Abstract

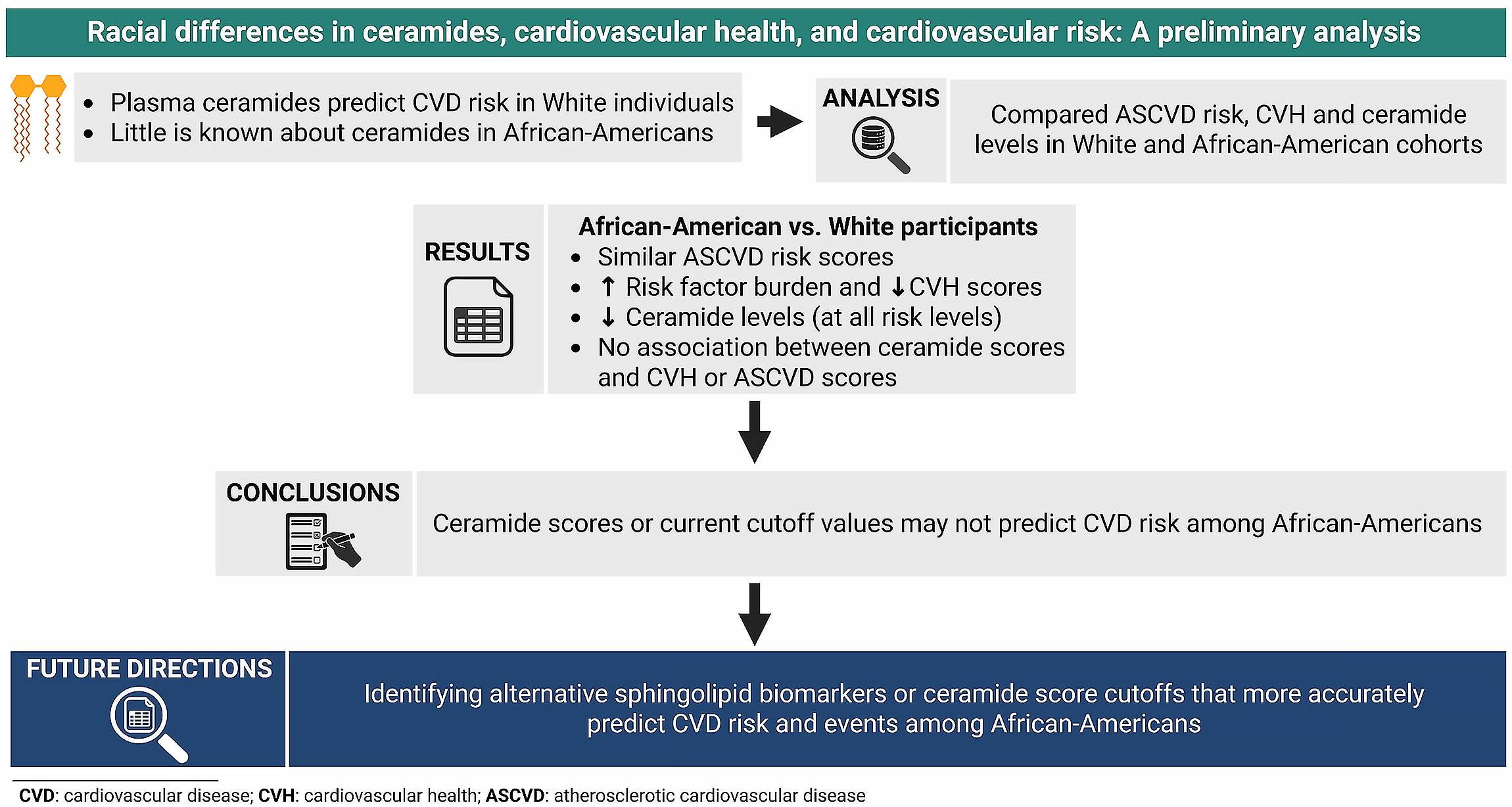

Background. Plasma ceramides are recognized biomarkers of cardiovascular risk; however, racial and ethnic differences in their levels, as well as their association with cardiovascular health (CVH) among African-American populations, remain insufficiently studied.

Objectives. This study aimed to assess the association between ceramide scores and CVH, as well as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk, among African-American adults, and to compare ceramide scores between African-American and White adults.

Materials and methods. We conducted a secondary analysis of 2 U.S. studies including African-American and White adults. Collected data encompassed demographics, behavioral factors (e.g., diet) and clinical measures (e.g., plasma ceramide levels). Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk was assessed using the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 10-year pooled cohort equations, while CVH was evaluated using the American Heart Association (AHA) Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) scoring system.

