Abstract

Background. Despite legal advances and the depathologization of transgender identities, transgender individuals still face significant barriers and discrimination within healthcare systems. A pervasive lack of training in gender diversity among healthcare professionals often results in uncomfortable, even hostile, clinical encounters, exacerbating physical and mental health vulnerabilities. Consequently, fear of stigma and discrimination leads many transgender people to avoid seeking care, placing their wellbeing at further risk due to delayed or foregone medical attention.

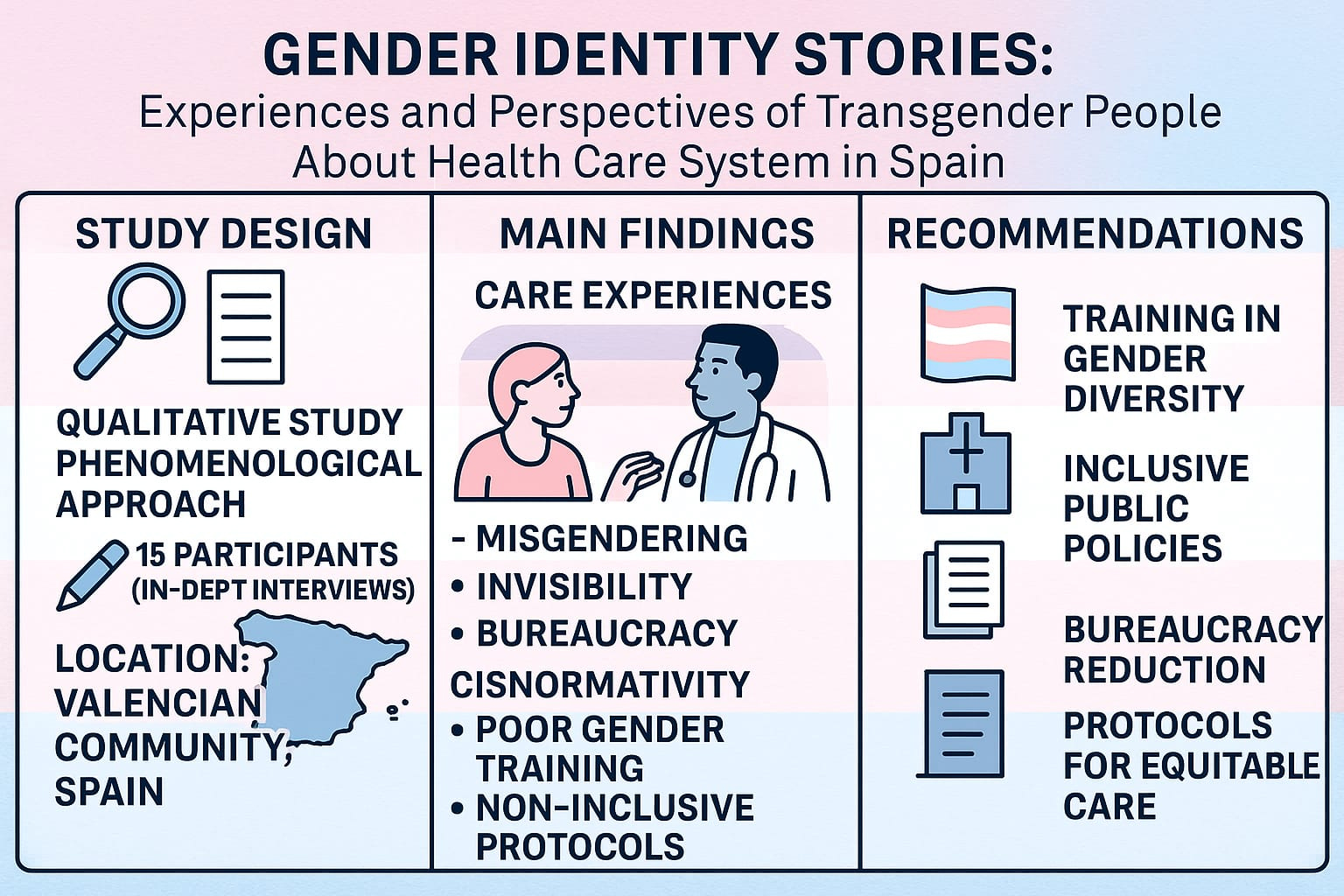

Objectives. To explore transgender individuals’ perceptions of healthcare professionals’ awareness and responsiveness to their care and support needs in the Valencian Community (Spain).

Materials and methods. We conducted a descriptive qualitative study with a phenomenological approach in the Valencian Community. Using convenience sampling, we recruited 14 participants. Data were collected between April and June 2022 via in-depth, semi-structured, open-ended interviews. The study comprised 2 sequential phases: An initial focus group session, followed by individual interviews conducted using a snowball sampling technique.

