Abstract

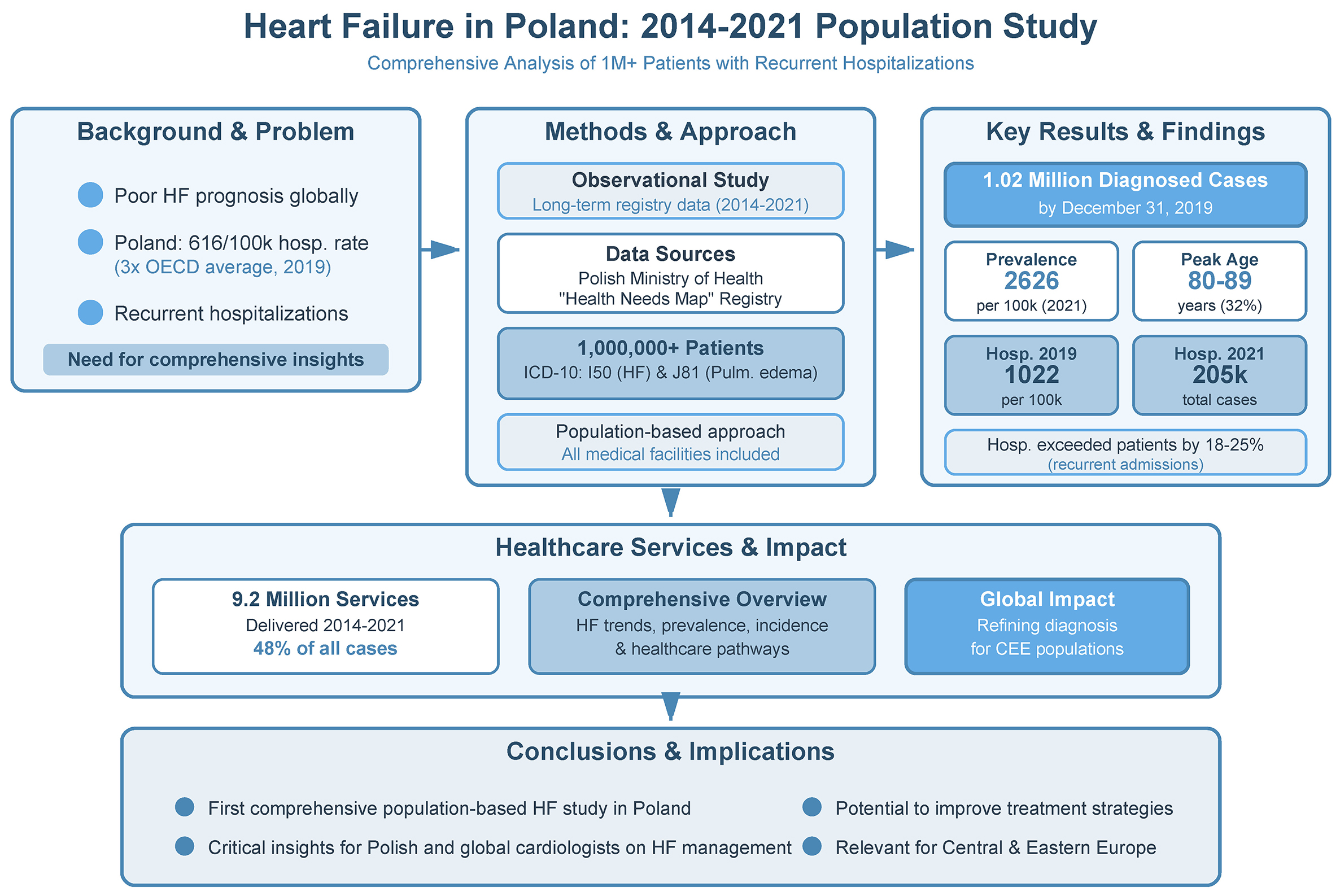

Background. Heart failure (HF) is marked by a poor prognosis, heightened mortality risk, and recurrent hospitalizations. Poland consistently ranks among the highest of all Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, with a hospitalization rate of 616 per 100,000 citizens in 2019 – nearly 3 times the 34-country average.

Objectives. This study aims to provide essential insights into the management of HF patients in Poland, with a particular focus on individuals experiencing recurrent hospitalizations, over the period 2014–2021.

Materials and methods. This observational study analyzes long-term registry data from the Polish Ministry of Health and the Health Needs Map. It includes more than 1,000,000 patients diagnosed with HF (ICD-10: I50) or pulmonary edema (ICD-10: J81), treated across all medical facilities operating under a uniform national healthcare system. This study inherently employs a population-based approach, encompassing all medical facilities that treat patients with these ICD-10 codes.

