Abstract

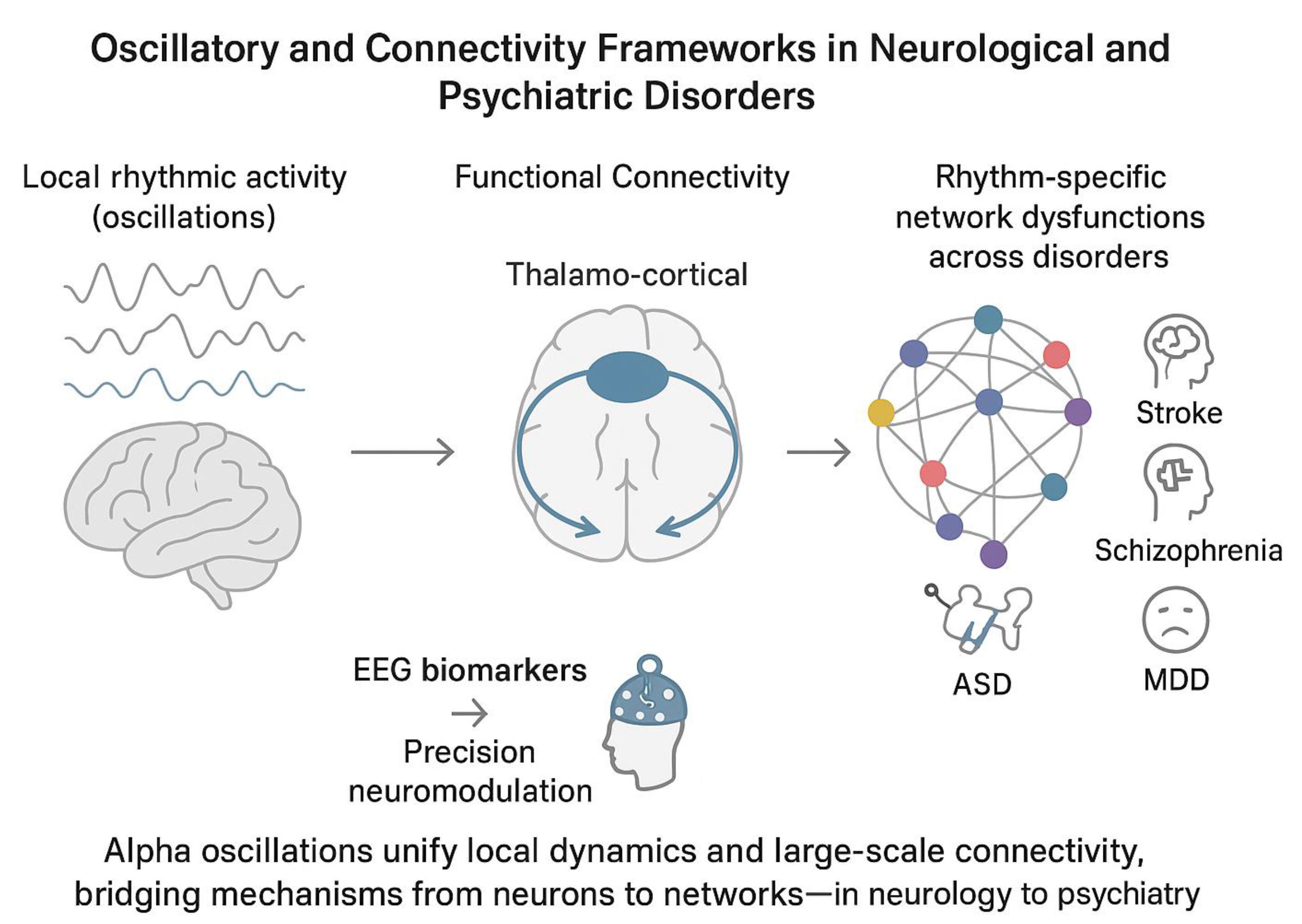

Electroencephalography has advanced from spectral analyses to integrate functional-connectivity and oscillatory metrics, offering mechanistic insights into network dysfunction across neurological and psychiatric disorders. Methodological advances, such as source reconstruction and brain modelling, enhance spatial precision and mitigate volume conduction. Empirical studies show that oscillatory brain activity and functional connectivity serve human cognition and their disruptions underlie symptoms in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders. The study of the relation between brain oscillations and connectivity is pivotal for the advances in cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Crucially, integrating these biomarkers into machine-learning frameworks and closed-loop neuromodulation holds promise for personalized diagnostics and interventions.

