Abstract

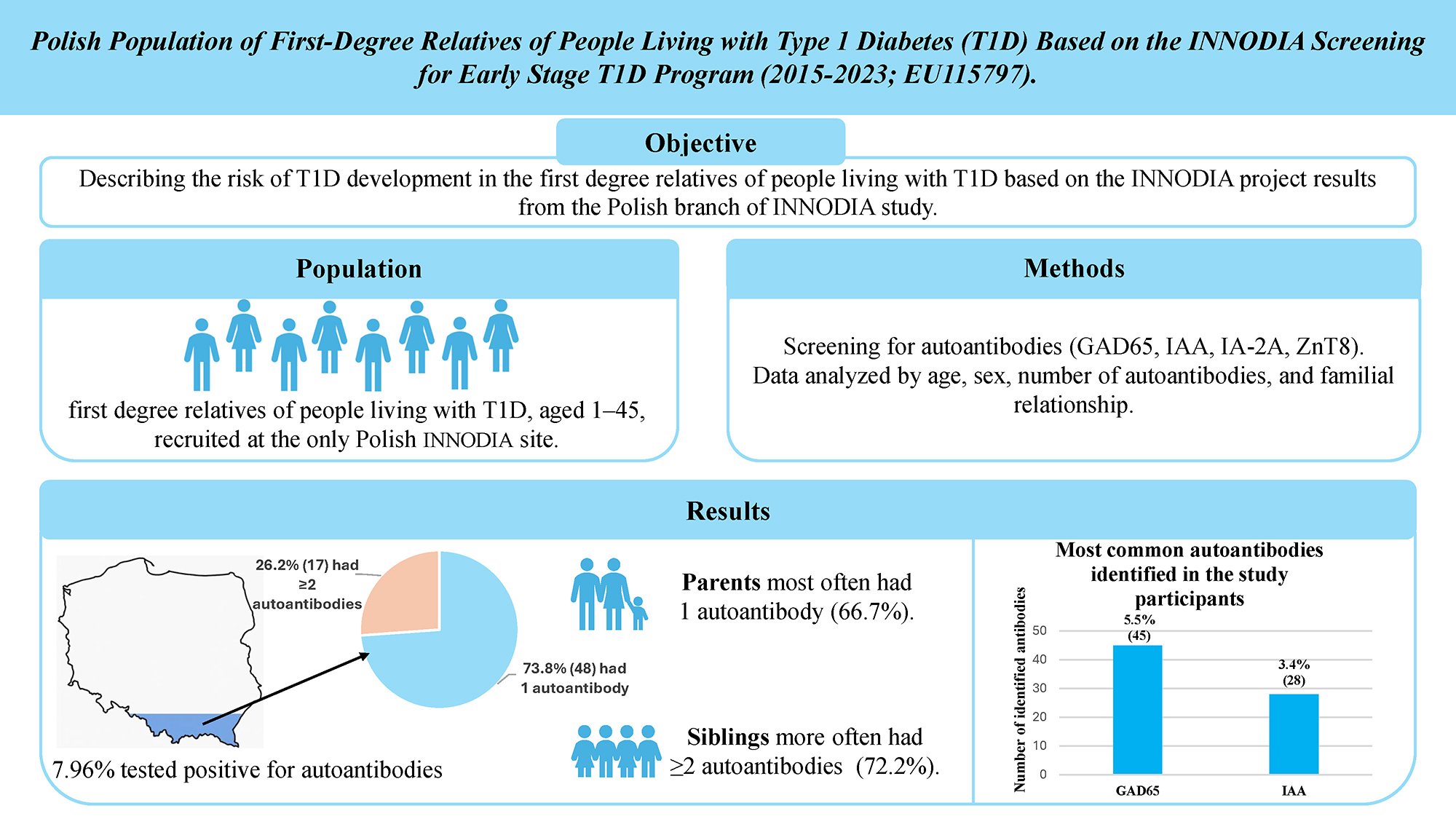

Background. Early identification of individuals at increased risk for type 1 diabetes (T1D) is essential to prevent diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at onset and to facilitate the development of disease-modifying therapies. The INNODIA EU115797 project (2015–2023) conducted a Europe-wide screening of individuals with recent-onset T1D (<6 weeks) and their first-degree relatives (aged 1–45 years).

Objectives. To evaluate the risk of T1D development among first-degree relatives of individuals with T1D, based on data from the Polish INNODIA center at the Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland.

Materials and methods. Data on the incidence of autoantibodies were obtained from the INNODIA project platform. The analysis included first-degree relatives of individuals with T1D, aged 1–45 years, who met the inclusion criteria and were recruited at the Polish center. Samples were collected at the Medical University of Silesia in accordance with the INNODIA protocol. Participants were stratified based on the number of autoantibodies detected (1 or ≥2). The analysis considered age, sex, prevalence of specific autoantibodies (GAD65, IAA, IA-2A, ZnT8), and familial relationship.

Results. Among 817 screened individuals, 65 (7.96%) tested positive for autoantibodies (AA): 48 (5.88%) had 1AA and 17 (2.08%) had ≥2AA. The highest prevalence was observed in the 10–23-year age group (27.7%, 18/65). In this subgroup, 11.04% (18/163) were autoantibody-positive, whereas prevalence in other age groups (1–9, 24–36, 37–40, and 41–45 years) ranged from 5.98% to 8.97%. GAD65 (5.51%) and IAA (3.43%) were the most frequent autoantibodies. Individuals with 1AA were predominantly parents (32/48; 66.7%), while ≥2AA were more common among siblings (13/17; 72.2%). During follow-up, 2 participants progressed to stage 3 T1D.

