Abstract

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine honored the seminal discovery that regulatory T cells (Tregs) restrain immune responses and prevent autoimmunity through peripheral immune tolerance. However, to obtain a holistic view of peripheral immune tolerance, it is also necessary to consider the role of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) in this process. Therefore, I propose a two-tier model that incorporates both Tregs and MSCs, with Tregs acting within the immune system as an “internal checkpoint” to temper effector cell activity, and tissue-resident MSCs – or “master signaling cells” – serving as an “external checkpoint.” Injury- or pathogen-induced inflammation activates MSCs, which in turn secrete a broad repertoire of immunomodulatory molecules, create a local anti-inflammatory milieu, promote tissue repair, and directly dampen excessive immune activity at the site of damage. The concerted actions of Tregs and MSCs are essential for effective peripheral immune tolerance, shielding the host from pathogens and collateral tissue injury. This model helps explain the pathophysiology of autoimmunity and tumor immune evasion, as well as the therapeutic potential of MSC-based interventions.

Key words: inflammation, immune tolerance, autoimmunity, regulatory T cells, mesenchymal stem/stromal cell

Introduction

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their groundbreaking discovery of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and their role in maintaining immune homeostasis through peripheral immune tolerance.1 Tregs monitor and suppress effector immune cells, preventing excessive immune responses and shielding host tissues from collateral damage.

Recent studies have revealed the widespread presence of another specialized cell population in most organs: mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 These adult stem cells possess potent immunomodulatory capacities and have been shown to directly curb excessive inflammatory responses within tissue niches.8, 9, 10, 11

