Abstract

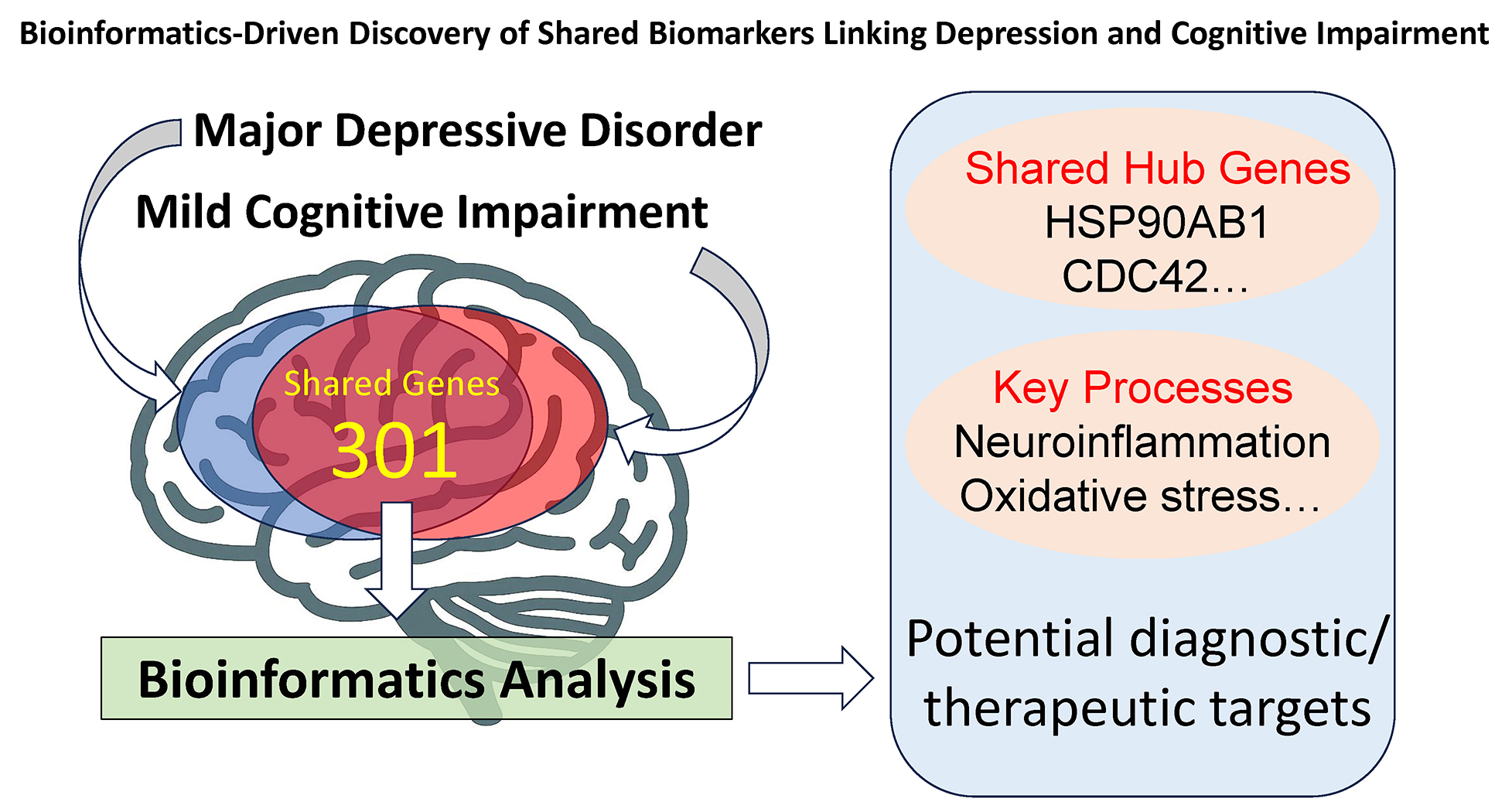

Background. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is frequently comorbid with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), yet its molecular basis remains unclear.

Objectives. This study aimed to identify shared differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and biological pathways that may underlie the comorbidity between MDD and MCI. Using integrative bioinformatics approaches applied to transcriptomic datasets, we sought to uncover molecular biomarkers that could inform early diagnosis and provide novel targets for mechanism-based therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods. Transcriptomic datasets from MDD (GSE58430) and MCI (GSE140831) patients were analyzed to identify DEGs. Functional enrichment analyses were performed using the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed to identify core genes.

Results. A total of 301 DEGs were shared between MDD and MCI. Gene Ontology and KEGG enrichment analyses revealed key biological processes involved in neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, synaptic dysfunction, and apoptotic signaling. The PPI network analysis identified nine hub genes with high connectivity: HSP90AB1, CDC42, NFKB1, CD8A, CALM3, PARP1, CD44, H2BC21, and MYH9.

Conclusions. These findings reveal shared molecular biomarkers and pathways linking MDD and MCI, providing insights into their comorbidity. The identified core genes, particularly PARP1 and CDC42, may serve as novel targets for early diagnosis and mechanism-based therapeutic strategies in psychiatry and neurodegenerative disorders.

