Abstract

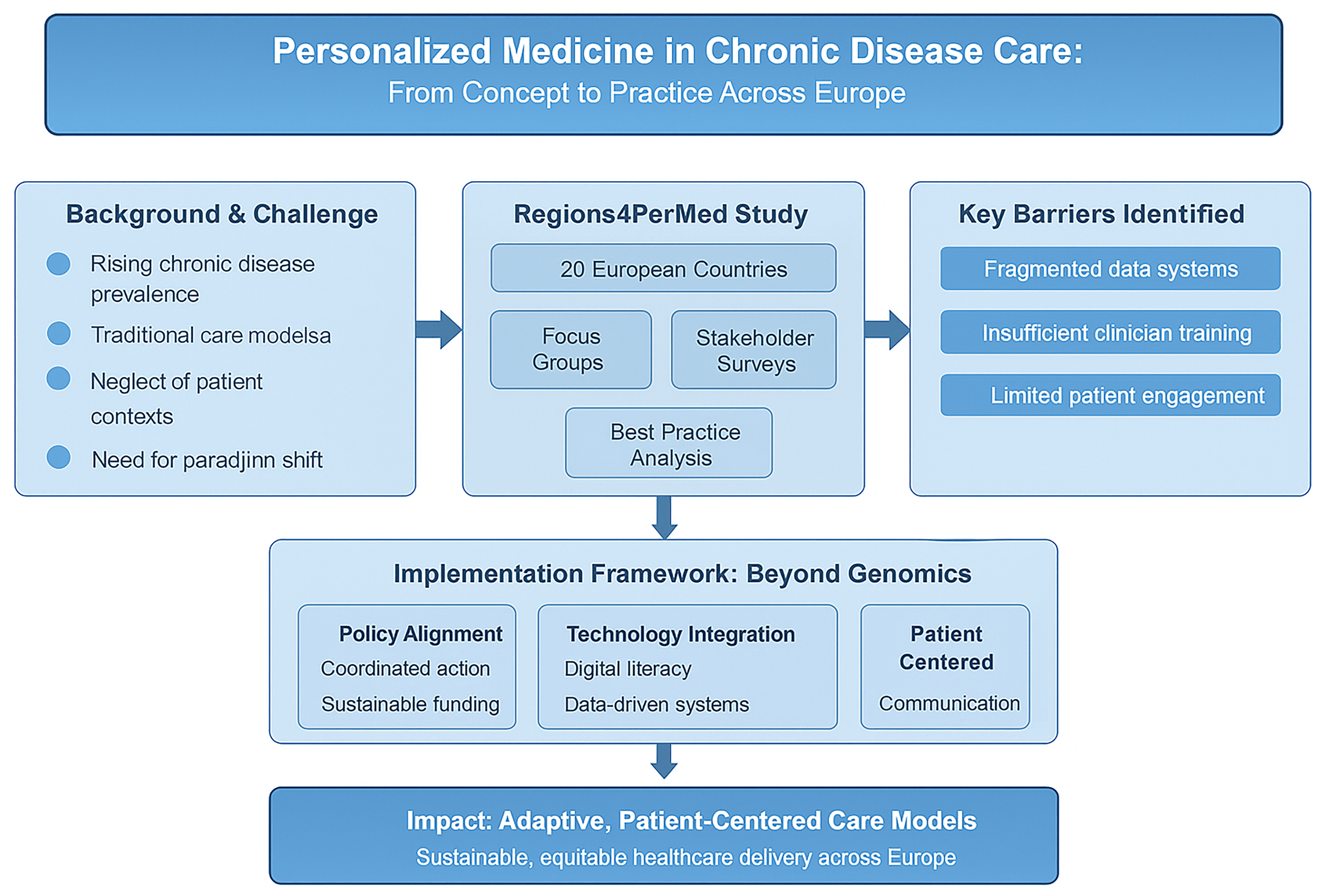

The rising prevalence of chronic diseases presents a major challenge to healthcare systems worldwide, particularly within primary care. While advances in diagnostics and therapeutics have improved disease management, traditional care models often neglect the individual contexts and lived experiences of patients. Personalized medicine (PM) offers a paradigm shift from standardized treatment approaches toward patient-specific care, integrating biological, behavioral and psychosocial dimensions to optimize outcomes. This editorial synthesizes findings from the Regions4PerMed (Horizon 2020) project, encompassing focus groups, stakeholder surveys and best practice analyses across 20 European countries. Stakeholders from government, academia, patient organizations and healthcare practice, identified key barriers to PM implementation, including fragmented data systems, insufficient clinician training and limited patient engagement. Cross-border data exchange standards, integration of real-world evidence (RWE) and sustainable funding mechanisms emerged as critical enablers of progress.