Key words: neuropsychiatric disorders, electroencephalography, brain connectivity, brain oscillations, clinical neuroscience

Introduction

Electroencephalography (EEG) remains an irreplaceable neuroscientific technique for probing the temporal dynamics of neural activity, combining high temporal resolution with noninvasive, cost-effective implementation at the bedside.1, 2, 3 Over the past 2 decades, EEG has evolved from simple spectral analyses to sophisticated functional connectivity metrics that capture interdependencies among cortical regions in both sensor and source spaces.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 These advances have enabled the detection of subtle network dysfunctions that correlate with clinical phenotypes in neurological and psychiatric disorders, including emerging evidence for rhythm-specific network aberrations.4, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 These approaches have promoted new insights into the neurophysiological substrates of cognition and the pathophysiology of psychiatric and neurological disorders, yet they also introduce methodological complexities that must be carefully managed.24, 25, 26, 27 In this editorial, we aim to synthesize the converging evidence on the link between brain oscillatory activity and connectivity into a focused perspective to explore pathophysiology in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

A primary challenge in EEG-based connectivity analysis arises from volume conduction and low spatial resolution at the scalp level: Signals recorded at nearby electrodes may reflect the same underlying neural source, inflating estimates of connectivity if uncorrected.9, 10, 28, 29, 30 Source-reconstruction techniques (inverse solutions) can mitigate this issue by estimating activity within cortical nodes, but they demand accurate head models to solve the inverse problem reliably,8, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 and recent reviews further underscore their broad antidepressant potential.36, 37 Consequently, the quality of the forward model and the choice of regularization parameters critically influence the accuracy of source-level connectivity estimates. Researchers must balance sensor-level convenience against the spatial precision afforded by source analyses, selecting methods that align with their hypotheses and experimental constraints. Standardized reporting of montage density, head model parameters and preprocessing pipelines is vital for reproducibility and cross-study comparisons.

Bridging connectivity and oscillatory frameworks

From a computational point of view, functional connectivity metrics and oscillatory dynamics are 2 sides of the same coin: While connectivity indices quantify the coordination between regions, oscillatory measures reflect the underlying rhythmic modes that facilitate or obstruct such coordination.38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Phase-based, amplitude-based and information-theoretic metrics each interrogate these interactions from complementary angles: 1) Phase-lag index (PLI) and its variants assess the consistency of phase differences between signals, isolating genuine interregional coupling by minimizing zero-lag artifacts10, 31; 2) Coherence metrics capture co-modulation of band-limited activities, reflecting how oscillatory fluctuations co-occur across the cortex40, 44, 45; 3) Mutual information (MI) and related entropy-based measures provide a nonlinear gauge of shared signal content, potentially revealing higher-order dependencies that linear metrics miss.46, 47 Finally, by integrating these classes of metrics, researchers can form a unified picture in which oscillations at distinct frequencies (e.g., alpha, theta) serve as communication channels whose efficacy is quantified by connectivity indices. This perspective allows for the computational integration between local oscillations and distributed functional connectivity, identifying oscillatory-specific brain functional networks. In neuroscience, the concept of metastability has been proposed as a signature that balance between these local and distributed activities in the brain. Specifically, metastability captures the brain’s ability to balance functional segregation (specialized processing in localized regions) and integration (coordinated activity across distributed networks).40, 48, 49 Metastable dynamics are thought to underpin key cognitive functions such as attention, working memory and consciousness by allowing the brain to flexibly reconfigure its network topology in response to internal and external demands.50 Theoretical models often describe metastability using nonlinear dynamical systems and coupled oscillatory activities across brain areas, demonstrating how functional integration requires segregated brain areas to influence each other in a way that facilitates integration and serve cognition and behavior.51, 52, 53 Empirical evidence from electrophysiological (EEG/MEG) studies has shown that metastable patterns characterize both resting-state and task-related brain activity,54 with alterations observed in neuropsychiatric disorders.55, 56, 57

