Abstract

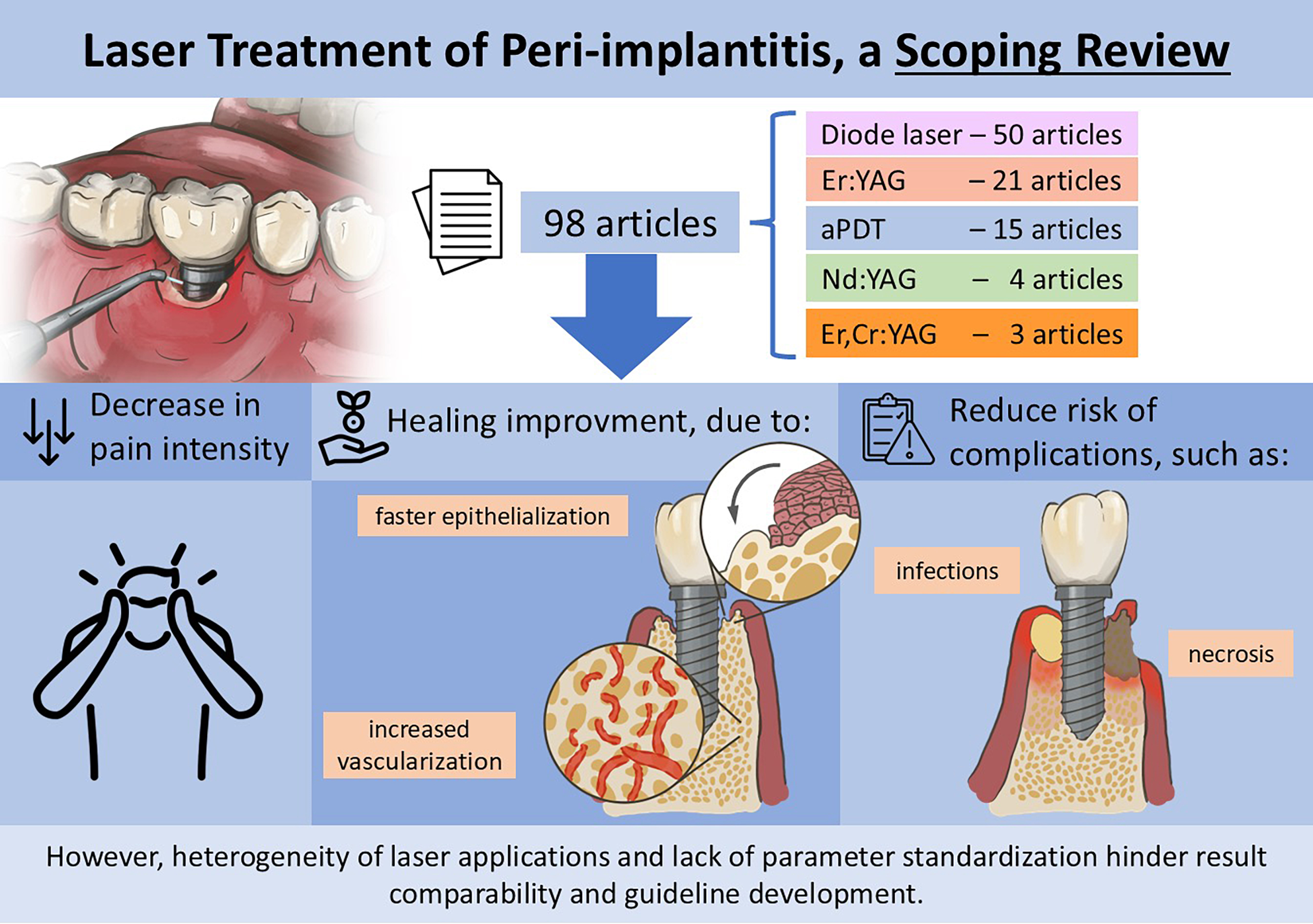

Peri-implantitis poses a persistent challenge in implant dentistry, driving interest in laser therapy as a potential treatment option. Despite encouraging outcomes, clinical applications of laser therapy differ significantly in terms of wavelength, power setting and session frequency, hindering the development of standardized protocols. This scoping review aimed to map and synthesize current clinical evidence on the efficacy of laser therapy in peri-implantitis management, identify knowledge gaps and provide a foundation for future clinical recommendations. Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines, a comprehensive search was conducted across 5 databases (Scopus, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science) between May and July 2024, covering studies published from 2000 to 2024, with no language restrictions. Two independent reviewers extracted data with high inter-rater agreement (κ = 0.97). A total of 98 clinical studies were included: 56 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 38 cohort studies and 4 retrospective studies. Diode lasers were the most frequently studied (n = 50), followed by Er:YAG, aPDT, Nd:YAG, and Er,Cr:YSGG lasers. Exposure times ranged from 10 s to 700 s, most commonly around 60 s. Key clinical outcomes included probing depth (PD) reduction, bleeding on probing (BoP) and plaque index (PI), with additional outcomes related to bone loss, clinical attachment level (CAL), gingival recession (REC), cytokine levels, microbial analysis, suppuration, and gingival index (GI). Overall, laser therapy was associated with reduced inflammation, accelerated epithelialization, improved bone parameters, fewer complications, and better patient-reported outcomes. While laser therapy shows considerable promise in the treatment of peri-implantitis, further robust and standardized clinical research is essential to confirm its efficacy, optimize treatment parameters and inform evidence-based clinical guidelines.