Key words: biomarkers, bioinformatics, gene expression, major depressive disorder, mild cognitive impairment

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a prevalent mental health condition. According to a 2020 World Health Organization (WHO) report, approx. 280 million people worldwide suffer from MDD.1 It is not only a leading cause of emotional distress but is also frequently associated with cognitive impairments, including comorbidity with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Furthermore, individuals diagnosed with MCI are at an increased risk of developing depression. For instance, a meta-analysis of 57 studies involving 20,892 participants revealed that the overall pooled prevalence of depression in patients with MCI was 32%.2 This highlights the substantial overlap between these 2 disorders.3

Clinically, there is a strong correlation between MDD and MCI. Studies have shown that the prevalence of cognitive impairment is higher in MDD patients hospitalized during the acute phase.4 Specifically, a study conducted in 2024 found that the prevalence of cognitive impairment among MDD patients hospitalized during the acute phase was as high as 63.49%.5 Longitudinal studies have also consistently established a connection between MDD and MCI, showing that individuals with a history of depression are more likely to develop cognitive impairments, including MCI and even dementia, as they age.6, 7 In some cases, cognitive symptoms resembling MCI may manifest as part of depressive episodes.8, 9 Several studies indicate that neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and synaptic dysfunction may serve as shared pathological mechanisms between the 2 disorders.10 For example, chronic inflammation has been implicated in both depression and neurodegeneration, with cytokine dysregulation playing a key role in disease progression.11 Additionally, impairments in neurotransmitter signaling and neuronal plasticity have been observed in both MDD and MCI,12 further suggesting a common underlying biological basis. Despite evidence supporting this connection, the biological and neurological mechanisms underlying the link between MDD and MCI remain poorly understood. Further investigations into their interactions on a genetic and molecular basis are urgently needed.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and biological pathways underlying the comorbidity between MDD and MCI. To achieve this, we applied integrative bioinformatic methods,13 selecting the shared DEGs from transcriptomic datasets and subjecting them to enrichment analysis and protein–protein interaction (PPI) network construction to investigate the mechanisms and biomarkers involved in their interactions and mutual influence. This approach was intended to uncover molecular biomarkers that may provide insights into molecular overlaps, support early diagnosis, and serve as novel targets for mechanism-based therapeutic strategies and clinical interventions in patients with concurrent mood and cognitive symptoms.

Materials and methods

Microarray data sources

Microarray gene expression data were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Two transcriptomic datasets, GSE58430 and GSE140831, were selected. GSE58430 contains gene expression data from 12 patient samples (6 MDD and 6 healthy controls), while GSE140831 includes 664 samples (134 MCI and 530 healthy controls).