Results. Here, we present data on HF prevalence, incidence, and the healthcare pathway. The number of diagnosed HF cases in Poland increased to 1.02 million by December 31, 2019. In 2021, the standardized HF prevalence rate reached 2,626 per 100,000 population, with the highest prevalence observed in individuals aged 80–89 years (32%). Heart failure hospitalizations (HFH) in 2019 were 1022 per 100,000, decreasing to 205,000 in 2021. Notably, the number of hospitalizations exceeded the number of patients receiving treatment by 18–25%. Between 2014 and 2021, more than 9.2 million healthcare services were recorded, accounting for 48% of all HF-related encounters.

Conclusions. This study, relevant to both Polish and international cardiologists, provides a comprehensive overview of HF trends and associated risks, offering insights that may help refine diagnosis and treatment strategies in Central and Eastern European populations.

Key words: heart failure, hospitalization, registries, epidemiology in Poland, population surveillance

Background

Heart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome characterized by a poor prognosis and a high risk of death and heart failure hospitalizations (HFH).1 In Poland, the overall number of patients with HF has been systematically increasing.2, 3 Poland consistently ranks among the highest of all Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, with a HFH rate of 616 per 100,000 citizens in 2019 – nearly 3 times the 34-country average of 220.4 This rate has been rising since 2009, in contrast to global trends showing a decline.

Beyond its epidemiological magnitude, HF represents a major and growing public health challenge in Poland, exerting a substantial clinical, organizational, and economic burden on the healthcare system.1 The persistently high rates of hospitalization reflect not only the aging of the population and improved survival after acute cardiovascular events, but also a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, multimorbidity, and suboptimal implementation of evidence-based therapies across the continuum of care.1, 2, 3 Recurrent HF hospitalizations are associated with accelerated disease progression, impaired quality of life, and markedly increased mortality risk, underscoring the vicious cycle of decompensation and readmission.1, 2, 3 In this context, the unfavorable Polish trends, diverging from those observed in many other OECD countries, highlight an urgent need for more effective prevention strategies, earlier diagnosis, optimized outpatient management, and coordinated, system-level interventions aimed at reducing HF-related morbidity and mortality.1, 2, 3

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to generate comprehensive insights into the management of patients with HF in Poland, with particular emphasis on individuals experiencing recurrent hospitalizations. By analyzing data from 2014 to 2021, the study characterizes temporal trends, treatment patterns and healthcare utilization within this high-risk population. The findings aim to inform clinical practice, optimize resource allocation, and support the development of targeted strategies to reduce hospital readmissions and improve outcomes in HF care in Poland.

Materials and methods

Description of the studied population

This study is an observational long-term registry analysis using data from the Polish Ministry of Health spanning from 2014 to 2021. The study population reflects a diverse and extensive national cohort. Data obtained from the National Health Fund included patients diagnosed with HF (ICD-10: I50) and pulmonary edema (ICD-10: J81). A total of more than 1,000,000 patients with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF were included in the analysis, the majority of whom were treated within a single type of medical service. Given the volume of cases, the study is population-based and encompasses all medical facilities providing care for conditions classified under ICD-10 codes I50 and J81.

Definitions of analyzed endpoints

Heart failure recorded as the main diagnosis in primary healthcare (PHC), outpatient specialist care (OSC), or hospital treatment indicates that the ICD-10 code for HF (I50 or J81) was listed as the first diagnosis (the primary reason for admission). In contrast, “HF overall” denotes cases in which the HF diagnosis appeared in the medical record as an additional or secondary condition. Hospitalization was defined as any inpatient stay with the relevant ICD-10 codes, including a diagnosis of HF. Heart failure hospitalization referred specifically to inpatient admissions directly associated with exacerbation or decompensation of HF. Hospital treatment, by contrast, denoted any other hospitalization occurring in patients with an HF diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

All described data regarding the healthcare services was derived from the following sources: 1) data provided by the Polish Ministry of Health specifically for the authors of this report; 2) Health Needs Map for the years 2022–20265; 3) analysis of the health problem of HF included in the Systemic and Implementation Analyses Base3; 4) statistics from the Polish National Health Fund; 5) selected data from the www.ezdrowie.gov.pl portal. All data was delivered anonymously, ensuring the highest level of data protection. A descriptive analysis was undertaken employing numerical values and/or percentages within each group, including the data presented as counts per 100,000 patients in the population.

Based on available data for pre-pandemic years (2014–2019), we performed a linear trend analysis, using the least-squares method, forecasting the trend for 2020–2021. Based on this analysis it is possible to compare the forecasted values with the data available for 2 pandemic years (2020–2021). The p-values for linear trend based on pre-pandemic data were also estimated. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA).