Conclusions. In the Polish cohort of the INNODIA study, autoantibodies were detected in 7.96% of first-degree relatives of individuals with T1D. Early screening is crucial for accurate risk stratification, guiding the development of therapeutic interventions and reducing the risk of severe complications at disease onset.

Key words: autoantibodies, diabetes mellitus type 1/diagnosis and immunology, mass screening/methods, autoimmune diseases/diagnosis, autoimmune diabetes mellitus

Background

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is the most common type of diabetes in the European pediatric population, with nearly 129,000 new diagnoses each year globally in children and adolescents under 20 years of age.1, 2 According to the T1D Index, the estimated number of people living with T1D in 2024 was 9.4 million, and with the continued rise in its incidence, this number is expected to reach 16.4 million by 2040 ((Type 1 Diabetes Index; https://www.t1dindex.org).

Thanks to ongoing T1D research, remarkable progress has been made in staging the early phases of the disease and refining its definitions. It is now well established that autoantibodies, which serve as markers of T-cell-mediated β-cell destruction, may appear years before the clinical onset of T1D. Identification of T1D-related autoantibodies – such as GAD65 (glutamic acid decarboxylase), IAA (insulin autoantibody), IA-2A (islet antigen-2 antibody), and ZnT8 (zinc transporter-8 antibody) – in combination with glucose metabolism monitoring enables classification of preclinical stages of T1D: stage 1 (≥2 autoantibodies and normoglycemia), stage 2 (≥2 autoantibodies and dysglycemia) and stage 3 (≥2 autoantibodies and clinical onset).3, 4, 5, 6 The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) 2024 Guidelines provide more detailed subdivision of these stages, reflecting advances in understanding of the disease.5

In recent years, initiatives to identify individuals in the early stages of T1D have laid the foundation for ongoing screening efforts to reduce the incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at T1D onset, as well as to minimize short and long-term morbidity, mortality, prolonged hospitalization, weight loss, and psychological burden associated with T1D onset.7 These endeavors also provide participants with the opportunity to enroll in clinical trials investigating disease-modifying therapies aimed at delaying the onset of T1D. Islet autoantibody testing has proven to be an effective method for detecting early-stage T1D and may be preferred over genetic testing due to lower participant dropout rates and its predictive value in stratifying the rate of progression to stage 3 T1D once autoantibodies are developed.5 Moreover, genetic risk is frequently perceived as abstract and difficult for parents to fully understand and accept.8 In accordance with the most recent ISPAD guidelines, population-based screening for T1D is optimally performed between 3 and 5 years of age, with maximal sensitivity achieved by 2 examinations at 2 and 6 years of age.5 When screening is deferred until adolescence, the preferred time points are 10 and 14 years of age.5 However, it should be emphasized that despite the ongoing efforts to integrate T1D screening into national healthcare systems, still only a minority of countries currently maintain nationwide programs. In Poland, the majority of children who present with – or are likely to develop – stage 3 T1D have not undergone prior T1D screening. Therefore, if the standard, age-based screening windows cannot be met, it is reasonable to offer T1D screening independently of a child’s age.

In 2015 the INNODIA (now an international non-profit organization, formerly a European-based public-private partnership) launched the project (EU115797) titled Translational Approaches to Disease-Modifying Therapy of Type 1 Diabetes: An Innovative Approach Towards Understanding and Arresting Type 1 Diabetes.9 The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia (Katowice, Poland; approval No. KNW/0022/KB1/25/I/17 issued on May 16, 2017). As the largest program of its kind at the time, this European-wide initiative conducted a screening of individuals with newly diagnosed T1D (diagnosed less than 6 weeks prior) as well as first-degree relatives of individuals living with T1D. The study ran from November 1, 2015, to October 31, 2023, and included participants from 13 European countries, including Poland with the reference site at the Medical University of Silesia, which became an accredited clinical trial site. The project was carried out under the framework of the Innovative Medicines Initiative – Joint Undertaking (IMI-JU) and involved a global partnership between academic researchers and industrial partners, all working towards combating T1D.9

It has been well established that first-degree relatives of individuals with T1D face a markedly higher (up to 15 times) risk of developing T1D than the general population, with the prevalence of T1D in the first-degree relatives equal to 5% by the age of 20, compared to 0.3–0.4% in the general population.5, 10, 11, 12

Children of mothers with T1D have a 1.3–4% risk of developing the disease, whereas children of fathers with T1D have a higher risk of 6–9%. In siblings of individuals with T1D, the lifetime risk is estimated at approx. 6–7%.10, 11, 12 Relatives of individuals with T1D should certainly be included in early screening; however, population-wide screening is also warranted, as it is reasonable to state that everyone is at risk of developing T1D. This is supported by evidence showing that approx. 90% of individuals with recent-onset T1D have no known family history of the disease.5

Objectives

The aim of this study was to describe and characterize the risk of type T1D development in the Polish population, based on data from the INNODIA screening project, which focused on first-degree relatives of individuals with T1D.