Key words: dental implants, phototherapy, peri-implantitis, laser therapy low-level, anti-infective agents

Introduction

Peri-implantitis is an inflammatory condition affecting the tissues around dental implants, leading to the progressive destruction of supporting bone and potentially resulting in implant failure.1 Due to increasing implant longevity and rising global life expectancy, peri-implantitis prevalence at the patient level is estimated to range from 8.9% to 45%,2 influenced by diagnostic criteria and evaluated population characteristics.3 Despite recent indications of a slight decline in its average prevalence, peri-implantitis continues to present significant challenges in implant dentistry, adversely affecting implant stability and rehabilitative outcomes.4

The etiology of peri-implantitis is multifactorial, with bacterial biofilm formation around implants identified as the primary inflammatory trigger.5, 6 Contributing risk factors include poor oral hygiene, smoking, systemic diseases like diabetes, and specific anatomical and prosthetic features complicating peri-implant health maintenance.7 Recent advancements in understanding the molecular mechanisms of peri-implantitis, such as immune cell activation pathways and inflammatory cytokine profiles, have provided new perspectives into the disease’s complexity and progression.8

The pathogenesis of peri-implantitis is recognized as multifactorial, shaped by the interplay between bacterial biofilm, host immune responses and implant-related factors.5 Beyond biofilm accumulation, variations in the host’s immune regulation – such as overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators, and macrophage polarization toward a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype – intensify peri-implant tissue destruction.6 The physical and chemical characteristics of implant surfaces – including micro- and nanotopography, as well as corrosion byproducts such as titanium particles – further influence immune cell recruitment and cytokine expression, thereby perpetuating inflammation and bone resorption.7 Genetic predispositions, systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, local factors including limited keratinized mucosa, and behavioral factors such as smoking synergistically increase this risk.6 According to the Biofilm-Mediated Inflammation and Bone Dysregulation (BIND) model proposed by Ng et al., peri-implantitis arises when the delicate balance among biofilm control, immune response and bone remodeling fails, pushing the system beyond a tipping point that results in a clinically evident disease characterized by progressive bone loss and soft tissue inflammation.8

Traditionally, the treatment of peri-implantitis has predominantly relied on mechanical and chemical interventions, including implant surface scaling, smoothing and antimicrobial therapies.9 However, these conventional approaches have limitations in effectively decontaminating implant surface and promoting bone regeneration.10 In this context, laser therapy has emerged as a promising alternative owing to its bactericidal properties and potential to promote tissue regeneration.11, 12, 13 Additionally, lasers offer a minimally invasive approach, crucial for minimizing further bone loss.14 Various lasers demonstrate distinct advantages: the Er:YAG laser effectively removes biofilm, significantly reducing probing depth (PD) and gingival recession (REC) compared to conventional mechanical methods15, 16; the Nd:YAG laser is beneficial for deeper tissue penetration,17 preserves implant surface morphology,18 but both lasers achieving significant implant surface decontamination.19 Diode lasers and antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) also show considerable efficacy in peri-implantitis management, further emphasizing the versatility and potential of laser-based treatments.20

Despite these promising outcomes, standardized clinical guidelines for laser therapy in peri-implantitis treatment remain lacking due to wide variability across studies regarding parameters, such as laser wavelength, power settings and treatment session frequency.

Objectives

The objective of this scoping review was to map and critically evaluate the current scientific literature on the use of laser therapy in the management of peri-implantitis. This review aimed to synthesize the available evidence regarding clinical efficacy, identify existing knowledge gaps, and provide a foundation for developing future clinical recommendations.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

This review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines21 for scoping reviews. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across 5 major databases: Scopus, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science. The search aimed to identify relevant studies investigating the efficacy of laser therapy in the treatment of peri-implantitis. Following the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodological guidance for scoping reviews,22 we structured the research question using the Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework. This decision was based on the primary aim of this scoping review: to map, describe and synthesize the existing clinical evidence regarding the use of laser therapy for peri-implantitis. Accordingly, our PCC question was formulated as follows: Population (P): Patients diagnosed with peri-implantitis; Concept (C): Use of laser therapy as a treatment modality; Context (C): Clinical studies reporting clinical and radiographic outcomes, regardless of design or setting

In narrative form, the research question guiding this scoping review was: “Among patients with peri-implantitis (Population), what has been reported in the clinical literature regarding the use of laser therapy (Concept), across different clinical settings and study designs (Context)?”