Results. We identified 3 thematic domains: T1: Experiences of professional care among transgender individuals; T2: Impact of cisgender-centric regulations within the healthcare system; T3: Gender diversity education needs for healthcare professionals.

Conclusions. The transformation of the health system is urgent to ensure inclusive and equitable care for transgender people. According to the interviews, they consider that better training of professionals will improve their care. In addition, they highlight the need to reduce bureaucratic barriers, create specific protocols, and improve access to specialized treatment. Implementing inclusive public policies will contribute to a fairer and more accessible system.

Key words: qualitative research, social determinants of health, transgender, health disparities, gender diversity

Background

Despite regulatory advances and the depathologization of transgender identities, transgender people continue to face barriers and gaps in access to adequate healthcare.1, 2 Although the World Health Organization (WHO) eliminated “gender dysphoria” as a mental disorder in its International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) in 2019, the reality of healthcare shows that transphobic practices and widespread ignorance on the part of healthcare personnel persist.3 The lack of training in sexual and gender diversity issues in health sciences careers translates into poor and sometimes disrespectful care towards this population.4

Stigma remains a fundamental barrier in the healthcare environment, where the perception of transgender people as “different” or “problematic” influences the treatment offered. According to reports from organizations such as Lambda and FELGTB (Federación Estatal de Lesbianas, Gays, Transexuales y Bisexuales), many transgender people are questioned about their identity or transition process during medical consultations, which generates an invasive and dehumanizing experience.5 In some cases, healthcare professionals refer to patients by their name assigned at birth (or “deadname”), completely ignoring their gender identity and generating an environment of vulnerability and mistreatment.6, 7 These deficiencies profoundly impact the healthcare system.8, 9 The lack of trained professionals to address the specific needs of transgender people, such as psychological accompaniment, hormone support, or care during the transition period, leads to insufficient and poorly informed care.10, 11 From a healthcare approach perspective, addressing the needs of transgender individuals requires not only clinical competence but also an institutional commitment to equity.10 This involves the integration of inclusive care models that ensure continuity, accessibility, and person-centered services. An affirmative healthcare model recognizes gender diversity, avoids pathologization and fosters safe spaces where people can receive holistic care, including physical, emotional and social wellbeing, without fear of discrimination.11 This situation affects both the quality of healthcare and the confidence of transgender patients in the healthcare system, who often prefer to avoid medical consultations so as not to expose themselves to situations of discrimination or discomfort.12 Low adherence to medical treatment becomes therefore a serious risk, as fear of mistreatment or misunderstanding leads to many health problems remaining undiagnosed or untreated.13

Given this reality, it would be a priority to design inclusive healthcare protocols and promote the training of healthcare professionals from a trans-inclusive perspective.2, 13 Transgender people need to be cared for in a respectful and safe environment that recognizes their diversity without questioning or pathologizing them.14 For healthcare professionals, comprehensive training is essential to improve specific clinical knowledge and to foster attitudes that ensure dignified and empathetic treatment of sexual and gender diversity, including the proper use of inclusive language. It should also provide a basic understanding of the legislation regulating aspects of transgender health, such as Law 4/2023 of February 28, aimed at ensuring the accurate and effective equality of transgender people and safeguarding the rights of LGTBI+ individuals.15 These actions are essential to build a fairer and more respectful healthcare system capable of adequately serving everyone, regardless of gender identity.16

The impact of these shortcomings goes beyond the physical. Discrimination and stigma in health services generate a situation of vulnerability that has serious repercussions on the mental health of transgender people.17 Several studies have shown that constant exposure to transphobia in healthcare settings is related to an increased risk of developing disorders such as anxiety, depression and increased rates of suicide and self-harm.18, 19 This reality is linked to the phenomenon known as “minority stress”, which refers to the psychological impact experienced by transgender people as a result of social exclusion, discrimination, and lack of support. In addition, fear of rejection, mistreatment, or misinformation from health professionals leads many transgender people to avoid seeking healthcare. This often results in delayed visits and postponed treatment. This avoidance, motivated by previous experiences of discrimination or the perception that professionals are not prepared to care for them adequately, prevents early detection of diseases, access to crucial treatments5 and, in some cases, the recourse of these patients to unsafe centers or resources. In the long term, this reluctance to seek medical care results in a general deterioration of the person’s health. It also increases the risk of untreated chronic diseases, complications such as infections, and severe mental health problems.20, 21

At the structural level, there are also barriers to access to specialized services and resources.22 Despite attempts by some autonomous communities to implement trans-inclusive protocols, many of these initiatives are insufficient or limited in scope. Transgender people sometimes have to travel long distances to access gender identity units or specialized services, which aggravates the precariousness of their care. Decentralization in the design and implementation of public health policies generates inequalities in the coverage and quality of services, depending on the territory where they reside. It is urgent to design inclusive healthcare protocols and promote the training of health professionals from a trans-inclusive perspective.23 Transgender people need to be cared for in a respectful and safe environment that recognizes their identities without questioning or pathologizing them.24 For healthcare professionals, comprehensive training is required, encompassing both specific medical knowledge and sensitization to ensure the dignified and empathetic treatment of sexual and gender diversity.25 These actions are essential to build a fairer and more respectful healthcare system capable of adequately caring for all people, regardless of gender identity.

