Abstract

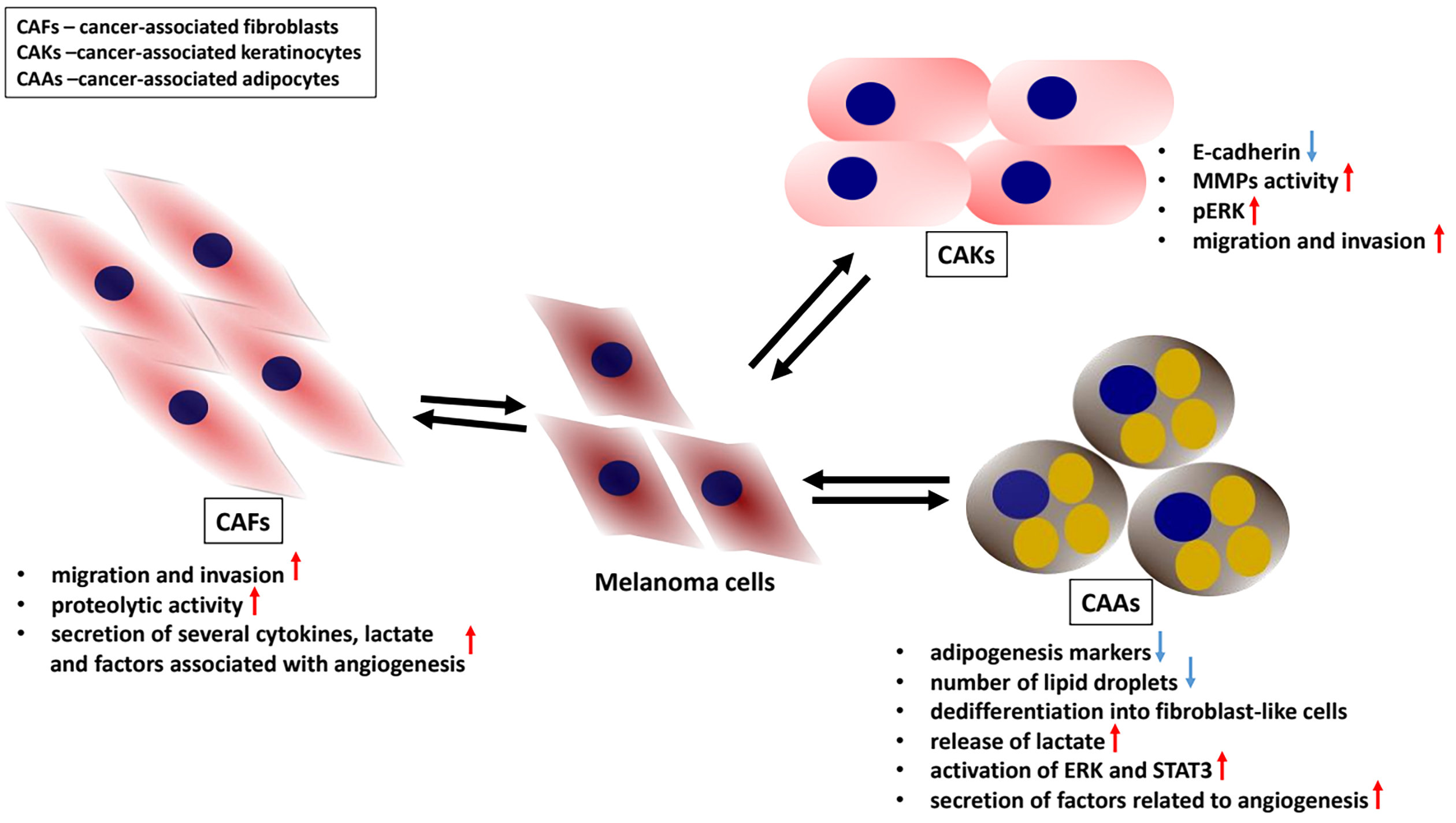

Today, it is well established that the tumor microenvironment (TME), the tumor niche, along with melanoma cells, plays a crucial role in cancer dissemination and influences the effectiveness of anticancer therapies. Therefore, it may serve as a potential therapeutic target in melanoma treatment. In our research, we focused on the effects exerted by cells within the melanoma microenvironment on cancer progression and the development of therapy resistance. Specifically, we examined stromal cells accompanying melanoma cells in the tumor – cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), cancer-associated keratinocytes (CAKs), and cancer-associated adipocytes (CAAs). Particular attention was given to keratinocytes, as their role in the melanoma microenvironment remains the least understood.