The search was performed between May 2024 and July 2024 covering studies published over the past 15 years (2000–2024), but only studies published in English were included. The following keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were used:

MeSH Terms (peri-implantitis)

“Peri-implantitis’’ OR “Peri-implantitides’’ OR “Periimplantitis’’ OR “Periimplantitides’’

MeSH Terms (laser therapy)

“Laser Therapies’’ OR “Therapies, Laser’’ OR “Therapy, Laser’’ OR “Vaporization, Laser’’ OR “Laser Vaporization’’ OR “Laser Ablation’’ OR “Ablation, Laser’’ OR “Laser Tissue Ablation’’ OR “Ablation, Laser Tissue’’ OR “Tissue Ablation, Laser’’ OR “Pulsed Laser Tissue Ablation’’ OR “Laser Photoablation of Tissue’’ OR “Nonablative Laser Treatment’’ OR “Laser Treatment, Nonablative’’ OR “Laser Treatments, Nonablative’’ OR “Nonablative Laser Treatments’’ OR “Laser Scalpel’’ OR “Laser Scalpels’’ OR “Scalpel, Laser’’ OR “Scalpels, Laser’’ OR “Laser Knives’’ OR “Knive, Laser’’ OR “Knives, Laser’’ OR “Laser Knive’’ OR “Laser Knife’’ OR “Knife, Laser’’ OR “Knifes, Laser’’ OR “Laser Knifes’’ OR “Laser Surgery’’ OR “Laser Surgeries’’ OR “Surgeries, Laser’’ OR “Surgery, Laser’’.

MeSH Terms (CO2 laser)

“Carbon Dioxide Lasers’’ OR “Carbon Dioxide Laser’’ OR “Dioxide Laser, Carbon’’ OR “Dioxide Lasers, Carbon’’ OR “Laser, Carbon Dioxide’’ OR “Lasers, CO2’’ OR “CO2 Lasers’’ “CO2 Laser’’ OR “Laser, CO2’’ OR “Lasers, Carbon Dioxide’’.

MeSH Terms (photodymanic therapy)

“Photochemoterapy’’ OR “Photochemotherapies’’ OR “Photodynamic Therapy’’ OR “Therapy, Photodynamic’’ OR “Photodynamic Therapies’’ OR “Therapies, Photodynamic’’ OR “Red Light Photodynamic Therapy’’ OR “Red Light PDT’’ OR “Light PDT, Red’’ OR “PDT, Red Light’’ OR “Blue Light Photodynamic Therapy’’.

MeSH Terms (diode laser)

“Diode Lasers’’ OR “Diode Laser’’ OR “Laser, Diode’’ OR “Lasers, Diode’’. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were applied to combine keywords, and reference lists of relevant articles were manually searched to ensure a thorough inclusion of studies. Any duplicates identified across databases were removed using Rayyan reference manager software (https://www.rayyan.ai).

Study selection

Studies included in the systematic review met the following eligibility criteria:

Inclusion criteria: 1) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective studies, case-control studies; 2) Studies that evaluated the clinical outcomes of laser therapy in the treatment of peri-implantitis; 3) Articles that reported quantitative outcomes such as changes in: bleeding on probing (BoP), PD, clinical attachment level (CAL), bone loss, bone regeneration, and cytokines release; 4) Human studies that involved the use of lasers (e.g., Er:YAG, Nd:YAG, CO2, Er,Cr:YSGG, diode lasers) either as monotherapy or as adjunct therapy to mechanical debridement.

Exclusion criteria: 1) Animal studies, in vitro studies, reviews, meta-analyses, expert opinions, case series, and case reports; 2) Studies not focusing on peri-implantitis or those where laser therapy was used for other peri-implant diseases; 3) Studies where peri-implantitis treatment was combined with other modalities that did not allow for isolated assessment of laser therapy’s efficacy.