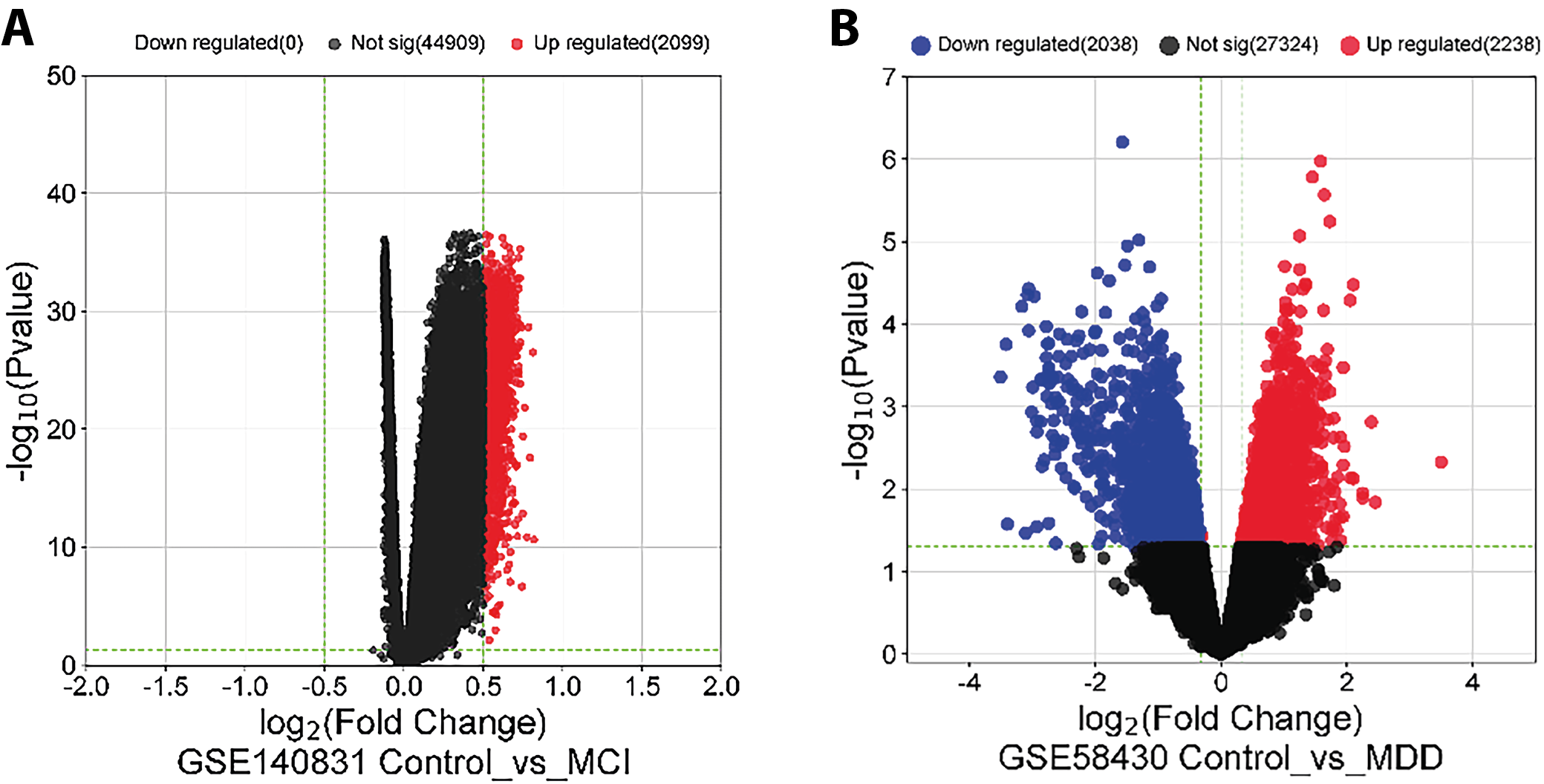

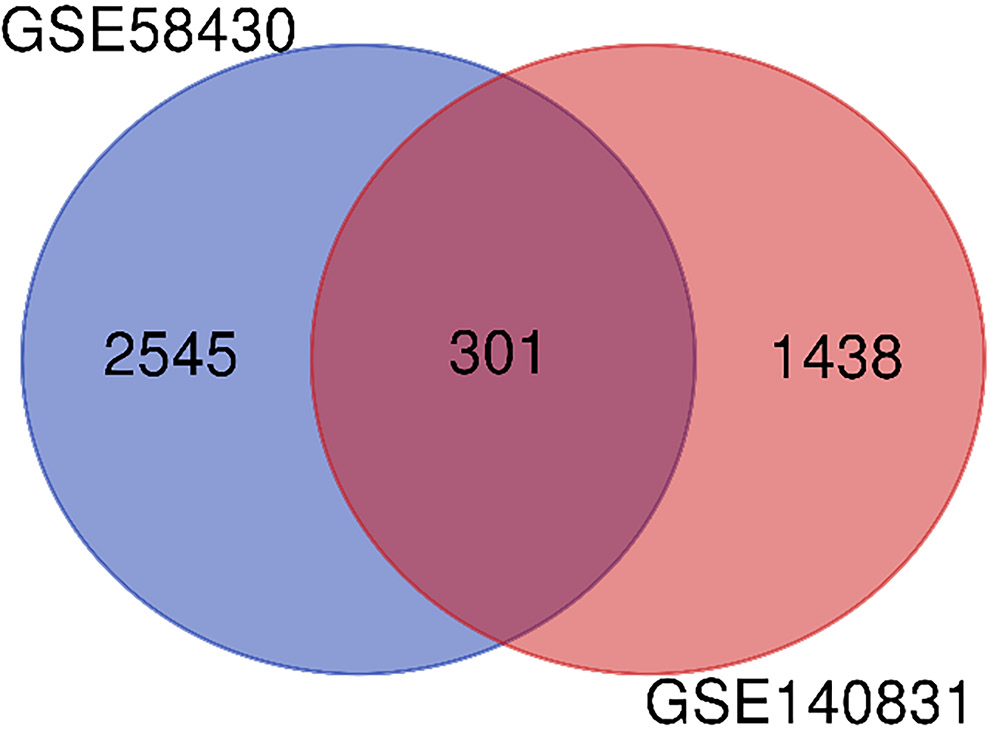

DEG analysis

Differential gene expression analysis was performed using GEO2R, an interactive web tool provided by the NCBI GEO that applies the limma (Linear Models for Microarray Data) package.14 For GSE58430, genes were considered differentially expressed if p < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 0.5. For GSE140831, the same threshold was applied (p < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 0.5). Probe annotations were verified using the respective platform annotation files. Differentially expressed genes identified in each dataset were then compared to determine the shared genes between MDD and MCI.