Key words: melanoma, drug resistance, stromal cells, microenvironment, signaling pathways

Introduction

Melanoma originates from pigment-producing cells, melanocytes, and is characterized by the highest mortality rate among skin cancers. One of the most significant risk factors for melanoma is prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. In healthy skin, melanocytes interact with keratinocytes and other neighboring cells to protect DNA from UV-induced damage, primarily through melanin-dependent mechanisms.1

Mutations in genes encoding proteins associated with the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, such as serine/threonine-protein kinase B-Raf (BRAF) and NRAS, account for approx. 70% of genetic aberrations induced by UV irradiation.2 A mutation in the BRAF gene (BRAF V600E) occurs in about 50% of melanoma patients and results in a constitutively active kinase.3, 4 Several targeted therapies against melanoma-specific molecular markers, including mutated BRAF, are currently used in clinical practice. Nevertheless, resistance to these drugs often develops rapidly in treated patients.5, 6 For all patients with invasive cutaneous melanoma, surgical excision of the primary tumor with 1–2 cm margins remains the standard of oncologic management. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended for patients with T1b or more advanced melanoma (tumor thickness >0.8 mm or any tumor with ulceration).7 In patients with sentinel lymph node micrometastasis, complete lymph node dissection (CLND) is no longer performed, based on the findings of the DeCOG and MSLT-II clinical trials.8 Instead of extensive surgical intervention, systemic adjuvant therapy has proven more effective in improving disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). High-risk stage IIB/C melanoma (T3b–T4b tumors with negative SLNB) is currently also an indication for 1 year of adjuvant immunotherapy with pembrolizumab or nivolumab (anti–PD-1 agents).9, 10 In patients with clinically detected metastatic lymph nodes or skin in-transit metastases (resectable stage III), the standard of care includes therapeutic lymph node dissection (TLND) or resection of in-transit tumors, followed by 1 year of adjuvant systemic treatment with either targeted therapy (dabrafenib and trametinib – BRAF/MEK inhibitors) or immunotherapy (pembrolizumab or nivolumab – anti–PD-1). New systemic adjuvant therapies improve OS and relapse-free survival (RFS) by approx. 20%.11, 12, 13

Before the advent of immunotherapies and targeted therapies, chemotherapy was the only treatment option for patients with stage IV melanoma (disseminated disease) and was associated with very poor outcomes. Today, it is used only in patients who are resistant to modern systemic treatments.14 For patients with unresectable stage III melanoma (metastatic lymph nodes or skin metastases) or stage IV disease, several systemic treatment options are available, similar to those used in the adjuvant setting. In BRAF-mutated patients, either immunotherapy or targeted therapy may be employed, whereas in BRAF wild-type patients, immunotherapy remains the standard of care. The combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab has demonstrated superiority over either agent used as monotherapy, providing a durable survival benefit in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) and melanoma-specific survival (MSS).15, 16 Radiotherapy may also be effective for melanoma patients with bone or brain metastases, although its use is limited to palliative settings.17, 18

Among the factors influencing the effectiveness of anticancer therapy is the tumor microenvironment (TME). Solid tumors are composed not only of malignant cells but also of various nonmalignant components within the tumor niche, including keratinocytes, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), immune cells, and adipocytes.19, 20 Additional elements, such as the composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and physical factors like hypoxia, must also be considered.21, 22, 23 The TME exerts diverse effects on melanoma progression and the development of therapy resistance. Initially, the TME may act as a physical barrier that limits drug delivery to cancer cells.24 In addition, stromal cells within the melanoma TME can promote tumor growth and enhance its invasive and angiogenic potential through paracrine signaling. These cells secrete growth factors, cytokines and chemokines that influence not only neighboring cells within the niche but also distant sites in the body.25 Moreover, they produce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which degrade ECM components, thereby creating pathways that facilitate cancer cell invasion through surrounding tissues.26 Cells within the TME can also secrete high-energy metabolites that are subsequently utilized by melanoma cells.27 Finally, immune cells, while initially contributing to the elimination of malignantly transformed cells, begin, during tumor progression, to facilitate immune evasion by melanoma cells. This occurs through various mechanisms, including the secretion of proinflammatory factors, expression of inhibitory receptors and induction of pro-tumor immune cell phenotypes.20

In our research, we focused on the effects of cells present in the melanoma microenvironment on cancer progression and the development of therapy resistance. In particular, we examined stromal cells accompanying melanoma cells in the tumor: CAFs, CAKs and CAAs. Special attention was given to keratinocytes, as their role in the melanoma microenvironment remains the least understood.

Keratinocytes play a protective role toward melanocytes in healthy skin; however, their interactions with cancer cells following melanomagenesis remain poorly understood. Under physiological conditions, keratinocytes regulate melanocyte proliferation through paracrine signaling and direct interactions mediated by E-cadherin-dependent cell–cell adhesion.19, 28 During melanoma development, E-cadherin expression decreases, while N-cadherin expression increases, leading to the loss of keratinocyte-mediated control over melanocytes. As a result, melanocytes begin to interact with N-cadherin-expressing cells such as fibroblasts.16