Results

Epidemiology: prevalence and incidence of HF

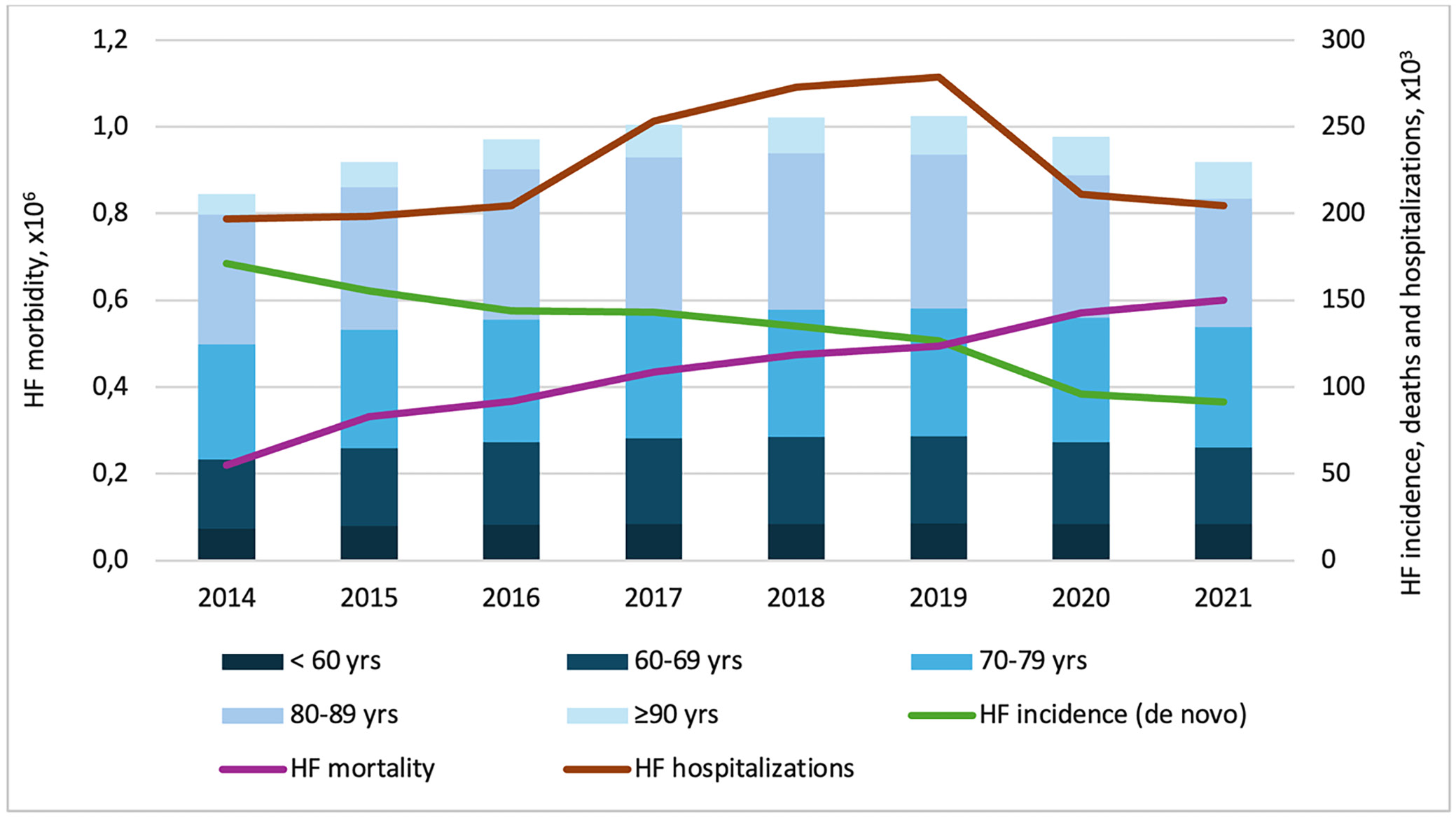

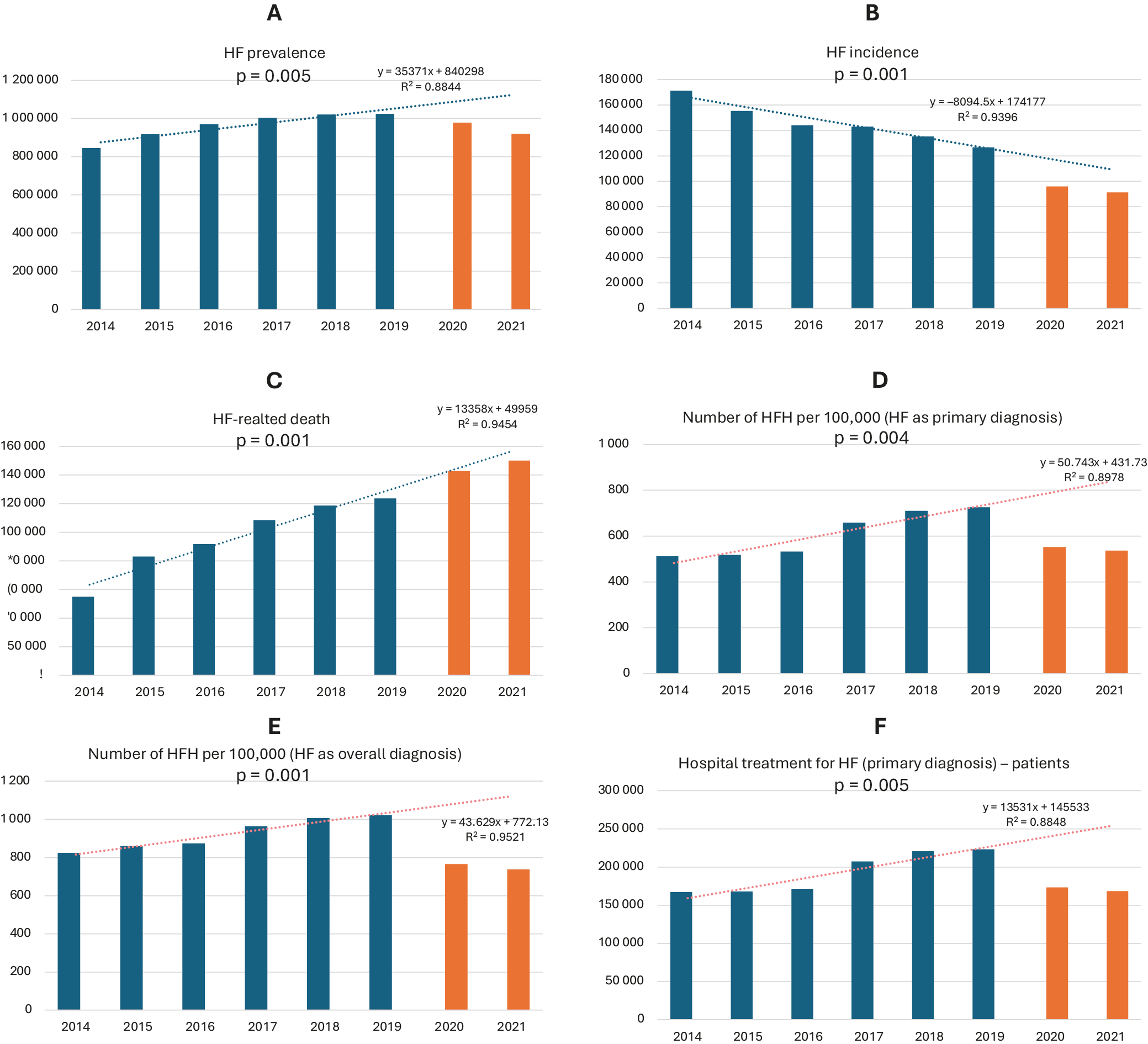

Figure 1 summarizes HF morbidity, incidence, and hospitalizations, with colored bars depicting trends across calendar years and columns representing specific age groups. According to the latest Ministry of Health data, the number of diagnosed HF cases in Poland increased steadily from 2014 to 2019, reaching 1.02 million by December 31, 2019. Across the years analyzed, we observed a significant upward trend in HF prevalence accompanied by a simultaneous and significant decline in HF incidence (de novo HF) (Figure 2A,B). During this period, de novo HF diagnoses decreased notably, with 127,000 cases reported in 2019 – representing a 26% reduction compared with 2014. Conversely, the total number of HF-related deaths increased markedly, reaching 124,000 in 2019 – nearly equaling the number of new HF cases (Figure 2B–D). In 2020–2021, although new HF diagnoses declined, HF-related deaths continued to rise, leading to a reduction in registered morbidity (Figure 2C). The current analysis shows that the HF prevalence rate in 2021 was 2,413 per 100,000, increasing to 2,626 per 100,000 after standardization for age, sex, and place of residence. The highest prevalence was observed among individuals aged 80–89 years (32%), followed by those aged 70–79 years (30%). Overall, approx. 90% of patients were aged 60 years or older (Table 1).