Materials and methods

Between 2018 and 2023, all first-degree relatives (aged 1–45 years) of individuals either newly diagnosed with T1D or already receiving care at the Outpatient Department of Children’s Diabetology and Lifestyle Medicine at the Independent Public Clinical Hospital No. 6 of the Silesian Medical University in Katowice (Upper Silesian Child Health Centre) were invited to participate in the INNODIA study conducted at the Medical University of Silesia.

In addition to serving as an INNODIA clinical site, this center is accredited as a certified SWEET (Better control in Pediatric and Adolescent diabeteS: Working to crEate CEnTers of Reference) reference center and participates in international projects, including the European Action for the Early Diagnosis of Early Non-Clinical Type 1 Diabetes for Disease Interception (EDENT1FI).13

To be enrolled, participants were required to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 1. Eligible individuals were invited for a screening visit, which included a blood test for the presence of T1D-specific autoantibodies (GADA, IAA, IA-2A, ZnT8A). Three autoantibodies (GADA, IA-2A and ZnT8A) were analyzed at the PEDIA (Pediatric Diabetes Research Group) laboratory at the University of Helsinki, Finland, while IAA was measured using a specific radiobinding assay.14

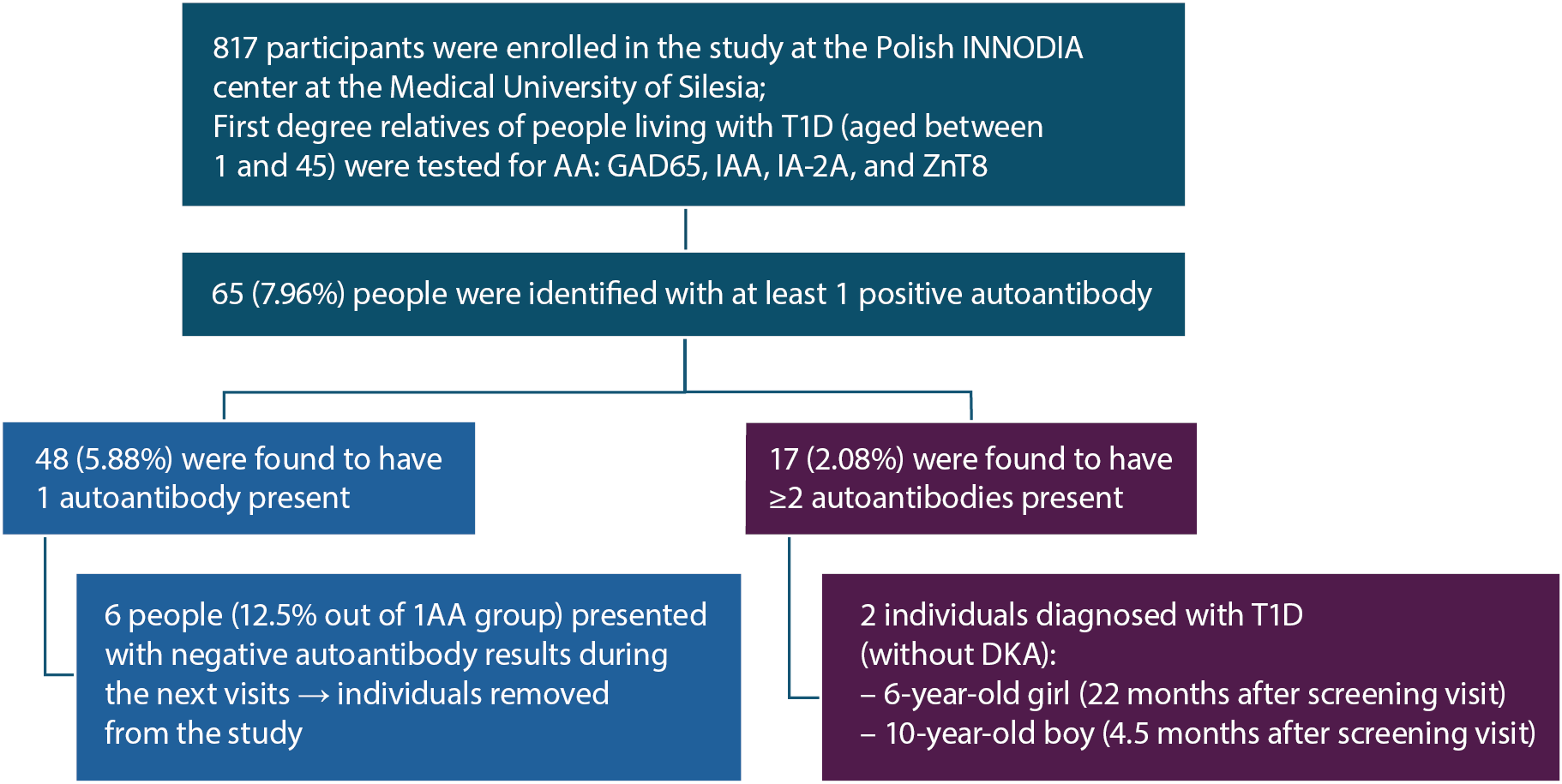

If participants tested positive for autoantibodies (AA), they were assigned to either the Unaffected Family Member (UFM) or People at Increased Risk (PIR) group, depending on the year of enrollment. Individuals who were screened up until the July 20, 2022, were assigned to the UFM group. If the screening resulted in at least 1 positive autoantibody, participants continued in the study and followed a specific visit schedule to ensure they received specialized medical care. Consecutively, every patient enrolled in the study after July 20, 2022, was assigned to the PIR group. In this case, further medical care was provided only if the individual was found to have at least 2 autoantibodies present (Figure 1).