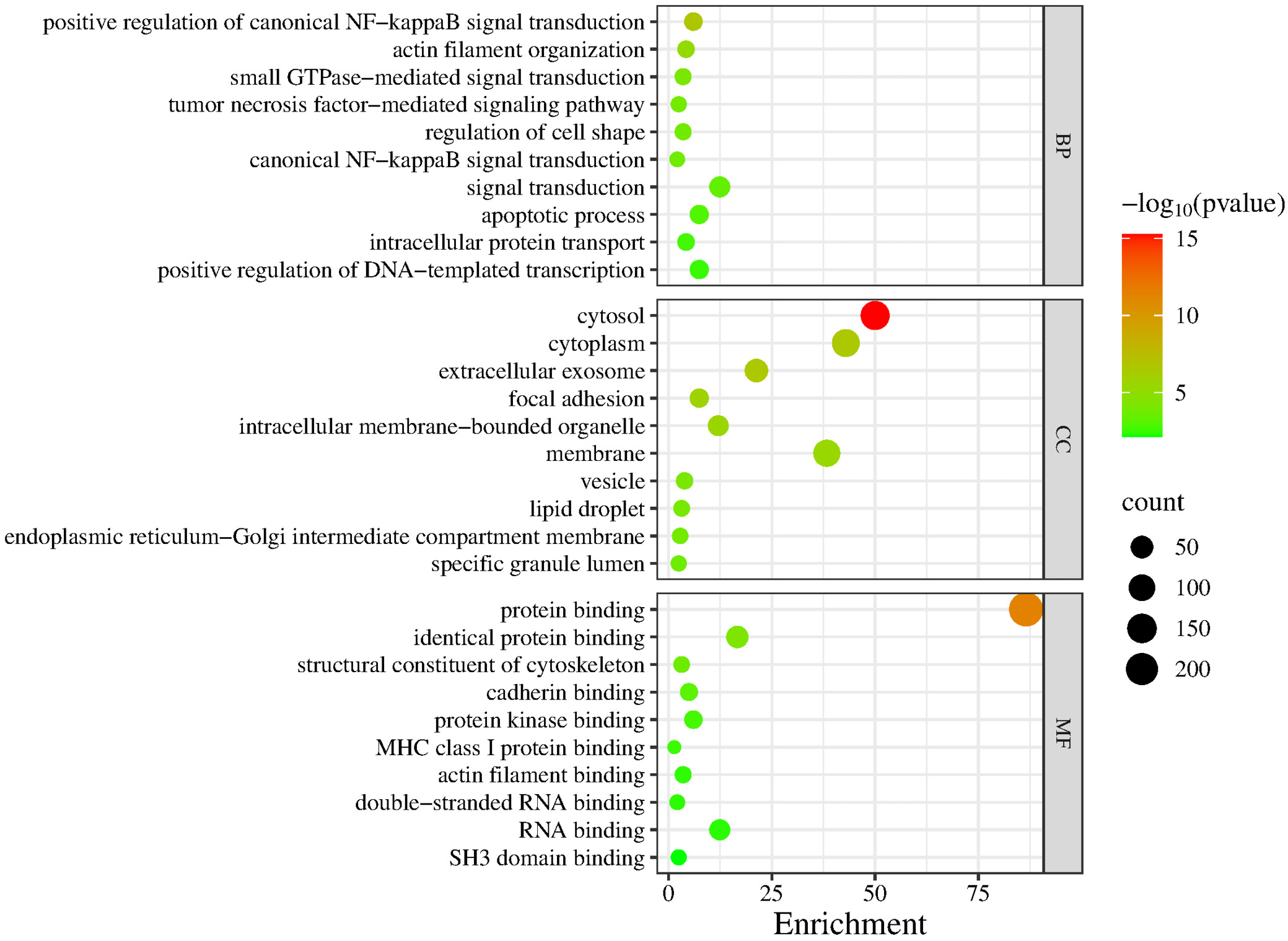

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment

Once the DEGs were identified, functional enrichment analysis was performed using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. Gene Ontology analysis classifies genes into functional categories based on their molecular functions, biological processes and cellular components, while KEGG analysis maps genes to specific signaling pathways and biological processes. Both analyses used the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; https://david.ncifcrf.gov/), which performs functional annotation clustering (FAC) to identify overrepresented or enriched biological processes, pathways, functional categories, and diseases/phenotypic annotations associated with the DEGs. Adjusted p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Protein–protein interaction analysis and core genes identification

Protein–protein interaction analysis was used to investigate interactions between proteins in the cell. Core genes were identified according to their importance in cellular functions. The PPI network was constructed using the STRING database (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins; https://string-db.org/) and analyzed with Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/). Differentially expressed genes with a high degree of connectivity to other genes were selected as core or hub genes.

Results

Identification of DEGs

A total of 3,122 genes were identified as depression-related DEGs in the GSE58430 dataset, of which 1,537 were downregulated and 1,585 were upregulated, as shown in the volcano plot (Figure 1A). In the GSE140831 dataset, 1,739 MCI-related DEGs were identified, all of which were upregulated (Figure 1B). The 301 genes shared between MDD- and MCI-related DEGs are shown in the Venn diagram (Figure 2).

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results

A total of 301 DEGs were submitted to GO analysis on the DAVID online platform, using p < 0.05 as the significance threshold. The results were visualized accordingly.

