Abstract

Bacterial pneumonia is a cause of HIV-associated morbidity and mortality. Recurrent pneumonia, defined as 2 or more episodes within a 12-month period, is an AIDS-defining illness. The prevalence of bacterial pulmonary infections in HIV-infected patients has been decreasing with the introduction and widespread use of antiretroviral therapy. In well-developed settings, the frequency of bacterial pneumonia in people living with HIV is comparable to that in the general population. Studies have shown that the cumulative incidence of pneumonia is higher in HIV-infected patients with advanced immunosuppression, airflow limitation, smoking, intravenous drug use, or in those from underdeveloped countries and urban areas. In HIV-infected patients with community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus species are the most frequently isolated pathogens. However, in untreated or poorly adherent HIV-infected individuals, opportunistic infections may occur. Although the incidence of opportunistic infections among HIV-infected patients has declined in well-developed settings due to the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy, tuberculosis remains a serious threat and a major cause of morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals worldwide. Early diagnosis of HIV infection, timely initiation of antiretroviral therapy with good adherence, and promotion of vaccination remain priorities. This editorial provides an overview of community-acquired pneumonia in HIV-infected patients and discusses recent changes in its epidemiology and etiology.

Key words: infection, HIV, community-acquired pneumonia

Introduction

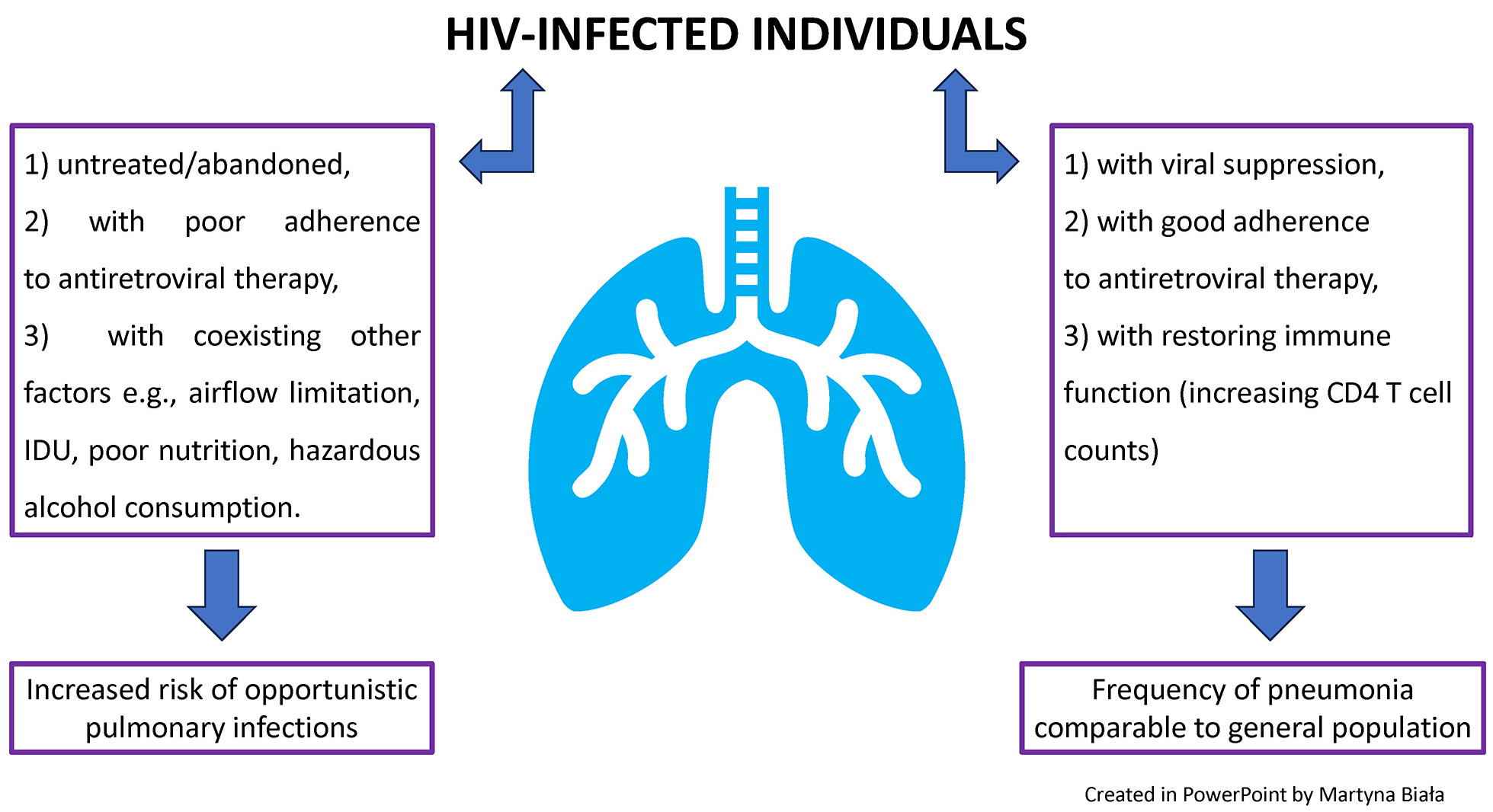

The prevalence of bacterial pulmonary infections in HIV-infected patients has decreased with the introduction and widespread use of antiretroviral therapy. In well-developed settings, the frequency of bacterial pneumonia among people living with HIV is now comparable to that in the general population.1

A study conducted in a Swiss cohort demonstrated that the incidence of bacterial pneumonia declined from 13.2 to 6.8 cases per 1,000 person-years between 2008 and 2018 in HIV-infected patients.2 Another study reported an incidence rate of pneumonia of 5.5 cases per 1,000 person-years among people living with HIV in Denmark.3 In comparison, in the French adult population, the estimated incidence rate of outpatient community-acquired pneumonia was 4.7 cases per 1,000 inhabitants, rising to 6.7 cases per 1,000 among individuals aged 65 years or older.4 The reported annual incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in industrialized countries ranges from 1.19 to 8.7 cases per 1,000 inhabitants in general practice.4

This editorial provides an overview of community-acquired pneumonia in HIV-infected adult patients and discusses recent changes in its epidemiology and etiology. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and UpToDate), including only peer-reviewed studies published in English.

Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in HIV-infected adults