The age distribution of HF patients reflects a marked increase in morbidity after age 60, reaching 431 per 100,000, with a continued rise in each successive age group (Table 1). The average age at HF diagnosis was 71.8 years, while the mean age across all HF patients was 75.2 years. Although the proportion of HF-related deaths within total mortality gradually decreased, the absolute number of such deaths increased from 2014 to 2021 – most notably in 2020–2021 – mirroring the overall rise in population mortality (Table 2).

Heart failure hospitalizations

During the analyzed years, the HFH rate in 2019 reached 1,022 per 100,000 individuals (primary or additional diagnosis), including 726 per 100,000 for HFH listed as the primary diagnosis. Across 2014–2021, HFH with a primary diagnosis ranged from 197,000 to 278,000, declining to 211,000 and 205,000 in 2020 and 2021, respectively (Figure 2E,F). There were significant increasing trends in HFH per 100,000 population from 2014 to 2019 for both HF as a primary diagnosis and HF as an overall diagnosis (Figure 2D, Figure 2E, respectively). Each year, HF-related hospitalizations exceeded the number of patients receiving treatment services (167,000–223,000) by 18–25%, resulting in an average of 1.18 to 1.25 hospitalizations per patient with at least one HFH in a given calendar year.

From 2014 to 2019, there was a 21% increase in HF patients experiencing ≥1 urgent HFH, rising from 36,300 to 44,000. Over the same period, the number of patients with ≥2 HFH within 12 months increased from 33,200–45,100 in 2014 to 38,700–54,700 in 2019. In 2020–2021, HFH numbers declined (24,700–38,400), most likely due to restricted access to the healthcare system during the COVID-19 pandemic. In terms of overall HF prevalence, individuals with ≥2 HFH represented 20% of all patients, totaling 181,100 of 918,800 in 2021.

Hospital treatment

From 2014 to 2019, hospital treatment for HF as the main diagnosis increased by 34%, reaching 223,000 cases; however, in 2020–2021 it declined by 22–24% to 168,000–173,000. Health services for HF, whether recorded as the primary or a concomitant diagnosis, followed similar patterns. Between 2014 and 2019, visits for HF as the main diagnosis rose by 41% to 298,000, then decreased by 24–27% to 226,000–219,000 in 2020–2021. In 2021, the average number of visits per patient with at least one HFH was 1.30, and 1.44 for patients with HF overall. Heart failure hospitalizations exceeded 250,000 annually until 2018, amounting to more than 1.6 million admissions between 2012 and 2018. This pattern corresponded with a significant upward trend in both the number of patients and the volume of HF-related services throughout the analyzed period (Figure 2F, Figure 3A).

Notably, 82% of these hospitalizations were emergency admissions, underscoring HF progression or limitations in OSC. Moreover, 60% of admissions occurred in internal medicine departments, whereas only 30% took place in cardiology departments. Only 1 in 12 hospitalizations (8.3%) involved patients younger than 60 years. Hospitalizations peaked in 2019, with 278,000 admissions for HF and more than 392,000 for overall HF diagnoses. Thereafter, the number of hospitalizations declined significantly, reaching 281,000 in 2021.

