Abstract

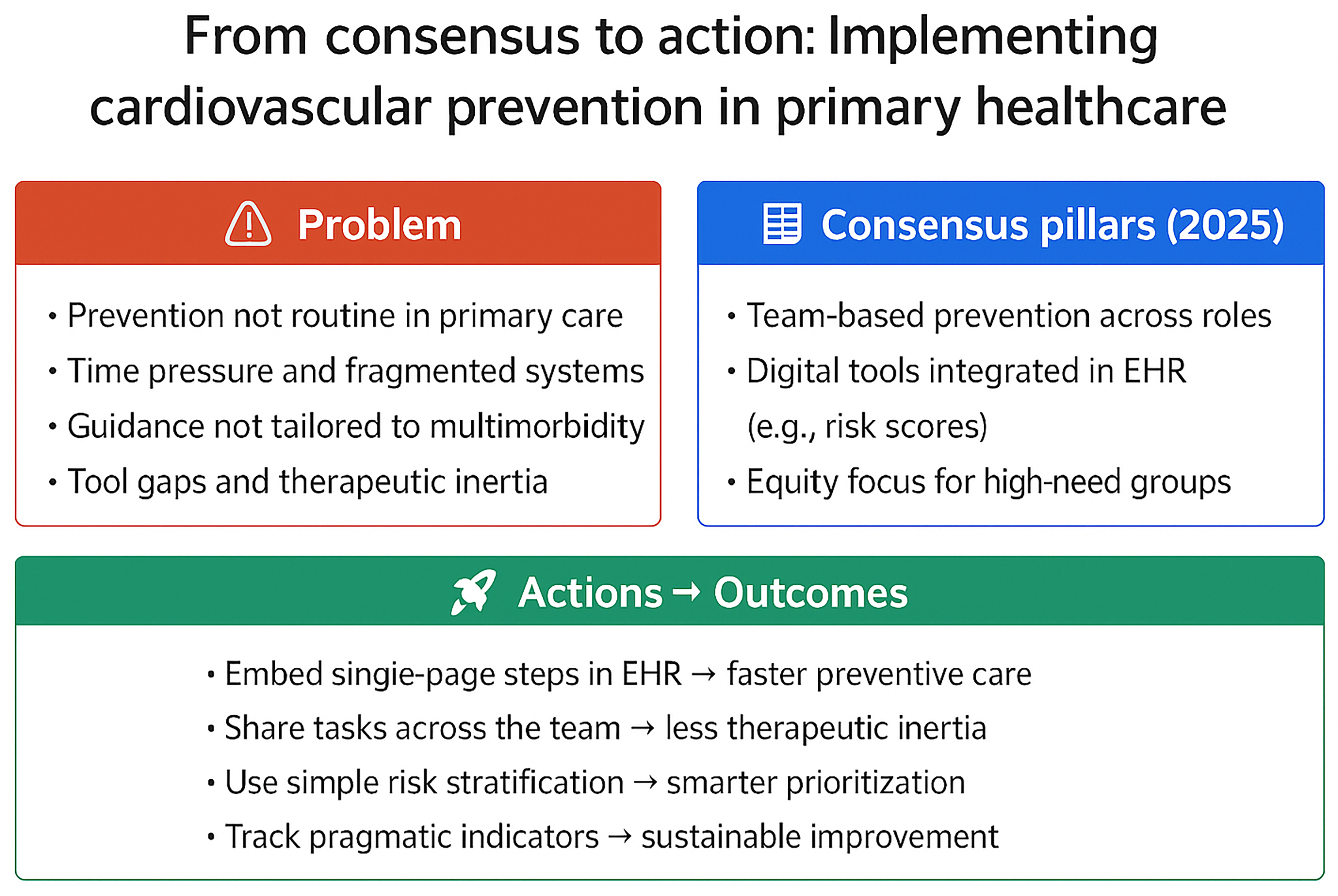

Cardiovascular prevention guidelines are based on robust evidence, yet their implementation in primary healthcare remains inconsistent due to systemic barriers, workload pressures and insufficiently adapted tools. The 2025 European consensus emphasizes the need for multidisciplinary teamwork, digital innovation and equity-focused strategies to strengthen prevention across diverse healthcare systems. Translating these recommendations into actionable, context-specific approaches is essential to close the evidence-practice gap and improve population cardiovascular outcomes.