Objectives

To explore the perceptions of transgender people on the awareness of healthcare personnel concerning their care and accompaniment in the Valencian Community, Spain.

Materials and methods

Study design

A descriptive qualitative study with a phenomenological approach was conducted to explore and understand individual human experience within its specific context.26 This study was based on the theory of relativism, which holds that all perspectives are personal and valid, and has been used previously in studies such as Eckstrand et al.27 Under this approach, it is recognized that people with LGTBI+ identities have diverse experiences, not a single reality.28 This study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Communicating Qualitative Studies (COREQ)29 and the Standards for Communicating Qualitative Research (Supplementary File 1).

Experience or role of researchers

The research team consisted of 5 women and 6 men, including 4 nurses with qualitative research design experience (E.G.C.-B, A.T-R, P.D.P-H, and M.A.-B) and 2 researchers with clinical and mental health research experience (P.D.P-H and J.C.-R). The data were triangulated by 2 external researchers (G.M.-N and R.J.-V). None of the research team members had any previous relationship with the participants. At the start of the study, the position of the researchers was determined based on their beliefs, previous experiences, theoretical framework, and motivation for the study.

Participants and setting

We employed purposive convenience sampling, recruiting volunteer members of the Transgender group from Lambda in the Valencian Community. Data saturation was achieved by the 14th participant, after which no new information emerged, rendering further coding unnecessary.30 Initially, a focus group was conducted with 10 participants. Subsequently, individual interviews were conducted using the snowball method until data saturation was reached. The researchers did not consider it necessary to recruit more participants. Table 1 presents the demographic data of the participants.

Data collection instrument

The data were collected in 2 complementary phases from April to June 2022. First, a focus group was held at the headquarters of Lambda Valencia, facilitated by 2 researchers (M.A.-B and N.C.-R). The session, which lasted 90 min, allowed for a collective exploration of the participants’ experiences and perceptions of the study phenomenon. We developed a focus group (FG) discussion guide, informed by existing literature, to address specific topics of interest (Table 2). Given the subject’s sensitivity, participants were informed that they could interrupt their participation anytime if they experienced emotional discomfort. In the 2nd phase, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted, following the same guide of questions used in the focus group. The interviews were conducted face-to-face, individually, in a comfortable environment for the participants, with an average duration of 49 min. Their flexible nature allowed the interviewees to express themselves freely while the researchers inquired about emerging aspects. Notes were taken during both phases to record contextual observations, interactions and methodological reflections. The transcripts of the focus groups and interviews generated 158,760 written words, providing a substantial volume of data for analysis. The transcripts were returned to the participants for additional comments. Finally, all data were securely stored in a digital location with restricted access, ensuring the confidentiality of the information collected (Table 2).

Data analysis

An iterative and inductive thematic analysis approach was carried out based on the methodology described by Braun and Clarke.31 This process allowed data analysis from focus groups, in-depth interviews and field notes, ensuring the triangulation of information to strengthen the study’s validity. First, 2 researchers (M.A.-B and N.C.-R) familiarized themselves with the data by repeatedly listening to the audio and independently reading the focus group transcripts and interviews. In parallel, they reviewed the field notes taken during data collection, which provided additional information about the participants’ context, interactions and behaviors. During this initial phase, they made handwritten annotations to identify connections, key phrases and emerging patterns in the participants’ discourses, enriching the understanding of the phenomenon studied. They then proceeded to highlight and classify statements that directly addressed the research question, ensuring that the selection of fragments was comprehensive and representative of the various perspectives collected. Statements that directly addressed the research question were then highlighted and categorized, ensuring that the selection of excerpts was comprehensive and representative of the multiple perspectives collected. These fragments were coded using short phrases or keywords to synthesize their core meaning. For this purpose, the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS-ti.32 was used, facilitating the information’s organization and structuring.

In the following analysis stage, the codes generated were grouped into preliminary categories, from which the first themes began to emerge. This process was carried out collaboratively, with the participation of 3 researchers (E.G.C.-B, A.T-R and P.D.P-H). The data triangulation between interviews, focus groups and field notes made it possible to identify convergences and divergences in the narratives, providing a more robust and profound vision of the phenomenon being analyzed. To ensure the coherence and validity of the analysis, any discrepancies in the interpretation of the data were discussed within the team until a consensus was reached. This reflective and dynamic process allowed the initial themes to be reorganized and redefined according to the connections and nuances identified in the data. Finally, a comprehensive review of the identified themes was conducted to verify their relevance and consistency with the research question. Combining multiple data sources and methodological triangulation contributed to an enriched interpretation, ensuring a more complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon studied.