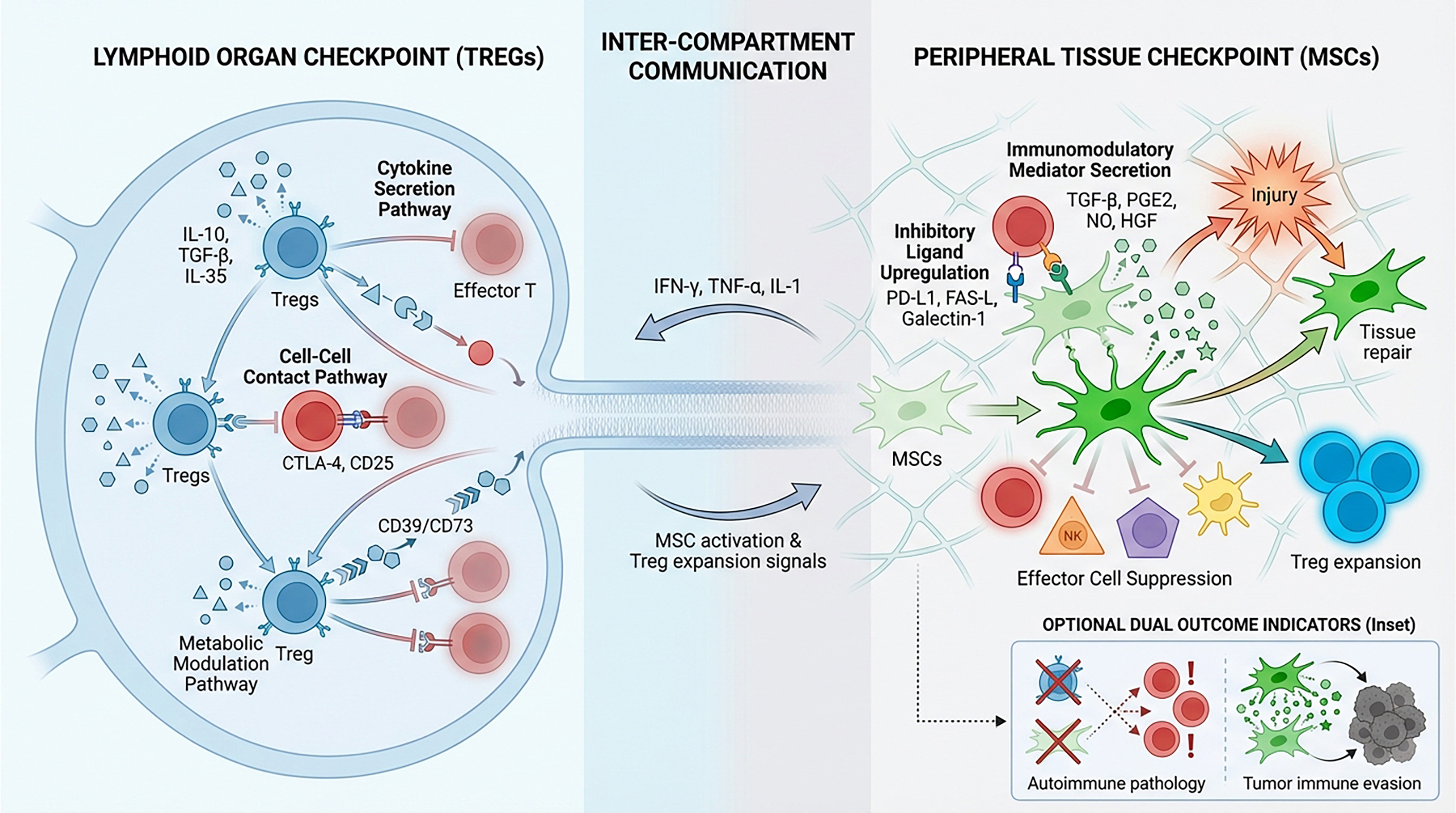

Building on these observations, I have developed a two-tier model of peripheral immune tolerance that integrates both Tregs and MSCs, with Tregs acting within the immune system as an “internal checkpoint” and tissue-resident MSCs serving as an “external checkpoint.” I argue that durable peripheral immune tolerance – particularly in the context of pathogen-induced tissue injury – can be achieved only through the combined activities of these complementary regulatory cell types.