Key words: primary healthcare, cardiovascular diseases, implementation science, preventive health services, guideline adherence

Introduction: From guidelines to everyday practice

The past 2 decades have witnessed a proliferation of cardiovascular prevention guidelines produced by national, European and global professional societies. Their scientific quality is rarely questioned; most are grounded in robust evidence and formulated through rigorous consensus processes. Yet, many of these recommendations cannot be implemented equitably at scale in real-world practice. As the frontline of prevention and long-term management of cardiovascular disease (CVD), primary healthcare has a pivotal role, but systemic and structural barriers frequently constrain implementation efforts. The paradox is striking. Even though we now possess unprecedented knowledge about reducing cardiovascular risk, incorporating this evidence into routine clinical care continues to pose a significant challenge. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the fragility of preventive services and amplified existing inequities.1 Although the acute disruptions have eased, persistent health inequalities – driven by structural determinants – remain a key obstacle to improving cardiovascular outcomes.

Several factors underpin this gap. Primary care clinicians face heavy caseloads, limited consultation times and competing priorities. Guidelines, frequently designed with hospital-based populations in mind and without adequate consultation with primary care providers, may not fully account for the complexity of multimorbidity or the social determinants of health that shape outcomes in the community.2 Moreover, the lack of standardized tools for continuous professional feedback and quality improvement limits effective implementation.3 The consequence is a pattern of underdiagnosis, therapeutic inertia and wide disparities in preventive care across Europe.

Against this backdrop, the 2025 scientific statement jointly issued by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Council for Cardiology Practice, the Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions, WONCA (World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians) Europe, and European Rural and Isolated Practitioners Association (EURIPA) represents a critical step forward.2 By explicitly addressing the realities of primary care, it seeks to harmonize recommendations, highlight implementation gaps and promote system-level engagement. Its central message is clear: Cardiovascular prevention cannot succeed without stronger integration of guidelines into the daily practice of general practitioners, nurses and allied professionals.

Why is implementation so difficult?

Despite decades of progress in cardiovascular medicine, translating preventive recommendations into primary care remains fraught with obstacles. One of the most persistent is the structural fragmentation of healthcare systems across Europe. Such gaps are difficult to overcome, since they reflect structural differences in how health systems are organized. While complete harmonization across countries is unlikely, progress may come from shared principles and adaptable coordination models.

At the same time, primary care professionals carry a workload that continues to expand in volume and complexity. Rising numbers of older patients with multimorbidity, coupled with limited workforce growth, leave general practitioners and nurses with little time to address prevention systematically. Large multicountry programs consistently document these shortfalls, including suboptimal risk factor control and persistent care gaps in patients with multimorbidity.4, 5

Another major challenge lies in the limited availability of locally adapted tools that fit into the daily routines of family practice. Risk calculators, decision support systems and patient education resources often remain inaccessible, overly complex or poorly integrated into electronic health records. This limits their use during short consultations and reduces their relevance in resource-constrained environments.

Finally, clinicians face a paradox of abundance. The sheer volume of guidelines produced by multiple professional bodies, each with nuanced recommendations, creates confusion rather than clarity.6 Without concise, operational guidance adapted to primary care realities, preventive cardiology risks remaining aspirational rather than actionable,7 a conclusion echoed by EUROASPIRE V/VI4 and AFFIRMO,5 which highlight the gap between recommendations and everyday delivery of care.

Key messages of the consensus

The 2025 consensus highlights that prevention cannot be delivered by physicians alone. Multidisciplinary and team-based models are the foundation of effective cardiovascular risk management. General practitioners, nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, psychologists, and community health workers each bring complementary expertise that can improve adherence and continuity of care. The most tangible pathway to scaling prevention across European health systems is shifting from a physician-centered to a team-centered approach. Digital innovation is another defining feature of the statement. Integrating telemedicine and decision support into everyday workflows offers the potential to extend the reach of primary care, particularly in underserved or remote regions. Technology should be regarded as an enabler rather than a substitute for clinical judgment. The challenge is to ensure that digital tools are interoperable, user-friendly and accessible across settings with variable resources. Ongoing training in digital literacy for healthcare staff is essential to maximize the benefits of these innovations.

The document draws special attention to vulnerable populations. People with multimorbidity, migrants and residents of rural or deprived communities often experience systematic disadvantages in access to timely prevention.8 The consensus sets a benchmark for more inclusive cardiovascular health strategies by explicitly acknowledging these groups. It frames prevention as a biomedical issue and a matter of equity and social responsibility. Including clinical illustrations such as chronic venous disease, elevated lipoprotein(a) and inflammatory rheumatic disorders exemplifies the need for broader thinking in primary care. These examples highlight conditions that cut across specialties, often overlooked in standard prevention frameworks, yet highly relevant to everyday practice.9 Their selection signals a call to widen the lens of cardiovascular prevention and adapt strategies to the complex realities of patients in primary care.2 The consensus also emphasizes the importance of ongoing professional development to keep abreast of new scientific evidence and improve communication skills, cultural competence and motivational interviewing – core elements of effective preventive counseling across diverse populations.

