Abstract

Background. The radiofrequency impedance measurement is one of the basic parameters monitored during ablation procedures. An abrupt rise in impedance is often observed corresponding to a steam pop. The exact correlation between the occurrence of steam pop and subsequent rise in impedance has not been experimentally described so far.

Objectives. To evaluate the relationship between steam pop occurrence and impedance fluctuations observed during radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Materials and methods. Porcine heart tissue specimens were appropriately prepared and placed in an experimental setup connected to electrophysiological equipment with 3D anatomical mapping facilities. The RFA lesions were performed in standardized conditions with the use of contact force measurement-enabled open irrigation ablation catheter (ThermoCool SmartTouch™, 3.5 mm tip, F-J curvature; Biosense Webster, Irvine, USA) in the power-control mode. The RFA delivery was stopped when the steam pop occurred. Time taken for the steam pop to occur and to the subsequent abrupt impedance rise was recorded, along with the impedance fluctuations during an application.

Results. In total, 25 experimental radiofrequency (RF) current deliveries ended up with steam pops, which occurred after 30–60 s. The time recorded from the beginning of the application up to the steam pop was shorter if increased power was applied (35 W compared to 30 W: 41.5 ±9.9 s compared to 49.9 ±8.2 s; p = 0.046). During all RF applications, impedance significantly but gradually decreased from 122.9 ±7.9 Ω to 87.5 ±3.6 Ω (p < 0.001) with a mean drop rate of 0.8 ±0.2 Ω/s. During all experiments, the abrupt and significant impedance increase (8.2 ±2.0 Ω, p < 0.001) was observed always after steam pop occurrence (207.4 ±155.9 ms).

Conclusions. During RF current delivery which ended up with steam pop, an abrupt impedance increase was always registered after the occurrence of this phenomenon. Therefore, the impedance rise observed during steam popping cannot be used for its prediction. The time to steam pop was shorter for applications with increased power but not with greater contact force.

Key words: impedance, radiofrequency ablation, tamponade, steam pop, ablation complication

Background

Radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFA) is currently the most common technique used for invasive treatment of a wide variety of arrhythmias. Despite growing understanding of the biophysics of radiofrequency current (RFC) delivery, the procedure is still associated with some degree of risk, and steam pops are one of the most threatening complications.1, 2, 3

Radiofrequency ablation destroys myocardial tissue through thermal injury. Resistive heating occurs in a small zone adjacent to the catheter tip, while the surrounding myocardium is passively heated by conduction. Tissue temperatures above 50°C are necessary to produce irreversible coagulation necrosis. Steam pops result from excessive intramyocardial heating when the temperature exceeds 100°C. In such cases, steam is formed and trapped inside the myocardium. A violent tissue rupture occurs when the steam pressure destroys the structural integrity of the cardiac muscle.4, 5 Steam pops can lead, in the worst cases, to uncontrolled cardiac perforation and the clinical sequelae of cardiac tamponade.6 Steam pop incidence complicating up to 1.5% of RFA procedures has already been a subject of several studies.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Different parameters have been analyzed to predict the occurrence of steam explosions, including classical and novel tools.3, 5, 10, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 An abrupt impedance rise is one of the most widely described physical phenomena accompanying RFA complicated by steam popping.3, 10, 12

Objectives

As it has never been characterized precisely enough, the aim of our in vitro experiment was to evaluate the timing of impedance fluctuations related to steam pop occurrence to establish its predictive potential in such complications.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup

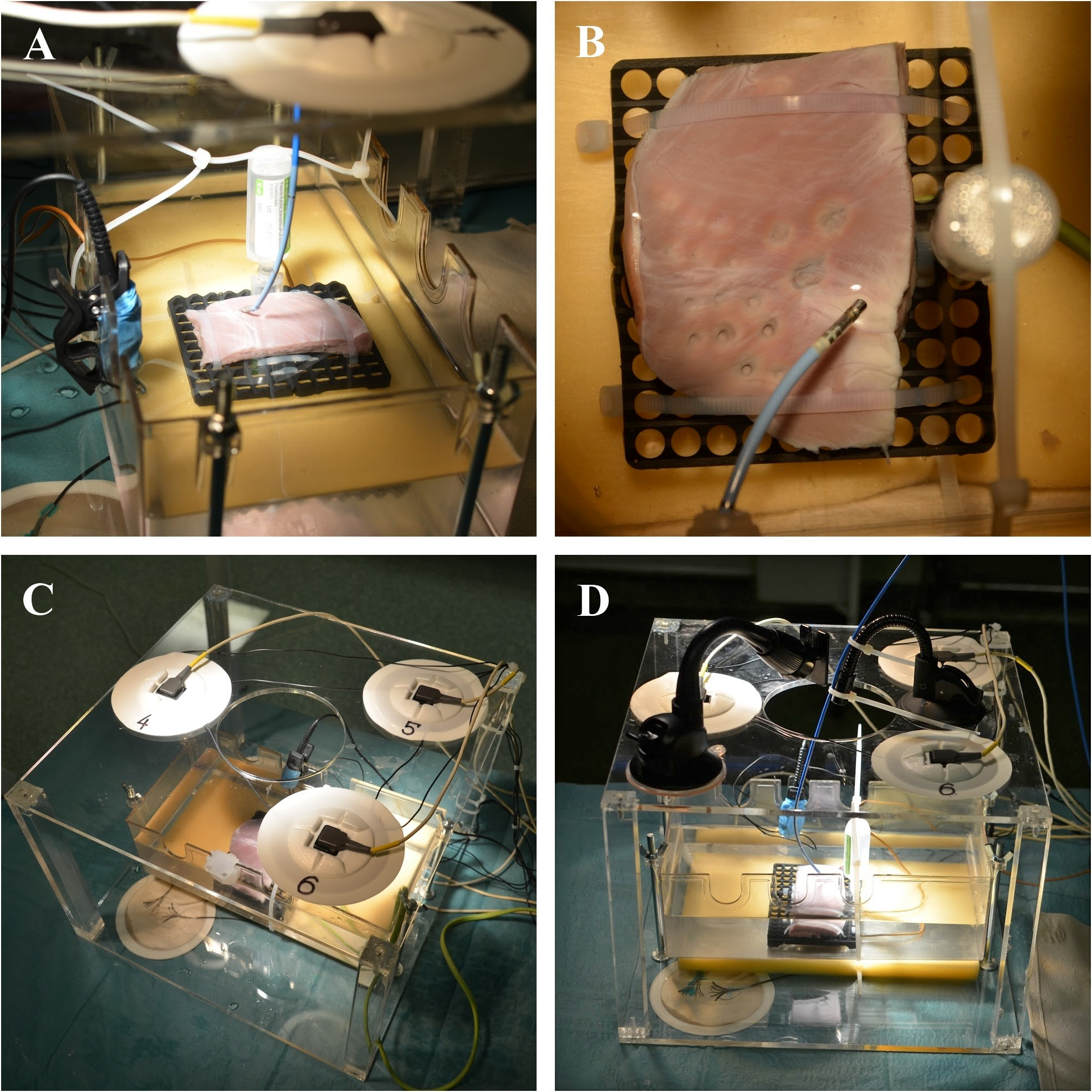

The experimental setup consisted of a transparent container with a sample-holder table and electrical connections necessary to use electrophysiological ablation catheters. Three hearts (weighing 310 g, 340 g and 320 g, respectively) excised by a local abattoir from healthy pigs (Sus scrofa) approx. 6 months of age were used (within 6 h from slaughtering) to prepare 3 separate cuboid samples (dimensions: 70 mm wide, 80 mm long and 15 mm thick). The samples were immersed in saline (0.9% NaCl), which, to approximate physiologic conditions, was heated up to 37 ±2°C and diluted to generate an ablation circuit impedance value within a range of 80–120 Ω. Electrical connections included indifferent RFA electrode located underneath the sample-holding table and connected to radiofrequency (RF) current generator (Stockert 70 RF™ Generator; Stockert GmbH, Freiburg im Brisgau, Germany), electroanatomic reference patches and a reference pad connected to the 3D electroanatomic environment (CARTO™; Biosense Webster Inc., Johnson and Johnson Medical, NV/SA, Waterloo, Belgium). Contact force measurement-enabled open irrigation ablation catheter (ThermoCool SmartTouch™, 3.5 mm tip, F-J curvature; Biosense Webster, Inc., Johnson and Johnson Medical, NV/SA) was used to create ablation lesions. The catheter attachment enabled bidirectional movement of its distal part to achieve the planned target contact force value (Figure 1). Steam pops were identified with a contact microphone (CM200™; Korg, Tokyo, Japan) placed in a saline solution close to the sample table, and connected to the electrophysiological recording system (EP Tracer™; Schwarzer Cardiotek GmbH, Heilbronn, Germany) in a bipolar configuration. Steam pop generated an acoustic wave, which was recorded using an immersed contact microphone and presented as a sharp electrogram by both electrophysiological and electroanatomical systems. The RealGraph™, module of the CARTO™ system, allowed simultaneous presentation of the RFA impedance curve and the spike corresponding to the moment of steam pop occurrence (Figure 2).