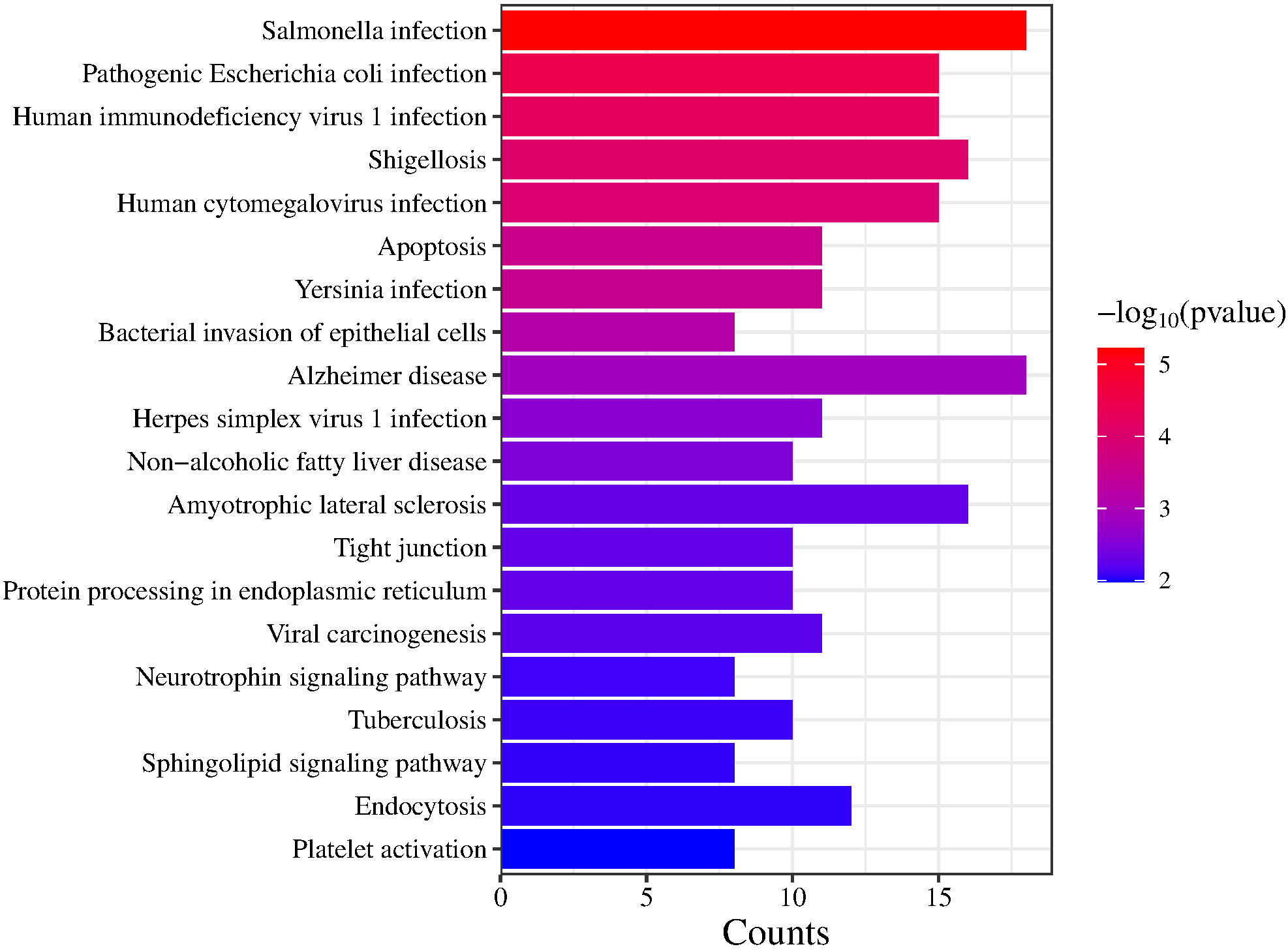

The GO terms were categorized into 3 domains: biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF) and cellular components (CC). In the BP domain, significantly enriched GO terms among DEGs shared between MDD and MCI included positive regulation of canonical NF-κB signaling, actin filament organization, small GTPase-mediated signal transduction, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated signaling pathway, and regulation of cell shape. In the CC domain, significantly enriched GO terms included cytosol, cytoplasm and extracellular exosome. In the MF domain, protein binding, identical protein binding, and structural constituent of the cytoskeleton were enriched. Figure 3 shows a comprehensive set of significantly enriched GO terms in bubble plots. The KEGG enrichment analysis identified several pathways that may play important roles in infection and apoptosis. Figure 4 shows these pathways, including Salmonella infection, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) infection, shigellosis, human cytomegalovirus infection, and apoptosis.

