Abstract

Background. The COVID-19 pandemic severely restricted global access to healthcare, including for patients with laryngeal cancer (LC).

Objectives. To compare laryngeal cancer stage distribution (TNM classification), surgical treatment patterns (types of surgery and perioperative complications), and timelines before vs 1 year after the COVID-19 pandemic declaration.

Materials and methods. We conducted a retrospective, single-center, cross-sectional study at a tertiary care center in Poland. The analysis included 110 patients hospitalized for laryngeal cancer during 2 six-month intervals: October 2019–March 2020 (prepandemic, group 1) and October 2021–March 2022 (post-pandemic, group 2).

Results. Group 1 included 49 patients, and group 2 included 61. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with males comprising 96.9% of group 1 and 83.6% of group 2. Admissions via the fast-track cancer pathway increased from 33.3% in group 1 to 52.5% in group 2. Although a higher proportion of patients in group 2 were classified as stage IVB by TNM, the difference was not statistically significant. Surgical treatment patterns were largely consistent across groups, except for a decrease in total laryngectomy from 18.4% in group 1 to 3.3% in group 2. Moderately differentiated tumors (G2) were more common in group 1 (66.7%) than in group 2 (35%). High concordance was observed between clinical and pathological staging for tumor size (79.1%) and regional lymph node metastasis (87.5%).

Conclusions. Future research should extend the post-COVID-19 observation period, as pandemic-related adverse effects on cancer diagnosis and outcomes may not fully manifest until several years later.

Key words: laryngeal cancer, head and neck cancer, TNM, COVID-19, pandemic

Background

Laryngeal cancer (LC) is the 2nd most common site of head and neck cancer (HNC), followed by oral cavity cancer,1 and the incidence of LC among all types of cancer is listed at the 17th position worldwide. Furthermore, mortality from LC worldwide is about 1.66 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants per year.2 Although the incidence rate of LC in Poland decreased from 7.7 to 6.03 between 2010 and 2018,3 LC remains a major problem. In men, it is in the 9th position of the most common cancer site and represents 2% of all primary cancer sites, and in women, it is in the 32nd position.3 Regrettably, LC mortality rates remain high. In 2021, the age standardised death rate was 1.35 (1.259–1.449) worldwide.4

One of the most important survival outcomes in patients with LC is the stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis.5 A recent meta-analysis of 32,128 patients found that advanced disease (stage III–IV) by the tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) classification confers a 2.46-fold higher risk of mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 2.46; 95% confidence interval 1.83–3.29; p < 0.001).5 The advanced stage necessitates more complex, often multimodal treatment and is linked to poorer survival than early-stage disease. The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly disrupted multiple aspects of healthcare system operations, restricting patient access to providers. COVID-19 has led to the rapid spread of the virus and then resulted in a global pandemic, announced by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020.6 The disruption and delays in cancer treatment associated with the pandemic could be attributed to several factors. These include reduced access to healthcare providers or diagnostic tests. Additionally, patients may fear sequelae from SARS-CoV-2 infection or misdiagnose LC as a COVID-19 infection, since symptoms could be similar at the beginning.7 The impact of pandemic-related delays on LC staging remains incompletely understood.

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether the COVID-19 pandemic disruptions had influenced the greater advancement of LC according to the TNM classification. We suspected that 1 year after the pandemic, the number of patients with a more advanced cancer stage was higher than before the pandemic. In addition, we conducted a comparative analysis of surgical types, complication rates, mortality incidence, and the proportion of second primary cancers, as well as the concordance between clinical TNM (cTNM) and pathological TNM (pTNM) assessments of LC before and after the pandemic.

Materials and methods

Study design and settings

This single-center, retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Otolaryngology and Oncologic Head and Neck Surgery at the 5th Military Hospital with Polyclinic in Kraków, Poland. Throughout the initial lockdown, surgical services remained active; guidelines prioritized operations for head and neck cancer (HNC) and other life-threatening conditions, while elective procedures for clinically stable patients were deferred. The study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Jagiellonian University Bioethical Committee (approval No. 1072.6120.329.2021).