A qualitative analysis of each interview and the researchers’ field notes was conducted using an inductive thematic approach. Codes were generated to identify the most descriptive content, which was then reduced and grouped to identify common categories representing meaningful content units. This process led to the emergence of thematic areas describing the experiences of study participants.

Three researchers (E.G.C.-B, A.T-R and P.D.P-H) conducted independent double coding of each interview and each field note. They then met to discuss, compare and refine their findings. Subsequently, the same process was carried out with the themes. In addition, joint meetings were held to consolidate the results of the analysis, as well as an external audit with an independent researcher to ensure confirmability. All coding were discussed by the research team until a consensus was reached on the main categories and themes, creating a final matrix of categories.

To control the rigor and reliability of the qualitative data, the criteria of Guba and Lincoln 30 were applied (Table 3).

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia (approval No. UV-INV_ETICA-2662329; verification code S126XGMF60UWV255). All participants were briefed on the study’s objectives and signed written informed consent before participating in interviews and focus groups, with assurance of their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Data collection was anonymous, voluntary and confidential; sessions were audio-recorded with participants’ permission and transcribed verbatim, and no personal identifiers were documented. The information obtained was treated anonymously and confidentially, complying with the General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and Organic Law 3/2018. The investigators did not declare ethical, moral or legal conflicts, nor did they receive financial compensation, just as the participants did not receive compensation for their collaboration in the study.

Results

Of the 14 focus group participants, 8 (57%) identified as transgender women and 6 (42%) as transgender men. The mean age was 34.6 years (standard deviation (SD) = 12.84).

Three thematic blocks with their categories were identified: (T1) Experience of professional care for transgender people; (T2) Impact of cisgender regulations in the Health System; and (T3) Need for education in gender diversity for health professionals (Table 4).

Theme 1. Experiences of healthcare professionals in caring for transgender people

Quality of treatment received

Healthcare and perceptions of gender identity are critical to the wellbeing of transgender people, but unfortunately, the experience is not always the same for everyone. While some people find adequate and respectful treatment, others face significant obstacles in their interaction with the healthcare system, often due to prejudice or lack of training on gender issues: I have generally had a good experience in my process because I have gone to the same health center every time, and they have attended to me well, both the one who attends to me on the phone and the family doctor who makes me feel comfortable (FG_P3). This type of experience shows the importance of longitudinal care that ensures constant and personalized treatment by the same professionals, allowing patients to feel comfortable and safe, ensuring more fluid access to the medical care they need. However, some face serious difficulties, and seeking support in these services points to poor or even discriminatory treatment: One girl I know who went to the Gender Unit encountered a nurse who did not respect her gender identity and did not treat her well at all (FG_P1). Others emphasize how specialized gender services do not meet the expectations of empathy. They even report situations in which healthcare personnel do not respect the gender identity of transgender people: I have to say that, curiously, I find better treatment outside the Gender Unit than inside. In fact, I have had awful experiences (FG_P2). Lack of sensitivity may also be reflected in erroneous or derogatory diagnoses: I had to change my family doctor. When I went to tell him what was wrong with me and that I wanted to have surgery, his conclusion was that I wanted to remove my boobs because they were too big, and since they were not big enough to have surgery, he was not going to send me to any specialist and that I should go home (FG_P5).

Bureaucracy, waiting lists, and a lack of resources are persistent barriers within the healthcare system. In contrast, some patients have relatively quick access to the care they need. The reality remains a constant struggle for many others to overcome these obstacles, highlighting the urgent need to reform the system to ensure that all patients, regardless of their situation, receive the care they require without having to wait unnecessarily.

Professional skills and training

The experiences shared by transgender people regarding healthcare reflect a notable disparity in the sensitivity and preparation of the staff. On the one hand, some professionals show an attitude of skepticism toward the gender identity of their patients: With my family doctor, she kind of denies me, she doubts me all the time asking me if I am really sure (FG_P6). In contrast, other more empathetic professionals have respected the patient’s name and pronouns, showing active support by referring them to safe spaces. For some people, the lack of respect for their identity is perceived as a conscious choice by the professional: I don’t think it’s complicated either: ‘My name is X, call me X, call me X.’ The person knows what you are telling them and when they don’t respect it, they know what you are telling them. The person knows what you are saying, and when they don’t respect it on purpose, it is because they don’t feel like it (FG_P2). This lack of understanding can cause transgender people to feel out of place in medical settings: The truth is that you feel a bit alien (FG_P10).

