Abstract

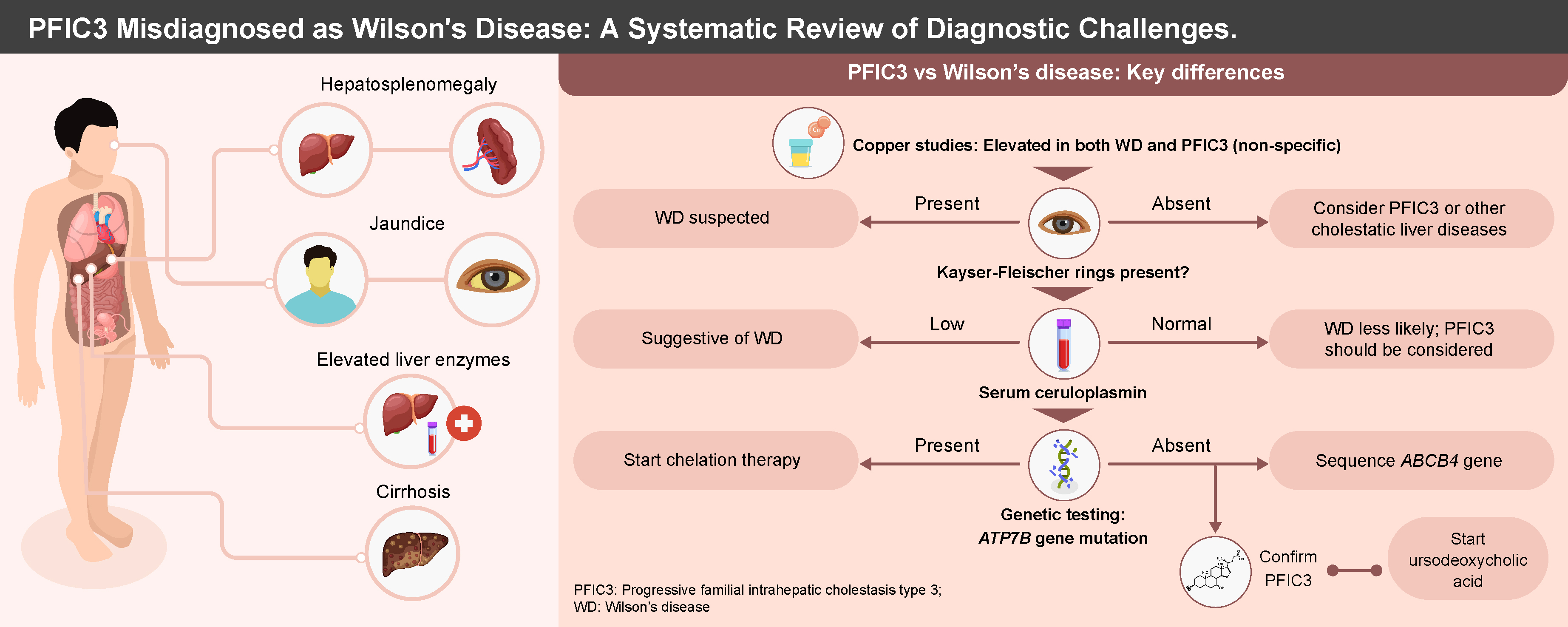

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3 (PFIC3) is a rare liver disorder caused by biallelic mutations in the ABCB4 gene, leading to multidrug resistance protein 3 (MDR3) deficiency. PFIC3 often presents with clinical and biochemical features that overlap with Wilson’s disease (WD), including hepatic copper accumulation and elevated urinary copper excretion. These similarities contribute to frequent misdiagnosis, resulting in inappropriate chelation therapy and delayed appropriate management. This systematic review examines reported cases of PFIC3 initially misdiagnosed as WD to highlight diagnostic challenges and assess patient outcomes. A comprehensive search across PubMed, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar identified 11 eligible studies involving 16 patients. Most cases were first treated as WD, receiving chelation therapy without clinical improvement. Diagnosis was later revised to PFIC3 following negative ATP7B mutation testing and identification of ABCB4 variants, often via whole-genome sequencing. Upon switching to ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), most patients experienced clinical stabilization. The findings underscore the need for heightened awareness of PFIC3 as a differential diagnosis in atypical WD cases, especially when ceruloplasmin is normal and Kayser–Fleischer (KF) rings are absent. Early genetic testing is essential to avoid mismanagement. Further observational studies are warranted to estimate misdiagnosis frequency and guide diagnostic protocols.