Tregs: The peacekeepers of the immune system

A brief overview of the immune system

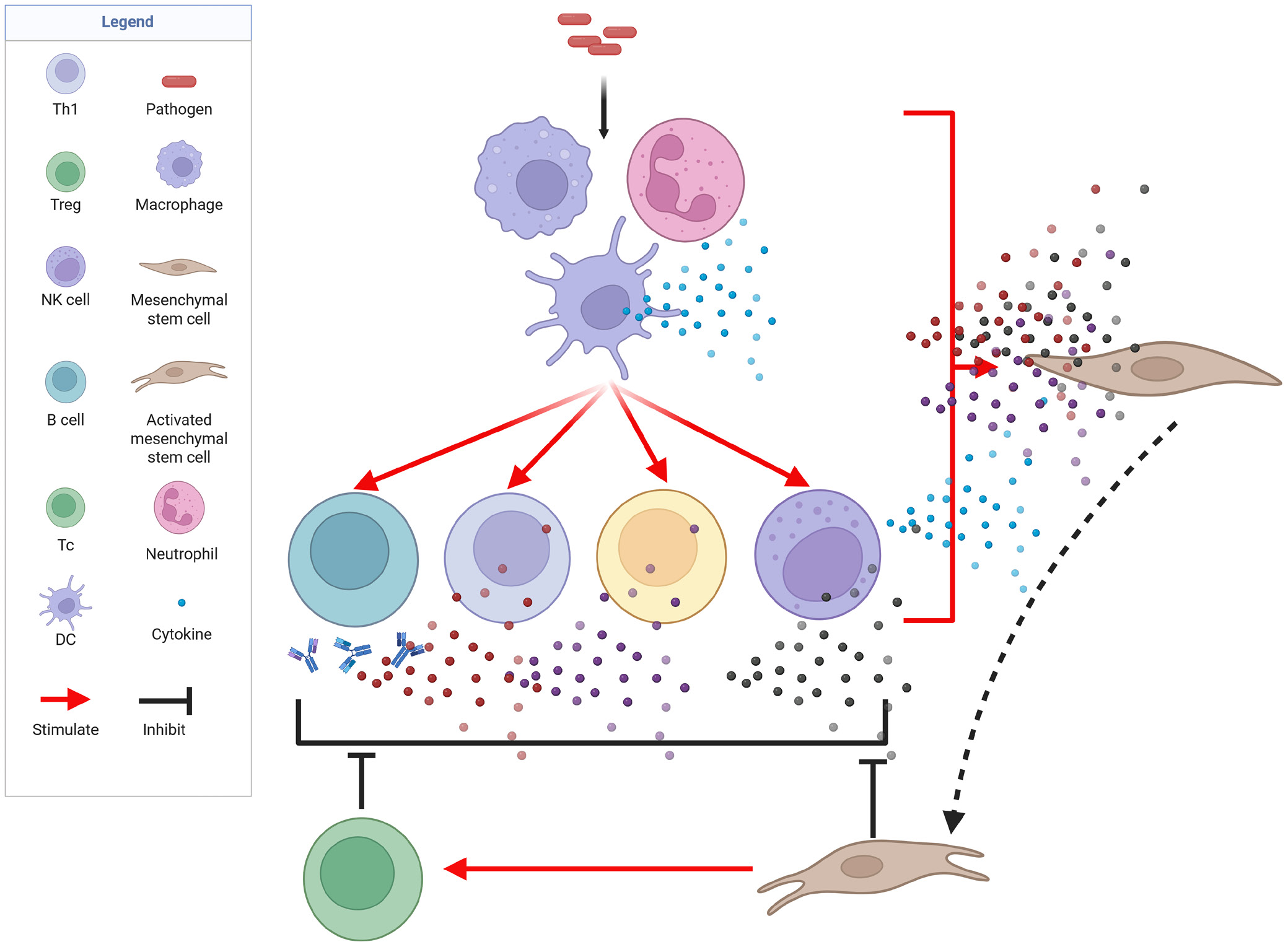

The immune system functions as a living shield that protects the host from both exogenous pathogens and aberrant endogenous cells. It is composed of highly specialized cellular subsets that together form a multilayered defense mechanism. The first barrier consists of innate effector cells – macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and natural killer (NK) cells – that are capable of immediately eliminating exogenous threats.12, 13 Concomitantly, localized inflammation is initiated, facilitating leukocyte recruitment and the containment and destruction of the pathogen. The complement system, which enhances phagocytosis and helps regulate inflammation, is also an integral component of the innate immune response. Pathogens that evade the first line of defense are targeted by the antigen-specific (adaptive) immune response. Although slower to develop than innate immunity, the adaptive response is both potent and exquisitely targeted and confers long-term immunological memory. Two principal types of lymphocytes mediate adaptive immunity: B cells and T cells. B cells are activated by professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as DCs and macrophages. Once activated, B cells secrete large quantities of antibodies that neutralize pathogens and opsonize them for phagocytosis. Some activated B cells differentiate into long-lived memory B cells, which enable more rapid responses upon re-exposure to the same antigen.12 T cells are also activated by APCs. CD4+ T helper (Th) cells orchestrate the adaptive immune response, whereas CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) directly lyse infected or transformed cells. Memory T cells are generated in parallel, ensuring a rapid response upon re-exposure to the antigen.12 Collectively, the generation of memory B and T cells enables faster and more robust protection during subsequent encounters with the same pathogen.

Regulatory control of immune activity

The immune system must be tightly regulated to prevent collateral damage to host tissues, particularly in cases of molecular mimicry (i.e., when a pathogen expresses self-like antigens). A key regulatory mechanism that limits such “friendly fire” was elucidated by Brunkow, Ramsdell, and Sakaguchi, who were awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work. They identified Tregs, a cell population that restrains autoreactive immune effector cells. This discovery helps explain why most individuals do not develop autoimmunity and how neoplastic cells can sometimes exploit immune tolerance.