Lack of knowledge about the transgender reality and lack of training in gender diversity are significant barriers in healthcare: Because they have no idea how it affects. It is noticeable that they lack knowledge about the transgender reality, and the gender issue is not deepened in their studies (FG_P7). Some patients have had to assume the role of educators, instructing the professionals about their needs and experiences: It is noticeable that they lack knowledge about the transgender reality, the professionals ask many questions, to try to inform the patient directly (I2). This type of comment not only denotes a clear ignorance of the needs and experiences of transgender people. It is observed that, although some healthcare professionals do not have specialized training in issues related to transgender people, such as the correct use of inclusive language, what makes the difference is their willingness to learn and adapt to the specific needs of these patients. Unfortunately, stereotypes and misunderstandings persist among healthcare personnel, as reflected in this comment: I’ve heard it more than once: ‘Look, not a man, not a woman.’ But the truth is, that’s not how it is... I know I’m not what they say (I4). This type of prejudice perpetuates an unsafe environment for transgender patients.

Access to specialized treatment

Access to healthcare for transgender people continues to be a problem that affects many people: With the endocrinology part, I have had very poor treatment because you need them to be there, and they are not (FG_P2). In addition, many people must share the same doctor due to the lack of professionals: It is that practically all of us have the same doctor (FG_P1). This situation directly impacts the quality of care and delays necessary treatments. Waiting times can be disproportionately long, affecting the quality of life of those seeking treatment: The first time I got an appointment, I had to wait 9 months… By the time I started hormone therapy, I was starting university and had to go through all my changes there (I1). These ideas reflect the slowness of the process, which can generate distress and frustration in patients. In turn, the lack of access to the public system means that those with economic resources can access the same doctors through private consultations, which raises an ethical question: Deep down, they’re all the same... What really matters is getting money, and that’s not ethical (I2).

Hormone treatment, in addition to being a lifelong process for many people, involves side effects and important decisions: They told me I wouldn’t become infertile until 5 or 10 years later and that I could start hormone therapy and then freeze my eggs... The thing is, everyone said something different (FG_P8). The side effects of treatment can generate emotional instability and notable physical changes: Each one affects us differently, but of course it affects us psychologically (I3).

In some cases, they delay the start of their treatment to preserve their fertility: Even though they asked me the typical question about whether I want to have kids, and at 20 or 21, I honestly had no idea. That really messed me up, to be honest. Since I was so unsure about what to do, I ended up freezing my eggs to use them when the time comes (FG_ P8). Surgical procedures are also a key point in the transition process, with experiences varying regarding results and recovery: There are many surgeries because at minimum one operation to construct the penis, another to place the testicular implants, and another surgery so you can have an erection. After all that, if you manage to have some sensitivity (FG_P5). However, these procedures may involve prolonged pain and discomfort. Voice therapy is also fundamental for many people in their transition process: There’s something about my voice that doesn’t feel right – I’m not sure if it should be stronger or softer. I’m working on it… That’s why I’m in voice therapy (I2). The importance of voice in gender identity highlights the need for equal access to this type of therapy.

Many people describe the transition process as an emotional […] roller coaster: You always feel a mix of emotions; as a child, I used to cry because I couldn’t be who I wanted to be (FG_P1). However, the support of the environment can make a big difference. While some people have had a favorable environment, others have experienced social rejection and loss of relationships: There are people who are with you at first, but then disappear... In the end, the ones that matter remain (I2). Despite the challenges, the shared experiences also reflect the importance of self-determination and personal struggle: You know something’s wrong, but until you name it, you don’t understand it. And when you recognize yourself and fight for yourself, it feels amazing (I3).

Theme 2. Impact of cisgender regulations in the health system

Prevailing cisnormative regulations within the healthcare system impose significant barriers on transgender individuals, compelling them to conform to restrictive gender-expression standards to access treatment and services. These requirements not only perpetuate discrimination but also undermine both the right to health and the affirmation of one’s gender identity.

Expectations of gender expression

One of the main problems faced by transgender people within the healthcare system is the need to conform to a stereotypical image of the gender with which they identify to receive care: Here, to get something, you have to show that you are a woman; you have to wear long hair, dresses and heels; otherwise, it is very difficult to be referred (FG_P2). This statement underscores the implicit expectation that individuals conform to conventional standards of femininity in order to attain social recognition. Other participants reinforce this idea by advising other transgender women about the importance of appearing normative gender to be accepted in medical consultations: I tell all the transgender girls I know to lie on the test and wear the best dress. If you have heels, wear them, if you have makeup, wear it. Until there’s a change, that’s the way it’s going to be (FG_P1). This statement highlights that, beyond gender identity, validation within the healthcare system depends on the ability to fit into a pre-designed image of femininity or masculinity. Such circumstances place an added burden on transgender individuals, compelling them to alter their appearance and behavior to access essential medical care.

The impact of cisgender normativity also extends to the legal recognition of gender identity, affecting access to adequate medical services: The trans person still hasn’t changed their gender on their ID (FG_P3). Without documents that correspond to their identity, many transgender people face constant questioning about their gender, which makes healthcare complex. In other cases, despite having updated documents, they face bureaucratic obstacles and resistance from staff.