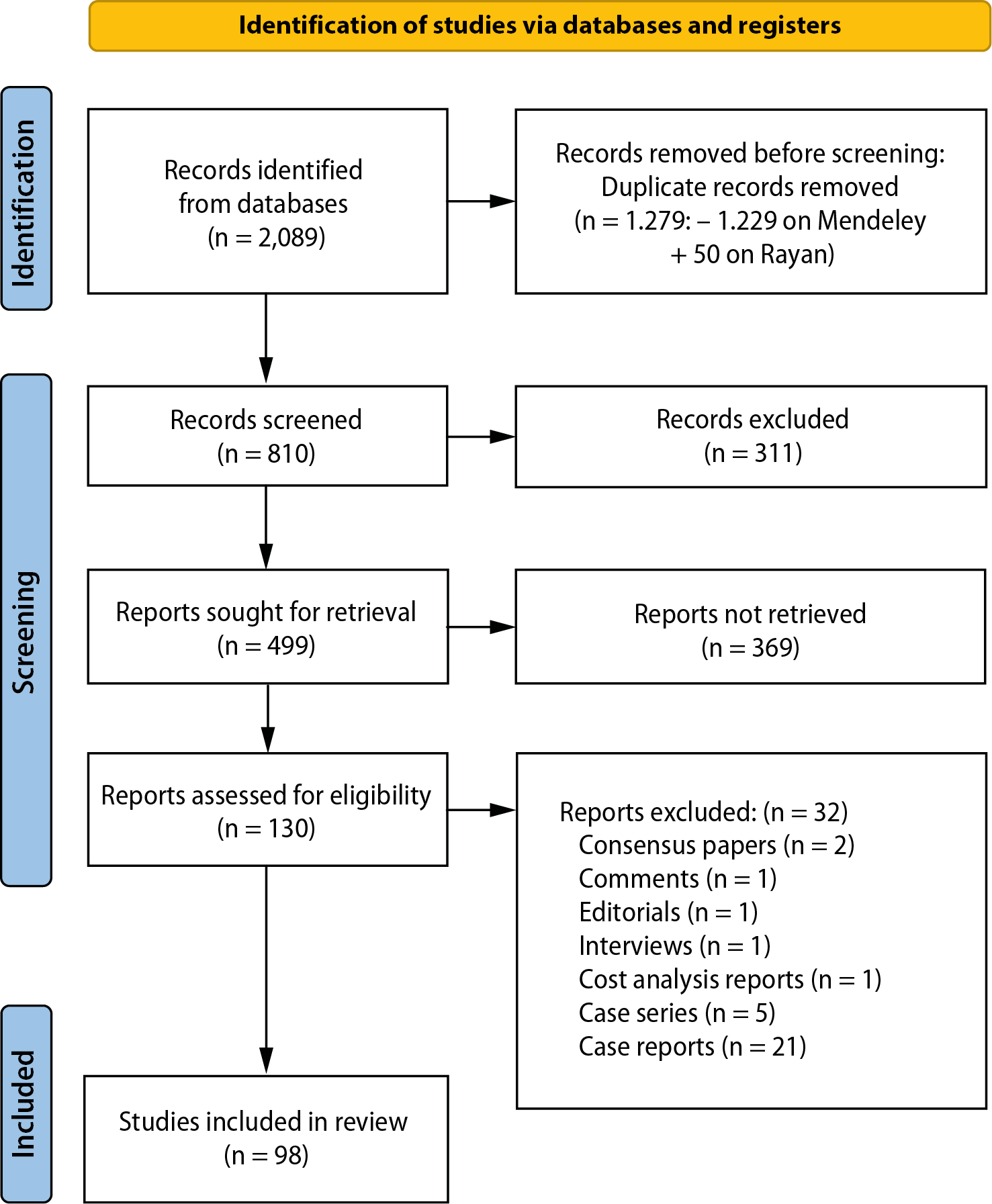

The study selection process is presented in the flow diagram (Figure 1). Initially, a comprehensive search across multiple databases, including Scopus (610), PubMed (475), Cochrane Library (212), Embase (446), and Web of Science (346), yielded a total of 2,089 records. Following the removal of duplicates – 1,229 through Mendeley and an additional 50 using Rayyan – a total of 810 unique records remained for further screening.

The titles and abstracts of these 810 records were reviewed, and 311 records were excluded due to irrelevance to the research topic. The remaining 499 records were selected for full-text retrieval to assess their eligibility for inclusion in the review. However, 369 of these reports could not be retrieved for various reasons. Some were abstracts (11), poster presentations (4), studies focused on laser applications to the implant surface (6), or non-English language studies (6). Additionally, other records included book chapters (7), books (2), protocol registers (40), systematic reviews (147), and in vitro, in vivo or ex vivo studies (146), all of which were not eligible for inclusion.

From the 130 full-text articles that were retrieved and thoroughly assessed for eligibility, 32 reports were excluded. These exclusions were based on the nature of the reports, which included consensus papers (2), comments (1), editorials (1), interviews (1), cost analysis reports (1), case series (5), and case reports (21), none of which met the criteria for this systematic review. Ultimately, 98 studies were included in the systematic review. These studies comprised 56 randomized clinical trials, 38 prospective cohort studies and 4 retrospective studies. They formed the basis of the data synthesis and subsequent evaluation. The flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by 2 reviewers using a standardized data extraction form. The following information was collected from each included study:

Study characteristics: authors, year of publication, country, study design, sample size, and duration of follow-up.

Patient characteristics: mean age, sex, number of implants affected, presence of comorbidity, and baseline severity of peri-implantitis.

Laser parameters: type of laser used, wavelength, mode of application (monotherapy or adjunct), and number of treatment sessions.

Outcome measures: changes in PD, CAL, bone regeneration, BoP, and any reported adverse effects.

If data were missing or unclear, the study authors were contacted via email once a week for up to 4 weeks to request clarification. Any disagreements between reviewers during the data extraction process were resolved by consensus.

The inter-rater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa, which yielded a value of κ = 0.97, indicating substantial agreement between the examiners (L.J.S. and F.V.J.). In cases of disagreement, a 3rd reviewer was consulted to resolve conflicts (F.F.).

Results

The results of this review include 98 studies, with 38 being prospective,23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 4 retrospective20, 61, 62, 63 and 56 RCTs.20, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118 The studies were published between 2000 and 2024, with the mean age of participants ranging from 24 to 68.5 years; however, 18 studies did not report participant age.19, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 34, 50, 52, 62, 63, 66, 80, 93, 96, 97, 102, 118

In terms of geographic distribution, 29 studies were from Saudi Arabia,31, 37, 38, 39, 40, 44, 46, 47, 48, 49, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 59, 81, 83, 86, 87, 90, 91, 92, 98, 99, 110,

114, 115, 117 15 from Italy,27, 32, 34, 43, 51, 19, 62, 63, 69, 71, 80, 88, 96, 103, 108 12 from Germany,23, 24, 26, 28, 30, 41, 64, 65, 68, 70, 74, 85 and 7 from the USA33, 61, 96, 97, 109, 111, 118; there were also contributions from 16 other countries. Most studies (66) did not report comorbidities, while 32 studies did,31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 54, 56,

57, 61, 69, 72, 81, 83, 86, 89, 91, 92, 94, 95, 100, 107, 108, 110, 114, 115 reporting conditions such as smoking, diabetes, chemotherapy, bisphosphonate use, immunocompromised states, obesity, depression, and hyperglycemia.

