Abstract

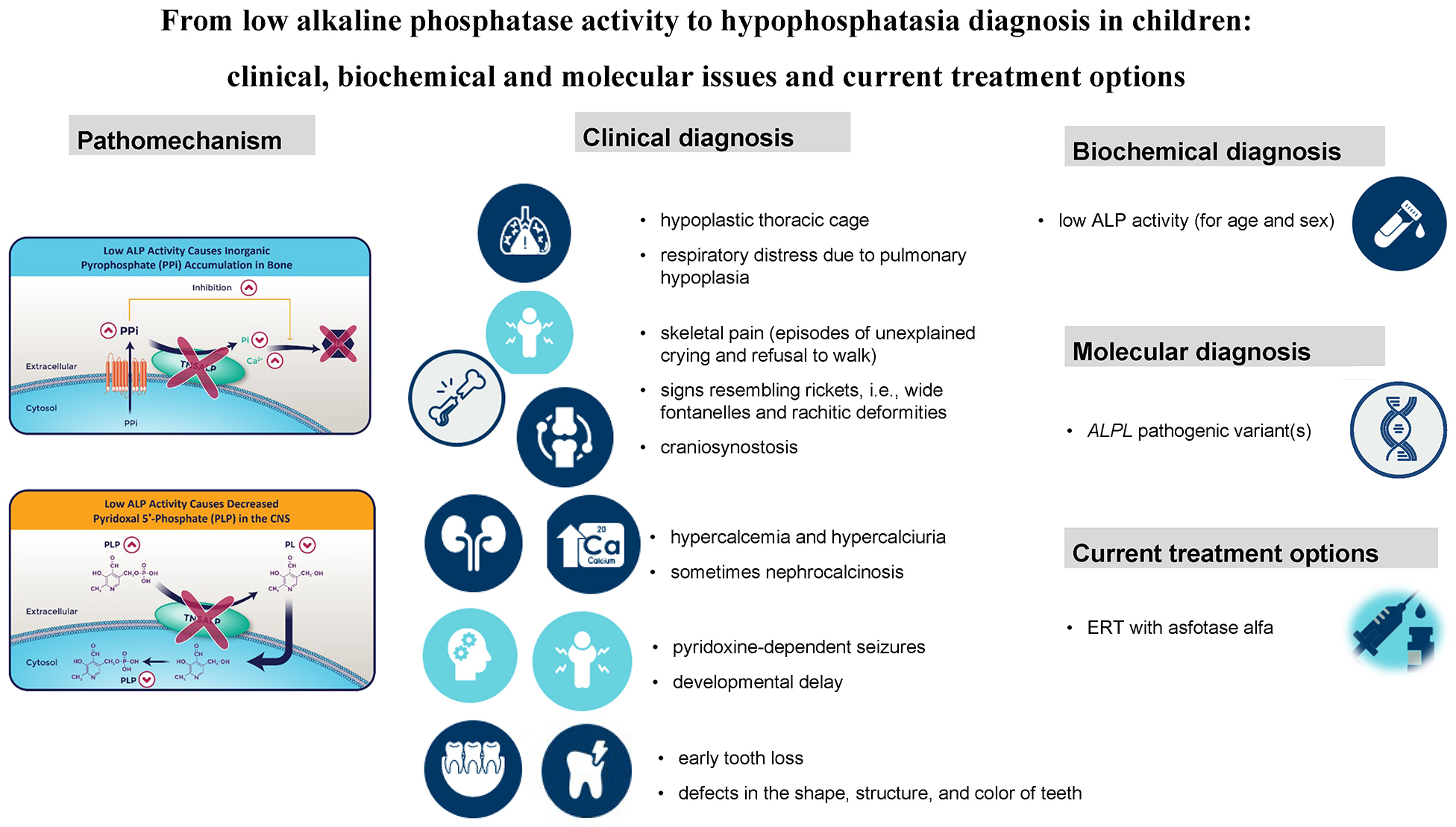

Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is an inherited metabolic disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in the ALPL gene encoding a tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP). It has been classified based on age at first disease manifestation, including lethal perinatal, benign perinatal, infantile, juvenile, adult, and odontohypophosphatasia. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assay and genetic testing. The main diagnostic clue is the low (for age and sex) ALP activity. In any patient with suspected HPP or skeletal/bone deformities/dysplasia, it is recommended to evaluate phospho-calcium metabolism, which is useful in differential diagnosis. Genetic diagnosis of HPP requires identification of a disease-causing variant(s) (pathogenic). In Europe, the most frequent ALPL variants are c.571G>A, c.407G>A and c.1250A>G, while the most frequently detected variants in the world are c.1250A>G, c.571G>A and c.1133A>T. Asfotase alfa, a recombinant human TNSALP enzyme replacement therapy, is now available for the treatment of HPP. The article provides an up-to-date overview of clinical, biochemical and molecular features of HPP. Treatment strategy in HPP was also described.

Key words: hypophosphatasia, ALPL gene, low ALP activity, asfotase alfa

Introduction

Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is an inherited metabolic disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the ALPL gene encoding a tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 TNSALP is predominantly active in the bone, liver, kidney, and teeth, being responsible for inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP) and phosphoethanolamine (PEA) dephosphorylation. The enzymatic deficiency of TNSALP reflects the pathomechanism of HPP, including mostly the mineralization defect but also the deficiency of the biologically active form of vitamin B6 in the central nervous system. A low serum ALP activity (hypophosphatasemia) is indicative of TNSALP deficiency, and thus constitutes the biochemical hallmark of HPP.1, 2, 3, 4, 5

The exact incidence of HPP is not known; however, the severe form is estimated to occur in approx. 1 per 300,000 births in Europe. Among Mennonites in Manitoba, Canada, the birth prevalence of the infantile form of HPP is estimated to be about 1 in 2,500, owing to a founder effect.1, 2, 3, 4