Lack of inclusive spaces

The existence of significant barriers for people who do not conform to gender binarism is evident, especially in areas where segregation by sex continues to be the norm. This lack of recognition and adaptation to the diversity of identities generates situations of exclusion and discomfort, directly affecting the wellbeing and dignity of the people concerned. One of the main problems pointed out is the invisibilization of non-binary people in environments structured under a strict binary scheme: If it is already difficult to be accepted when you do not fit into the traditional categories of man and woman, imagine what it means for a non-binary person: They simply stop taking you into account (FG_P4).

Distributing spaces in institutions such as hospitals or nursing homes poses an additional difficulty. Allocating rooms solely on the basis of legal or biological sex creates uncomfortable situations and does not respect the identity of many people: I don’t think it’s appropriate for rooms to be divided into male and female only. But, if that is how it should be, they should at least allow each person to be in the one that corresponds to their identity (FG_P5). The absence of inclusive bathrooms represents another essential barrier. The obligation to choose between a male or female restroom can be an unpleasant or even stigmatizing experience for many transgender people. In this sense, one solution suggested by the interviewees would be the implementation of shared bathrooms accessible to all: The ideal would be to have a common bathroom (FG_P4). Another problem identified is the constant need to explain and justify one’s identity in institutional settings. The lack of clear protocols in many institutions is highlighted, which generates improvisation and resistance on the part of the staff. This situation not only creates uncertainty but also perpetuates discrimination.

Obsolete diagnoses and pathologization

Across many settings, particularly in healthcare, transgender and gender-diverse individuals often encounter arbitrary treatment by providers, resulting in inequitable and distressing experiences: Something that also makes me very angry is that, in any field, whether this is health or administrative or whatever, in the end, you are exposed to the arbitrariness of the person who touches you (FG_P1). Medical decisions, diagnoses and treatments can depend more on the beliefs or prejudices of the professional on duty than on a criterion that is really based on the patient’s welfare. A clear example of this point is the persistence of obsolete diagnoses in clinical records, which is not only a technical problem but has real consequences for the care and treatment received: In my medical records from October of last year, they still put ‘Dual-role transvestism’ as my diagnosis (FG_P5). This term, in addition to being outdated, reinforces a pathologizing view of transgender and non-binary identities by classifying gender experiences as disorders instead of recognizing them as part of human diversity. Pathologization is especially evident when a transgender individual’s gender identity is referenced in clinical contexts where it is irrelevant: If you go to the emergency because you’ve dislocated a shoulder, you’re going to get: ‘Transsexualism’ (FG_P1). This phenomenon illustrates that the lack of updating of healthcare personnel can make transgender identity ubiquitous data, even when it has no relation to the reason for consultation.

Conversely, requiring a formal diagnosis to access certain specialized health services underscores the enduring medicalized, biologicist approach: That is true, and at least you have to have a diagnosis before you can be sent to a specialist. In the Unit, we use the current manual, the ICD-11, I think (I4). Although ICD-11 has advanced by removing pathologizing terms such as “transsexualism” and replacing them with “gender incongruence”, in practice, barriers still exist: Ugh, it’s all pretty rough, I mean, there are a lot of things that just aren’t right... (FG_P4) This comment suggests that, despite theoretical improvements in the approach to transgender health, in practice, there are still gaps, inconsistencies, and resistance on the part of healthcare personnel.

Theme 3. Gender diversity education needs for health professionals

Formal diversity training

Education on gender diversity is an essential component of healthcare professional training. Healthcare should focus not only on clinical factors but also on empathy and proper treatment of patients, ensuring an inclusive and respectful approach: Periodic training to health personnel, both on purely medical issues and on issues of empathy and treatment of patients (FG_P1). Regular training activities must be aimed at healthcare personnel, strictly covering clinical knowledge, communication, and inclusive treatment skills. Including these topics in the curricula and continuing education would improve care for people with diverse gender identities. For example, in Argentina, in some medical universities, “treatment of transgender people” has already been incorporated into the curriculum, which represents a significant advance in the training of future health professionals: My daughter, who is in her 4th year of medical school in Argentina, told me that just this year they have a part of the subject that is ‘Treatment of transgender people’ (FG_P3). This initiative highlights the importance of integrating content on gender diversity in formal education. Any profession should have basic training in sexual, gender and family diversity, but especially the medical field should have an exclusive subject on that (FG_P5).

In this sense, all health-related professions require basic training in sexual, gender, and family diversity. In healthcare, this training should be mandatory, integrated across all curricula, and include dedicated modules that comprehensively address gender diversity issues.

And there are many things out there that we still have to cope with, within society, health professionals, at the legal level... (I2). Despite progress, there are still many challenges within society and the healthcare professional community regarding inclusive care and understanding of gender diversity. Ongoing training and the implementation of diversity education policies would significantly reduce discrimination and enhance healthcare quality.