Regarding laser applications, 79 studies performed a single application, 6 performed 2 applications,34, 36, 75, 82, 93, 96 9 performed 3,35, 51, 61, 77, 90, 99, 102, 107, 114 and the highest number of applications was 8, seen in just 1 study.103 Some studies had groups with different numbers of applications. Most studies (89) did not report side effects, but dehiscence, edema, mucosal recession, and bone loss were noted in a few cases.

The follow-up period varied from 12 weeks to 9 years, with 71 studies19, 20, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 44, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 70, 71, 72, 74, 75, 76, 77, 84,

85, 87, 89, 90, 96, 97, 99, 101, 102, 103, 104, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 114, 115, 116, 118 evaluating outcomes over at least 6 months. In terms of laser types, the diode laser was the most frequently used (50 studies23, 24, 27, 28, 31, 32,

34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 9, 60, 62, 71, 73, 75, 76, 77, 79, 80, 82, 83, 86, 88, 91, 92, 94, 95,

98, 101, 104, 105, 106, 107, 110, 112, 114), followed by Er:YAG (21 studies30, 39, 42, 50,

52, 19, 64, 66, 67, 68, 70, 74, 84, 85, 97, 102, 107, 108, 109, 118), aPDT (15 studies25, 29, 33, 43,

58, 63, 69, 72, 79, 87, 89, 93, 99, 103, 113), Nd:YAG (4 studies50, 61, 96, 20), Er,Cr:YSGG (3 studies101, 107, 116), and others such as GaAlAs,

CO2 and infrared lasers.

Exposure times were not specified in 29 studies.30, 33, 36,

41, 42, 50, 52, 56, 61, 64, 66, 67, 68, 70, 72, 74, 77, 81, 84, 85, 96, 101, 102, 108, 109, 20, 111, 116, 117 Among those that did report exposure times, the shortest was 10 s per site (in 11 studies29, 31, 43, 45, 46, 49, 73, 75, 86, 87, 89), while the longest was 700 s.115 The most common exposure time was 60 s, used in 18 studies.26, 28, 32, 44, 47, 55, 57, 59, 73, 80,

89, 91, 93, 95, 105, 107, 112, 114

The studies reviewed indicate that dental implants were placed in the maxilla and mandible, focusing on the premolar and molar regions. A consistent pattern was observed, with most studies reporting the placement of 6 sites per implant. For instance, in various groups, a total of 9–29 implants were positioned in the maxilla and 29–58 implants in the mandible across different patient cohorts. The distribution of implants also revealed a higher prevalence in the molar region compared to premolar and anterior sites.

The primary equipment used across the studies includes a variety of laser systems and photodynamic therapy (PDT) devices. The most frequently wavelengths used in PDT were 660 nm and 2 different devices are the most frequently used (HELBO® TheraLite Laser and 3D Pocket Probe (Photodynamic Systems GmbH, Sendem, Germany), and Periowave™ (Ondine Biopharma, Vancouver, Canada)). Currently, different types of LED devices are also being used for PDT, with a wavelength of 630 nm (FotoSan® CMS Dental, Copenhagen, Denmark). In reference to erbium lasers, 2 different wavelengths are used (2,940 nm and 2,780 nm). There are different devices that use the 2,940 nm Er:YAG laser, among the most used are LightWalker, Fotona, Ljubljana, Slovenia; AdvErL EVO, Morita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan; and KEY3® and KEY3s KaVo, Biberach, Germany. With respect to the wavelength of 2,780 nm, the most frequently used device is the iPlus and MD (Biolase Technology, Inc., Foothill Ranch, USA). Different wavelengths are used in diode lasers, the most common being 980 nm, 810 nm (Wiser Doctor Smile Laser D5 Lambda Scientifica SPA and FOX laser from A.R.C. lasers, Nuremberg, Germany) and 940 nm (Biolase Technology, Inc.). Currently, some diode lasers incorporate different wavelengths such as 450 nm, 650 nm and/or 810 nm/980 nm in the same device (Pioon Technology Co., Ltd. Wuhan, China).

The analyzed articles utilize a variety of laser powers and frequencies in treatments, with powers ranging from 60 mW to 6 W. Most lasers operate at frequencies between 10 Hz and 50 Hz, while some reach up to 30 kHz. The wavelengths primarily vary between 630 nm and 2,940 nm, including the 10,600 nm CO2 laser, with various applications of lasers in both continuous and pulsed modes. Diode lasers with powers of 100 mW, 150 mW, 200 mW, and 300 mW are common, as well as Er:YAG lasers with powers ranging from 1.5 W to 4.5 W. Other lasers, such as Nd:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG, are also used with different energy and density configurations, varying from 12.7 J/cm2 to 350 J/cm2.

