imaging can provide more information than manual measurements and improve the accuracy of diagnosis. Thus, studies of AI-based decision-making models should aim to analyze imaging data. For example, Qin et al. proposed a deep learning method of combining fine-grained features from positron emission tomography (PET) with CT images to diagnose lung cancer noninvasively.58 Based on this idea, orthodontists could develop deep learning models for more accurate diagnosis.

The decision on the need for orthognathic surgery

Due to the higher risk of orthognathic surgery, more comprehensive factors must be taken into consideration, including skeletal classification, facial asymmetry and a patient’s chief complaints; all of the above issues bring challenges to clinicians. Therefore, a variety of measurements need to be adopted in the training set to make appropriate decisions. The commonly agreed standard for orthognathic surgery is skeletal class III and asymmetry. Therefore, Knoops et al. utilized an SVM model to diagnose whether patients needed orthognathic surgery using facial scanning images.59 Although the system achieved an accuracy of 95.4%, sample selection bias was used because of the fact that normal dentofacial individuals were chosen as non-surgery patients. Jeong et al. chose 822 facial photographs of patients with dentofacial dysmorphosis and/or malocclusion as training data and adopted 3 measurements: facial asymmetry, protrusion and retrusion.60 The CNN model could extract the profile feature from the front and side facial photographs, and subsequently divided the cases into surgery and non-surgery. To integrate more factors, Choi et al. incorporated more measures such as E-line and occlusal plane into ML models, but the feature values required manual input instead of automatic image extraction.61 The ANN model provided high accuracy during the test stage without overfitting. Besides deciding whether to operate or not, the system can also predict the demand for tooth extraction for surgical patients using 4 classifiers. Obtaining right answers is not the purpose of AI-based models because excessive feature information increases the algorithm complexity and overfitting risk. More importantly, the decision-making system can provide diverse clinical solutions for inexperienced orthodontists.

AI-based orthodontic treatment

The acquisition of tooth segmentation images

Template-based registration has been applied to segment target teeth contours, but the application of the method is limited by image intensity and anatomic similarity.62 Conversely, the level set method can handle the images with anatomic variation, low resolution and noise, but it performs poorly in delineating the edge contours, especially in the interdental areas.63 Kim et al. removed the interdental area with masks and reconstructed the edge contours using Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN).64 Compared to separated scanning without interdental areas, the proposed method improved the precision to 0.004 mm. However, the size of the mask was inversely associated with the accuracy of the reconstruction, due to the masking of adjacent normal structures. Pose regression was found to eliminate the overlapping areas by realigning the volume-of-interest regions.26 Moreover, it was discovered that for tooth segmentation, the pose-aware R-CNN model outperformed the Mask R-CNN model in accuracy and sensitivity.26, 65 Due to redundant region proposals in R-CNN algorithms, similarity matrix and non-maximum suppression can both mine the region proposal network. Cui et al. found similarity matrix to show superiority to non-maximum suppression in segmentation accuracy.65 Additionally, tooth segmentation may often be interfered with by extreme gray values, such as metal artifacts. Chung et al. reported the cutout augmentation method to achieve metal artifacts segmentation.26 Additionally, the edge map combined with original CBCT images enhanced boundary information and caused accuracy improvement.65 With integrity of the spatial relation and shape features, Mask R-CNN was able to achieve tooth instance segmentation.65

The evaluation of treatment effect

Improving facial attractiveness is one of the main reasons for choosing orthodontic treatment. Therefore, it is important for orthodontists to provide patients with an objective and esthetical assessment. Although attractiveness is based in cognitive psychology, ML can act as a useful tool to reflect professional and social esthetic appreciation. The CNN model can simulate humans in grading the attractiveness of facial photographs utilizing facial detection and feature extraction. The outcomes produced by the CNN model were more closely aligned with orthodontists and oral surgeons than laypersons. Meanwhile, the variation resulted in fewer of the same targets. Therefore, these results reflected superior reliability of the CNN-based facial evaluation system. However, the CNN model could not explain the influence of each facial feature on facial attractiveness.66 Zhao et al.utilized ML algorithms to predict facial attractiveness when considering different features, including facial shape, geometric features and triangle area features.67 Importantly, facial shape played a significant role in determining facial attractiveness. The treatment effect differed among different patients due to the treatment planning and individual conditions of a patient, including hairstyle and facial ratio. Moreover, ML can help to evaluate the influence of plastic treatment on patients’ attractiveness. Currently, some scholars found that orthognathic surgery improved facial attractiveness and decreased estimated age by 1.2 years. Significant improvement of facial attractiveness could be seen in patients with facial asymmetry and skeletal class II and III. Additionally, lower jaw osteotomy could most clearly ameliorate facial attractiveness.68 What is important, facial esthetics are influenced by a variety of factors, so we need to reduce the influence of confounding factors such as skin, hairstyle and lighting conditions. Also, as training data, esthetic review bias needs further validation, so global standardized facial databases are recommended.