Oscillations and connectivity: from neurology to psychiatry

Empirically, EEG-derived connectivity measures have elucidated network alterations across a spectrum of clinical conditions, revealing both shared and disorder-specific patterns for several health conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases.58 In patients with the acute phase of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, a shift in spectral power characterized by reduced activity in higher frequency bands (alpha/mu: 8–13 Hz and beta: 14–30 Hz) alongside increased power in lower frequencies (delta: 1–3 Hz and theta: 4–7 Hz) has consistently been associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes.13, 19, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 In parallel, evidence suggests that stronger connectivity within the fronto-parietal motor network during the early post-stroke period correlates with more favorable motor recovery trajectories.19, 60 Conversely, increases in connectivity occurring at later stages have been linked to less optimal functional outcomes.18, 19, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72

In disorders of consciousness (DoC), patients with unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (UWS) or minimally conscious state (MCS) show reductions in functional connectivity and oscillatory brain dynamics within large-scale default mode and frontoparietal networks correlating with clinical severity and outcomes.2, 17, 20, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83 Mutual information and coherence metrics recorded in the acute post-injury phase can predict functional outcomes with up to ~83% accuracy, highlighting their prognostic utility.2, 17, 20 Furthermore, combining multimodal connectivity metrics with complexity measures (e.g., permutation entropy) and local oscillatory activity can enhance predictive models,84, 85, 86, 87 reflecting the link between recovery trajectories and complex neural dynamics.

In patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (SSD), alpha-band synchrony deficits in SSD manifest as both reduced posterior alpha power and weakened fronto-parietal connectivity, correlating with positive symptom severity and cognitive disorganization.22, 88, 89 These aberrations align with a failure of pulsed inhibition mechanisms, leading to excessive cortical noise and impaired signal-to-noise gating.90, 91, 92, 93, 94 Similarly, beta and gamma band connectivity alterations have been linked to negative symptoms and working-memory deficits, suggesting frequency-specific network dysfunction.95, 96, 97 Integrative models propose that alterations in local processing and large-scale coordination underlie both perceptual distortions and executive dysfunction in SSD.96

In individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), EEG studies have reported long-range underconnectivity in the alpha and beta frequency bands, accompanied by local hyperconnectivity, often manifesting as elevated short-range coherence, particularly in occipital, temporal and parietal regions.98, 99, 100 Abnormal connectivity patterns, including alpha and theta coherence over frontal areas, have been implicated in atypical social perception and sensory integration.98, 101, 102, 103 Within the framework of predictive coding, these aberrant patterns are thought to reflect a deficiency in top-down predictive signaling and an overrepresentation of bottom-up error signals,104 as a consequence of a core deficit in the flexibility.

In patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), EEG recordings typically show reduced posterior alpha power desynchronization and abnormal alpha and beta-based functional connectivity during sustained attention and cognitive tasks.105, 106, 107, 108, 109 These alterations co-occur with weakened fronto-parietal connectivity, suggesting a functional breakdown in large-scale attentional and executive function networks.110, 111 Combined interventions using behavioral training and alpha-frequency transcranial alternating current stimulation (alpha-tACS) have shown preliminary success in enhancing oscillatory activity and improving executive function and attention performance.112, 113, 114, 115

In major depressive disorder (MDD), elevated frontal alpha power, particularly in the left hemisphere, and a right-to-left alpha asymmetry are frequently reported EEG features (i.e., frontal alpha asymmetry, FAA), suggesting altered interhemispheric connectivity within the prefrontal cortex.108, 109 Although limited diagnostic value of FAA in MDD,116, 117, 118 neuromodulation approaches targeting FAA have shown promising results in reducing depressive symptoms, especially those linked to motivational deficits.119, 120

Taken together, this evidence supports and demonstrates the utility of EEG-derived connectivity and spectral metrics as robust biomarkers across diverse neuropsychiatric conditions (Table 1). Future work should focus on longitudinal, multimodal studies to validate these biomarkers and explore their relationship in cognition and in the diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disorders.121