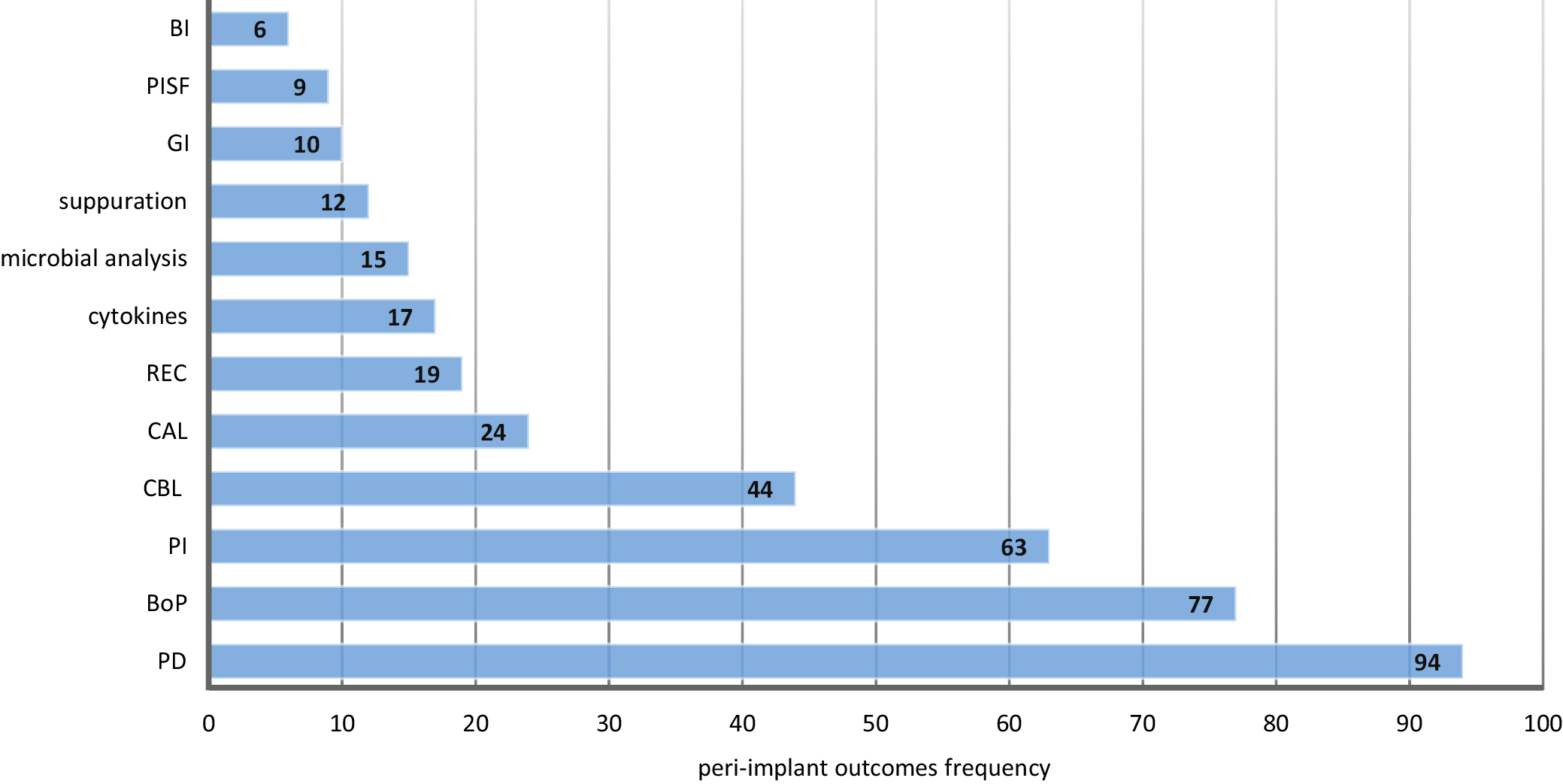

The frequency of the outcomes variables analyzed in the selected studies are presented in the Figure 2. The most frequently reported variables were PD, which appeared 94 times,19, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118 and BoP, mentioned 77 times.19, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 55, 56, 57, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 70, 71, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 97,

101, 102, 103, 104, 106, 108, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118 Plaque index (PI) was described 63 times,20, 26, 32, 34, 39, 40, 41, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 64, 65, 67, 68, 70, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 80, 81, 82, 83, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 91, 92, 93, 94,

96, 97, 99, 101, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 110, 112, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118 while crestal bone loss (CBL) appeared in 4419, 23, 24, 25, 26, 33, 39, 40, 42, 44, 45, 50, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 59, 60, 61, 62, 65, 66, 68, 72, 76, 85, 87,

90, 91, 92, 96, 98, 99, 100, 102, 104, 105, 110, 111, 114, 115, 116 studies, and CAL in 24 studies.20, 27, 28, 29, 52, 64, 65, 68, 70, 71, 73, 74, 75, 77, 78, 79, 85, 89, 97, 106, 107, 111, 113, 118 Other frequently reported outcomes included REC in 1920, 26, 28, 64, 65, 68, 70, 73, 74, 75, 78, 79, 85, 94, 96, 97, 111, 113, 118 studies, microbial analysis in 1549, 50, 52, 58, 66, 71, 76, 82, 84, 91, 92, 102, 104, 109, 114 studies, cytokines in 1720, 29, 46, 52, 56, 57, 84, 91, 100, 101, 104, 106, 107, 110, 113, 115, 116 studies, suppuration in 1235, 58, 61, 62, 66, 92, 93, 96, 104, 107, 111, 113 studies, and gingival index (GI) in 1089, 96, 97, 99, 101, 105, 106, 107, 116, 118 studies.