Experimental protocol

Before lesion formation, an electroanatomical model of porcine heart tissue specimen was prepared. The RFA was performed in a power-control mode with 2 different energy settings: 30 W and 35 W. These 2 power settings were selected as they were the most commonly used power settings in our centers (35 W was applied for RF applications in the ventricles, the right atrium and non-posterior wall application in the left atrium; 30 W was used in RF applications in the posterior wall of the left atrium). To allow efficient RFC delivery, catheters were irrigated at a flow rate recommended by the manufacturer depending on the ablation power settings: 20 mL/min for the power of 30 W and 30 mL/min for 35 W. Two different contact force levels were maintained, i.e., 20 ±5 g and 30 ±5 g. Continuous measurements of power, impedance and contact force were recorded for each RF ablation. The RFC delivery duration was limited to the steam pop occurrence. The time from the beginning of energy application to the steam pop occurrence, as well as the time to impedance fluctuations were recorded with the accuracy of 1 ms. Additionally, an impedance change was measured as the difference between the maximum impedance after the steam pop and the impedance just before this event. Having determined the power value and the time of application, energy delivered to the tissue was calculated following a standard equation (energy [J] = power [W] × time [s]). The temperature registered on the catheters just before steam pop was also recorded. After each steam pop occurrence, the ablation catheter was moved to another location where the new lesion was created.

As our study was purely experimental, without the participation of any humans nor any living organisms, the investigators waived approval of a bioethical committee. For the same reasons, the Declaration of Helsinki was also not applicable to our research.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica software v. 13 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA). Continuous variables were tested for normality with the Shapiro–Wilk test and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (interquartile range (IQR)). Categorical variables were given as numbers and percentages. When 2 groups were compared, either the Student’s test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used according to the data distribution. Values of p <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 25 experimental RFC deliveries which ended up with steam pops were performed. All the investigated events occurred after approx. 30–60 s (Table 1). The time from the beginning of the application up to the steam pop recording was shorter if increased power value was set (35 W compared to 30 W: 41.5 ±9.9 s compared to 49.9 ±8.2 s; p = 0.046); however, the amount of energy delivered was similar for both subgroups (35 W compared to 30 W: 1453.7 ±346.9 J compared to 1496.2 ±246.3 J; p = 0.7). There was no significant difference in the time to steam pop in applications with distinct contact force (20 g compared to 30 g: 47.7 ±11.3 s compared to 44.3 ±7.5 s; p = 0.4). During all RFC applications, the impedance significantly decreased from 122.9 ±7.9 Ω to 87.5 ±3.6 Ω (p < 0.001), which means a 28.6 ±4.1% reduction of the initial value. This impedance drop did not change significantly regardless of the change in ablation power (30 W compared to 35 W: 36.1 ±6.4 Ω compared to 34.5 ±7.6 Ω; p = 0.64) and the change in contact force values (20 g compared to 30 g: 35.4 ±6.8 Ω compared to 35.4 ±7.1 Ω; p = 1.0). The rate of impedance drop until steam pop amounted to 0.8 ±0.2 Ω/s and did not differ between the applications with lower and increased power (30 W: 0.8 ±0.2 Ω/s compared to 35 W: 0.9 ±0.3 Ω/s; p = 0.2), neither was it different when distinct contact forces were used (20 g: 0.8 ±0.2 Ω/s compared to 30 g: 0.8 ±0.3 Ω/s; p = 0.6). The other parameters did not differ between subgroups.