Key words: progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3, Wilson disease, misdiagnosis, genetic testing, ABCB4 gene

Introduction

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3 (PFIC3) represents the most severe phenotype associated with multidrug resistance protein 3 (MDR3) deficiency.1, 2 This condition arises due to biallelic pathogenic variations in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 4 (ABCB4) gene.3 Patients typically exhibit symptoms such as hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, discolored stools, and a history of pruritus.4 In the majority of cases, the disease advances to portal hypertension, cirrhosis and liver failure within the first 2 decades of life.5 The management of PFIC3 primarily involves the administration of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), which is the current first-line treatment. Ursodeoxycholic acid therapy has demonstrated efficacy in ameliorating symptoms in PFIC3 patients and improving liver function.6 This diagnostic overlap has substantial clinical implications, as inappropriate chelation therapy not only fails to halt disease progression but can also contribute to unnecessary treatment-related adverse effects and delayed liver transplantation.

A notable characteristic of PFIC3 is the disruption of copper metabolism secondary to intrahepatic cholestasis, as indicated by elevated hepatic and urinary copper levels. The elevated copper levels in PFIC3 lead to the mimicry of other diseases of impaired copper metabolism, such as Wilson’s disease (WD). Wilson’s disease is a rare autosomal recessive copper metabolism disorder caused by pathogenic mutations in the copper transporter gene ATP7B. According to the Leipzig diagnostic criteria for WD presented in Supplementary Table 2, patients are diagnosed with WD if they have a score ≥2. However, most PFIC3 patients also meet these requirements for WD, leading to some being misdiagnosed with WD.7 This misdiagnosis results in the administration of chelation therapy, to which PFIC3 patients do not respond, ultimately leading to disease progression and deterioration of liver function over time.7 Therefore, we conducted a systematic review to examine current reports of PFIC3 cases mimicking WD, identify diagnostic challenges and assess patient outcomes.

Objectives

The primary objectives of this systematic review are: 1) to examine current reports of PFIC3 cases mimicking WD; 2) to identify diagnostic challenges in differentiating PFIC3 from WD; and 3) to assess patient outcomes in cases of PFIC3 initially misdiagnosed as WD.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