Sakaguchi first postulated the existence of a suppressive T-cell subset in 1995, challenging the prevailing view that central immune tolerance in the thymus is sufficient.14, 15 In 2001, Brunkow and Ramsdell identified the genetic mutation in a mouse strain prone to fulminant autoimmunity: a loss-of-function mutation in the transcription factor FOXP3, a defect that was also found in humans.16, 17, 18 Sakaguchi subsequently demonstrated that FOXP3 is the master regulator specifying the lineage he had previously described, now formally termed regulatory T cells (Tregs).19, 20

Tregs monitor and curb aberrant immune activity through multiple non-redundant mechanisms.21, 22, 23 First, they modulate immune responses via cytokine-mediated suppression. Tregs secrete interleukin (IL)-10, which inhibits Th cells and macrophages; transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), which limits T- and B-cell proliferation and activation; and IL-35, which restrains effector T (Teff) cells. Second, Tregs suppress immune effector cells through direct cell–cell contact. Tregs express CTLA-4 and thus outcompete Teff cells for binding to APCs by engaging the costimulatory ligands CD80/CD86. They also sequester IL-2 via the high-affinity IL-2 receptor α-chain (CD25), depriving effector cells of essential growth signals. Third, in certain contexts, Tregs can directly eliminate autoreactive T cells or overactivated APCs through granzyme- and perforin-dependent cytolysis. Finally, Tregs can exert suppressive effects through metabolic modulation. The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 expressed on Tregs catalyze the conversion of pro-inflammatory extracellular ATP into immunosuppressive adenosine, which dampens Teff cell activity by binding to adenosine receptors. Through these varied mechanisms, Tregs modulate immune responses to ensure they are potent enough to eradicate pathogens, yet sufficiently restrained to preserve host tissue integrity. Thus, Tregs act as an indispensable “brake” on immune activation.

MSCs: Internal custodians of tissue homeostasis and external mediators of immune activity

Mesenchymal stem cells or master signaling cells?

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells have long been appreciated for their capacity for self-renewal and multilineage differentiation. However, their more consequential properties may be mediated by their secretome – the rich repertoire of soluble factors and extracellular vesicles they release. Accordingly, it has recently been proposed that MSCs be renamed “master signaling cells”.24

Colony-forming, plastic-adherent stromal cells were first reported by Friedenstein et al. in the late 1950s and 1960s3; however, it was not until 1991 that Caplan isolated such cells from bone marrow and characterized them.4 Subsequently, MSC-like populations were identified in adipose tissue,6 umbilical cord blood,25 Wharton’s jelly,26 the placenta,27 dental pulp,28 the dermis,29 and even hair follicles.30 To harmonize the nomenclature, the International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy proposed 3 minimal criteria in 2006: 1) plastic adherence and fibroblast-like morphology; 2) expression of CD105, CD73, and CD90, with absence of CD14, CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR; and 3) trilineage differentiation in vitro into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes.31

Due to their favorable properties, MSCs are now used clinically across a broad range of applications. For example, off-the-shelf products such as Prochymal, Ryoncil, and Temcell HS are used to treat graft-versus-host disease,32, 33, 34 whereas Cartistem35 and StemOne36 are utilized to treat osteoarthritic degeneration. The development of MSC-based therapies has ushered in a new era of regenerative medicine.

Intriguingly, the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs appears to depend less on their stemness (i.e., their capacity to directly replace lost cells) than on their potent secretome-mediated anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory functions. This realization has prompted a terminological shift from referring to these cells as mesenchymal stem/stromal cells to referring to them as medicinal signaling cells. In a previously published article, this concept was further developed, and the term “master signaling cells” was proposed as a more accurate description of MSCs, given their role as ubiquitous tissue sentinels that orchestrate signaling networks to preserve organismal equilibrium.24

The immunomodulatory activity of MSCs

With regard to the anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects of MSCs, they have been shown to promote immune tolerance.32, 33, 34, 35, 36 Accordingly, MSCs functionally parallel Tregs by helping to maintain local immune quiescence.