PPI analysis and core genes

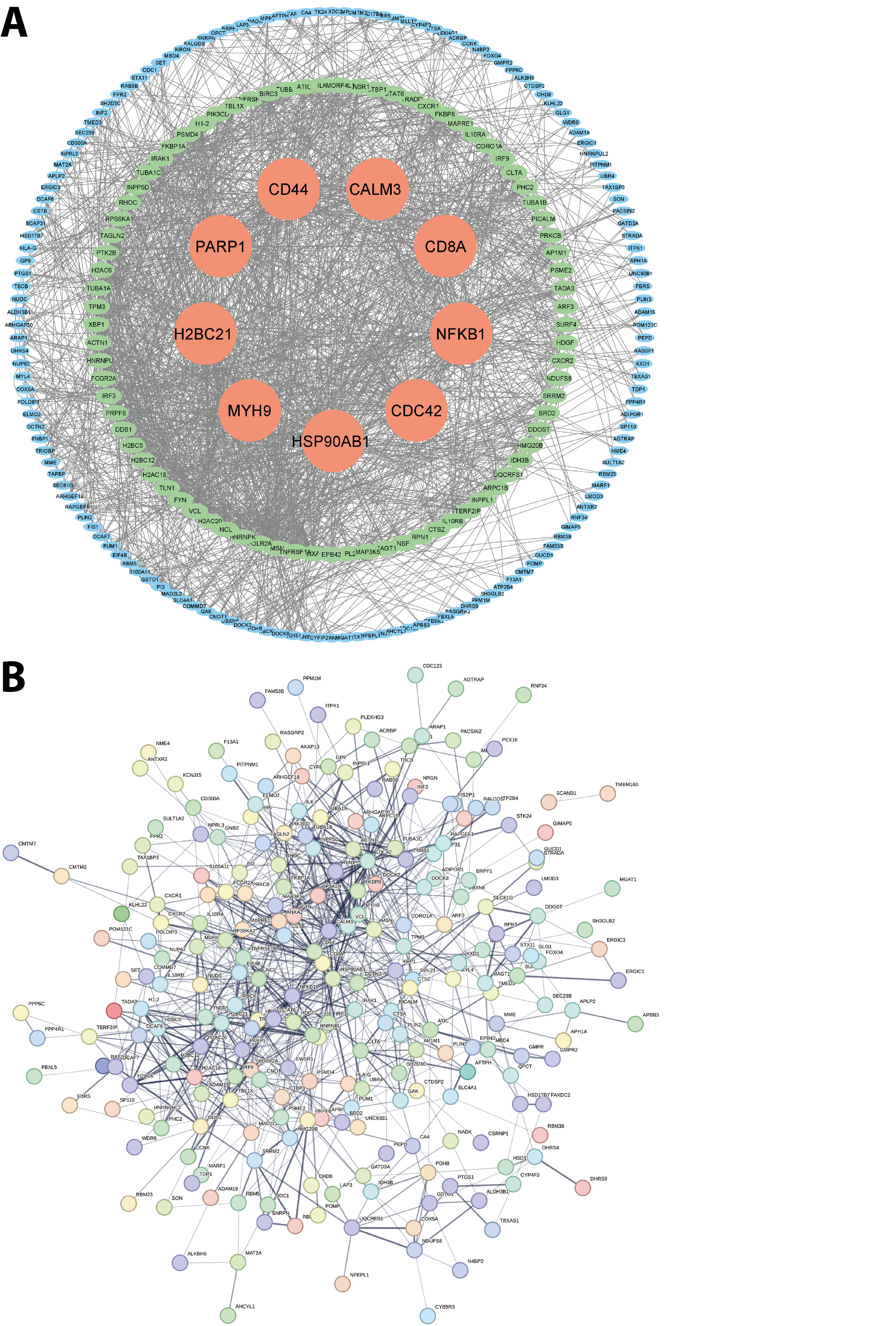

To further explore the interactions among DEGs shared between MDD and MCI, we performed a PPI network analysis, constructed with the STRING database (Figure 5A) and visualized in Cytoscape (Figure 5B). The network revealed 127 nodes with a degree greater than 10. Among the nine core genes identified as having the highest degree in the PPI network – HSP90AB1, CDC42, NFKB1, CD8A, CALM3, PARP1, CD44, H2BC21, and MYH9 – several are notable for their well-established roles in neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative conditions. Their centrality in the network and functional relevance suggest they may serve as candidate targets for early intervention or therapeutic development in the comorbidity of MDD and MCI.

Discussion

In this study, we identified 301 DEGs shared between MDD and MCI, many of which are implicated in key biological processes, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, synaptic dysfunction, and apoptotic signaling. Among these, HSP90AB1, CDC42, NFKB1, CD8A, CALM3, PARP1, CD44, H2BC21, and MYH9 were central within the PPI network. The functions of these genes and their associated pathways support the hypothesis that MDD and MCI share molecular mechanisms contributing to their comorbidity.

Identified biomarkers in regulating MDD and MCI

In our study, 9 hub genes mediating MDD and MCI were identified. Among them, the functions of HSP90AB1, CD8A, CD44, NFKB1, and CDC42 in linking MDD and MCI are supported by existing evidence from literature retrieval. HSP90AB1 may serve as a potential biomarker in the pathophysiology of depression and could influence the comorbidity of MDD and MCI. As a molecular chaperone, HSP90AB1 has also been identified as a major hub in the posterior cingulate cortex, an area significantly related to MDD.15 It has also been implicated in regulating posterior cingulate cortex microRNA dysregulation, which differentiates cognitive resilience, MCI, and Alzheimer’s disease.16 In our study, NFKB1 was identified as a central marker in the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) signaling pathway. The involvement of the NF-κB signaling pathway is critical, as it acts as a key regulator of neuroinflammatory responses. This pathway is known to be hyperactive in both MDD and neurodegenerative diseases such as MCI.17 Chronic neuroinflammation markers, including CD44 and CD8A, may be involved in responses to axon terminal degeneration and neuronal reorganization. In MDD, CD44 expression is dysregulated and is associated with immune cell infiltration. CD8A, a marker of CD8+ T cells, is more abundant in MDD samples. Together, changes in CD44 and CD8A may reflect altered immune responses in MDD.18 Neuroinflammation triggered by CD44 and CD8A contributes to MCI by promoting amyloid beta (Aβ) plaque deposition and tau pathology, which are key features of MCI progression.19 This indicates a potential link between MDD and MCI mediated by neuroinflammation. These targets may be considered candidate genes for the comorbidity of MDD and MCI. CDC42 is a key regulator of neuronal cytoskeletal dynamics and synaptic plasticity, which are critical for cognitive function and emotional regulation. The centrality and functional relevance of CDC42 in the network suggest that it may serve as a candidate target for early intervention or therapeutic development in MDD–MCI comorbidity.20