The transition from concept to practice requires aligning policy, technology and human factors. Personalized care extends beyond genomics and precision therapies to encompass communication, motivation and shared decision-making. Training healthcare professionals in holistic competencies, enhancing digital literacy and promoting trust in data-driven systems are essential for successful adoption. By reframing personalization as both a scientific and relational endeavor, PM can strengthen chronic disease care through more adaptive, patient-centered models. Coordinated action across policy, education and technology domains is vital to embed personalization into everyday clinical practice and ensure sustainable, equitable healthcare delivery across Europe.

Key words: health policy, patient-centered care, primary health care, chronic disease, personalized medicine

Introduction

The growing burden of chronic diseases poses a major challenge to healthcare systems, particularly in primary healthcare. While medical progress has improved diagnostics and treatments, care delivery often overlooks patients’ individual contexts. There is a clear shift from a “one size fits all” model toward patient-specific strategies, including targeted therapies, to achieve optimal outcomes.1, 2 Personalized medicine (PM) reflects this shift, focusing on differences between patients with the same disease and matching treatments to subgroups to improve precision and effectiveness, while also predicting individual therapy responses.

However, implementing PM faces systemic and practical barriers. Stakeholder consultations across 20 European countries highlighted the need for cross-border data exchange standards, better integration of real-world evidence (RWE) into decisions and sustainable funding. Successful implementation demands coordination between health policy, healthcare system capacity and patient organizations.3

This editorial examines the practical implications of PM, drawing on studies involving stakeholders from government, patient organizations, academia, clinical practice, and law at national and international levels. Personalized care goes beyond technology; it requires a deep understanding of the individual within the healthcare ecosystem. Key areas shaping the PM agenda include: evolving definitions, medical data systems, health policy, economic sustainability, clinical training, patient engagement, and dissemination of reliable information.

We also address barriers such as inadequate training and lack of incentives, as well as potential solutions: holistic care models, increased research investment, and development of interactive tools for self-monitoring and share decision-making. By addressing these challenges, PM can shift from concept to practice, enhancing outcomes for patients with chronic diseases.

The increasing prevalence of chronic diseases – such as cardiovascular conditions, diabetes and chronic respiratory illnesses – has become a defining feature of global health in the 21st century.4, 5 These conditions account for most morbidity, mortality and healthcare expenditures worldwide. Significant advances have been made in pharmacotherapy, diagnostics and clinical guidelines. Yet despite these developments, a critical disconnect persists between the biomedical management of chronic illness and the broader lived experience of patients.6

Personalized medicine has emerged as a promising paradigm to bridge this gap. Initially rooted in genomics and biomarker-driven treatment, the field has gradually expanded its scope to include a more comprehensive understanding of the patient. According to Epstein and Street, patient-centered communication goes beyond a clinical technique to represent a moral obligation.7 In this context, personalization must encompass not only biology, but also behavior, beliefs and biopsychosocial environments.

The findings presented in this editorial are grounded in multiple qualitative and mixed-method studies conducted within the framework of the Regions4PerMed (Horizon 2020) project. One study employed focus group methodology, bringing together stakeholders including representatives of Polish government institutions, patient advocacy organizations and financial bodies to explore barriers and facilitators to implementing PM.8 Another research phase involved a semi-structured survey of 85 respondents from 20 countries. Participants included policy officers, project managers, scientists, physicians, and legal advisors, offering diverse perspectives on PM implementation challenges and enablers at micro-, meso- and macro-regional levels. The 3rd component drew from the findings of the conference Health Technology in Connected & Integrated Care, held under the Horizon 2020 project “Interregional Coordination for a Fast and Deep Uptake of Personalized Health” (Regions4PerMed).3 The event brought together experts from academia, industry and regional and governmental health policy institutions across the EU. Best practice brochures developed within the project were also analyzed to summarize the current state of PM implementation across Europe. Analysis of European studies indicates that the implementation of eHealth and mHealth in chronic disease care requires not only technological readiness but also adaptation to patients’ skills and motivation. Barriers include low levels of digital literacy among older adults, a lack of user-friendly interfaces and fragmented legislation. Overcoming these obstacles calls for the training of healthcare professionals, the integration of data systems and the development of solutions tailored to patient needs. Consultations with stakeholders from 20 European countries revealed the necessity of developing cross-border data exchange standards, improving the integration of RWE into decision-making processes, and creating sustainable funding mechanisms. Effective implementation of PM requires coordinated action between health policy, healthcare system capacity and patient organizations. Focus group discussions emphasized that PM should balance technological advancement with socio-economic realities. Participants pointed out that international guidelines, such as those from the American Diabetes Association (ADA), already incorporate personalization by adapting treatments and prevention strategies to comorbidities, economic status and patient preferences. These complementary methods – focus groups, semi-structured surveys and analysis of best practice materials – were applied to capture both the depth and diversity of stakeholder perspectives on PM implementation across Europe.