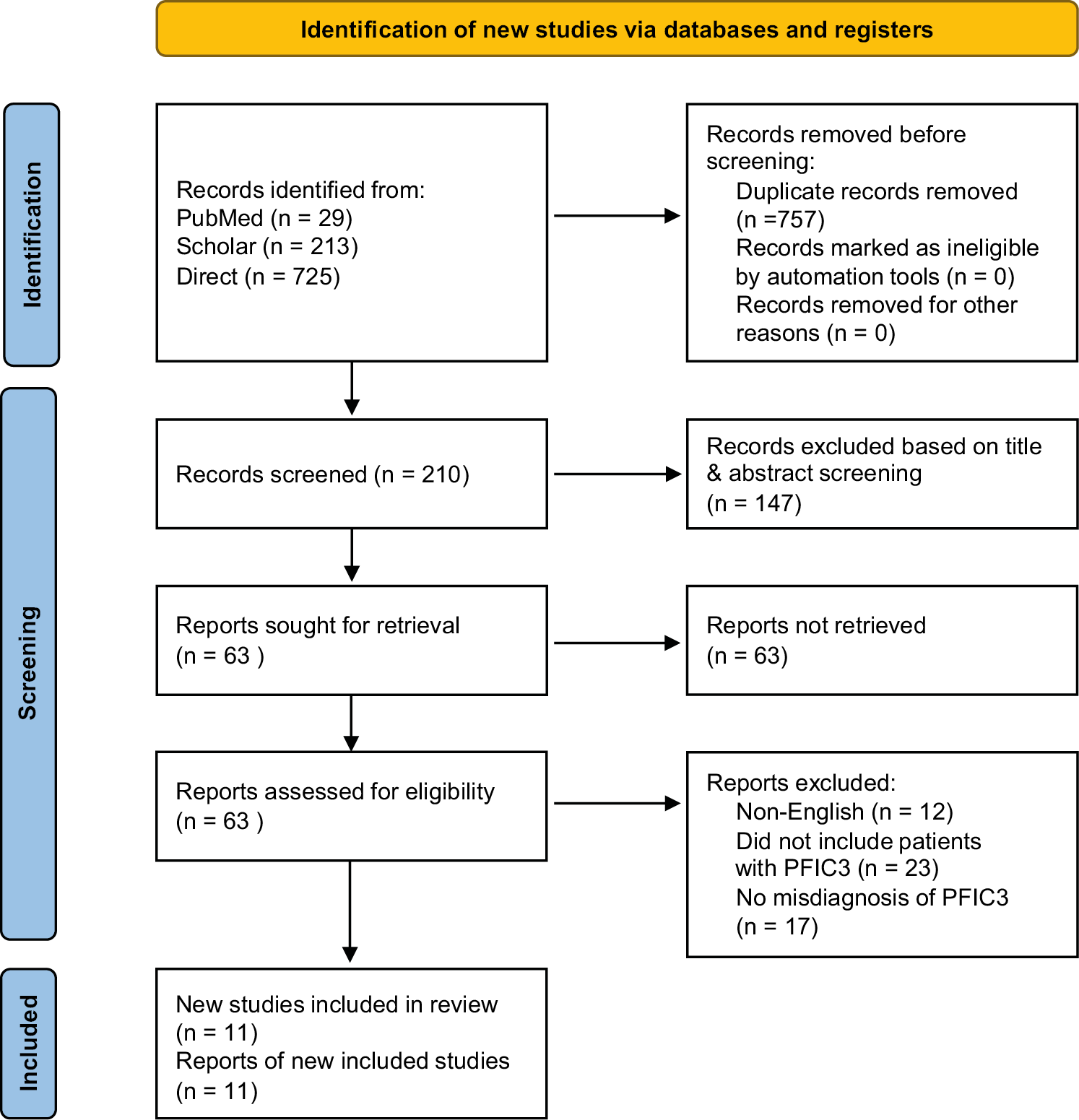

The methodology employed in this review conformed to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses).8 This study has been registered in PROSPERO with registration No. CRD420251065032.

Literature search

Two independent authors conducted an extensive literature review for pertinent articles up to May 2025. The initial strategy employed a specified search criterion across 3 databases: PubMed, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar. Boolean expressions were utilized to combine keywords for the electronic search (progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis OR PFIC3 OR ABCB4 disease OR MDR3 deficiency) AND (mimicking OR misdiagnosed). Following the completion of the database search, the reviewers manually examined the references of the identified studies to locate additional relevant studies.

Eligibility criteria

Following the retrieval of studies from the databases, each study was evaluated against a predetermined set of eligibility criteria prior to inclusion in the review. A study was incorporated into the review upon satisfying the following inclusion criteria: studies involving patients with PFIC3 presenting as WD, and studies designed as case reports, case series or observational studies.

