Abstract

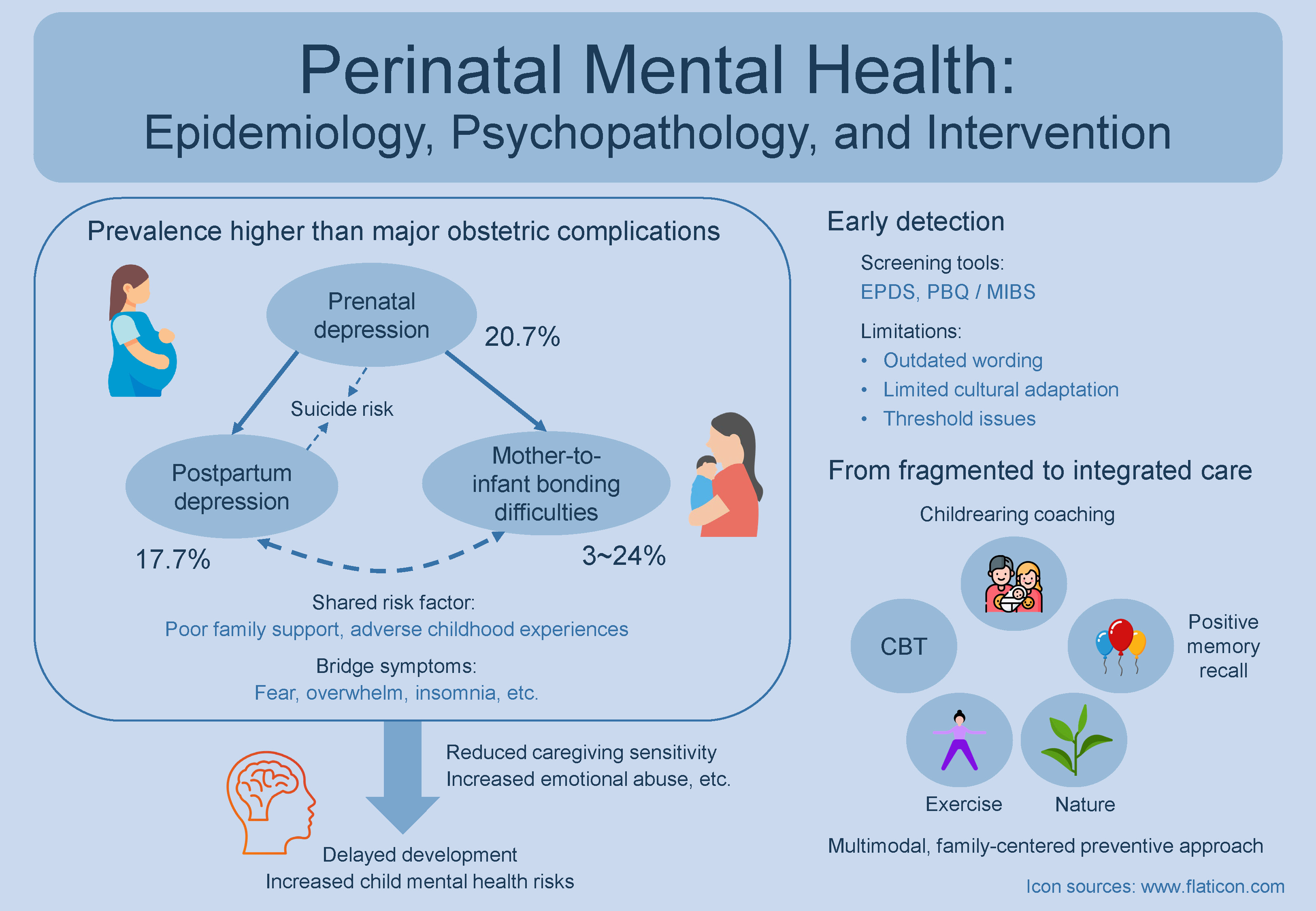

Perinatal mental health has been increasingly recognized as one of the most prevalent and consequential complications of pregnancy and childbirth. Approximately 1 in 5 women experience depression during or after pregnancy, and up to 1 in 4 encounter difficulties in establishing an emotional bond with their infants – a condition known as mother-to-infant bonding difficulties (MIBD). Pooled global estimates from meta-analyses indicate that these conditions are more prevalent than major obstetric complications such as gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. They also represent the leading cause of maternal mortality, particularly in high-income countries. For example, suicidal ideation (SI) is approx. 16 times more common among women with postpartum depression (PPD) than among those without. Moreover, SI occurring alongside PPD is often associated with prior depressive episodes and a lack of social support, whereas SI in the absence of depression tends to be linked to first-time motherhood, infection during pregnancy, or loneliness. Postpartum depression and MIBD are also closely interconnected, exhibiting a bidirectional relationship and sharing major risk factors such as prenatal depression, limited family support, and adverse childhood experiences. When left untreated, perinatal depression and MIBD can impair maternal functioning and delay infants’ emotional, cognitive and social development. Emerging integrative approaches that combine psychotherapy with bonding-focused, lifestyle and psychosocial components show promise in improving outcomes. Future research should focus on developing comprehensive, multimodal interventions that integrate psychotherapy with lifestyle and psychosocial elements within a preventive, family-centered framework, promoting sustained recovery beyond active treatment.

Key words: perinatal depression, mother-to-infant bonding, suicidal ideation, adverse childhood experiences, infant development

Introduction

Perinatal mental health refers to the psychological well-being of women during pregnancy and the 1st year after childbirth. Recognized as common and consequential for mothers, infants and families,1, 2, 3 this field has gained global attention. This overview summarizes recent advances in perinatal depression, including prenatal and postpartum, and mother-to-infant bonding difficulties (MIBD), highlighting progress in epidemiology, psychopathology and intervention.

Prevalence and epidemiological trends

Perinatal mental disorders are among the most frequent complications of pregnancy and childbirth, often surpassing major obstetric complications. Meta-analyses reported a pooled global prevalence of 20.7% (95% confidence interval (95% CI): 19.4–21.9%) for prenatal depression4 and 17.7% (95% CI: 16.6–18.8%) for postpartum depression (PPD).5 While global estimates for MIBD are unavailable, community-based surveys report prevalence rates ranging from 3%6 to 24%,7 based on cutoff scores from the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ)8 or the Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale (MIBS).9