Results. Fifty-eight African-American adults (mean age: 54.6 years; 67.2% women) and 1,103 White adults (mean age: 64.5 years; 52.1% women) were included. Compared with White participants, African-Americans had significantly higher prevalence of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, but similar ASCVD risk (12.8% vs 12.6%; p = 0.65). No significant associations were observed between ceramide scores and either LE8 or ASCVD risk in African-Americans. Ceramide levels differed by race/ethnicity, with African-Americans showing lower concentrations of 18:0 (0.08 vs 0.10 μmol/L) and 24:1 (0.91 vs 1.17 μmol/L) species compared with White adults (both p < 0.001).

Conclusions. No association was observed between ceramide scores and CVH or ASCVD risk in African-American adults. Despite having a less favorable cardiometabolic profile, African-Americans exhibited lower ceramide levels than White adults. These findings suggest that ceramide scores may not accurately reflect cardiovascular risk in African-American populations.

Key words: African-American, biomarkers, cardiovascular disease, ceramides, cardiovascular risk assessment

Background

Although cardiovascular care has advanced, African-American adults continue to experience suboptimal cardiovascular disease outcomes compared to White adults.1 Furthermore, while African-American adults typically exhibit higher levels of established biomarkers such as lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) than White adults, the strength of the association between Lp(a) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) appears to be comparable across both groups.2

This evidence underscores the need to explore novel biomarkers that may enhance cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment among African-American adults. Ceramides are phospholipids that play key roles in cellular functions, and some ceramide species have been associated with atherosclerotic plaque instability and adverse cardiovascular events.3, 4

Research has demonstrated that elevated plasma ceramide species, including ceramide (d18:1/16:0), (d18:1/18:0), (d18:1/20:0), and (d18:1/24:1), are independent predictors of CVD risk.5 These findings underscore the utility of ceramides in CVD risk assessment, even among individuals with normal lipid profiles or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations below conventional treatment thresholds.4, 5 Importantly, ceramide-based risk scores have been developed for clinical application, providing efficient tools for CVD risk stratification and prevention.4, 6 However, racial and ethnic variations in ceramide concentrations, as well as their relationship to cardiovascular health (CVH) in African-American populations, remain insufficiently explored.

Objectives

This study aimed to examine the association between ceramide scores and both CVH and ASCVD risk among African-American adults, and to assess differences in ceramide profiles between African-American and White adults.

Materials and methods

A secondary analysis was performed using data from 2 U.S. studies in Minnesota: The Fostering African-American Improvement in Total Health! (FAITH!) Heart Health+7 study, a community-based study of Black/African-American adults, and the Prevalence of Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Dysfunction (PAVD) study,6 a community population-based cohort of predominantly White adults. Ethical approval for both studies was granted by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 21-011103 (Heart Health+) and 15-005100 (PAVD)). All participants provided informed consent before enrollment. Data included demographic characteristics, behavioral factors (e.g., dietary patterns) and clinical measures (e.g., ceramide 16:0, 18:0, 24:0, and 24:1 levels). Ceramide ratios 16:0/24:0, 18:0/24:0 and 24:1/24:0 were obtained. Ceramide scores were calculated on a 12-point scale and categorized into risk levels: low (0–2), intermediate (3–6), moderate (7–9), and high (10–12). The ASCVD risk was assessed using the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 10-year pooled cohort risk scores, while CVH was calculated using AHA Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) scores.

Continuous variables, including age and mean ASCVD risk scores, were compared between the 2 study cohorts using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Pearson’s χ2 goodness of fit test was used to compare categorical variables, including categorized ASCVD risk score, sex and the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. Within the African-American cohort, Pearson’s correlation was used to assess associations between ceramide levels and both LE8 scores and ASCVD risk. Ceramide scores were compared between study groups using multivariable linear regression with robust standard errors (SEs), adjusting for age, sex and cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and tobacco use/cigarette smoking).

All statistical test assumptions were assessed. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using histograms when comparing mean values between White and African-American cohorts. Linearity between variables was examined for correlation analyses. The linear regression model was assessed for linearity, multicollinearity, homoscedasticity, and normality of residuals (see Supplementary data). Robust SEs were used in the model to provide robust estimates of the mean difference in ceramide scores between cohorts in the context of potential heteroscedasticity and non-normality of error residuals. Statistical significance was defined as a p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using R v. 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Fifty-eight African-American adults (mean age (standard deviation (SD): 54.6 (11.9) years, 67.2% women) and 1,103 White adults (mean age (SD): 64.5 (11.9) years, 52.1% women) were included (Table 1). The prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors was significantly higher among African-American adults than White participants: obesity (67.9% vs 31.9%; p < 0.001), hypertension (69.6% vs 41.2%; p < 0.001), diabetes (30.4% vs 11.1%; p < 0.001), and hyperlipidemia (42.9% vs 29.3%; p = 0.03). The mean ASCVD risk scores were comparable between African-American (12.8% (SD = 10.4)) and White individuals (12.6% (SD = 11.1)) (p = 0.65). White individuals had higher ceramide levels for 18:0 (0.10 (0.04) vs 0.08 (0.03) μmol/L) and 24:1 (1.17 (0.33) vs 0.91 (0.31) μmol/L) than African-American adults (p < 0.001). In the African-American study group, ceramide scores had a weak, nonsignificant association with LE8 scores (r = −0.29, p = 0.071) and ASCVD risk scores (r = −0.10, p = 0.503). White individuals showed higher ceramide scores than African-American adults (mean (SD): 3.48 (2.88) vs 1.90 (1.97), p = 0.001) in the adjusted model (Table 2).