When exposed to a pro-inflammatory milieu rich in interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and IL-1, MSCs become activated and upregulate inhibitory ligands, such as programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), Fas ligand (FasL), galectin-1, CD73, and human leukocyte antigen G (HLA-G).37, 38, 39 Concurrently, MSCs secrete a spectrum of soluble mediators, including indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, prostaglandin E2, nitric oxide, TGF-β, and hepatocyte growth factor.39, 40 Through these factors, as well as direct cell–cell contact, MSCs suppress pro-inflammatory effector cells (i.e., Teff cells, NK cells, B cells, and DCs) while promoting the expansion of Tregs.10, 41, 42 The net result is an anti-inflammatory, tolerogenic microenvironment that promotes tissue repair and minimizes immune-mediated collateral damage.

Discussion

Given that both Tregs and MSCs play vital roles in maintaining immune homeostasis, I propose a two-tier model of peripheral immune tolerance that incorporates these internal and external checkpoints acting sequentially (Figure 1). First, Tregs in secondary lymphoid organs curb the activity of adaptive immune effector cells. Then, once activated immune cells reach the site of infection or inflammation, resident or infiltrating MSCs are stimulated to locally dampen their effector functions.

This model helps explain the encouraging clinical outcomes observed with MSC infusion in several autoimmune settings.43, 44, 45, 46, 47 However, a potential downside of MSC infusion is that the resulting broad immunosuppression may create a favorable environment for malignant cells, shielding them from CTL surveillance. The model also implies that autoimmune pathology may arise when both checkpoints are concurrently compromised.

The ubiquity of MSCs across virtually all organs likely reflects the critical importance of the tissue-level safeguard provided by these cells. Even in organs in which MSCs have not been conclusively identified, it is plausible that cells of analogous ontogeny persist in a dormant state or have differentiated into tissue-adapted subsets. Under homeostatic conditions, MSCs remain quiescent and help maintain local tissue equilibrium. When injury occurs, pro-inflammatory cytokines released by infiltrating immune cells activate MSCs, inducing a potent anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory phenotype. Thus, MSCs provide a secondary defense mechanism within tissues. In contrast to Tregs, which primarily function to suppress inflammation, MSCs are multifunctional: they simultaneously temper immune activity and orchestrate tissue repair through a repertoire of paracrine and direct cell–cell mechanisms. Therefore, we propose that MSCs be regarded as a specialized, tissue-resident extension of the immune system – a gatekeeper population that shields host tissues from collateral damage inflicted by excessive immune activation.

Conclusions

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for the identification of Tregs, which play a critical role in peripheral immune tolerance. Mesenchymal stem cells also make substantial contributions to this process, serving as an external checkpoint in peripheral tissues. Thus, to more accurately describe the mechanisms underlying peripheral immune tolerance, I propose a two-tier model in which Tregs restrain immune responses at their source, whereas MSCs serve as tissue-resident gatekeepers that swiftly extinguish excessive inflammation and generate a pro-regenerative microenvironment. Concurrent failure of these complementary elements may drive autoimmune pathology, whereas excessive immunosuppression may allow tumors to evade immune surveillance. The central role of MSCs in peripheral immune tolerance reinforces the earlier suggestion that they be renamed “master signaling cells”. In addition, the potent immunomodulatory capacity of MSCs and their ability to promote tissue repair render MSC-based interventions promising strategies for treating autoimmune diseases and tissue injury. In conclusion, my model acknowledges the roles of Tregs and MSCs in peripheral immune tolerance and highlights their contributions to ensuring that the immune system is powerful enough to eradicate pathogens, yet sufficiently restrained to safeguard the host.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.