Empathy and respect in the consultation

Treatment in the healthcare environment is a fundamental element in guaranteeing dignified and quality care. Empathetic, respectful medical consultations improve patient experience and foster trust in the healthcare system. However, the testimonies collected show that practices that generate discomfort still persist, which underlines the need to improve staff training in terms of diversity and sensitization. One of the most relevant aspects pointed out is the importance of asking the person’s name and pronouns in a natural way, without assuming information based on official documents or appearance. Asking for this not only avoids uncomfortable situations but also represents an essential gesture of respect and recognition of each patient’s identity. Simply ask for the name, regardless of the name you may have on the registry. Ask for the name and pronouns as a matter of course (FG_P1).

On the other hand, experiences are mentioned in which healthcare personnel ask unnecessary or invasive questions, such as the previous registry name, anatomy, or surgical procedures that a person may or may not have undergone. Such questions are often irrelevant to the clinical encounter and can be intrusive, leaving patients feeling exposed or vulnerable: Don’t ask me what my name was, don’t ask me what I have between my legs, don’t ask me if I am going to have surgery, it’s none of your business (FG_P9). In this sense, it is emphasized that the focus should be kept on the real reason for the consultation, without diverting the conversation to personal aspects unrelated to the health problem for which the person comes to the medical center.

Similarly, reports indicate that the inherent dynamics of healthcare settings can cause patient discomfort. For example, in gynecological consultations, a person may feel part of the environment until their name is called out loud. At this point, they experience looks of judgment or surprise from other people present: Like when you go to the gynecologist, and you are surrounded by women and, while you are sitting down, you may be accompanying a woman, but the moment they call your name, and you stand up, everyone looks at you (I4). These experiences highlight the need to rethink specific procedures so everyone feels comfortable and safe in these spaces. Finally, although some healthcare professionals show sensitivity and care in their treatment, they sometimes make mistakes or overlook specific fundamental details to ensure respectful care. Insufficient training and awareness of these issues lead to inconsistent patient experiences – some consultations proceed smoothly, while others induce significant stress or anxiety. This anxiety is expressed in experiences about the process of psychological accompaniment in the context of gender transition, which seems to be marked by a mixture of support and pressure, together with institutional bureaucracy. The importance of good information and psychological follow-up is emphasized. However, it is mentioned that this follow-up should not be interpreted as an external validation of a person’s identity, but as ongoing support. This perspective reflects a critique of the validation approach, suggesting that accompaniment should be a tool for wellbeing, not a barrier to personal identity. They reflect how the process of psychological support for transgender people is an experience that varies greatly depending on the professionals involved and the institutional structures: Having that psychological support makes me feel much calmer, and for the first time in my life, I can open up and share what I’ve been through with someone (I2).

Strategies for normalization

The testimonies collected reflect a consensus on the importance of education as a central axis for normalization. The need to implement courses in companies and healthcare centers to generate knowledge and promote structural changes in society is highlighted: Regarding education, which we all consider crucial to establish knowledge and standardization, I think we could take advantage of it and give courses in companies and medical centers (FG_P7).

Despite progress in some regions, such as the Valencian Community, forms of discrimination persist, underscoring the urgency of strengthening education as a key tool for social change. The Valencian Community is doing well, but there is still discrimination, and we cannot relax; we have to tighten up, and the only way out is education (FG_P3). In this sense, it is pointed out that the educational system, including the training of medical personnel, continues to reproduce a normative vision that perceives what is different as not acceptable. The educational system, including education to future medical personnel, maintains a style of society that understands that anything different outside of normativity is dangerous (FG_P4).

The lack of a unified registry that allows documenting and addressing existing problems in a structured manner was identified, which evidences the need for a shared database to improve the institutional response: Sure, but it should be registered. So a complaint is that there should be a common database (I1). Finally, the lack of adequate knowledge in certain areas is highlighted, reinforcing that education is a fundamental factor in advancing standardization. The truth is, there are terms they’ve never even heard of they just don’t understand them (I1).

These results reflect the complexity of understanding the experiences of transgender people. Figure 1 allows us to establish the following themes: (T1) Experience of professional care for transgender people; (T2) Impact of cisgender regulations in the healthcare system; (T3) Gender diversity education needs for healthcare professionals. The program ATLAS-ti was used to code and synthesize the data, and a graphic designer prepared the results in the form of a map of agents and interactions, as shown in Figure 1.32

Discussion

At the beginning of the study, we set out to learn about the experiences of transgender people in their relationship with the healthcare system. Access to adequate and respectful healthcare is a fundamental right, especially for transgender people, who often face significant barriers within the healthcare system.33 These barriers can manifest in healthcare personnel’s lack of knowledge about this population’s specific needs, explicit or implicit discrimination in health services, and the scarcity of adequate clinical protocols for their care.