Discussion

This study found no significant associations between ceramide profiles and CVH or ASCVD risk among African-Americans. Surprisingly, African-American adults had lower ceramide scores than White adults, despite having more adverse cardiometabolic risk factors. This finding aligns with the limited existing literature. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging found that African-American adults had lower plasma concentrations of most ceramide and dihydroceramide species compared to White adults.8 Similarly, Buie et al. reported that African-American individuals with metabolic disease had lower levels of ceramides C16 and C20 compared to White individuals.3 Additionally, total ceramide levels were higher in African-Americans without metabolic disease relative to those with metabolic disease. These findings suggest distinct expression of sphingolipids in African-Americans.

Clinical validation of ceramide scores has been conducted in White populations in the USA and Europe5, 6; thus, these findings may not be generalizable to African-Americans due to potential differences in genetic and lifestyle factors between these groups. Notably, African-Americans in this study exhibited lower LE8 scores for diet and body mass index (BMI), which, based on existing evidence on the association between adherence to a healthy diet and circulating ceramide levels, should have resulted in higher ceramide levels.9, 10 One explanation could be that ceramide levels are expressed differently in African-Americans than in White individuals. The postulation of genetic differences in sphingolipid expression and blood levels is supported by evidence of higher occurrences of mutations that lower other lipids such as LDL-C among African-Americans.11 Further genetic studies are warranted to determine whether African-Americans express ceramides differently.

These findings indicate that ceramide scores may have limited utility in assessing cardiovascular risk in African-American adults, potentially leading to suboptimal patient management and exacerbation of existing CVD disparities in this population. Thus, alternative sphingolipid biomarkers or ceramide score cutoffs should be explored. Buie et al.3 found that sphingosine-1-phosphate (Sph-1P) levels were notably higher in African-Americans than in White and African-American adults without metabolic disease. Given the observed inverse relationship between ceramide levels and cardiometabolic profiles in African-Americans, future research should investigate whether Sph-1P may serve as a more accurate biomarker of CVD risk in this population. Notably, Mielke et al. found that age-related elevations in ceramides were less pronounced among African-Americans. The observation that African-American adults in our study exhibited ASCVD risk levels comparable to those of the White cohort, despite being younger, underscores the need for further validation and investigation of ceramides as CVD biomarkers in African-American populations.

Limitations

While statistically significant differences in ceramide scores were observed between African-American and White participants, a notable limitation is the relatively small sample of African-American participants. This may have limited the ability to detect associations between ceramide profiles and CVH or ASCVD risk within this group, raising the possibility of type II error and the potential for missed meaningful associations. Larger, adequately powered studies are warranted to validate ceramide scores as CVD risk biomarkers or to identify alternative sphingolipid biomarkers to assess CVD risk among African-Americans. Additionally, due to differences in study design, behavioral metrics (diet, physical activity and sleep health) were not collected in the PAVD study,6 precluding an assessment of LE8 scores among White participants. Given these limitations, this heterogeneity should be considered when interpreting the comparative findings, and our results should be interpreted cautiously as exploratory.

Conclusions

While ceramide profiles are beneficial in predicting CVD risk in White populations, our study findings suggest that their utility in assessing risk among African-American adults appears limited. Identifying accurate population-specific biomarkers or ceramide score cutoffs is crucial for preventing CVD and improving health outcomes in high-risk populations such as African-Americans.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to an agreement with the FAITH! Heart Health+ study participants.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15756695. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. Scatterplot to assess linear relationship between LE8 score and ceramide score in the cohort of African-American adults.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Scatterplot to assess linear relationship between ASCVD score and ceramide score in the cohort of African-Americans adults.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Histogram to check normality assumption for age in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 4. Histogram to check normality assumption for ASCVD risk score in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Histogram to check normality assumption for ceramide 16_0 in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 6. Histogram to check normality assumption for ceramide 18_0 in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 7. Histogram to check normality assumption for ceramide 24_1 in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 8. Histogram to check normality assumption for ceramide ratio (16_0)_(24_0) in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 9. Histogram to check normality assumption for ceramide ratio (18_0)_(24_0) in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 10. Histogram to check normality assumption for ceramide ratio (24_1)_(24_0) in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 11. Scatterplot to assess the linear relationship between age and ceramide score in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 12. Plot of model residuals compared to fitted values to assess the validity of the linear regression model in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 13. Scale-location plot to assess homoscedasticity in the linear regression model in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Fig. 14. Q-Q plot to assess normality of residuals in the linear regression model in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.

Supplementary Table 1. Table of generalized variance inflation factor values to assess for multicollinearity in the cohorts of African-American and White adults.