Limitations and perspectives

The rapid development of AI have contributed to its promising applications in dentistry. Accordingly, a variety of AI-based products have been developed by several companies to assist dental clinical applications such as radiological diagnosis and decision-making, as summarized in Table 1. Due to the advantages of high-dimensional data mining, deep learning models have shown great potential in dentistry, especially in oral oncology. Recently, multi-feature concatenation method has been applied to diagnose cervical lymph node metastasis, enhancing target detection efficiency.69 Additionally, deep convolutional GAN has become an effective solution to predict reconstructive jaw morphology before surgeries, which facilitates accurate 3D printing.70 Breakthroughs in other dental fields can shed light on the application of AI in orthodontics. Despite its potential, many challenges, such as data insufficiency, reproducibility crisis and overfitting need to be solved before AI is implemented into clinical practice.

Data insufficiency

Compared to other medical fields, the high-quality datasets for orthodontic research are limited. The discrepancies in training data make the comparison of different AI-based models questionable. Although supervised learning is currently the optimal choice in malocclusion diagnosis, huge costs and labor required for target labeling create obstacles in creating standardized and high-quality datasets for orthodontic studies, specifically. Additionally, data snooping bias usually occurs because training data are repeatedly applied in the test stage. Therefore, independent datasets for tests should be applied instead of cross-validation. To solve this problem, semi-supervised and weakly supervised learning framework can be used in analyzing many original images, and show comparable accuracy and robustness in diagnosis with supervised learning.71 Moreover, transfer learning and few-shot learning could also become ideal alternatives to solve data insufficiency problems.41

Reproducibility crisis

An increasing number of scientists have realized the reproducibility crisis of AI, which means that many research results cannot be repeated when the same experiment is conducted by another team of scientists. The reasons for this phenomenon include algorithmic and metric knowledge deficiency, as well as misunderstanding. Additionally, many researchers neglect the sensitivity of results to hyper-parameters, including study rate, iteration times and initialization strategy. There are some effective solutions to improve the trustworthiness of AI. For instance, sensitivity tests need to be carried out when evaluating model performance. Furthermore, the improvement of interpretability obtained through visualizing the mechanisms of ML models could aid in solving the dilemma. Of note, data cleaning method can be an effective alternative to prevent manual errors in labeling and measurement from affecting the reproducibility of ML models.

Overfitting problem

Most feature engineering models are confronted with the overfitting problem, i.e., worse performance of the models in predicting unknown samples. Many reasons account for overfitting as, for example, data for testing and training are normally derived from a common internal dataset. Additionally, health data heterogeneity is a key factor. Several improvements can be made to prevent overfitting. Firstly, to improve the external generalization capacities of ML models, greater and more diverse external clinical scenarios are required to validate the performance of the model. Meanwhile, choosing representative datasets needs to be considered. Furthermore, several algorithms have been created to prevent overfitting, such as early stopping, dropout and regularization penalty.72 Multimodal learning can integrate various types of information, including records and images, and reach ideal performance when processing imbalanced data.73

The next step

Besides improving the experimental performance of ML, the question of how to apply AI to revolutionize traditional orthodontic procedures should be considered at present. First of all, due to the black-box feature of ML, enhancing the visualization and establishing patients’ and doctors’ trust should be prioritized before clinical application of ML. Although the interpretability of ML still remains challenging, standardized clinical trials should be conducted, which can serve as strong medical evidence for guidance. During trial design, several methods are needed to control bias risk. For instance, it is essential to conduct inter-rater reliability calibration using consistency validation. Additionally, the allocation schemes should be blind to reviewers to prevent subjective bias. Moreover, providing context-specific empirical validation could also make it easier to audit bias and enhance trust of practitioners, instead of explaining inner workflows.

In the next few years, AI-based orthodontic systems could serve as an auxiliary tool for clinical procedures. The outcomes derived from ML models should be treated cautiously and used as a reference. Additionally, the AI-based models can simulate experts’ ways of thinking and provide the advice for orthodontists. Through ML models, acquisition of theories and practice experiences by young orthodontists could become easier and faster. In addition, with the help of nature language process, ML models could evaluate evidence quality by extracting information from published papers. The evidence evaluation system could relieve residents’ pressure in acquiring medical evidence.

The ethical problems in implementing ML in orthodontic procedures cannot be neglected. Firstly, it is the inherent right of subjects to know about the principles, functions and limitations of the ML models. Secondly, the doctor’s sense of responsibility should be emphasized when establishing cooperation with patients. Thirdly, health data privacy should be redefined due to the prevalence of electronic medical records. Lastly, the legal liability distribution between doctors and ML models should be further improved.

Conclusions

With the advancement of AI in dentistry, high-quality disease diagnosis, decision-making and treatment can be achieved in the near future. However, there are many studies relating to the image recognition, while decision support systems have received little attention. Additionally, clinicians should view AI as a support for diagnosis and treatment, not as a threat. Moreover, clinicians need to be cautious about the prediction outcomes provided by AI models before the interpretability is fully clarified. Due to the growing emphasis on medical responsibility and ethical principles, legal recognition of AI is also a crucial issue. In the future, more clinical trials regarding the application of AI in orthodontics should be carried out to revolutionize traditional orthodontic treatment procedures.