Implications for general practitioners

For general practitioners, the challenge is translating recommendations into the constraints of a brief consultation and keeping pace with the increasing complexity of evolving guidance, which reinforces the need for continuous professional development. With only 10–15 min available, including the time required to review prior history and document decisions, preventive cardiology must often be reduced to its most pragmatic elements. While longer consultations would be preferable, realistic prioritization and alignment with patient expectations remain essential. This requires focusing on tools and approaches that can be used efficiently, without adding excessive burden to already crowded agendas.

Risk assessment remains the cornerstone of prevention. Instruments such as SCORE2 or mobile-based calculators allow rapid cardiovascular risk estimation and seamlessly integrate into electronic health records. Their most significant value lies in enabling clinicians to stratify patients quickly, identify those requiring intensified intervention and open conversations about behavior change. To be effective, these tools must be simple, reliable and embedded into clinical routines rather than existing as standalone resources.10

Equally important is the emphasis on shared decision-making and personalization of therapy, yet these processes are time-intensive and difficult to achieve fully within the constraints of short consultations. Preventive care gains credibility and durability when it reflects patient values and priorities. General practitioners who engage patients in goal setting, acknowledge barriers and tailor interventions are more likely to achieve sustainable behavior changes and treatment adherence.

The role of the general practitioner must also be understood within a broader team context. Nurses, pharmacists and link workers can take responsibility for education, follow-up and care coordination. By redistributing tasks across a multidisciplinary team, preventive strategies become more feasible and less dependent on the physician alone.11 This team-based approach is essential to bring guidelines to life in the day-to-day practice of primary care.12 It is important to note that digital literacy and adequate training in decision support tools are prerequisites for successful implementation, ensuring that technologies reduce, rather than increase, the workload of physicians.

The evidence-practice gap

The promise of cardiovascular prevention remains only partially realized, with wide gaps between evidence and routine practice. Persistent regional inequalities across Europe illustrate the challenge. In some countries, structured prevention programs and strong primary care systems have delivered measurable progress, while in others, resource limitations and fragmented services have left high-risk populations without consistent support. Such variation reflects not only differences in funding but also disparities in health literacy, workforce capacity and political commitment to prevention.

Even where guidelines are well disseminated, clinical targets remain poorly achieved. Rates of optimal control for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure and glycemia are consistently inadequate. This failure is not simply the result of patient non-adherence but also of therapeutic inertia, insufficient follow-up and the absence of systematic monitoring within primary care.13 The consequence is that millions of Europeans live with preventable cardiovascular risk that remains unaddressed despite clear evidence on how to reduce it.

Compounding the problem is the lack of reliable indicators to assess implementation in real-world practice. Most health systems can report prescription volumes or hospital outcomes, yet very few collect data on whether preventive strategies are delivered during primary care consultations. Without suitable ways to assess implementation, quality improvement efforts risk lacking direction and accountability. However, indicators alone are unlikely to provide the solution unless co-designed with practitioners and embedded in supportive systems. The development and integration of standardized processes and outcome measures within electronic health systems are urgently needed to close this gap.14

Closing the evidence–practice gap requires a stronger focus on real-world evidence and practice-based research. Embedding pragmatic trials and observational studies in everyday primary care would provide the insights needed to adapt guidelines, overcome barriers and deliver prevention that is both evidence-based and feasible in daily clinical work.15 Equally important is patient participation in the co-design of prevention strategies, where patients act not simply as recipients of care but also as partners in developing, testing and refining interventions that fit their life realities.16

The rural primary care setting

The specificity of the rural primary care setting deserves a more profound analysis. Rural primary care teams face persistent barriers to following CVD prevention guidelines, including workforce shortages, brief consultations and competing acute demands that crowd out structured prevention.2 Limited on-site diagnostics and referral bottlenecks (e.g., natriuretic peptide testing and echocardiography access) delay risk stratification and timely treatment initiation. Fragmented information flows and poor interoperability of electronic systems hinder the use of decision support, audits and shared records across dispersed services.17

Guidelines are often lengthy and hospital-centric, offering insufficiently tailored, feasible steps for multi-morbid, older patients commonly seen in rural practice. Socio-economic determinants – lower health literacy, travel costs and limited access to nutritious food – compound adherence challenges and widen prevention gaps. Time constraints and digital literacy gaps reduce uptake of risk tools (e.g., SCORE2/QRISK) and undermine shared decision-making during short visits. Telehealth and remote monitoring could mitigate distance barriers, but added data processing and workflow burden can offset benefits without resourcing. Policy-level enablers (e.g., European Health Data Space; national CVD strategies) require local funding and adaptation to become usable in small practices.