During all experiments, a significant and abrupt impedance increase (8.2 ±2.0 Ω, p < 0.001) was observed always after steam pop occurrence. The time difference between the steam pop and the rise in the impedance was insignificantly different between RFC applications with 35 W compared to 30 W (180.1 ±113.9 ms compared to 228.9 ±183.8 ms, p = 0.4) as well as those performed with distinct contact force (20 g: 243.9 ±187.7 ms compared to 30 g: 161.6 ±91.3 ms, p = 0.2). Analogously, the impedance rise was comparable in these subgroups (power 35 W: 8.7 ±4.0 Ω compared to 30 W: 7.7 ±2.0 Ω, p = 0.2; contact force 20 g: 7.6 ±2.1 Ω compared to 30 g: 8.9 ±1.8 Ω, p = 0.1). The temperature values recorded just before steam pop occurrence never exceeded 42°C, which proves that irrigation of the catheters was adequate. The results of this experiment are summarized in Table 1.

Discussion

Our study has identified, for the first time, that the abrupt rise in impedance does not precede steam pop but occurs shortly after. Additionally, we revealed that the time for the steam pop to occur was shorter when increased power values were applied, but it was not the case when a greater contact force was used.

Correct prediction of the possibility of a steam pop that can complicate RFA is clinically useful but challenging. During RFC, the energy delivery impedance gradually decreases with tissue heating, and several studies have observed a significant impedance drop before the steam pops. A higher likelihood of steam pops was reported when impedance decreased by more than 15 Ω10, 19, 21; however, this correlation was too vague to either predict or detect steam pops.3, 10 While the magnitude of impedance change during ablation is not a good predictor of steam pops, a rate of impedance drop for ablation lesion exceeding 1 Ω/s is seen as a strong independent predictor of their occurrence.20, 21 However, in our study, the impedance drop rate of 0.8 Ω/s was registered, and yet, in all the experiments, steam pops occurred. This could be accounted for by the difference in the experimental conditions in our in vitro study compared to the in vivo environment. In one of our previous experiments, we reduced the rate of steam pops by using cardiac tissue from porcine hearts just after slaughter (within less than 2 h) along with a high local fluid flow.30 Otherwise, the cardiac tissue might not have had enough potential for energy absorption due to the lack of myocardial perfusion.

An abrupt impedance rise was analyzed in the search for a variable that can predict the occurrence of a steam pop in RFA. In our experiment, all RFC applications were characterized with an impedance rise when steam pops occurred. The precise recording method revealed that the impedance increase did not start before, but shortly after a steam pop-related sound. A potential explanation of this phenomenon may be based on the previously described temperature distribution in the ablated tissue.23, 27, 30 The highest temperature during RFA was recorded up to 3 mm underneath the tissue surface.5, 23, 31 Therefore, the phenomena related to overheating of deeper myocardium are not registered directly on the surface of the endocardium. The impedance rise probably results not only from transformed properties of the cardiac tissue which are provoked by its rupture but also from the catheter movement into an adjacent area. Consequently, the abrupt impedance rise during RFA cannot be used to predict steam pop occurrence. Furthermore, due to the delayed occurrence, any of its derivatives (impedance rise value, impedance rise ratio) cannot be of much use either.

Some authors point out that applications with increased power and greater contact force are connected to an increased probability of steam pops.10, 13, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Our experiments revealed that RFC delivery with the power increased by only 5 W (35 W compared to 30 W) resulted in a shorter time to steam pops. Such findings may indirectly suggest that increased power of RFC applications pose a greater risk of tissue overheating. Contrastingly, we found that the contact force was not related to the time of steam pops occurrence. Our outcomes are inconsistent with other available data21, 22, 23, 24, 25 – most probably due to the relatively minor difference in contact force applied in our experiments (20 g compared to 30 g).

Limitations

The main limitation of our study was the approximation of real-life intracardiac conditions as in vitro settings with the use of porcine cardiac tissue. However, this approach allowed us to control all investigated parameters with high precision.

Conclusions

During the delivery of a RF current delivery which ended up with steam pop, an abrupt impedance increase was registered always after the occurrence of this phenomenon. Therefore, the impedance rise observed during steam popping cannot be used for its prediction. The time to steam pop was shorter for application with increased power but not when greater contact force was applied.