Identified pathways and mechanisms in regulating comorbidity of MDD and MCI

Among the enriched signaling pathways, positive regulation of canonical NF-κB signaling, small GTPase-mediated signal transduction, TNF-mediated signaling, apoptosis, and regulation of cell shape have been supported by existing evidence as relevant to the comorbidity of MDD and MCI. These pathways may therefore be highlighted as particularly important in modulating this comorbidity. The identified signaling pathways indicated that NF-κB signaling acts as a crucial inflammatory mediator in the comorbidity of MDD and MCI. Chronic stress and cellular damage activate NF-κB, driving pro-inflammatory cytokine production. This neuroinflammation can impair neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity in limbic and cognitive brain regions, thereby promoting neuronal dysfunction and contributing to both depressive symptoms (mood circuits) and cognitive decline (hippocampus, cortex).21 Overactivation of the TNF-mediated signaling pathway, a key pro-inflammatory pathway, drives the release of cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6, leading to sustained neuroinflammation.22, 23 Chronic inflammation exacerbates mood disturbances in MDD and contributes to synaptic degeneration and cognitive decline, hallmarks of MCI.24 The identification of the TNF-mediated signaling pathway in our study reinforces the hypothesis that inflammatory dysregulation is a shared driver of pathology in both disorders. Small GTPase-mediated signal transduction is also implicated in both MDD and MCI. These signaling pathways regulate essential cellular processes, and their dysregulation may contribute to neuroinflammation and synaptic dysfunction, common to both disorders. For instance, RhoA can activate NADPH oxidase (NOX) to generate superoxide ions, contributing to oxidative stress and neuronal cell death in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.25 Oxidative stress and inflammation can also affect cognitive function and mood regulation, potentially influencing the comorbidity of MDD and MCI.25, 26 The enriched apoptosis pathway may also contribute to the comorbidity of MDD and MCI through the neuroinflammatory processes discussed above. Neuroinflammation may disrupt normal synaptic activity and neuronal structure via the regulation of cell shape pathway identified in our KEGG analysis, which is implicated in both MDD and MCI.27

Possible mechanisms of neuroinflammation, synaptic signaling and apoptotic mechanisms in linking the progression of MDD and MCI

Our findings on biomarkers and pathways jointly indicate that neuroinflammation, synaptic signaling and apoptotic mechanisms play fundamental roles in linking the progression of MDD and MCI. Beyond these mechanisms, neuroinflammation in this comorbidity can activate CD44 and CD8A molecules and trigger pathways such as NF-κB signaling, TNF-mediated signaling and apoptosis. Furthermore, neuroinflammation may compromise the blood–brain barrier (BBB), allowing peripheral immune cells and inflammatory factors to infiltrate the central nervous system. Disruption of the BBB has been implicated in both depression-related cognitive dysfunction and early-stage MCI.28 PARP1 and NCL, which play roles in DNA repair and inflammatory responses, may contribute to BBB dysfunction.29, 30 Dysregulation of these genes could lead to increased neuroinflammation and neuronal damage, further linking MDD and MCI at a molecular level. Our findings indicate that synaptic signaling, mediated by CDC42, a marker identified in our study, is closely associated with synaptic plasticity and neuronal network formation. Research shows that synaptic plasticity and neurotransmission are significantly altered in MDD patients, contributing to mood and cognitive dysfunction. These alterations may also be involved in the pathophysiological changes underlying MCI. The interplay between synaptic signaling and other molecular pathways may provide insights into the comorbidity of MDD and MCI. Apoptotic mechanisms have also been proposed as contributing to this link. In MDD, inflammation-induced apoptosis in the hippocampus can lead to neuronal loss and cognitive dysfunction. Similarly, apoptotic processes may exacerbate neuronal damage in MCI, potentially involving the release of pro-apoptotic factors such as p53, which is elevated in MCI. These mechanisms may drive further cognitive decline and emotional dysregulation underlying the comorbidity of MDD and MCI.10, 31

Taken together, these processes are interrelated. Neuroinflammation mediated by CD44, CD8A, and NF-κB activation can induce oxidative stress and apoptosis, leading to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss. Additionally, cytoskeletal regulators such as CDC42 integrate inflammatory signals and modulate synaptic remodeling and plasticity. PARP1 acts as a molecular bridge between DNA damage responses and inflammatory cascades. This interplay creates a self-reinforcing cycle in which neuroinflammation, synaptic impairment and apoptosis converge on a common set of molecular effectors. These shared pathogenic pathways likely underlie the consistent differential expression of the hub genes identified in both MDD and MCI.

Possible mechanisms of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in linking the progression of MDD and MCI

Oxidative stress represents another major contributor to both depression and cognitive impairment. It leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, neuronal apoptosis and impaired neurotransmission.32 Among the DEGs identified, PARP1 is a key gene mediating oxidative DNA damage repair in MDD and MCI. However, excessive activation of PARP1 can deplete cellular energy, promoting neuronal death through a process known as parthanatos.33 This mechanism is relevant to both MDD and MCI, where mitochondrial dysfunction related to oxidative stress has been widely reported.34

The interaction between oxidative stress and inflammation further exacerbates disease progression. Given its dual role in inflammation and DNA damage repair, PARP1 serves as a mechanistic bridge between chronic inflammation and neuronal dysfunction in MDD and MCI. PARP1 inhibitors, such as olaparib, are currently in clinical trials for neurodegenerative diseases, suggesting their potential for therapeutic repurposing in MDD-MCI comorbidity.35 The NF-κB pathway, previously described, is also activated by oxidative stress and induces chronic inflammatory signaling.36 This vicious cycle of inflammation and oxidative stress is a well-documented feature of both MDD and neurodegenerative disorders.37, 38

Notably, this mechanistic cascade also involves transcriptional upregulation of NFKB1, as oxidative stress and PARP1 activation can induce NF-κB autoregulatory feedback loops. Increased expression of NFKB1 and persistent NF-κB activation perpetuate chronic inflammation and neuronal injury. This reciprocal relationship between PARP1 and NFKB1 likely underlies their consistent identification as shared hub genes in our analysis, highlighting a convergent pathway linking oxidative damage, inflammatory signaling and neurodegeneration in both MDD and MCI.