The cadherin switch is regulated by transcription factors involved in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), such as Snail, Twist and Slug, and may contribute to melanoma tumorigenesis.29 Moreover, Hsu et al. demonstrated that restoring E-cadherin expression in melanoma cells reestablishes their connection with keratinocytes, thereby reducing melanoma cell growth.30 In addition, keratinocytes exposed to UV radiation activate DNA repair pathways in melanocytes through the secretion of endothelin-1 (End-1) and α-melanocortin, thereby inhibiting melanocyte transformation into melanoma.31 Conversely, some studies suggest a pro-tumorigenic influence of keratinocytes on melanoma cells. It has been demonstrated that endothelin-1 secreted by keratinocytes activates caspase-8, which transiently binds to the E-cadherin/catenin complex in melanoma cells, leading to reduced E-cadherin expression and enhanced cancer cell invasion.32 Furthermore, extracellular End-1 has been shown to stimulate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation in melanoma cells treated with BRAF inhibitors. Moreover, End-1 expression is influenced by the level of melanocyte-inducing transcription factor (MITF). Overexpression of MITF enhances End-1 production, whereas its depletion is associated with End-1 downregulation. Furthermore, inhibition of endothelin receptor B increases the sensitivity of BRAF inhibitor-resistant melanoma cells to treatment.19, 33 Additionally, under the influence of fibroblast-derived keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), keratinocytes secrete the c-KIT ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), which subsequently activates the protein kinase B (AKT) and MAPK pathways, regulating cancer cell invasion and proliferation.34 Reports on the effects of melanoma on keratinocytes are scarce. One such study demonstrated alterations in the levels of intermediate filament proteins – cytokeratins – associated with the differentiation status of keratinocytes.35, 36 Cytokeratin 10 (CK10) is expressed in suprabasal keratinocytes undergoing cornification and desquamation, whereas cytokeratin 14 (CK14) is highly expressed in rapidly proliferating basal keratinocytes. Kodet et al. demonstrated that melanoma cells alter cytokeratin expression profiles in keratinocytes, leading to upregulation of CK14 and downregulation of CK10.37 Our findings indicate that keratinocytes activated through indirect co-culture with melanoma cells or incubation with melanoma-conditioned medium exhibit characteristics of less differentiated cells, including decreased CK10 expression, and show a preference for interacting with cancer cells rather than with other keratinocytes, likely due to reduced E-cadherin levels. Activated keratinocytes secrete a wide range of proteases, several of which, such as matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3), were first identified by our group as components of the activated keratinocyte secretome. These keratinocytes display high proteolytic activity, characterized by increased activity of MMP9 and MMP14 and decreased expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). They also exhibit elevated ERK activity and increased levels of MMP expression regulators, including runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and galectin-3. Furthermore, cancer-associated keratinocytes (CAKs) demonstrate enhanced migratory and invasive abilities following co-culture with melanoma cells in Transwell assays.37

Fibroblasts represent the most abundant cell population within the melanoma niche, comprising up to 80% of the tumor mass.38 In our study, we utilized 4 melanoma cell lines differing in invasiveness: 2 derived from primary tumors (WM1341D and A375) and 2 from lymph node metastases (WM9 and Hs294T). Importantly, when comparing the effects of these melanoma cells on fibroblast characteristics, we considered both their origin and invasive potential. An earlier study by Makowiecka et al.39 demonstrated that A375, WM9 and Hs294T cells exhibit higher rates of migration, invasion and proteolytic activity, as well as greater invadopodia formation, compared with WM1341D cells. Therefore, we classified the WM1341D cell line as less aggressive, while A375, WM9 and Hs294T were considered highly aggressive melanoma cell lines. We observed that fibroblasts co-cultured with melanoma cells exhibited increased motility, enhanced proteolytic activity and elevated secretion of several cytokines, lactate and angiogenesis-related proteins. The observed alterations in CAF biology were primarily induced by the highly aggressive melanoma cell lines (A375, WM9 and Hs294T), rather than by the less aggressive WM1341D line.40 These CAF-associated features can promote melanoma invasion and contribute to angiogenesis, inflammation and acidification of the TME. Adipocytes, another cellular component of the melanoma niche, are located in the deepest layer of the skin. The interactions between adipocytes and melanoma cells remain poorly understood, and the influence of obesity on melanoma progression is still controversial.41 Cancer-associated adipocytes (CAAs) were obtained by differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes into mature adipocytes according to the protocol described by Zebisch et al.42 Subsequently, mature adipocytes were co-cultured with melanoma cells using Transwell inserts. The transformation of adipocytes into CAAs was evaluated based on the expression of markers characteristic of differentiated adipocytes, which are typically reduced in CAAs. We also observed that melanoma-associated adipocytes exhibited decreased levels of adipogenesis markers and a reduced number of lipid droplets. Moreover, we observed that adipocytes exposed to melanoma cells undergo dedifferentiation into fibroblast-like cells. Cancer-associated adipocytes also exhibited significantly increased lactate release and upregulated expression of transporters for lactate, H+ ions and glucose, likely reflecting substantial metabolic reprogramming within the TME. The secreted lactate may serve as an energy source for melanoma cells, thereby promoting their proliferation. Concurrently, CAAs showed enhanced activation of specific signaling pathways, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), along with decreased secretion of angiogenesis-related factors.43

Conclusions

In the past, cancer cells were considered the sole target of anticancer therapy. Today, it is well recognized that cells within the tumor niche also play a crucial role in cancer dissemination. These cells influence cancer behavior both through paracrine signaling and direct cell–cell interactions. Notably, all of the described cell types contribute to the development of drug resistance and may therefore represent potential therapeutic targets in melanoma treatment.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.