In contrast, major obstetric complications typically occur at lower frequencies: gestational diabetes mellitus – 14.0% (95% CI: 13.97–14.04%)10; preeclampsia – 4.6% (95% CI: 2.7–8.2%)11; preterm birth – 10.6% (95% CI: 9.0–12.0%)12; and postpartum hemorrhage – 10.8% (95% CI: 9.6–12.1).13

Therefore, perinatal mental disorders represent leading morbidities during pregnancy and the postpartum period, and they are also major contributors to maternal mortality.14 In UK surveillance data, suicide was the leading direct cause of death from 6 weeks to 12 months postpartum, accounting for 39% of late maternal deaths.15 Similar findings have been reported in other high-income countries, such as the Netherlands, where suicide accounts for 28% of maternal deaths.16 This mortality pattern underscores the critical importance of assessing and managing suicidal thoughts and behaviors during the perinatal period.

Importantly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of perinatal depression and MIBD increased markedly across different populations.17, 18, 19 For example, the pooled global prevalence of prenatal depression and PPD has been estimated at 29% (95% CI: 25–33%) and 26% (95% CI: 23–30%), respectively,20 consistent with findings from another meta-analysis reporting similar estimates.21 This increase likely reflects heightened social isolation, fear of infection, and reduced access to perinatal care and support services.

Psychopathology and clinical features

Perinatal depression shares core symptoms with major depressive disorder, including low mood and anhedonia.22 The uniqueness of perinatal depression is that it manifests in the specific context of pregnancy, childbirth and childbearing, where biological influences, including genetic vulnerability and hormonal fluctuations, play a prominent role.23 Consistent with the mortality data described above, severe cases of perinatal depression may involve thoughts of suicide14, 15, 16 or harming the infant,24 which requires urgent response.

A key concern is the strong association between perinatal depression and suicidal ideation (SI),25, 26, 27 in which SI primarily occurs in women with perinatal depression, be it prenatal or postpartum. For instance, it has been estimated that SI is about 16 times more common in women with PPD.27 When SI occurs without PPD, it shows distinct predictors.27 In women with PPD, SI links to prior depressive episodes and lack of support (e.g., being single, canceled family visits). Without PPD, SI relates to first-time motherhood, infections during pregnancy, or loneliness aggravated by COVID-19. These distinctions underscore the need for context-sensitive risk assessment.