Functions of neural connectivity signaling in linking MDD and MCI

Currently, cognitive dysfunction in both MDD and MCI is considered to be linked to disrupted synaptic plasticity, which can subsequently impair neuronal connectivity. Several key genes identified in our study, including CDC42 and CALM3, are known regulators of neuronal cytoskeletal dynamics and calcium signaling.

CDC42 plays a critical role in dendritic spine formation and axonal remodeling, both of which are essential for maintaining functional neural circuits. Impaired CDC42 function leads to defective neuronal connectivity and synaptic signaling. This may result in disrupted or misconnected neural circuits, reducing communication efficiency across brain regions. Experimental models show that CDC42 knockout causes deficits in long-term potentiation (LTP) and remote memory recall,39 functions impaired in both MDD and MCI. Modulating CDC42 activity presents a promising approach for restoring cognitive resilience.40, 41

CALM3 is a key modulator of calcium-dependent neurotransmitter release and neural connectivity. Dysfunction in CALM3-related pathways could impair LTP and long-term depression (LTD), which are essential for learning and memory.42 CALM3 also interacts with multiple kinases and phosphatases that regulate neuronal excitability and neural connectivity, suggesting its dysfunction could underlie both affective and cognitive symptoms. Clinically, altered calmodulin levels have been detected in postmortem brain tissues and peripheral samples of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders, indicating a potential role for CALM3 as a biomarker of dysfunction in synaptic plasticity and neural connectivity.43 Additionally, modulators of calcium signaling pathways are being explored as therapeutic agents in both depression and dementia,44, 45 highlighting the translational relevance of CALM3 in comorbid MDD-MCI treatment strategies. Thus, the convergence of CDC42 and CALM3 dysregulation likely reflects their shared roles as critical mediators of synaptic remodeling in response to cellular stress. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, previously described, can disrupt calcium homeostasis and cytoskeletal dynamics, leading to compensatory or maladaptive changes in the expression of these genes. This mechanistic interplay provides a plausible explanation for the emergence of CDC42 and CALM3 as shared hub genes in our analysis, as their dysregulation integrates inflammatory signaling, impaired neurotransmission and deficits in cognitive processing characteristic of both MDD and MCI.

Pathway enrichment highlights overlapping biological mechanisms

In addition to gene-level insights, our pathway enrichment analysis identified several pathways that further support the shared pathophysiology of MDD and MCI. The shigellosis pathway enriched in our KEGG results, associated with immune activation and inflammatory responses, may contribute to neuroinflammation and BBB integrity disruption.46 The platelet activation pathway, enriched in our KEGG analysis, and platelet aggregation, enriched in our GO-BP analysis, are linked to vascular dysfunction, which has been implicated in both MDD and neurodegenerative diseases.28 The neurotrophin signaling pathway, enriched in our KEGG analysis and regulating neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity, is often dysregulated in both mood and cognitive disorders.47 These pathways highlight the intricate interplay between immune dysregulation, vascular integrity and neuroplasticity, all critical to the development of both conditions. While certain KEGG pathways, such as shigellosis and Salmonella infection, were enriched, this likely reflects involvement of shared immune-related genes rather than direct pathogen-specific processes. This observation underscores the central role of immune activation in MDD and MCI.

Moreover, many of the hub genes identified in our PPI analysis, such as NFKB1, CD44 and CDC42, are directly involved in mediating these pathways, underscoring their central role as integrative nodes linking immune activation, vascular dysfunction and impaired neuroplasticity. The convergence of these processes likely drives the shared transcriptional signatures observed in both MDD and MCI datasets. This reinforces the notion that comorbid mood and cognitive symptoms arise from interconnected pathophysiological mechanisms rather than isolated processes.

Limitations

While this study reveals key genes and pathways linking MDD and MCI, further validation in patient-derived tissue and longitudinal cohorts is needed to confirm causality and directionality. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics could deepen our understanding of cell-type-specific expression changes, particularly in vulnerable brain regions. Moreover, integrating proteomics and metabolomics may further uncover post-transcriptional and metabolic alterations that gene expression data alone cannot resolve. Finally, although bioinformatics analyses provide valuable hypotheses, we did not experimentally validate gene expression, such as using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) or western blot verification of the identified hub genes. This is an important limitation, as experimental confirmation is needed to corroborate the in silico differential expression patterns. Functional studies in animal models and human-derived organoids will be essential to elucidate the mechanistic roles of the identified DEGs and to test targeted therapeutic interventions. We plan to address this in future work through qPCR and protein-level validation in patient-derived samples or relevant preclinical models.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified 301 DEGs shared between MDD and MCI, revealing significant overlap in the molecular mechanisms underlying both conditions. Integrative bioinformatics analyses revealed that these DEGs are enriched in pathways related to neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, synaptic plasticity, and epigenetic regulation – hallmarks of both mood and cognitive disorders. Notably, several hub genes, including HSP90AB1, CD8A, CD44, NFKB1, CALM3, and CDC42, demonstrated strong functional relevance and translational potential.

These findings suggest that the identified genes may serve as novel biomarkers for the early detection of MDD-MCI comorbidity and as mechanism-based therapeutic targets. Although further experimental validation is needed, our study provides a foundation for developing diagnostic tools and personalized treatment strategies for individuals at risk for concurrent mood and cognitive decline.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study were already openly available when the research project commenced and can be accessed in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/):

GSE58430: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE58430

GSE140831: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE140831

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.