Participants in both the UFM and PIR groups received medical care through regular follow-up visits, which included eligibility screening, medical history review, anthropometric measurements, assessment of glycemic control (oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)), immunological testing, and biobanking. Detailed schedule for visits and performed tests are presented in the Table 2, Table 3. If required, any additional tests were performed in order to provide the best possible care following then-current ISPAD guidelines. At the time of the INNODIA study, the clinical site at the Medical University of Silesia was not conducting any kind of trials aimed at people at an early stage of T1D. Therefore, participants were not offered enrolment to the clinical trials but were informed of the potential opportunities to join clinical trials at other sites. All participants received education on the symptoms of T1D onset and the disease management, which contributed to the prevention of DKA development at the onset of symptomatic T1D.

Unfortunately, data on potential reasons for reluctance or concerns about participating in and continuing the study were not collected, as well as mental health assessment was not performed; therefore there were no data enabling assessment of the direct impact of screening on individuals’ mental wellbeing. This illustrates the shift in perception of the T1D screening process and the movement towards a holistic and patient-centered model that incorporates psychological wellbeing assessment as a key component.

However, it is important to note that most participants – being First-degree relatives of individuals living with T1D – already had substantial disease awareness and understanding, which may have influenced how they perceived and accepted the final diagnosis. Nonetheless, any individual in need of psychological support was offered assistance from a qualified psychologist at the Medical University of Silesia site.

Results

Among 817 first-degree relatives of individuals with T1D, 7.96% (n = 65) tested positive for at least 1 autoantibody. Of these, 5.87% (n = 48) had a single autoantibody, corresponding to an estimated 15% risk of developing T1D within 15 years, with most progression occurring within 2 years of seroconversion. The remaining 2.08% (n = 17) had ≥2 autoantibodies, associated with a 44% risk of progression to stage 3 T1D within 5 years and an almost 100% lifetime risk.5, 6, 10

Among the 48 individuals with a single autoantibody, 6 (12.5%) subsequently reverted to seronegative status. In 5 cases the autoantibody was GAD65, and in 1 case IAA. These individuals represented a wide age range (3, 8, 15, 17, 34, and 39 years), with no discernible pattern related to age at seroreversion. Four were siblings and 2 were parents of a child with T1D.

Additionally, 15 of the 48 participants with a single autoantibody were initially recruited as PIR rather than UFM. At that time, eligibility for follow-up required the presence of at least 2 autoantibodies. Since these participants did not meet the follow-up criteria and no subsequent data regarding their autoantibody status were available, the true incidence of transient autoantibody positivity may be underestimated. Over the course of the study, 2 children progressed to symptomatic stage 3 T1D. In both cases, DKA was not observed at the time of onset (see Figure 2 for details).