The analysis of the evaluated studies demonstrated that the use of laser therapy for peri-implant tissue is effective in promoting healing and alleviating pain. Low-level laser interventions showed a significant reduction in healing time, facilitating tissue regeneration and promoting a favorable inflammatory response. Patients undergoing this treatment reported a noticeable improvement in pain, evidenced by the assessment scales used in the studies. Furthermore, laser application contributed to faster epithelialization of the affected areas, increasing vascularization and oxygenation of the tissues – essential factors for effective healing.

The results also revealed that laser application reduced complications associated with peri-implant tissue, such as infections and necrosis, reinforcing its role as a valuable therapeutic option. Patients receiving laser treatment not only exhibited improvements in peri-implant tissue conditions, but also reported a better quality of life, reflecting the positive impact of this method in managing these conditions. These findings suggest that laser therapy is a promising approach in the treatment of peri-implant tissue, with significant beneficial outcomes (Supplementary Tables 1–3; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17043500).

Discussion

This scoping review, conducted in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines, aimed to comprehensively map and synthesize the current clinical evidence on the use of laser therapy for peri-implantitis. Although data from 98 clinical studies suggest that laser therapy holds potential as an adjunctive treatment modality, significant methodological limitations and the lack of standardized laser protocols constrain definitive conclusions.

Laser therapy, particularly photobiomodulation (PBM), has emerged as a promising therapeutic option for peri-implantitis management. It employs low-level laser energy to modulate inflammatory responses and promote tissue repair and regeneration.119, 120 It has gained attention due to several advantages over conventional treatments, including significant bactericidal properties and effective implant surfaces decontamination without surface damage.9, 121, 122 Clinically, PBM has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing PD, improving CAL and decreasing BoP when used as an adjunct to conventional treatments.123 Additionally, PBM stimulates bone repair and enhances wound healing.124

Specifically, PBM enhances cellular metabolism by stimulating mitochondrial activity and increasing the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), thereby accelerating tissue repair and reducing inflammation.125 Moreover, it improves local microcirculation, facilitating enhanced delivery of oxygen and nutrients to affected areas, and reduces oxidative stress, leading to accelerated healing and reduced tissue breakdown.126 Despite its growing interest and demonstrated potential, laser therapy’s efficacy in peri-implantitis management remains a subject of debate, with studies presenting mixed outcomes regarding clinical improvements and long-term success. Several laser types, including Er:YAG, Nd:YAG, CO2, and diode lasers, have been utilized either as standalone therapies or in combination with mechanical debridement or antimicrobial agents, highlighting the versatility and adaptability of laser-based treatment approaches.127 Laser therapy experts have identified multiple biological mechanisms through which it exerts its therapeutic effects, promoting tissue regeneration and modulating inflammation in peri-implant tissue.128

This scoping review identified several limitations affecting the strength and consistency of current evidence. A major limitation observed is the small sample sizes across studies, many involving fewer than 50 participants. Small sample sizes inherently reduce statistical power and increase the risk of type II errors, thereby limiting the generalizability of findings.129 Furthermore, a significant portion of existing research consists of case series or non-randomized trials, which inherently provide weaker evidence. Future investigation should prioritize large, diverse populations and employ rigorous study designs, particularly RCTs, to ensure robust and reliable conclusions regarding laser therapy efficacy.130, 131

The influence of demographic factors on treatment outcomes was inconsistently reported. Gender differences, while rarely explored in depth, may affect the progression of peri-implantitis and responses to laser treatment.132 Some evidence indicates that men have a higher risk of peri-implantitis, potentially due to differences in oral hygiene habits or the prevalence of systemic conditions, like cardiovascular diseases.133, 134 Age also plays a critical role, as older patients typically exhibit slower healing rates and compromised immune responses, negatively impacting peri-implantitis treatment outcomes.135 Conditions prevalent in older adults, such as diabetes or osteoporosis, further complicate laser treatment efficacy.136, 137 The level of edentulism also warrants consideration, as peri-implantitis health could differ between partially and fully edentulous patients, yet few studies have explicitly addressed this relationship.138, 139

Another clinical factor limiting definitive conclusions was the short follow-up duration in most studies. Typically, outcomes were assessed within 12 months, providing limited insight into the durability of improvements observed. Some evidence suggests that laser therapy may need to be repeated periodically, particularly in patients with advanced peri-implantitis or systemic health conditions.9 The short-term stability of peri-implant tissues following laser therapy is critical in determining whether this approach offers a sustained solution or merely a temporary intervention.138 Given the chronic nature of peri-implantitis, the stability and sustainability of laser treatment effects are crucial. Future research should extend follow-up periods to assess the lasting benefits of laser therapy both clinically and microbiologically.96

Systemic conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and smoking, significantly influence peri-implantitis progression and treatment outcomes.140, 141 Patients with diabetes often experience chronic inflammation and impaired immune responses, which can potentially reduce the effectiveness of laser therapy.142 Regardless of the modality, the overall success of peri-implantitis treatment is reduced by smoking, which negatively affects wound healing and bone regeneration.143 Although some studies account for these variables, few provide stratified data to isolate the effects of comorbidities on treatment outcomes. Future research should prioritize understanding how laser therapy interacts with systemic health conditions to determine its efficacy in high-risk populations.