The estimated global incidence of community-acquired pneumonia ranges from 1.5 to 14 cases per 1,000 person-years and is influenced by several factors, including geographical region, season, and population characteristics.5, 6 However, studies have shown that the cumulative incidence of pneumonia is higher among HIV-infected patients with advanced immunosuppression, airflow limitation, smoking habits, intravenous drug use, and among individuals from developing countries and urban areas.1, 3, 7

Lower CD4 counts have been associated with a higher risk of bacterial pneumonia in people living with HIV. Kohli et al. reported that the incidence rates of bacterial pneumonia in HIV-infected patients with CD4 T-cell counts >500, 200–500 and <200 cells/mm3 were 4.9, 8.7 and 17.9 cases per 100 patient-years, respectively.8 Another study found that individuals with CD4 T cell counts of 350–499 cells/mm3 were at a higher risk of bacterial pneumonia compared with those whose CD4 T cell counts exceeded 500 cells/mm3.2

Compared with uninfected individuals, people living with HIV are more likely to develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and to experience an earlier-than-expected decline in lung function.9 Factors contributing to these differences include higher smoking rates, chronic immune activation and inflammation, increased susceptibility to pulmonary infections associated with lower CD4 T-cell counts, accelerated aging, alterations in the lung and gut microbiome, and greater vulnerability to air pollution-related lung damage.9

Ronit et al. showed that HIV infection was independently associated with lower forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC).10 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung function abnormalities are linked to an increased rate of severe pneumonia in HIV-infected patients.9 Drummond et al. evaluated spirometry results in individuals with HIV and found that nearly 40% of them exhibited abnormal spirometric patterns.11 Airflow limitation was associated with a higher frequency of bacterial pneumonia and Pneumocystis jirovecii infection, as well as with smoking status and intensity, age, asthma diagnosis, and the presence of respiratory symptoms.11 Smoking is more common among individuals with HIV, and HIV-infected smokers are more susceptible to smoking-induced lung damage compared with their uninfected counterparts.9, 12, 13, 14

It is estimated that smoking is associated with a 2- to 5-fold greater risk of bacterial pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease in individuals with HIV.1 Intravenous drug users (IDUs) have a 10-fold higher risk of developing pneumonia compared to non-users.15 Among people living with HIV, bacterial pneumonia is more common in those who are IDUs.16

Intravenous drug users have a substantially higher risk of pneumonia due to immunosuppression, poor nutrition, homelessness, and an increased risk of aspiration. Moreover, alcohol consumption, hazardous drinking, and alcohol dependence are associated with greater pneumonia severity among HIV-infected individuals.17 A summary of risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in HIV-infected adults is presented in Table 1.