Autoantibody identification stratified by age

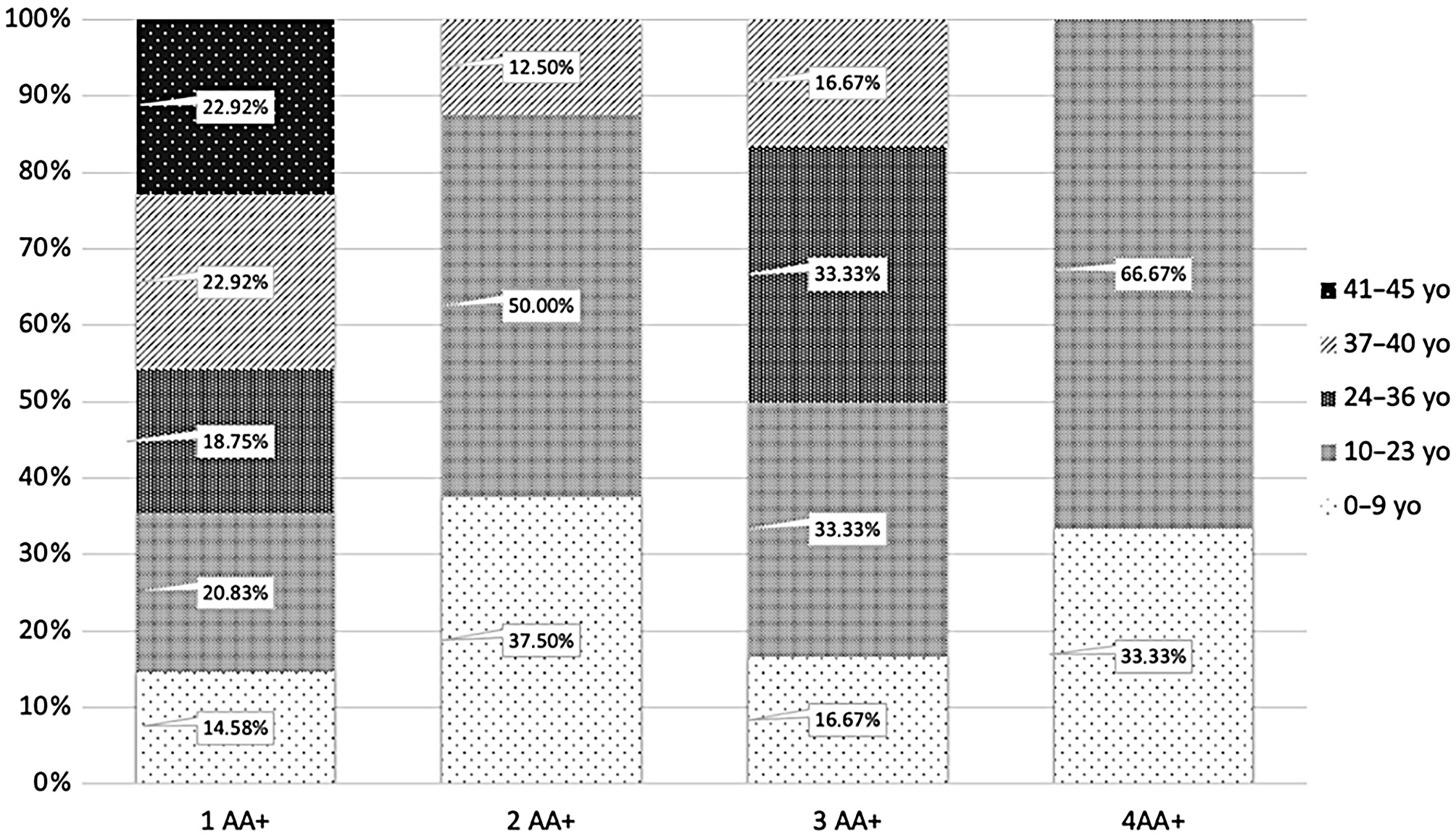

Individuals were divided into 5 age groups: 0–9, 10–23, 24–36, 37–40, and 41–45 years, each accounting for approx. 20% of the total PIR and UFM study population (n = 817). The largest group was the 41–45 age range (184 participants, 22.52%), while the least populous group was the 37–40 age range (146 participants, 17.75%) (Table 4).

Most participants with positive autoantibodies had only 1 autoantibody (73.85% of the total AA+ group; n = 48). Seventeen (26.15%) were found having 2 or more autoantibodies, with 8 (12.31%) having 2 autoantibodies, 6 (9.23%) having 3 autoantibodies and 3 (4.62%) with 4 autoantibodies. The majority of AA+ individuals were aged 10–23, accounting for 27.69% of all AA+ (18 of 65).

Consequently, 11.04% (18 of 163) of participants in this age group had at least 1 autoantibody, while the percentage for other age categories ranged from 5.98% to 8.97%. The 10–23 age group also had the highest prevalence of 2 autoantibodies (2.5%, n = 4) and 4 autoantibodies (1.2%, n = 2). There were 2 individuals with 3 autoantibodies (1.2%, n = 2) both for the 10–23 and 24–36 age category. People between the age 10–23 accounted for 50.00% (n = 4) of cases with 2 autoantibodies, for 33.33% (n = 2) with 3 autoantibodies and for 66.67% (n = 2) with 4 autoantibodies.

There is a predominance of younger individuals with 2 autoantibodies, which can be observed in Figure 3. However, this pattern was not observed in the group with only 1 autoantibody. In contrast, participants aged 37–45 accounted for approx. 46% (n=22) of the 1AA group. Additionally, 20.83% (n = 10) of individuals with 1 autoantibody were between 10 and 23 years old, while 18.75% (n = 9) were aged 24–36. The lowest percent of people with 1 autoantibody was in the 0–9 age group (14.58%, n = 7). Single-autoantibody cases demonstrated a more balanced age-profile than cases with 2 autoantibodies; however, the aspect of a very small sample must be taken into consideration (Figure 3). In the 37–40 age group, 7.59% of participants had 1 autoantibody, while the percentage for 2 autoantibodies and 3 autoantibodies was 0.69% in both cases, and none was found having 4 autoantibodies. Although there is a slight predominance of positive autoantibodies in younger individuals, it is important to note that autoantibodies were detected in all age groups, supporting the rationale for including adults (>18 years) in T1D screening programs.