Hypophosphatasia is classified according to the age at first clinical manifestation into 6 forms: lethal perinatal, benign perinatal, infantile, juvenile, adult, and odontohypophosphatasia (odontoHPP).1, 2, 3 The last form presents solely with dental manifestations. Diagnosis is established based on clinical presentation, biochemical findings (low serum ALP activity) and genetic (molecular) testing. Hypophosphatasia follows either an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, associated with homozygous or compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in the ALPL gene, or an autosomal dominant pattern involving a single heterozygous pathogenic ALPL variant.3, 4, 6

Objectives

This study aimed to review the current literature on the clinical, biochemical and molecular features of HPP in children. In addition, current therapeutic approaches for pediatric HPP are summarized.7, 8, 9

Clinical and biochemical features

Severe lethal HPP is characterized by an absent ossification of bones. Other radiographic and sonographic features of perinatal HPP include the following: shortening, bowing and angulation of the long bones; osteochondral spurs; small, beaded ribs; deficient or absent bone ossification; increased nuchal translucency; and polyhydramnios.10

The association of pyridoxine-dependent seizures with perinatal HPP as a result of deficient TNSALP activity in the cerebral cortex was first described in 1967.11 TNSALP dephosphorylates PLP to pyridoxal, which can cross the blood–brain barrier, where it is rephosphorylated and serves as a cofactor for glutamic acid decarboxylase.1, 2, 3, 9 Benign perinatal form of HPP with a gradual improvement of bone disease after birth is also reported (Table 1).

Infantile HPP presents before 6 months of age with failure to thrive, developmental delay and signs resembling rickets, such as rachitic deformities (Table 1).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 12 For neonates and infants with HPP suspicion, a complete series of long bones radiographs, including the skull, axial and appendicular skeleton, are recommended.

Infantile HPP carries a mortality rate of approx. 50%, which increases further in the presence of pyridoxine-dependent seizures.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 12 In those who survive infancy, premature loss of teeth, persistent rickets and craniosynostosis are commonly observed.13 The blocked entry of minerals into the skeleton could lead to hypercalcemia and/or hypercalciuria (and sometimes nephrocalcinosis). This phenomenon is less commonly observed in the childhood form of HPP.