Epidemiology and etiologies of community-acquired pneumonia in HIV-infected patients

In people living with HIV who develop community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus species are the most frequently isolated pathogens, similar to those found in the general population.1, 18 Schleenvoigt et al. analyzed a German cohort with community-acquired pneumonia and found that S. pneumoniae was the most common pathogen isolated from both people living with HIV (21.3%) and the control group (17.2%), followed by Haemophilus influenzae (13.5% vs 12.6%, respectively).18

Interestingly, the same study found that Staphylococcus aureus was detected in 20.2% of samples from people living with HIV and in 19.2% of samples from the control group.18 However, distinguishing between S. aureus infection and colonization in this cohort was challenging, as positive sputum specimens and nasopharyngeal swabs were predominantly identified using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR).18

The 6-month mortality rate in the German cohort was significantly higher among people living with HIV (6.8%) than in the control group (1.4%), although the authors noted that the number of cases was lower than previously reported.18 The opportunistic pathogen P. jirovecii was detected only rarely.18 Another study demonstrated that S. pneumoniae and S. aureus are among the most common bacterial coinfections in hospitalized patients with influenza.19

Previous studies from the early antiretroviral therapy era demonstrated that the prevalence of community-acquired pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. aureus was higher among people living with HIV than among those without HIV infection.20, 21 Risk factors associated with P. aeruginosa pneumonia include poorly controlled HIV infection, low CD4 T-cell counts, neutropenia, immunosuppression, malnutrition, coexisting lung disease, corticosteroid use, hospitalization within the past 90 days, mechanical ventilation or intensive care unit (ICU) admission, prior antimicrobial exposure, residence in a healthcare facility or nursing home, burns, malignancy, hemodialysis, organ transplantation, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and the presence of invasive devices such as indwelling catheters or endotracheal tubes.22, 23

Risk factors for S. aureus infection include IDUs, open wounds or sores, prior antimicrobial exposure, hospitalization within the past 90 days, ICU admission, immunosuppression, colonization with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), invasive procedures, hemodialysis, corticosteroid use, residence in a healthcare facility or nursing home, diabetes mellitus, long-term central venous access or indwelling urinary catheter, and employment as a healthcare provider.23, 24, 25 Previous studies have also shown that community-acquired MRSA infections can be transmitted among men who have sex with men (MSM).26

Globally, MSM are at greater risk of acquiring HIV and represent the main group of people living with HIV in many countries. A described community-acquired outbreak of MRSA infection among MSM most commonly manifested as infections of the buttocks, genitals or perineum.26 However, skin and soft tissue infections caused by MRSA can progress to invasive diseases such as pneumonia and sepsis. Moreover, MRSA colonization is a known risk factor for the development of MRSA pneumonia, and studies have shown that MRSA nasal carriage and skin colonization occur more frequently in people living with HIV than in their seronegative counterparts.27, 28

Shet et al. indicated that cumulative prevalence of MRSA carriage was substantially higher in HIV-infected patients (16.8%) than among seronegative individuals (5.8%).27 However, little up-to-date data are available on MRSA and P. aeruginosa as etiologic agents of community-acquired pneumonia in people living with HIV. Community outbreaks of MRSA, usually harboring Panton–Valentine leukocidin and associated with high morbidity and mortality, appear to be relatively rare.

In HIV-infected individuals without additional risk factors for P. aeruginosa or S. aureus infection, antibiotic regimens provide broad coverage against MRSA and P. aeruginosa does not seem to be obligatory. The most common pathogens cause community-acquired pneumonia in HIV-infected individuals in well-developed settings are the same as in seronegative counterparts and the antibiotic regimens in HIV-infected patients are also the same as those without HIV.29

Compared with historical data, people living with HIV who have achieved virological suppression and maintain CD4 T-cell counts above 350 cells/mm3 are less likely to develop invasive pneumococcal disease. Moreover, they are now more likely to be vaccinated against S. pneumoniae.

Cillóniz et al. reported that people living with HIV who developed pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae were more likely to have been vaccinated against influenza (14% vs 2%) and pneumococcal disease (10% vs 1%) compared with HIV-negative individuals with pneumococcal pneumonia.30 Both groups (HIV-positive and HIV-negative) had similar rates of ICU admission (18% vs 27%), need for mechanical ventilation (12% vs 8%), length of hospital stay (7 days vs 7 days), and 30-day mortality (0%).30

These data indicate that the need for hospitalization and clinical outcomes of pneumococcal pneumonia in virologically suppressed people living with HIV who have CD4 T-cell counts above 350 cells/mm3 are similar to those in the general population.30 However, Mamani et al. reported a high incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease among people living with HIV with median CD4 T-cell counts below 350 cells/mm3 and found that alcoholism, hepatic cirrhosis and lower nadir CD4 T-cell count were associated with an increased risk of death.31 Moreover, the rate of vaccination against S. pneumoniae was low in this group.31 These findings emphasize that early diagnosis of HIV infection, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and promotion of vaccination remain priorities.