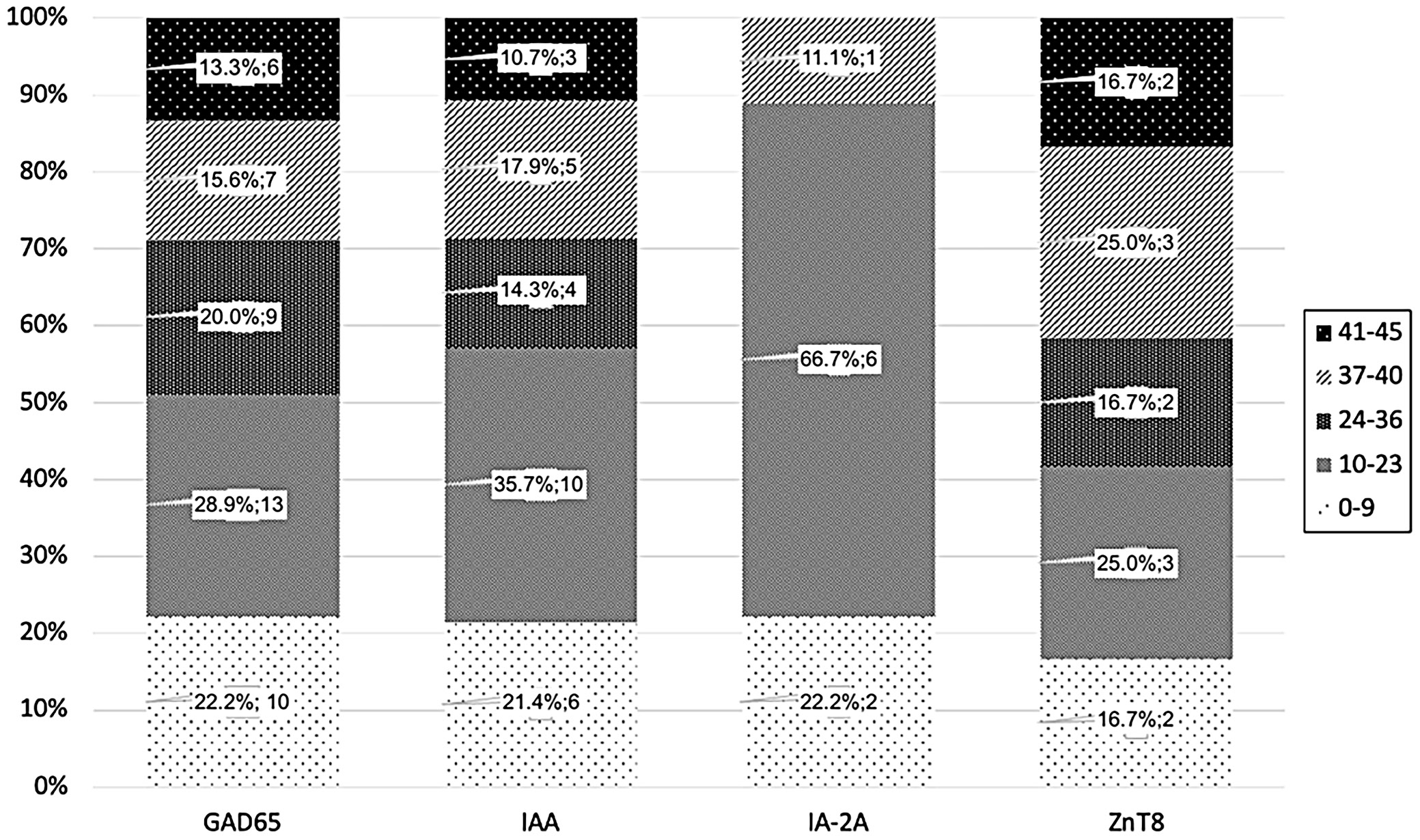

Figure 4 shows that the occurrence of specific autoantibodies is in overall similar across age groups. However, 66.7% (n = 6) of IA-2A cases were in the 10–23 age group, while this group accounted for 25% (n = 3 for ZnT8) to 35% (n = 10 for IAA) of cases for other autoantibodies. Certainly, due to the small sample size, no firm conclusions can be drawn at this point.