Geographic differences, including access to dental care, cultural habits related to oral hygiene, and socioeconomic status, can influence both peri-implantitis prevalence and treatment success.144 The majority of studies reviewed were conducted in Europe, North America or Asia, with limited representation of diverse populations from other regions. Such heterogeneity makes it difficult to generalize findings globally. Cultural and socioeconomic factors have a substantial influence on prevention behaviors, screening participation and treatment outcomes.145

A major challenge in peri-implantitis treatment is the regeneration of lost bone and soft tissues.146 While laser therapy effectively promotes soft tissue healing and has bactericidal effects, its capacity to stimulate significant bone regeneration remains limited.11 Most studies report modest improvements in PD and CAL, but substantial bone regeneration is rarely achieved. Regenerative techniques, such as guided bone regeneration (GBR) or bone grafts, are often used alongside laser therapy to enhance outcomes.147 Combination of these approaches with lasers has not been extensively studied, and their effectiveness remains uncertain. Future research should investigate the synergistic effects of laser therapy with regenerative approaches to determine whether this combination yields superior results in managing advanced peri-implantitis.

Furthermore, laser therapy is frequently associated with conventional treatments. Although conventional therapies can reduce inflammation and control infection, they do not usually provide the same degree of tissue healing and regeneration as PBM, particularly in cases where enhanced soft tissue repair and bone regeneration are required.148 Unlike non-surgical treatments, such as mechanical debridement or the use of antimicrobial agents, which primarily focus on removing bacterial biofilm and reducing infection, laser therapy has bactericidal properties while minimizing damage to surrounding tissues.149 Furthermore, lasers, such as Er:YAG or Nd:YAG, can effectively decontaminate implant surfaces, which is a challenge in traditional treatments where mechanical instruments may struggle to fully access complex implant geometries.150 However, while laser therapy shows promise, its efficacy in comparison to conventional treatments remains under investigation, with mixed outcomes reported regarding long-term success and clinical improvements.

Finally, the lack of standardized treatment protocols significantly hinders the comparison of results across studies.9 There is significant variability in the type of lasers used (Er:YAG, Nd:YAG, CO2, diodes), treatment parameters (wavelength, power settings, pulse duration) and application methods (monotherapy vs adjunctive therapy), which complicates the establishment of evidence-based guidelines.21, 151 This heterogeneity makes it difficult to compare outcomes across studies and draw clear conclusions regarding the most effective laser types. Moreover, there is no consensus on optimal settings, such as the number of treatment sessions or laser exposure duration.11, 131 For instance, some studies report good outcomes with the combined application of Er:YAG lasers due to their precise ablation with reduced thermal damage,16, 152 emphasizing the deep tissue penetration benefits of Nd:YAG lasers.153 Establishing standardized protocols is crucial for improving research consistency, reproducibility and clinical applicability. Future research should aim to create guidelines for laser therapy in peri-implantitis, accounting for laser type, energy settings and treatment intervals.131

Another important consideration is that each type of laser application must be carefully selected and applied according to its specific therapeutic purpose. Photobiomodulation is dedicated to stimulating tissue healing and enhancing regenerative processes, aPDT is aimed at decontamination, while high-energy lasers, such as the erbium family, are primarily used for bone decontamination and implant surface debridement. These modalities can be combined in well-planned treatment protocols to achieve synergistic effects, such as simultaneous decontamination and stimulation of healing. However, their integration must be deliberate and based on solid theoretical knowledge, practical experience and clearly defined clinical objectives, as each has distinct mechanisms of action and treatment parameters. The proper use of these approaches requires specialized training in laser dentistry, and outcomes may vary considerably depending on the operator’s expertise. The lack of detailed reporting on treatment purpose, operator training and exact application protocols in many studies makes it challenging to accurately interpret and summarize the current body of evidence.

Finally, laser therapy demonstrates significant promise as a peri-implantitis treatment. However, addressing methodological limitations, standardizing treatment protocols and investigating demographic and systemic influences are essential steps toward establishing laser therapy as a reliable, effective and long-term therapeutic option. Future research that addresses demographic variability, inconsistent definitions of treatment success, limited information on the duration of therapeutic effects, and regional practice differences will be crucial in establishing robust, evidence-based clinical guidelines for the effective use of lasers in peri-implantitis management.

Limitations

This review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the inclusion of studies with heterogeneous designs, laser parameters and outcome measures complicates direct comparison and synthesis of results. Many studies featured small sample sizes and short follow-up durations, reducing the generalizability and strength of conclusions. In addition, a large proportion of studies lacked standardized reporting on key variables such as patient comorbidities, demographic characteristics or treatment adherence. The lack of consensus on laser protocols (e.g., energy settings, frequency, application duration) further impairs comparability. Finally, language restrictions and limited availability of full texts may have led to the exclusion of relevant studies.

Conclusions

Overall, while laser therapy shows considerable promise as a treatment for peri-implantitis, current evidence is constrained by several limitations. Factors such as small sample size, demographic variability, presence of comorbidities, short follow-up periods, and lack of standardized laser protocols hinder drawing firm conclusions about its long-term efficacy. Future studies should address these limitations through larger, well-designed RCTs with diverse populations, extended follow-up duration and standardized laser treatment protocols. Further research is also required to clarify the influence of comorbidities and geographic factors in treatment success, ultimately enhancing clinical guidelines and therapeutic outcomes.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17043500. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Data extracted from prospective studies.

Supplementary Table 2. Data extracted from retrospective studies.

Supplementary Table 3. Data extracted from RCTs.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.