The exclusion criteria for the review were applied to omit studies that did not meet the following conditions: 1) studies published in languages other than English; 2) studies that did not include patients with PFIC3; 3) studies that did not involve patients with a misdiagnosis or potential misdiagnosis of PFIC3 as WD; and 4) secondary studies such as narrative reviews, meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently performed the data extraction for this review. In instances where consensus was not initially achieved during the data extraction process, the reviewers engaged in discussions to resolve any discrepancies until agreement was reached. In accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, the authors examined all references obtained through various phases prior to data extraction. The initial phases involved screening abstracts to assess the relevance of the articles, leading to the elimination of irrelevant articles. Subsequently, the remaining articles were retrieved and evaluated to determine their eligibility. All studies meeting the eligibility criteria were included in the review, and their data were extracted. The information obtained from each article encompassed the authors, participants’ age and sex, initial presentation, initial laboratory investigations, first diagnosis and management regimen, response to the initial regimen, point of diagnosis change, alteration in management therapy, and patient outcomes.

Quality assessment

We employed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklists for case series and case reports to evaluate their methodological quality.9, 10 Subsequently, the results of the methodological quality assessment were presented in tabular form. Although formal metrics for inter-rater reliability were not computed, any differences were addressed through discussion until agreement was reached, adhering to the standards of qualitative synthesis.

Results

Search results

A comprehensive search across the databases yielded 967 references. After identifying and removing 757 duplicates, 210 references remained for relevance assessment. Of these, 147 abstracts were excluded due to irrelevance to the study. Subsequently, 63 articles were retrieved and evaluated against the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the review. Ultimately, 11 studies were included, having met the inclusion criteria. The remaining articles were excluded based on the following criteria: 12 were not published in English, 23 did not involve patients with PFIC3 and 17 did not address a misdiagnosis of PFIC3 as WD. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA diagram, which summarizes the search strategy.

Characteristics of the included studies

This review encompasses 11 studies, of which 9 are case reports11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 2 are case series.20, 21 These studies present evidence from 16 patients diagnosed with PFIC3, who initially presented as WD and were predominantly diagnosed and treated as such. The cohort consisted of 8 males, 5 females and 1 individual whose sex was not reported. The age of the participants across the studies was normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test, W = 0.918, p = 0.206), and is presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (19 ±12 years). A summary of the characteristics of all patients is provided in Table 1.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21

Methodological quality

Most of the included case reports demonstrated high methodological quality and comprehensively reported all relevant information regarding the treatment and diagnosis of PFIC3 in the included patients. However, a few studies did not adequately document the patients’ medical histories, while others failed to report the interventions administered following the diagnosis of PFIC3. A complete summary of the methodological quality is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes case reports concerning the diagnostic challenges associated with PFIC3. The studies included in this review highlight that both the failure to diagnose PFIC3 and its misdiagnosis as WD result in significant long-term consequences, as chelation therapy proves ineffective, leading to a progressive deterioration of liver function in patients.20, 21 Consequently, it is imperative to identify common diagnostic pitfalls to facilitate the differentiation between these 2 conditions. We also present a summary of the differences identified in the features of PFIC3 and WD, which can aid in differential diagnosis (Supplementary Table 3).

Presentation of PFIC3 patients

The typical age of symptom onset in these patients is within the first 2 decades of life.18 The earliest reported presentation occurs at 2 years of age, with the latest initial presentation occurring during the teenage years.18 Common symptoms among these patients include elevated liver indices, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, increased liver copper levels, elevated urinary copper excretion, and evidence of cirrhosis upon liver biopsy.16, 17 Unlike in WD, these patients do not exhibit Kayser–Fleischer (KF) rings upon ophthalmic examination.17, 18, 22 Additionally, their ceruloplasmin levels are typically normal.16, 22 The presentation of impaired copper metabolism and accumulation often leads to the consideration of WD as the likely etiology of the observed liver disease in these patients.23 Patients with PFIC3 also do not typically present with neurologic symptoms, unlike WD patients. Pathognomonic signs, especially in the putamen and globus pallidus, are common findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in WD patients.24