Another robust finding is that prenatal depression represents a strong predictor of PPD. A meta-analysis of 88 cohort studies found that about 37% of women with prenatal depression later developed PPD, representing a 4.6-fold higher risk compared with those without prenatal depression.28

Finally, the close interrelationship between PPD and MIBD has been increasingly documented. Cross-sectional data indicate that more than half of women with PPD experience MIBD, while up to 40% of those with MIBD also have PPD.19 The 2 conditions not only show reciprocal influences on each other,19 but also share major risk factors such as prenatal depression,28, 29 poor family support30, 31 and adverse childhood experiences.32, 33 Network analyses identify overlapping “bridge symptoms” (e.g., fear, overwhelm, insomnia) that vary across postpartum stages,19 which emphasizes the need for dynamic, stage-sensitive care. Moving forward, adopting dimensional and biologically informed analytic frameworks34, 35 may help disentangle the shared and distinct mechanisms underlying this high comorbidity, paving the way toward more personalized preventive and therapeutic interventions for mothers and infants.

Impact on mothers and infants

Untreated perinatal depression affects not only the mother but also her overall health and caregiving capacity. Women with depression often experience difficulties in daily functioning and are more likely to develop physical conditions such as hypertension.36, 37, 38 Beyond the impact on their own wellbeing, they may also struggle to respond sensitively to their infants.1, 39, 40

They may display flat or negative affect, breastfeed less frequently, adopt unsafe sleep practices, and neglect preventive healthcare measures such as vaccinations. Depressed mothers are also more likely to use harsh discipline or engage in abusive behavior.1, 39, 41, 42, 43 These challenges contribute to suboptimal caregiving environments that can hinder infant development.

Evidence consistently links maternal depression to cognitive, language, and socioemotional delays, as well as an increased risk of mental health problems in offspring.44, 45, 46 Likewise, unresolved MIBD the risk of emotional abuse and perpetuates maternal depression,19, 47 leading to disrupted infant emotional48, 49 and cognitive development.50

Limitations of current screening tools

Given these profound impacts, early detection of perinatal mental health issues through routine screening, using tools such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)51 and the PBQ8 or MIBS,9 has become standard practice in many healthcare systems.

However, these tools have important limitations. The EPDS, developed nearly 4 decades ago, has been criticized for outdated and occasionally confusing wording,26, 52 as well as for limited cultural adaptation prior to translation and validation in non-UK populations.53 Its inclusion of anxiety-related items, while useful for identifying anxiety, can blur distinctions between depression, anxiety and trauma.54 These concerns have prompted calls for updated, multidimensional screening tools that assess depression, anxiety and trauma as distinct but related constructs.

Similarly, the MIBS, despite its widespread use, has been criticized for the absence of validated cutoff thresholds, partly due to methodological limitations.55 Recent studies have begun refining this measure, contributing to the development of more reliable tools for assessing perinatal mental health difficulties.

Toward tailored and integrated interventions

Encouragingly, effective treatment of perinatal depression has been shown not only to prevent its progression to chronic depression but also to improve mother–infant interactions and enhance infants’ cognitive and emotional development.56–58

The most promising strategies appear to be integrated interventions addressing maternal depression, bonding, and parenting simultaneously.59, 60 Yet in practice, treatment remains fragmented: cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the standard for depression,61 while bonding-focused approaches remain in the pilot stages.62

Future research should aim to develop comprehensive, multimodal models that integrate psychotherapy with lifestyle and psychosocial components, such as physical activity,63, 64 nature-based interventions,65, 66 and positive psychological techniques like positive memory recall.67, 68 These modalities can be further enhanced through the integration of wearable technologies, advanced sensors and video- or artificial intelligence-powered applications.69, 70

These approaches can enhance maternal and infant well-being within a preventive, family-centered framework.71, 72 Moreover, given their distinct mechanisms of action, combining them may produce synergistic effects that foster sustainable behavioral and emotional changes extending beyond the period of active treatment.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.