In patients with childhood (juvenile) HPP, symptoms appear after the first 6 months of age and before 18 years of age. This type could be further subdivided into mild and severe (Table 1). Childhood HPP is characterized by a premature tooth loss; bone hypomineralization (rickets-like changes); short stature; bone fragility, as well as bone and muscular pain (episodes of unexplained crying and refusal to walk).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 14 The key radiographic features include “tongues” of lucency projecting from the growth plates into the metaphyses; wide, irregular physes and fractures, involving mainly the long bones; and osteopenia.12

Apart from impaired bone mineralization, growth failure and premature loss of decidual teeth, the infantile and childhood forms of HPP could be associated with craniosynostosis.13

Odontohypophosphatasia is a mild form of HPP characterized solely by dental manifestations in the absence of skeletal abnormalities (Table 1).

In the last year, the International HPP Working Group, comprised of a multidisciplinary team of HPP experts, published diagnostic criteria for HPP (Table 2).15 In December 2024, the South American recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients were also published. Based on this document, it is recommended to suspect HPP in children presenting with short stature, deformities of the long bones, craniosynostosis, delayed motor development, gait disturbances, hypotonia, musculoskeletal pain, and premature loss of deciduous teeth (before the age of 6 years).16

The main diagnostic clue is a low serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity for age and sex.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 12, 15, 16, 17 At least 2 different ALP activity measurements are recommended in patients with suspected HPP. A low ALP level requires the exclusion of other conditions or drugs which can contribute to reduction of its activity (Table 3).17 Measurement of ALP substrates, such as urinary PEA and inorganic PPi, as well as serum PLP, may also be considered; however, these assays are not routinely available.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17

Molecular features

The ALPL gene (HGNC ID: 438, OMIM *171760) is located on chromosome 1p36.12 It is composed of 12 exons (2536 nucleotides; MANE select: NM_000478.6), while 11 of them are coding. Translation length is 524 residues (NP_000469.3). Alternative splicing results in 7 transcript variants, at least 1 of which encodes a preproprotein that is proteolytically processed to generate the mature enzyme.

Genetic diagnosis of a HPP requires identification of a disease-causing variant(s) (pathogenic). The ALPL gene sequence analysis may lead to detection of single-nucleotide variants (SNV), including missense, nonsense and splice site variants, small insertion/deletion (indel), as well as larger ALPL deletions or duplications.18 Molecular genetic testing approaches may include single-gene or variant-targeted testing, as well as comprehensive genomic testing. The most commonly used method in the diagnostic process is single-gene sequencing, followed by targeted variant analysis and whole-exome sequencing (WES).19

To date, about 470 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (including missense, nonsense, splice site, frameshift, deletions, insertions, and large rearrangements) have been described in the ClinVar database (January 15, 2025) and in the Johannes Kepler University (JKU) ALPL Gene Variant Database.20 These variants are responsible for an extraordinary clinical heterogeneity of the disorder.

Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are distributed throughout the entire length of the gene. There are no regions within the coding sequence that can be defined as hotspots.21, 22 The highest proportion of pathogenic variants is localized to the homodimer interface, the crown domain and the active site of the protein.19

In most patients, disease-causing variants are located in the coding sequence, but pathogenic variants may also be localized in regulatory regions or introns. A few larger ALPL deletions and duplications have been reported (The ALPL Gene Variant Database, ClinVar). In Europe, the most frequent variants are c.571G>A, c.407G>A and c.1250A>G, while the most frequently detected variants in the world are c.1250A>G, c.571G>A and c.1133A>T.19

Identification of known pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants usually explains the molecular cause of the disease. However, evaluation of a novel variant, or variants of uncertain significance (VUS), is challenging due to the lack of scientific evidence on their pathogenicity. An international consortium of HPP experts prepared the ALPL gene variant database to help with interpretation and provide up-to-date information about genetic variations of the ALPL gene.