This editorial synthesizes those findings and situates them within the broader discourse on personalized primary care. We examine how theoretical models of behavior and health regulation intersect with practical considerations in the clinical setting, and we propose directions for transforming personalization from an abstract ideal into a functional component of everyday practice.

Reframing chronic disease care: Why personalization matters

The burden of chronic diseases continues to rise globally, placing increasing demands on primary healthcare systems. While medical advancements have contributed significantly to the improved management of chronic illnesses, the human aspect of care – the unique needs, preferences and life contexts of individual patients – is too often overlooked. This disconnection between biomedical progress and holistic patient-centered care has led to growing interest in integrating PM into everyday clinical practice.

In recent years, the concept of PM has evolved beyond its molecular and genomic origins to include psychosocial, behavioral and environmental factors that shape health trajectories. Nowhere is this shift more needed than in the care of patients with chronic conditions, who often face not only the physiological burden of illness but also the psychological and social challenges of living with a long-term diagnosis. As the first and usually most continuous point of contact for these patients, the primary care setting is uniquely positioned to implement personalized care models beyond clinical protocols.

Personalization in practice: What does it mean?

Personalized care in chronic disease management should not be confused with highly technical precision medicine. While genomic data, biomarkers and advanced diagnostics have a role, personalized care at the primary care level involves recognizing the patient’s lived experience and aligning interventions with their values, beliefs and capabilities.

This means asking “What is the matter with the patient?” and “What matters to the patient?”. It means exploring motivation, readiness to change, perceived control over health, and social support systems – all of which influence behavior and outcomes. For example, systematic reviews confirm that a higher sense of coherence is positively associated with health-promoting behaviors – including physical activity and healthy eating – and negatively associated with risk behaviors.9 Moreover, population-based data analyses indicate that better subjective health perception, regardless of objective disease status, is linked to improved health behaviors such as normal weight, proper sleep and regular exercise.10 Recognizing and responding to these factors requires time, empathy, and often a rethinking of how clinical encounters are structured. Tools such as motivational interviewing, brief behavioral interventions and risk stratification models can support clinicians in integrating personalization into routine visits.11 As evidenced by findings from both the focus group discussions and stakeholder surveys, real-world examples of personalized care are already emerging across Europe. For instance, national initiatives in primary care in Poland, Germany and Italy have introduced personalized lifestyle coaching combined with remote monitoring tools for patients with diabetes and heart failure. These programs use mobile health applications and telemonitoring systems to track symptoms and treatment adherence, enabling clinicians to dynamically adjust care plans based on real-time patient feedback.3, 4, 8 However, the most critical ingredient is clinician awareness – an openness to understanding the person behind the patient.

The data dilemma: Integration, protection and validity

Effective personalized care depends on the thoughtful collection and use of patient data. However, significant obstacles remain. In our studies, stakeholders expressed concerns about data fragmentation, limited system interoperability and a lack of standardization. The ethical dimension is equally important – particularly about data security, privacy and the potential misuse of health information.12

Participants also noted that personalized therapies offer great promise but often apply to narrowly defined patient populations, making it difficult to generate robust, generalizable evidence. Cross-border collaboration and harmonization of legal frameworks were seen as essential steps to enable data-driven personalization that is safe, trustworthy and beneficial for patients across diverse healthcare systems.13

Recent studies also highlight how artificial intelligence (AI)-driven predictive models can enhance data interpretation and support early intervention in chronic disease management, further strengthening the potential of personalized care pathways.14, 15

Systems in transition: Policy, regulation and the role of evidence

The successful implementation of PM depends heavily on coherent health policies and political will.16 Our findings, based on qualitative focus group discussions and cross-national survey data collected from policymakers and healthcare stakeholders in 20 European countries, revealed that the regulatory landscape across Europe remains fragmented, characterized by lengthy legislative cycles and inconsistent funding structures. These factors delay the translation of innovative practices into routine care.