Participants

Study data were extracted from electronic health records of patients hospitalized for LC before the COVID-19 pandemic (October 1, 2019–April 30, 2020; group 1) and 1 year after the pandemic onset (October 1, 2021–April 30, 2022; group 2). Patients aged over 18 years with newly diagnosed or recurrent LC were identified using ICD-10 code C32.8 Exclusion criteria included hypopharyngeal cancer with laryngeal involvement and admissions solely for CT or MRI evaluation (Supplementary Fig. 1)

Variables

We recorded demographic data, admission dates, referral sources, surgical procedures, complications, and histopathological findings. Tumor staging was performed according to the Union for International Cancer Control’s TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, 8th edition.9 Clinical TNM staging (cT for tumor extent and cN for regional lymph node involvement) was determined at admission using physical examination findings, imaging studies (CT, MRI, or both), and laryngeal endoscopy recordings reviewed in the IRIS endoscopy software, which enables recording and storage of laryngeal endoscopies performed during visits. Pathological assessment of tumor extent (pT) and regional lymph node metastasis (pN) was performed by a pathomorphologist based on histopathological examination. The incidence of mortality and the occurrence of subsequent primary cancer during the follow-up was evaluated on January 15, 2025.

Statistics analysis

Qualitative variables are presented as counts and percentages and compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when at least 20% of contingency table cells have an expected frequency below five. We used the Bonferroni method as a correction for multiple testing. Compliance with the normal distribution for continuous variables was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Since the distributions deviated from normality (age: Shapiro–Wilk test, group 1: W = 0.967, p = 0.033; group 2: W = 0.988, p = 0.423; hospitalization duration and surgery time: p < 0.001 for both groups), we used the Mann–Whitney U test. Continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges. For ordinal variables and for cancer grading and cancer staging between groups, the Fisher exact test was used. Agreement between clinical and pathological staging was assessed using Cohen’s weighted kappa, comparing cT vs pT and cN vs pN. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed for 2 intervals – time from 1st appointment to death and time from initial patient contact to hospital admission – and differences between curves were assessed using the Peto–Peto test. The level of significance was considered below 0.05, unless specified otherwise, when the Bonferroni correction was applied. Statistical analyses were conducted using PS IMAGO PRO v. 9.0 software (IBM SPSS v. 29.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) for all tests except Kaplan–Meier analyses, which utilized Statistica v. 13.3 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA).

Results

A total of 110 adult patients, 49 for group 1 and 61 for group 2, were included in the study. The proportions between men and women were 9:1. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of sex, age, duration of hospitalization, and percentage of cancer recurrence (Table 1). The majority of patients were from the Lesser Poland Voivodeship (73.5% and 82% in groups 1 and 2, respectively). Before the pandemic, the majority of patients (56.3%) were admitted via planned hospitalization, whereas in the postpandemic period, most (52.2%) entered through the fast-track cancer pathway (Table 1).

As Table 2 shows, there was a lower number of total laryngectomies in group 2 than in group 1 (2 (3.3%) vs 9 (18.4%), respectively, p = 0.009). The percentage of other types of surgery was similar in both groups. Of the patients undergoing total laryngectomy, 8 received it as primary treatment, and 3 underwent secondary therapy for recurrent disease – 1 after cordectomy, 1 after partial laryngectomy, and 1 following combined radiation therapy, cordectomy, and partial laryngectomy. Bilateral lymphadenectomy was performed in 7 patients in group 1 and 2 in group 2, while unilateral lymphadenectomy was conducted in 5 patients in group 1 and 10 in group 2.

Four patients in group 2 were disqualified from surgical treatment due to the progression of the disease and comorbidities (their TNM stages were T4bN2cM1, T4aN2cM1, T4bN3bMx, and T4aN2cMx). Four patients (2 from each group) declined treatment after LC was confirmed by biopsy, and 4 others withdrew consent during the biopsy procedure after hospital admission.

The median surgery duration was 30 min in both groups (group 1: interquartile range [IQR] 15–95 min; group 2: IQR 15–85 min). The difference was not statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U = 1419.0; p = 0.649). There was also no evidence that complications after surgery differed between the groups (Supplementary Table 1). One patient in each group died during hospitalization due to complications of LC.