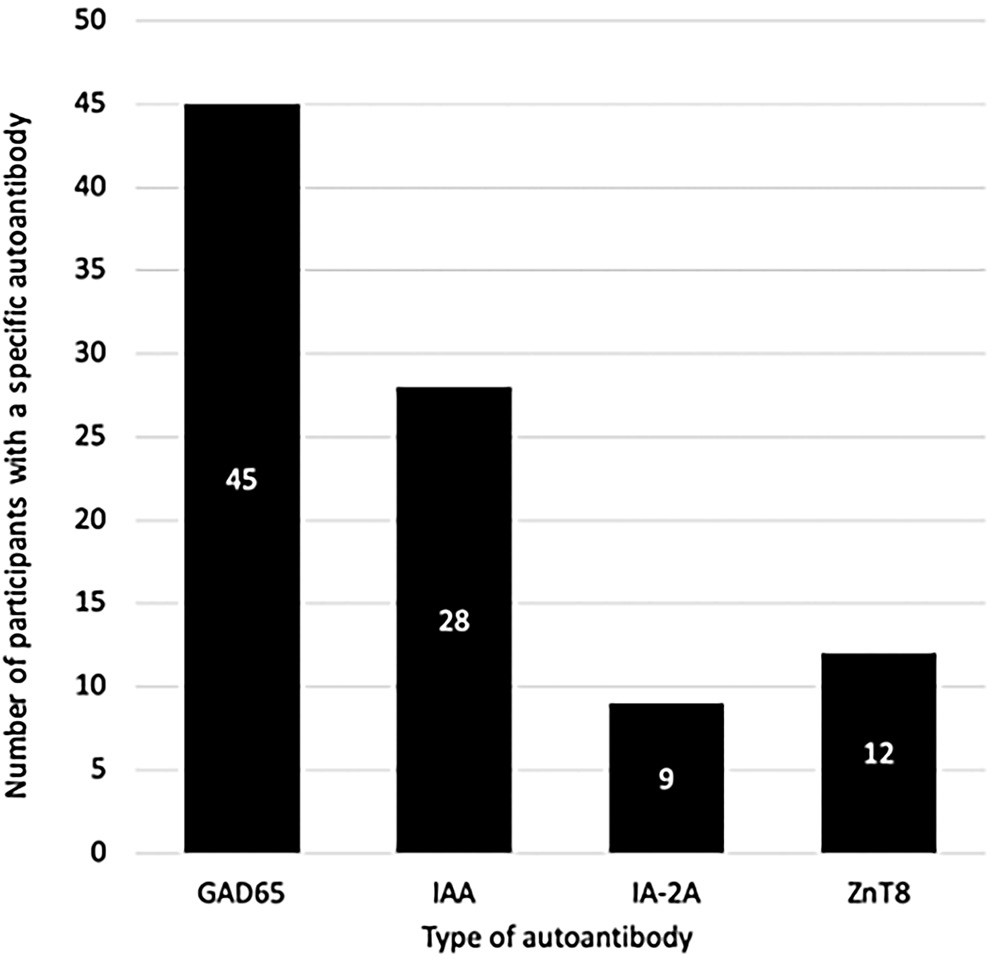

Autoantibody identification stratified by sex

As noted, 65 participants (7.96%) had at least 1 autoantibody (Figure 2). GAD65 was the most common, found in 69.23% (n = 45) of all AA+ cases and 5.51% of all screened (Figure 5). IAA was found in 43.08% (n = 28; 3.43% of UFM and PIR), followed by ZnT8 in 18.46% (n = 12; 1.47% of UFM and PIR) and IA-2A in 13.85% (n = 9; 1.10% of UFM and PIR).

The stratification of autoantibodies by sex (Figure 6) mirrored the overall incidence, with women marginally higher (53.85%, n = 35) than men (46.15%, n = 30), which is consistent with the study’s overall sex ratio (56.55% women). In general, 7.58% of women (n = 35) in the study had positive autoantibodies, compared to 8.45% (n = 30) of men. Therefore, although a greater number of women tested positive for autoantibodies, the detection rate relative to the number of participants was higher in men. Women also represented the majority of those with 1 autoantibody (60.42%, n = 29). In contrast, the majority of those with ≥2 autoantibodies were male: 62.50% (n = 5) for 2 autoantibodies, 66.67% (n = 4) for 3 autoantibodies and 66.67% (n = 2) for 4 autoantibodies. Despite predominance of women in the study, GAD65 incidence was similar: 5.19% (n = 24) in women and 5.92% (n = 21) in men. IAA was more frequent in men (4.23%, n = 15) than women (2.81%, n = 13), while IA-2A was even 4 times more frequent in men (1.97%, n = 7) than women (0.43%, n = 2). Again, no definite conclusions can be drawn about the prevalence of specific autoantibodies across age groups due to the limited number of cases in each group.

Participants with 2 or more autoantibodies

Type 1 diabetes screening enables to identify individuals at an early stage of T1D. Those in stage 1 face a nearly 100% lifetime risk of progressing to stage 3 T1D.5, 6, 10, 15 Given the importance of early detection and monitoring, data for participants with multiple (2 or more) autoantibodies were analyzed separately (Table 5).

Seventeen participants (1.96% of the UFM and PIR group, n = 817) had multiple (2 or more) autoantibodies, representing 26.15% of all those with AA+. These individuals were classified as stage 1 T1D, as all had normoglycemia, and back then no continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) was required for them.

In both the AA+ group and the ≥ 2AA group, GAD65 and IAA occurred with the highest prevalence. For people with ≥ 2 autoantibodies, IA-2A was 3rd most frequent (9 out of 17), while in the overall AA+ group, it was ZnT8.

Six out of the 17 participants with ≥ 2 autoantibodies were female, with age ranging from 1 to 37 years (1, 6, 11, 13, 35, 37). The remaining 11 participants were male, with age ranging from 2 to 40 years (2 (n = 2), 3, 10, 11 (n = 2), 12, 12, 15, 33, 40).

To observe the co-occurrence of autoantibodies and their combinations in the study participants, all configurations and their frequencies are presented in the Table 6.

Follow-up diagnoses of stage 3 T1D in study participants

Within this group, a 6-year-old girl and a 10-year-old boy progressed to stage 3 T1D, both without developing DKA at diagnosis (Table 7).

The 6-year-old girl tested positive for 2 autoantibodies – GAD65 and IAA – at screening visit and progressed to stage 3 T1D after 22 months. At her last follow-up visit, 53 days before clinical onset, there were no signs of dysglycemia (HbA1c: 36.64 mmol/mol). She began regular visits at the Diabetes Outpatient Department and, 21 months post-diagnosis, is being treated with insulin injections twice a day. Her current HbA1c is 5.2%, with a time in range (TIR) of 93%.

The 9-year-old boy, positive for GAD65, IAA and IA-2A at screening, progressed to stage 3 T1D within only 4.5 months. IA-2A presence, high autoantibody levels and high-affinity screening have been shown to predict rapid progression to clinical T1D.9, 10 Similarly to the 6-year-old girl, his follow-up visit took place 50 days before disease onset and presented no dysglycemia (HbA1c: 36.62 mmol/mol). Now 13 years old, he attends follow-up visits, using an insulin pump (0.8 units/h), with a TIR of 58% and an HbA1c of 7.4% At times, he may question or be reluctant to follow his treatment plan, which is not uncommon for individuals his age.

Autoantibody profiles stratified by family relationship

The largest group of participants were parents of individuals with T1D (60.59%, 495), followed by siblings (38.19%, 312) and children of parents with T1D (4.41%, 36). It is important to note that individuals may be counted more than once if they fit multiple categories. Among children with a parent diagnosed with T1D, 8.33% (3/36) were positive for at least 1 autoantibody, while for parents of children with T1D it was 7.27% (36/495). The highest percentage of autoantibodies was found in siblings, at 9.62% (30/312).

Among those with 1 autoantibody, 66.67% (n = 32) were parents of children with T1D, 35.42% (n = 17) were siblings and 4.17% (n = 2) were children of a parent with T1D. The highest incidence of 2 autoantibodies was found in siblings of individuals with T1D, who accounted for 75% (6 out of 8) of all individuals with 2 autoantibodies.