A distinguishing feature in the presentation of these patients is the absence of mutations in the ATP7B gene upon complete genome sequencing.18, 21 In most cases, ruling out WD due to the absence of this mutation prompts consideration of PFIC3 as a differential diagnosis, thereby reducing the likelihood of misdiagnosis.16, 20 Furthermore, the lack of ATP7B mutations often leads to further sequencing of the ABCB4 gene, revealing mutations that confirm the diagnosis of PFIC3.20 It is important to note that testing for MDR3 deficiency in biopsy specimens or explant samples may not yield conclusive results.17 For example, Bansal and Rastogi reported negative findings for MDR3 deficiency in tissue samples, only to identify the mutation through whole-genome sequencing.17 Therefore, whole-genome sequencing is recommended in cases of suspected PFIC3. Another distinguishing feature of these 2 conditions is the etiology of copper accumulation. In WD, copper accumulation is primarily due to impairment in copper transport, while in PFIC3, the cause of copper accumulation is cholestasis in most cases. Radiocopper testing, which typically relies on liver metabolism and transport of copper, is therefore a good diagnostic test for differentiating these 2 diseases. However, its use in the WD and PFIC3 diagnostic pitfalls is yet to be demonstrated.25

Management of PFIC3 in the context of misdiagnosis

In all included studies, the initial diagnosis of WD resulted in patients being placed on chelation therapy with either penicillamine, trientine or zinc.16, 19, 20 However, evidence suggests that these patients do not benefit from chelation therapy, and liver function continues to deteriorate during the treatment period.16, 20 In some instances, this deterioration necessitates liver transplantation.11, 12, 17 However, once PFIC3 is diagnosed and management is adjusted to UDCA at an initial dose of 20 mg/kg/day, most patients experience stable liver function, and the liver disease does not progress.19, 20 While liver transplantation remains the definitive treatment for PFIC3, failure to diagnose PFIC3 can still lead to worsening liver function, as reported by Bansal and Rastogi, where a patient’s liver indices became deranged 4 months post-liver transplantation. However, following the management change to UDCA, the patient responded well to treatment.17

Limitations of the study

This systematic review employed a comprehensive search strategy to examine all studies reporting PFIC3 presenting as WD. Nevertheless, the study encountered certain limitations. Primarily, we included only case reports, which suggests that these occurrences are rare. Consequently, while the findings may enhance awareness regarding the potential misdiagnosis of PFIC3, they cannot be generalized to the broader population. Furthermore, the exclusive reliance on case reports resulted in a minimal sample size from which our data were derived. The total sample size of 16 patients across 11 studies is quite small. Additionally, there is limited information provided on how data extraction and quality assessment were conducted – e.g., no formal metrics for inter-rater reliability are reported. The methodological quality assessment using JBI checklists is mentioned but details are lacking on how this was applied. There is also no formal synthesis or meta-analysis of data across studies due to the nature of the included reports. Finally, potential publication bias is not addressed, as case reports of successful diagnoses may be more likely to be published than misdiagnoses that were not eventually corrected.

Conclusions

Evidence synthesized from the included studies indicates that PFIC3 can manifest with symptoms resembling those of WD, potentially leading to misdiagnosis. It is important for clinicians to recognize that patients with PFIC3 do not exhibit KF rings upon slit lamp examination and typically present with normal ceruloplasmin levels. Consequently, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of the ATP7B and ABCB4 genes should be conducted to distinguish between WD and PFIC3. Furthermore, additional retrospective observational studies are warranted to ascertain the frequency with which PFIC3 is misdiagnosed as WD. This will facilitate the identification of diagnostic challenges and contribute to the development of diagnostic guidelines and protocols. Moreover, prospective studies should be undertaken to evaluate whether dual genetic testing for ATP7B and ABCB4 gene mutations yields beneficial outcomes in the management of patients with either WD or PFIC3.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17242238. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. A JBI checklist summarizing the methodological quality of the included case reports.

Supplementary Table 2. Leipzig criteria for WD diagnosis.

Supplementary Table 3. Differences in the presentation of WD and PFIC3.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.