Differential diagnosis

Due to the fact that HPP is clinically very heterogeneous, it is recommended to evaluate phospho-calcium metabolism in every patient with suspected HPP or skeletal/bone deformities/dysplasia (Table 4).21

Neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism (NSHPT; # 239200)

should be evaluated in every neonate with very high parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels and severe life-threatening hypercalcemia (>20 mg/dL). The clinical manifestation resembles HPP and includes failure to thrive, hypotonia, skeletal demineralization, and respiratory distress. It is a very rare inherited disorder associated with inactivating mutations in the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) gene.23

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is the most common form of primary osteoporosis in children, according to the definition of pediatric osteoporosis by the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD).23 The main clinical features of OI include recurrent fractures, skeletal deformities, short stature, blue sclera, dentinogenesis imperfecta, hearing loss, and ligamentous laxity.24 However, comparing HPP and OI, both pathomechanisms and clinical presentations are quite different. It is also unclear whether the incidence of fractures in patients with HPP is as high as in OI.21 A perinatal HPP should be distinguished from OI or skeletal dysplasia by sequencing COL1A1, COL1A2, CRTAP, and LBR genes.25 Both OI and perinatal/infantile HPP share features of reduced bone density, deficient ossification of the skull vault, bowed long bones, fractures, gracile ribs, and narrow thorax.21

Genetic testing of infantile and childhood-onset HPP may include genes involved in the Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS) and other disorders with skeletal abnormalities. Genes such as COL1A1, COL2A2, DSPP, LIFR, NOTCH2, P4HB, SEC24D, SOX9, and RUNX2 should be taken into consideration.

Secondary (acquired) osteoporosis develops in children with chronic systemic illnesses due to the effects of the disease itself or its treatment.24 Defective skeletal mineralization is prevalent early in the course of pediatric chronic kidney disease (CKD), prior to the development of abnormalities in bone turnover. In 2006, the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes introduced the term ‘”chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder” (CKD-MBD) to describe this clinical entity.25 The definition of CKD-MKD includes the following: biochemical abnormalities (calcium, phosphate, PTH, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D), bone abnormalities (short stature, reduced mineralization and increased risk of fractures) and extra-skeletal calcification.26

Treatment strategy in HPP

Asfotase alfa is a bone-targeted, recombinant form of TNSALP, administered subcutaneously, that replaces deficient enzyme activity and reduces the extracellular accumulation of its substrates.27 Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with asfotase alfa (Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Boston, USA) was first approved in 2015 in Japan, followed by approvals in Canada, the EU and the USA.28 However, in some EU countries, such as Poland, ERT with asfotase alfa has recently become available (since October 1, 2024) as part of a drug program financed by the National Health Fund.

Enzyme replacement therapy with asfotase alfa is intended for patients with perinatal, infantile or childhood forms of HPP. Regarding the childhood-onset, ERT is indicated for children who did not reach the expected stages of motor development or suffer from musculoskeletal pain affecting the inability to perform daily activities, especially limited ability to walk independently.27, 28, 29

In infants and children with HPP, asfotase alfa improved skeletal mineralization assessed radiographically (evident from 3–6 months) and was accompanied by improvement in developmental milestones and pulmonary (respiratory) function (reflecting better mineralization of the rib cage).27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The comparison to historical controls showed a significantly prolonged overall survival in patients with perinatal or infantile HPP. In infants and children with HPP, catch-up growth, improvement and normalization of muscle strength and enhanced ability to perform activities of daily living have been observed.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32

Asfotase alfa has generally been well tolerated. Injection site reactions of mild-to-moderate severity have been commonly reported. Other, less commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events included lipodystrophy, nephrocalcinosis and ectopic calcifications. 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32

Limitations

This article has several limitations. It represents a narrative literature review conducted from a clinician’s perspective. The focus was on summarizing existing evidence and presenting key information relevant to everyday clinical practice. The section on treatment strategies in HPP highlights the efficacy and safety of asfotase alfa but does not encompass all available research data.

Conclusions

This literature review focused on HPP in children. Despite its heterogeneous clinical presentation, the index of suspicion is raised by low serum ALP activity for age and sex. Genetic testing, specifically ALPL gene sequencing, is recommended for all pediatric patients with clinical and biochemical suspicion of HPP. Enzyme replacement therapy with asfotase alfa represents an effective and well-tolerated treatment for children with HPP.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technology

Not applicable