A recurring recommendation from our respondents was the need to scale up the dissemination of RWE and best practices. This would demonstrate the value of personalized care and support advocacy efforts aimed at integrating personalization into national health strategies. Structural reforms – such as the appointment of case managers or patient navigators – were also cited as promising enablers of change.

Financing the future: Economic models for personalized medicine

The economic sustainability of PM is a central concern. On the one hand, PM offers the potential for long-term cost savings by avoiding ineffective treatments and reducing hospitalizations. Conversely, the high costs of specific targeted therapies – especially for small patient subgroups – pose challenges to reimbursement and equity.17

Stakeholders emphasized the importance of rigorous cost-effectiveness analysis and flexible funding models. Public payers and insurers should be equipped to evaluate the value of innovation in terms of clinical efficacy and through the lens of quality of life and long-term outcomes. Furthermore, respondents emphasized that successful pilot programs must be adequately supported beyond their initial funding cycles to ensure a sustainable impact.

The practitioner’s role: From specialist knowledge to holistic competence

A transformative approach to clinician education is essential for realizing personalized care. Many medical professionals are still trained primarily in disease-specific silos, with limited exposure to behavioral science, patient communication and interprofessional collaboration. This makes it difficult to engage patients as active participants in their care.

Our findings suggest that medical training should emphasize holistic competencies –including empathy, active listening and cultural sensitivity – as foundational skills for all healthcare professionals. Personalized medicine is not just a clinical model, but a relational one, requiring a mindset shift as much as a skillset expansion.18

Empowered patients: Engagement, education and digital trust

Personalization also requires a new kind of patient who is informed, engaged and confident in navigating digital health tools. Respondents highlighted the need to strengthen digital literacy, ensure transparency in data use, and involve patients in the design of tools and services.19 Findings from qualitative and quantitative studies also pointed to the growing role of distance monitoring in chronic disease management. Participants noted that digital tools, such as mobile health apps and wearable sensors, can enhance patient engagement by providing continuous feedback and enabling more responsive, personalized interventions.3, 4, 8

Patients should also be educated about the potential benefits of data sharing,20 as public support for the implementation of personalized medicine policies (PMPs) in routine care is crucial – not only due to the high financial costs involved but also because of the potential diversion of resources from other healthcare services.21

When patients are empowered with information and feel their voices are heard, they are more likely to adhere to treatment, participate in self-care and experience greater satisfaction. Building trust in the digital ecosystem – through robust data protection, clear communication and co-creation strategies – is integral to the personalization agenda.

Spreading the word: Why dissemination is not optional

A frequently overlooked component of PM implementation is the dissemination of knowledge. Our research indicates that public awareness of personalized care remains limited, particularly outside academic and specialist settings. Strategic communication – via traditional media, digital platforms and community engagement – is essential to foster acceptance and demand.22

Stakeholders stressed the importance of sharing success stories and scientific findings with the broader public, including patients and caregivers. Widening access to understandable, evidence-based information is key to building a supportive environment for personalized innovation.

Conclusions

As the epidemiological landscape shifts toward the predominance of chronic diseases, the importance of personalized care in primary care settings becomes increasingly evident. Our findings, together with those of others, point toward a future in which medical practice is scientifically informed, emotionally intelligent, socially conscious, and behaviorally adaptive.

Personalized care is not a luxury reserved for cutting-edge institutions – it is a necessity that can and should be embedded into everyday practice. The first step toward that future is to recognize the diversity of patients – not only in their diagnoses, but also in their experiences, values and capacities. The second is to build systems and develop skills that translate this recognition into practice.

Moreover, findings from qualitative studies and patient narratives highlight the necessity of integrating emotional, cognitive and relational dimensions into care planning – especially in the context of increasingly complex needs among individuals with chronic conditions.23, 24 Addressing these needs requires empathy and communication, as well as digital technologies that enable real-time health monitoring, information exchange and shared decision-making.3

Strategies grounded in a holistic, biopsychosocial approach – supported by technological solutions and embedded within secure and regulation-compliant (e.g., General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)) information systems – have the potential to significantly improve treatment adherence, satisfaction with care and health outcomes.8

If we are to improve outcomes for people living with chronic illness, we must begin not just with protocols, but with people. In the European context, where healthcare systems and policies remain diverse yet increasingly interconnected, these insights highlight the shared need for harmonized, patient-centered strategies in chronic disease management.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.