Atypical bacteria are intracellular organisms that are difficult to culture and not visible on Gram stain. The true incidence of pneumonia caused by atypical bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydophila spp. is unknown; however, these pathogens appear to be uncommon causes of community-acquired pneumonia in people living with HIV. In a Brazilian study examining the etiologic agents of community-acquired pulmonary infections in people living with HIV, M. pneumoniae was detected in 8% and Chlamydophila pneumoniae in 5% of cases.32 The majority of participants in this study had never used antiretroviral therapy, had discontinued treatment, or reported poor adherence. CD4 T-cell counts were available for 90% of these patients, and 73% had counts below 200 cells/mm3.32

It is worth noting that the diagnosis of atypical pneumonia is particularly challenging in people living with HIV with advanced immunosuppression and may often go unrecognized. Legionella spp. infection is infrequent and presents with a similar clinical course in people living with HIV and in seronegative individuals.33 Respiratory viruses have been detected by molecular methods in approx. 1/3 of the general adult population with community-acquired pneumonia. However, the extent to which viral respiratory pathogens act as single causative agents, cofactors in the progression of bacterial pneumonia or triggers of a dysregulated immune response remains unclear.29

Viruses are also frequently detected in people living with HIV, and some studies suggest that the mortality rate from influenza or COVID-19 may be higher in this population.34, 35 Furthermore, the prevalence of severe acute respiratory infections caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is higher among people living with HIV and among individuals aged 65 years or older.36

The prevalence of opportunistic pulmonary infections in people living with HIV has decreased with the use of antiretroviral therapy and varies across regions. Moreover, it depends on individual risk factors such as advanced immunosuppression related to HIV, malignancies, use of immunosuppressive agents, and long-term corticosteroid therapy. The incidence of P. jirovecii pneumonia has been significantly reduced by antiretroviral therapy and prophylaxis with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole.37

However, Figueiredo-Mello et al. reported that among 143 people living with HIV who were untreated, had discontinued therapy, or demonstrated poor adherence to antiretroviral treatment, P. jirovecii was the most frequently detected pathogen (36%), followed by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (20%).32 Another study conducted in Cape Town, South Africa, included 284 people living with HIV (64% women) and found that 148 had culture-confirmed tuberculosis (TB), 100 had community-acquired pneumonia, and 26 had P. jirovecii pneumonia.38

The median CD4 T-cell count in this cohort was 97 cells/mm3, and 38% of participants were receiving antiretroviral therapy.38 Aspergillosis can also occur in people living with HIV, and many of these cases are associated with high mortality.39

Although the incidence of opportunistic infections among people living with HIV has declined, particularly in well-developed countries, due to the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy, TB remains a serious threat and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.40 It is estimated that people living with HIV are 14 times more likely to develop TB and experience poorer treatment outcomes.40 Moreover, people living with HIV are at higher risk of developing multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB).41 In 2020 and 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic slowed global TB control efforts due to widespread disruptions in healthcare and TB diagnostic services. In Europe, TB is more common among migrants from regions with high TB incidence and among individuals affected by social determinants such as poverty and homelessness, with the disease burden remaining particularly high in Eastern Europe.42

Given the increased risk of TB in people living with HIV, TB should always be considered when assessing a patient’s medical history, potential exposure, risk factors, and chest X-ray findings. Establishing the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia is essential to ensure appropriate therapy and to prevent the overuse of antibiotics.

Moreover, people living with HIV who have low CD4 T-cell counts are at higher risk of developing polymicrobial pneumonia, defined as infection caused by more than one pathogen.43 Recent advances in microbiological diagnostics, particularly molecular techniques and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, have improved microorganism identification by reducing testing time and increasing sensitivity and specificity, thereby enabling faster, more accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment. However, interpretation of these results must always take the clinical context into account, as a positive test does not necessarily indicate an active infection.

Conclusions

In well-developed settings, the frequency of bacterial pneumonia among people living with HIV is comparable to that in the general population, and HIV infection alone does not appear to be a risk factor for increased mortality in community-acquired pneumonia, owing to effective antiretroviral therapy. However, in untreated individuals or those with poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy, opportunistic infections may still occur. Early diagnosis of HIV infection, timely initiation of antiretroviral therapy with good adherence, and promotion of vaccination remain key priorities.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.