Alpha activity as a unifying lens

Based on empirical evidence and computations needed to calculate functional connectivity measures, it is plausible to hypothesize a relation between local oscillatory metrics and oscillatory-based functional connectivity. Alpha oscillations (8–13 Hz) may represent the unifying lens to understand this relation. Alpha oscillations are the dominant rhythm in the human EEG and modulate perception, attention and memory. Translational evidence consistently report both disrupted local alpha-band activity and connectivity across several neuropsychiatric disorders.21 For instance, in stroke and severe acquired brain injury, pronounced reductions in posterior alpha power, slowing of the individual alpha frequency (IAF) and weakened fronto-parietal connectivity correlate with attentional deficits and poor functional outcomes,2, 17, 18, 19, 20, 60 whereas in SSD, abnormal alpha-based connectivity is associated with psychotic symptoms and perceptual impairments.95, 96, 97 The most probable neural substrate underlying the cross-diagnostic link between alpha oscillations and functional connectivity measures is the thalamus-cortical circuitry.122, 123, 124 This brain network has been considered the generator of alpha oscillatory activity125, 126, 127, 128 and its dysfunctions yield disorder-specific connectivity signatures, ranging from hypoconnectivity in stroke to hyperconnectivity in ASD.18, 19, 98, 101, 102, 103 The hypothesis of the thalamus-cortical role in alpha generation forges the theoretical bridge between connectivity metrics and oscillatory measures, suggesting that optimized neuromodulation should aim to restore both rhythmic power and interregional synchrony. Clinically, integrating spectral and connectivity biomarkers into unified machine-learning frameworks can refine differential diagnosis, stratify patients for targeted interventions and monitor treatment response.129, 130 Establishing normative databases and open, multicenter repositories with standardized pipelines will be critical for validating hypothesis testing and improving treatment efficacy. Moreover, advances in real-time EEG processing and closed-loop neuromodulation can leverage these biomarkers for personalized treatments, such as alpha-modulation adapted to individual IAF.

Future directions

To enhance the translational impact of EEG connectivity and oscillatory research, future studies should pursue multimodal integration with structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as genomic and phenotypic data.131 This integrative approach will enable the identification of neurogenetic factors that modulate rhythmic connectivity, facilitating the development of targeted interventions.132, 133, 134 Longitudinal cohorts that track EEG connectivity trajectories across developmental stages and aging, alongside biomarkers of metabolites that modulate signals, will clarify how network dynamics confer vulnerability or resilience in neuropsychiatric conditions.135

Future research should prioritize integrative, mechanism-oriented approaches that leverage cross-frequency coupling (CFC), dynamic functional connectivity (dFC) and graph-theoretical metrics to resolve how multiscale oscillatory interactions map onto clinical phenotypes and treatment response. Cross-frequency coupling (particularly phase–amplitude coupling) has emerged as a reproducible index of mesoscale coordination and is differentially altered across psychiatric syndromes, suggesting both diagnostic and mechanistic utility.136 Complementing CFC, dFC methods allow the characterization of transient network states and state-switching dynamics that are obscured by static connectivity estimates; these transient states are likely to index symptom-relevant fluctuations in cognition and arousal but require harmonized analytic standards to ensure reproducibility.137 Graph-theoretical measures computed on EEG/MEG/fMRI networks can then quantify topology (e.g., hubness, modularity, efficiency) of both static and dynamic networks, providing compact biomarkers that are amenable to longitudinal tracking and to integration within predictive models.138 We therefore advocate for: 1) multimodal pipelines that combine source-resolved electrophysiology with hemodynamic imaging, 2) standardized connectivity analysis workflows (including surrogate testing and cross-validation), and 3) translational studies that link topology and cross-frequency interactions to cellular and circuit-level mechanisms and to neuromodulatory interventions. Collectively, these convergent approaches will improve mechanistic specificity and accelerate the translation of network biomarkers into personalized diagnostics and closed-loop therapeutics. In conclusion, by recognizing that oscillations and connectivity are inherently interdependent,22, 139 the field can accelerate the translation of EEG-derived metrics into precision diagnostics and personalized neuromodulation protocols.140, 141 This integrative framework not only deepens our mechanistic understanding of brain network dysfunction but also paves the way for novel therapeutic avenues that restore healthy rhythmic coordination across distributed neural circuits.142, 143

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.