Subgroup analysis

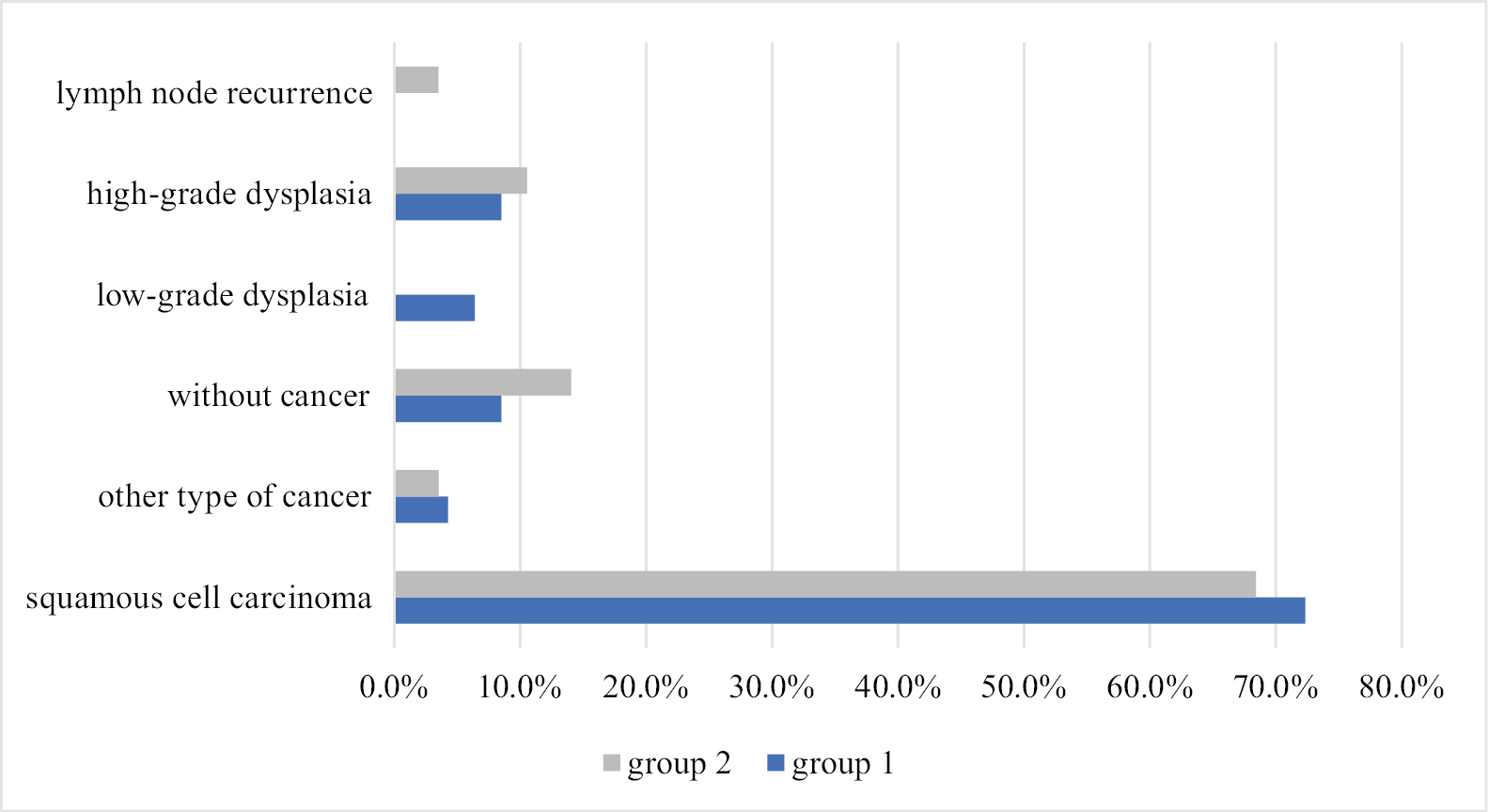

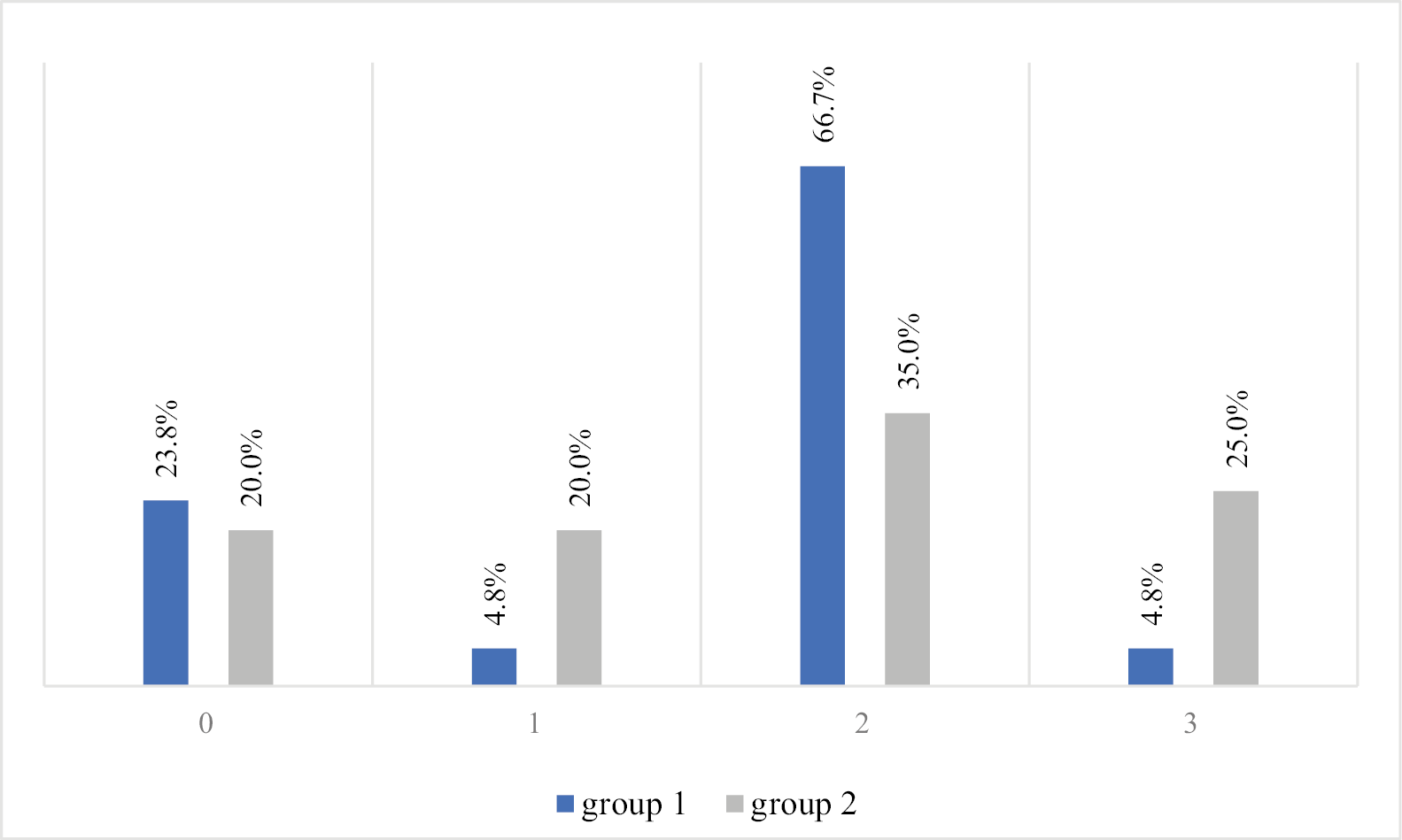

Further statistical analyses excluded patients who underwent only endoscopic laryngeal biopsy. Histopathological findings were similar across both groups (Figure 1), with squamous cell carcinoma the predominant cancer type (72.3% in group 1 and 68.4% in group 2). For 4 subjects in group 1 and 8 in group 2 with suspicion of cancer recurrence, the biopsy results were negative (Figure 1). Other histological subtypes observed included sarcomatoid carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma. In both groups, the majority of subjects had grade 2 cancer, which occurred in 66.7% and 35% of patients in groups 1 and 2, respectively (Figure 2).