Healthcare pathway of patients with HF

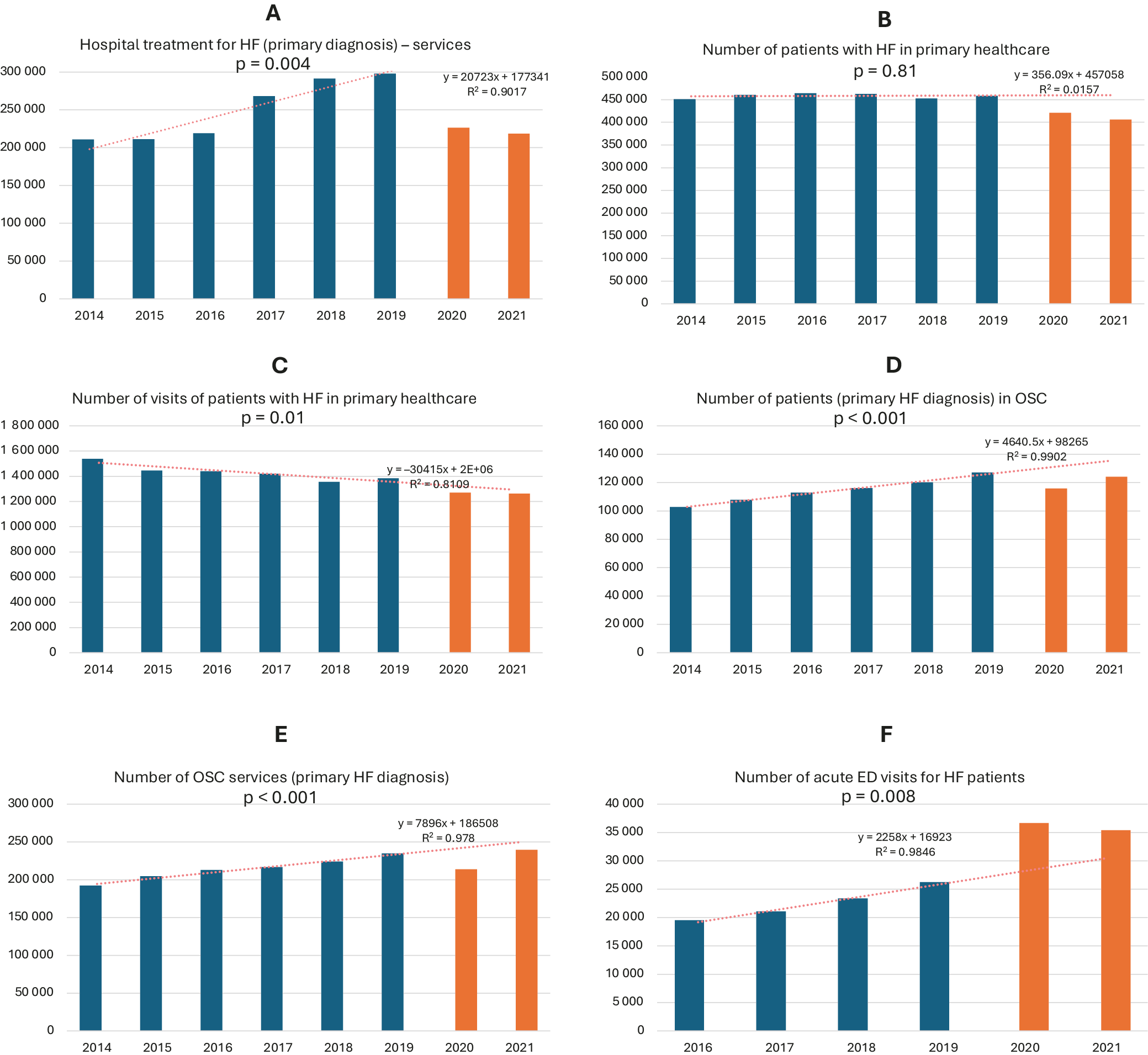

From 2014 to 2021, a total of 9.2 million healthcare services were recorded, most of which occurred in PHC (48%), followed by hospital treatments (22%) and nursing/care services (15%). Services provided in OSC amounted to nearly half the volume of those delivered in hospital settings. The healthcare pathway was analyzed for 1,062,157 HF patients, including those treated exclusively within a single healthcare service (n = 446,224), those receiving repeated care within the same service (n = 289,067), and those managed across multiple services (n = 615,933). Overall, the median number of healthcare services per HF patient was 4.

From 2014 to 2021, the proportion of initial HF diagnoses made in PHC declined from 44% to 29%, while hospital-based diagnoses increased. This shift occurred despite a relatively stable proportion of patients receiving PHC services, and was accompanied by a significant downward trend in HF-related PHC visits. Outpatient specialist care accounted for only 12–15% of HF diagnoses, and other healthcare services for approx. 4%. Following an HFH, patients most commonly return either to the hospital (39%) or to PHC (34%). After hospitalization or OSC visits, PHC accounts for the largest share of subsequent encounters – 50.3% and 24.5%, respectively. These findings underscore the central role of PHC in the management of HF in Poland, where PHC physicians oversee the majority of patient care, constituting 62% of all visits (n = 1,459,619).

Primary healthcare

Between 2014 and 2021, both the number of patients diagnosed with HF and the volume of HF-related services provided in PHC declined, for both primary and overall HF diagnoses (Figure 3B,C). Despite this, the number of medical centers providing HF services increased from 7,400 in 2014 to 7,700 in 2021 (Table 3).

The mean annual number of PHC visits per patient diagnosed with HF remained stable at 3 between 2014 and 2021. From 2014 to 2019, PHC physicians diagnosed an average of 458,000 HF patients annually, with a peak of 464,000 in 2016. However, in 2020–2021, this number declined by 10%, to an average of 413,000 patients. The total number of HF-related health services also decreased from 1.54 million in 2014 to 1.26 million in 2021, representing an 18% reduction.