Three autoantibodies were only found in siblings (n = 4, 66.67%) and parents of children with T1D (n = 3, 50.00%), while 4 autoantibodies were observed exclusively in 3 individuals, all of whom were siblings of a person with T1D.

When examining autoantibody prevalence by the familial relationships, GAD65 was most common in both siblings and parents. Of the 45 individuals with positive GAD65, 53.33% were siblings and 48.89% were parents. Only 4.44% were children of parent with T1D. It is important to consider that individuals may have multiple familial connections to an individual with T1D.

Similarly, IAA was most often found in siblings (53.57%; n = 15) and parents of individuals with T1D (42.86%; n = 12). Interestingly, 88.9% (n = 9) of those with IA-2A were siblings and 11.10% (n = 1) were parents. No cases of IA-2A were observed in children of T1D parents. The same pattern was seen for ZnT8, which was found only in siblings (50.00%; n = 6) and parents (66.67%; n = 8).

Discussion

The Polish INNODIA cohort provides insight into T1D development risk in the first-degree relatives of people living with T1D. Among the 65 participants with autoantibodies, 73.8% (n = 48) had 1 positive autoantibody, with GAD65 and IAA being most common. Despite the smaller sample size (n = 817), the findings are consistent with the broader INNODIA dataset (n > 4,400) and with the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Pathway to Prevention Study (TN01), a USA-based consortium (n > 250,000), both of which focus on screening first-degree relatives of individuals with T1D.10, 16

Although both studies were still ongoing as of 2022 and had not yet reported final results, they demonstrated similar patterns in autoantibody prevalence, with GAD65 and IAA being the most frequently observed.16 In the Polish INNODIA cohort, 7.96% of first-degree relatives tested positive for at least 1 autoantibody, compared to 5.00% in TrialNet TN01. The prevalence of ≥2 autoantibodies in the Polish cohort (2.08%) was comparable to that reported in the overall INNODIA (2.6%) and TrialNet TN01 (2.5%) studies.10, 16

These similarities suggest that autoantibody patterns in the Polish data align with those in larger international cohorts, though caution is needed due to the limited sample size. Despite differences in number of participants and regions, these studies indicate consistent T1D risk in first-degree relatives across populations. While Poland lacks a national T1D screening program, a study performed by the Medical University of Bialystok reported that 7.78% of 3,575 children screened had at least 1 autoantibody, with markedly higher prevalence of a single autoantibody (6.60%; n = 236) compared to multiple autoantibodies (1.17%, n = 42). It is important to note, however, that this study focused on children aged 1–9 years, a younger cohort than that examined in the INNODIA study, and included a broader population, not limited to first-degree relatives.17

Type 1 diabetes mellitus screening in clinical practice enables the detection of early-stage disease, reducing the incidence of DKA and facilitating enrollment in clinical trials for disease-modifying therapies. Early diagnosis through screening reduces DKA rates at onset to below 5%, whereas in Poland, 30–40% of children with newly diagnosed T1D present with DKA.5, 15, 18, 19, 20

Prior screening, metabolic staging and education help eliminate clinical differences between individuals with and without a family history of T1D.18, 21 In the Fr1da study, participants who did not receive early intervention – including education – had higher HbA1c levels and more frequent hospitalizations compared with those who did.7 Similarly, individuals with a family history had lower HbA1c levels (9.3% vs 10.6%) and fewer cases of severe ketonuria compared to those without a family history. These studies emphasize the importance of awareness and early detection through screening and proper education.8

In the Polish INNODIA study, most AA-positive individuals (73.8%, n = 48) presented with a single autoantibody. Although their risk of progressing to T1D is comparatively lower – with approx. 50% of children showing transient positivity – they still require careful monitoring, particularly younger individuals and those within the first 2 years of seroconversion.6

Type 1 diabetes screening is a complex process, with various factors potentially influencing the decision to participate such as fear of positive result or inability to prevent T1D.22, 23 To improve participation, it is essential to address the emotional challenge associated with screening and to provide appropriate psychological support, particularly for individuals experiencing anxiety about the results. Providing support and educating individuals on T1D, its autoimmune causes, symptoms, and the importance of early detection can reduce stress and encourage continued involvement. A balanced approach combining medical information and emotional support is a key to motivating participation.

Limitations of the study

In Poland, over 1/3 of children newly diagnosed with T1D present with DKA.18, 19 The INNODIA study, which focused on first-degree relatives of individuals with T1D, does not fully represent the general population. Accordingly, broader screening and early detection initiatives should be implemented to encompass the general public. A proactive approach, emphasizing early recognition of symptoms and timely support, should be incorporated into care protocols for individuals at the earliest stages of T1D. Additional analyses, such as the influence of birth order and sibling sex, may provide further insights, although the relatively small sample size in this study limits the reliability of such conclusions.

Conclusions

Analysis of the Polish INNODIA results reveals a similar occurrence of autoantibodies in first-degree relatives of people with T1D when compared to other European countries. Early detection of T1D is an evolving initiative that offers valuable medical care not only to relatives of people living with T1D but also to the broader population.

Although the process is complex and optimal strategies are still under development, substantial progress has been achieved since the early phases of the INNODIA screening program. These advances provide a solid foundation for the potential implementation of national screening initiatives, with the ultimate goal of improving patient care.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are openly available in the Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15574493.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.