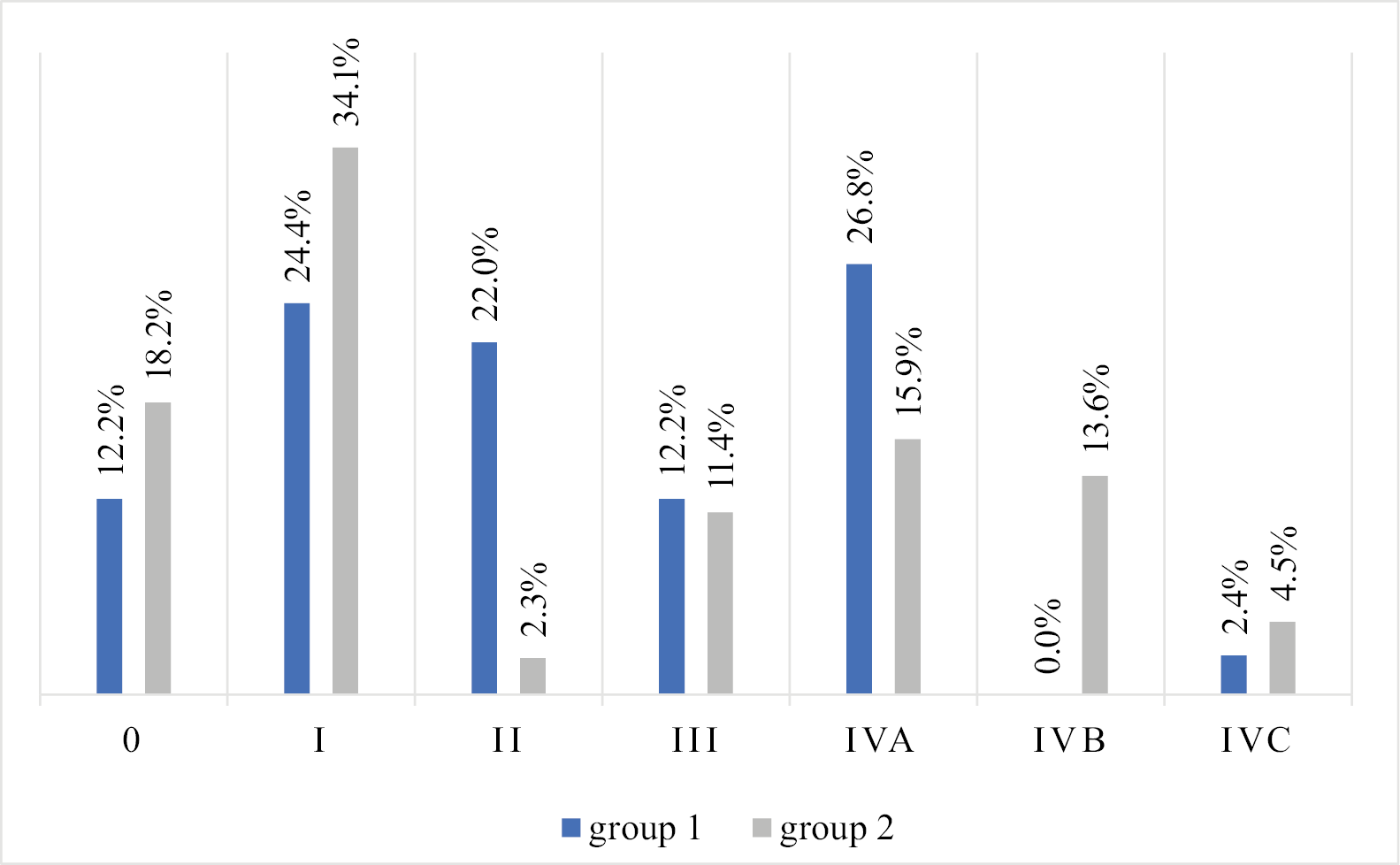

In terms of cancer stage, the analysis showed that in group 2 there was a higher percentage of patients in stage IVB and a lower percentage in stage II compared to group 1, but this difference was not statistically significant (the Fisher exact test p = 0.011, but p < 0.004 was set as significant according to the Bonferroni correction). In group 1, stage IVA was the most common (26.8%), with no cases of stage IVB. In group 2, stage I predominated (34.1%) (Figure 3).