The results of this study show contrasting experiences in the healthcare of transgender people, reflecting both advances in awareness and persistent deficiencies in the quality of treatment received. While some professionals have demonstrated greater openness and willingness to provide respectful care, attitudes and practices persist that generate mistrust and discomfort in transgender patients. This, in turn, may discourage their timely access to medical care. Healthcare providers must cultivate a safe, supportive and empathetic environment grounded in clinical expertise, ensuring that transgender individuals receive care free from prejudice and unnecessary barriers. Incorporating gender identity content throughout all stages of healthcare training, including continuing nursing education, is essential for delivering truly inclusive, high-quality care.25 Such training equips healthcare professionals with the competencies to provide comprehensive, respectful care that addresses the unique needs of transgender individuals.34

One key finding is the wide variability in care quality: While some transgender individuals describe encounters with empathetic, eager-to-learn professionals, others recount experiences of discrimination, disrespect and a lack of awareness regarding their specific needs.35 This finding could be attributed to the influence of stereotype threat in the healthcare setting, 36 as well as the fear that, in the medical office, harmful stereotypes about transgender people are reinforced. Additionally, there is concern that an individual’s social group identity may influence how healthcare professionals perceive, evaluate and treat them.35 This idea suggests the need to strengthen the training of healthcare personnel in gender diversity and to implement institutional strategies to ensure equitable, human rights-based care.37 Health systems should establish periodic training for professionals to be updated on best practices in inclusive care and to prevent the perpetuation of stereotypes and prejudices in healthcare.38

Another relevant aspect is the impact of bureaucracy and scarcity of resources on the quality of care. A lack of sufficient public resources was identified; transgender people face long waiting lists and difficulties in accessing transgender health specialists. This point reinforces the need to increase investment in specialized health services and ensure timely access without discrimination. In addition, access to hormone treatments and gender-affirming surgeries is often hindered by overly restrictive criteria, prolonging the distress of those seeking professional assistance.39 Allocating additional resources to mental health programs for the transgender community, and supporting research to develop adaptable, evidence-based interventions, is essential for expanding our understanding of clinical efficacy, improving mental health outcomes, and ensuring the long-term sustainability of these initiatives.40

Providing culturally competent and gender-affirmative care is a relevant aspect for various disciplines. However, evidence points to insufficient preparation and limited knowledge about the specific needs and challenges of transgender individuals.37 The findings show that healthcare professionals who seek to inform themselves and adapt their practice to the needs of transgender patients generate more positive and satisfying experiences. This finding is consistent with literature highlighting the importance of gender diversity training as an essential tool to improve the relationship between patients and healthcare professionals.41, 42 Student-led initiatives have effectively enhanced peers’ knowledge and confidence in providing transgender-affirming healthcare.43 Encouraging the development of tools tailored to the transgender community that address their unique needs and support an interdisciplinary treatment approach is essential.44 Additionally, establishing support networks and safe spaces for transgender individuals can foster more comprehensive, patient-centered care. Implementing these enhancements would not only benefit transgender individuals, but also strengthen the healthcare system’s ability to equitably and respectfully address the diverse needs of all users. In the long term, establishing specialized, multidisciplinary units – staffed by experts in endocrinology, mental health, surgery, and social support – could profoundly advance transgender people’s right to health.

Limitations

This study offers valuable insights into the healthcare experiences of transgender individuals in Spain, underscoring the challenges they face and the urgent need for more inclusive clinical protocols. Training healthcare personnel in gender diversity, removing bureaucratic barriers, and creating safe spaces are key strategies to improve their access to healthcare. In addition, the expansion of specialized resources and cooperation with organizations working to defend their rights is essential.

Despite these advances, the study has limitations, such as the small sample size and the need for further research to generalize the findings. In addition, the results may not be generalizable to other parts of the world due to cultural complexities. Participants may not have disclosed very sensitive information. Implementing change requires political will, adequate resources, and overcoming resistance from some healthcare sectors. Continued advocacy for public policies that ensure equitable and respectful healthcare for all individuals is essential, guaranteeing that gender identity does not impede access to quality services.

Furthermore, one important limitation noted by the reviewers is the lack of analysis regarding differences in discourse between trans men and trans women. That is, the study does not include a gender perspective within the trans population itself. It is possible that the needs of both groups differ and that they face distinct challenges, which future research should address to ensure more inclusive and nuanced approaches.

Conclusions

The conclusions of this study highlight the urgent need to transform the healthcare system to guarantee inclusive and equitable care for transgender people. The people interviewed expressed the need for this transformation to feel better cared for and accompanied throughout their entire process. Awareness raising and training of healthcare personnel, the design of specific protocols, and the reduction of bureaucratic barriers are essential to achieve a fairer health system. It is also crucial to improve accessibility to specialized treatment and create safe spaces that respect each person’s gender identity. Equally important is training professionals in the care of transgender people, strengthening their knowledge of specific health needs, and facilitating better access to resources. In addition, the development and implementation of inclusive public policies are key to ensuring that healthcare is a guaranteed right, thus promoting wellbeing and equity in access to health.

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research, the supporting data are not available.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16570654. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary File 1. COREQ checklist.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.

.jpg)