Outpatient specialist care

The OSC health services for patients with HF increased steadily from 192,000 in 2014 to 235,000 in 2019, representing an average annual rise of approx. 8,600 visits and a significant upward trend over the observed period (Figure 3D,E). The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a reduction of HF-related visits in 2020 (by approx. 21,000), decreasing to 214,000 visits. Notably, in 2021 – despite ongoing pandemic conditions – healthcare services increased to 239,700, surpassing the 2019 peak (Figure 3D,E). Furthermore, our data show that the number of patients utilizing OSC across all medical specialties exceeded the number of those with HF as the main diagnosis by more than 30% when considering all patients diagnosed with HF. Additionally, when comparing the volume of healthcare services provided, the difference was approx. 40%. These findings suggest that HF patients treated in OSC settings have clinically significant comorbidities and a more complex clinical profile.

Emergency department

Analysis of Ministry of Health data from 2016 to 2021 on emergency department (ED) visits by HF patients revealed a recent upward trend. In the last 2 years, acute ED visits among HF patients exceeded 35,000 annually, compared with 19,500–26,300 in 2016–2019. This trend was further supported by an increase in the proportion of ED visits resulting in HFH, which rose to 61–63% in 2020–2021, in contrast to 29–38% during 2016–2019. This was reflected in a significant upward trend in HF-related medical services provided in the ED (Figure 3F). Notably, the percentage of ED visits resulting in death remained stable throughout 2014–2021 (2–3%).

Discussion

The study cohort, covering the years from 2014 to 2021, accurately reflects the diverse demographic and geographic characteristics of the Polish population with HF. It includes patients across a wide range of ages, socioeconomic backgrounds, and regions, ensuring comprehensive national representation. Based on data from the Ministry of Health and the Health Needs Map, the study offers essential insights into the evolving healthcare landscape in Poland over this 7-year period.

Epidemiology of HF in Poland

In Poland, nearly 150,000 HF-related deaths occur annually, corresponding to a population of more than 1 million individuals living with HF.2 This elevated mortality is driven by the substantial number of newly diagnosed HF cases and the poor prognosis observed in older adults, particularly those aged 75 years and above. Another Polish study reported that only 57% of individuals diagnosed with HF survived beyond 5 years.3 Furthermore, among individuals aged 75 years and older, the average survival period was approx. 4 years.6, 7

Previous HF studies reported an age-standardized prevalence of 1,130 per 100,000 population in Poland, the 5th highest among EU countries.8 In this study, even after standardization for age, sex, and place of residence, the prevalence was more than twice as high. Epidemiological projections suggest that HF incidence may continue to rise in the coming years, particularly between 2022 and 2031.9 Based on available data, the number of new HF cases is projected to rise from 120,200–207,300 in 2022 to 133,500–229,800 in 2031, representing an approx. 11% increase across projected scenarios.9 Consequently, a further increase in the total number of patients with HF cannot be excluded in the coming years, largely driven by demographic trends. According to Statistics Poland, the largest age groups affected by HF in Poland are currently individuals aged 60–69 years and 30–49 years.10

Finally, cardiovascular death – a predominant cause of mortality in Poland, accounting for 35% of all deaths in 2021, particularly among individuals aged 65 and older – now occurs at an estimated annual rate of approx. 175,000–180,000.9, 10

HF hospitalizations

Poland has consistently ranked among OECD countries with the highest number of HF hospitalizations, reporting 616 HFH per 100,000 citizens in 2019 – nearly 3 times the 34-country average of 220.4 Despite global reductions, Poland’s HFH rate has continued to rise since 2009. Our data show an increase in ED contacts during 2020–2021 accompanied by a decline in hospital treatments, likely reflecting reduced ward admissions – a negative prognostic factor with implications for healthcare financing in Poland.4

Zaleska-Kociecka et al. reported similar findings on HFH.11 The authors showed that patients with newly diagnosed HF had >1.5-fold higher risk of death with 2 hospitalizations (HR = 1.55), doubling with 3 hospitalizations (HR = 2.16), and nearly tripling with 4 hospitalizations (HR = 2.79).12 The average hospital stay was 7.5 days, trending upwards with 25% readmitted after index HFH (median follow-up: 1,072 days).12 Similar to our findings, the 30-day admission rate for a first HF rehospitalization was initially low (2.96%) but increased over time with subsequent hospitalizations.12

Healthcare pathway

An intensive strategy involving rapid medication adjustments and close monitoring post-HFH gained patient acceptance.13 It effectively alleviated symptoms, improved quality of life, and reduced the risk of 180-day all-cause mortality or HF readmission compared to standard care.13 Patients with ≥2 urgent HFH predominantly receive hospital or PHC services, with a minority referred to an OSC. This stands in contrast with European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, indicating an inefficient post-hospitalization HF treatment pathway.1 Notably, patients with prior HFH utilize a broader range of healthcare services over a shorter timeframe than those without HF history, emphasizing the predominant reliance on hospitals and primary care in their care provision.