Overall, practical, concise and context-adapted guidance – embedded into interoperable IT with team-based pathways – is essential to close rural implementation gaps.16, 18 Community collaborations, such as those involving local schools, employers and municipalities, can expand prevention efforts beyond clinics and help create healthier rural environments. A short, structured self-care coaching intervention combined with assessment of caregiver contribution is beneficial in rural settings.19

A system-level perspective

Sustainable cardiovascular prevention depends not only on clinical knowledge but also on the organization of health systems. What is required are prevention models that are simple, scalable and financially sustainable.15 Strategies must focus on streamlined pathways that can be delivered consistently across diverse settings, from urban centers to rural practices with limited resources.

European and global health policies provide a framework for such efforts. The European Health Data Space promises to improve data interoperability and facilitate monitoring of preventive care. Initiatives such as the European Commission’s Healthier Together strategy and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) commitment to Universal Health Coverage underline the importance of equity in prevention. These frameworks highlight the need for patient-centered, transparent and accountable systems.

Yet, international declarations alone are insufficient. Translation into local practice requires strong national strategies, adequate funding and political will. Primary care providers must be supported by reimbursement schemes, workforce planning and digital infrastructure that make prevention practical and sustainable. Policy strategies that enable integrated healthcare and build strong multidisciplinary healthcare networks to enhance interprofessional communication and referral pathways are also crucial to implementing recommendations in primary care settings.19

Cardiovascular prevention will remain fragmented and uneven without alignment between global ambitions and national implementation.

Innovations and the future of prevention

The future of cardiovascular prevention in primary care may be shaped by innovations that extend beyond traditional models of care. Remote monitoring and telehealth are already transforming the management of chronic conditions.20 Continuous tracking of blood pressure, heart rate or rhythm through wearable devices enables earlier detection of deterioration and more timely interventions.21 Artificial intelligence applied to these data streams offers the possibility of personalized risk prediction and decision support that adapts to the complexity of multimorbidity often encountered in general practice.

At the same time, personalized medicine must move beyond genomics to encompass psychosocial and cultural determinants of health. Effective prevention depends on biological risk and behaviors shaped by family dynamics, education, employment, and community environments. Recognizing and integrating these determinants into risk assessment and management strategies can make preventive care more relevant and sustainable.22

Community resources represent another frontier for innovation. Link workers, peer support groups and culturally adapted education programs help bridge gaps between clinical advice and lived reality.23 Religiosity and spirituality, too often overlooked in biomedical discourse, may provide resilience, reduce stress and encourage adherence to healthy behaviors. Incorporating such dimensions does not replace evidence-based medicine but enriches it, anchoring prevention in the context of patients’ lives.24

Taken together, these innovations point to a future in which prevention is more technologically sophisticated and more human-centered. The challenge will be integrating digital advances with social and cultural realities, ensuring equitable access and meaningful outcomes.25

Call to action

The implementation of cardiovascular prevention in primary care represents a dual challenge that is both medical and societal. Success requires the rigorous application of evidence-based medicine combined with explicit recognition of the social, cultural and economic determinants that shape health behaviors and access to services. Without an integrated perspective, guidelines risk remaining scientifically robust but operationally ineffective, with limited impact on population-level outcomes.

Strengthening the evidence base specific to primary care is a critical priority. Recommendations relying on hospital-based studies do not adequately capture the multimorbidity, diagnostic uncertainty, and socioeconomic diversity characteristic of community populations. Pragmatic trials, practice-based research networks and real-world evidence are necessary to evaluate preventive interventions’ feasibility, effectiveness and scalability within everyday consultations. In parallel, sustained investment in education and professional development is required to equip clinicians with the competencies to deliver high-quality prevention in settings constrained by time and resources. Guidelines must evolve toward simplicity and operational clarity, providing concise and actionable recommendations bridging the research and practice gap.

International collaboration remains central to progress. Professional societies, policymakers and patient organizations should work collectively to promote coherent standards while allowing adaptation to national and local contexts. Equity must be the guiding principle, ensuring that vulnerable populations are prioritized in implementation strategies.26

The consensus statement provides a critical platform. The next step is to translate shared aspirations into coordinated action that strengthens primary care and mitigates the global burden of CVD. A transition from aspiration to implementation requires naming specific levers that can be activated without adding complexity to already pressured primary care. At system level, embedding concise and context-adapted preventive steps into existing electronic workflows – rather than creating parallel processes – is essential to make adherence feasible during brief consultations. Implementation can further be enabled through financing schemes that allow redistribution of preventive tasks within multidisciplinary primary care teams, and through co-design of care pathways with patients and communities to ensure cultural fit, equity and uptake across heterogeneous settings.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.