Primary healthcare

In Poland, from 2014 to 2021, we observed a relatively consistent mean annual number of visits per HF patient through PHC system (n = 3). Notably, recent data for 2021 indicates a nearly 1/3 reduction in visits for HF as the main diagnosis compared to 2014.5 Concurrently, the number of services provided declined by 20% relative to 2014 data (health services provided for n = 439,000 patients). This suggests that less than half of HF-diagnosed patients engage with their PHC provider. Caution is warranted in interpreting these data due to potential limitations arising from the ICD-10 reporting system, allowing only 1 code per service and potentially constraining the comprehensive understanding in cases with multiple diagnoses.5

Outpatient specialist care

Our data demonstrate a systematic increase in OSC services for patients with HF as the primary diagnosis over the study period. Intriguingly, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase was observed – likely attributable to the incorporation of teleconsultations alongside traditional service formats, which helped compensate for the service deficit of previous years.14 Patients with HF as a comorbidity are notably more inclined to seek OSC care, indicating a complex clinical profile with additional comorbidities. Despite the prevalence of comorbidities, medical services for HF patients within the OSC system remain a minority, reflecting inadequate care, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, correlating with a rising hospitalization rate.14

Emergency department

The surge in urgent ED visits, particularly in the later years of the analysis, is noteworthy. This increase was likely driven by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and reduced access to PHC, OSC, and follow-up care. Notably, in contrast to other findings,14, 15 the increase in ED visits did not correspond to a higher mortality rate compared to the previous years in the analysis.

Improvements and disadvantages in the healthcare system

In the last 2 years in Poland, significant progress has been made in accessing innovative therapies.16 This includes increased availability of fundamental treatments like SGLT-2 inhibitors, reimbursed and provided free for those aged ≥65 years, addressing HF with reduced ejection fraction, chronic kidney disease, and type 2 diabetes.

Between 2015 and 2020, Poland maintained a stable number of OSC clinics. Despite the high HF prevalence, these patients receive less than 5% of all medical advice within OSC. Moreover, 90% of patients from cardiology departments and 60% from internal medicine departments were referred to OSC after hospitalization.17 Non-adherence to ESC guidelines, with over 50% missing follow-up within 3 months, highlights the need for a dedicated HF program to improve drug adherence.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Despite the absence of a dedicated HF nursing specialty in Poland, the Heart Failure Association of the Polish Cardiac Society has developed a curriculum for nurses, serving as an educational framework for HF care.19 As a result, there are currently approx. 1,500 certified HF nurses in the country. Numerous studies have shown that the implementation of structured HF programs significantly reduces the risk of rehospitalization and mortality.20, 21, 22, 23

Access to left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapy for advanced HF is another positive development in Poland. The Ministry of Health’s endorsement aligns with the recommendation of the Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System (No. 17/2022, issued June 2, 2022), which supports public reimbursement for the care of patients with advanced HF. The National Cardiology Network, operational in 7 Polish voivodeships, accelerates patient diagnosis and ensures OSC within 30 days. Establishing a comprehensive, coordinated care model for HF patients, coupled with medical community education, aims to address these issues and enhance outcomes.

Limitations of the study

This publication has several limitations. The observed decline in new HF cases and overall morbidity in 2020–2021 may be attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected healthcare access and diagnostic activity.24 We acknowledge that reporting disease occurrence in Poland using ICD-10 codes may be subject to error, as coding is linked to reimbursement procedures within the National Health Fund. Nevertheless, we believe that presenting these data offers a meaningful overview of progress – or its absence – across successive years in the occurrence of the diseases discussed, as demonstrated in this report. The data presented in the current article are derived from the Ministry of Health and are aggregated for HF described by ICD-10 coding I50 or J81. Therefore, we do not have the ability to provide the prevalence of each of those codes separately. Some new patients might not be registered in the payer’s billing system (ICD-10 codes I50 and J81). However, these unregistered patients are at high risk of HFH and in-hospital death,25 similar to the findings in this article. Finally, the analyzed data did not include exact dates of death, only information on whether the patient is alive or deceased; therefore, plotting Kaplan–Meier curves was not possible.

Conclusions

We have delineated the contemporary status of HF in Poland over the period 2014–2021. This extensive dataset provides a comprehensive overview of health patterns, healthcare utilization, and disparities in healthcare access and outcomes across the country.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15401298. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. Number of new HF patients in individual calendar years divided by the urgency of admission.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Expenses for HF-related healthcare services.

Data Availability Statement

Data come from the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Poland and cannot be made available to third parties.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Use of AI and AI-assisted technology

AI or AI-assisted technology was not used.