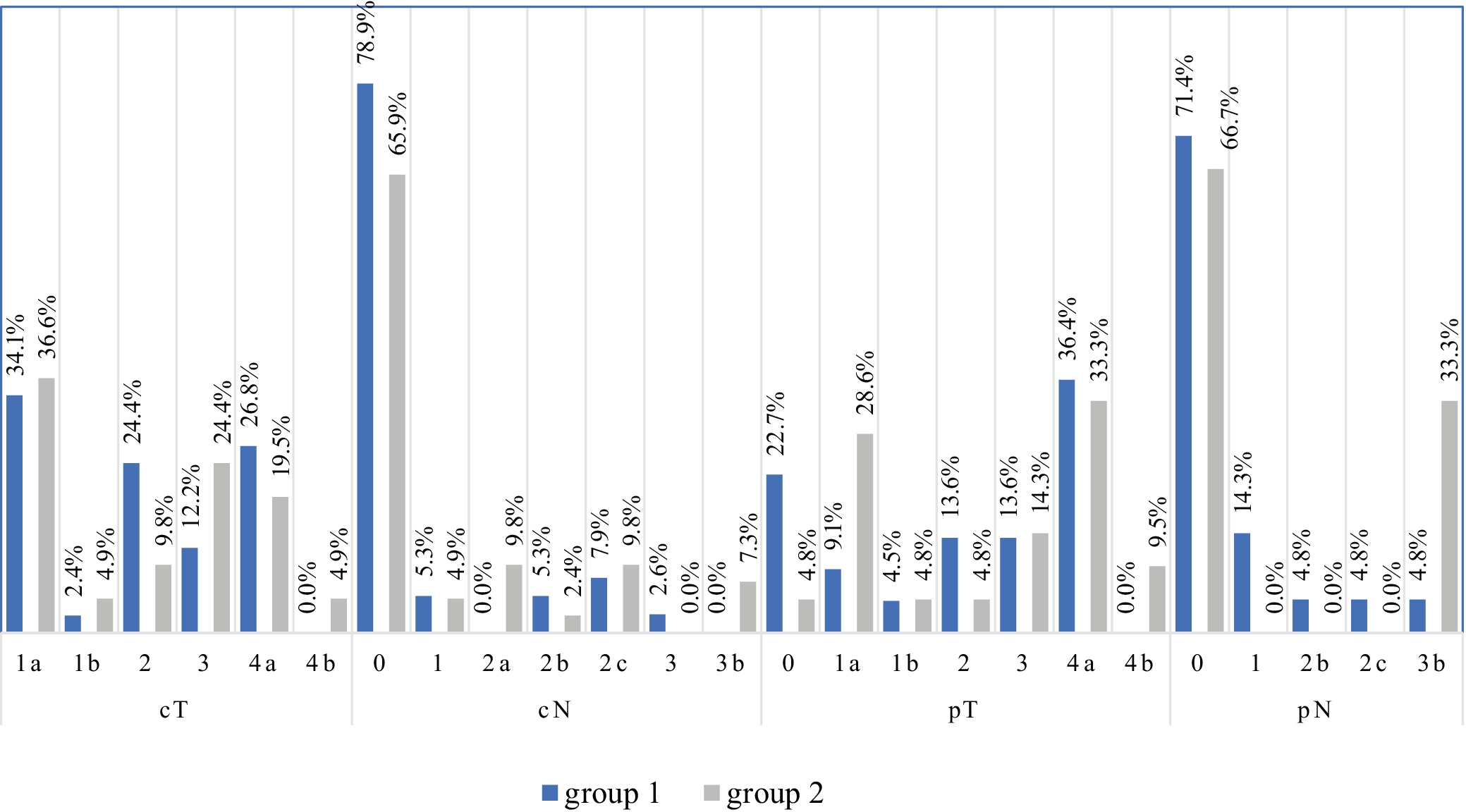

In the analysis of primary tumor alone in clinical evaluation (cT), the most common was stage T1a (34.1% and 36.6% in groups 1 and 2, respectively). Pathological evaluation excluded cancer in 22.7% of subjects in group 1 and 4.8% in group 2 and confirmed stage pT4a in 36.4% in group 1 and 33.3% in group 2 (Figure 4). The vast majority of patients have not had nodal metastases on cN and pN examinations.

Regarding the comparison of tumor size in cT and pT assessment, a high agreement of 79.1% was found (Cohen’s weighted kappa = 0.736, p < 0.001; Supplementary Table 2). Concordance between clinical (cN) and pathological (pN) regional lymph node assessments was 87.5% (Cohen’s weighted κ = 0.726; p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 3).

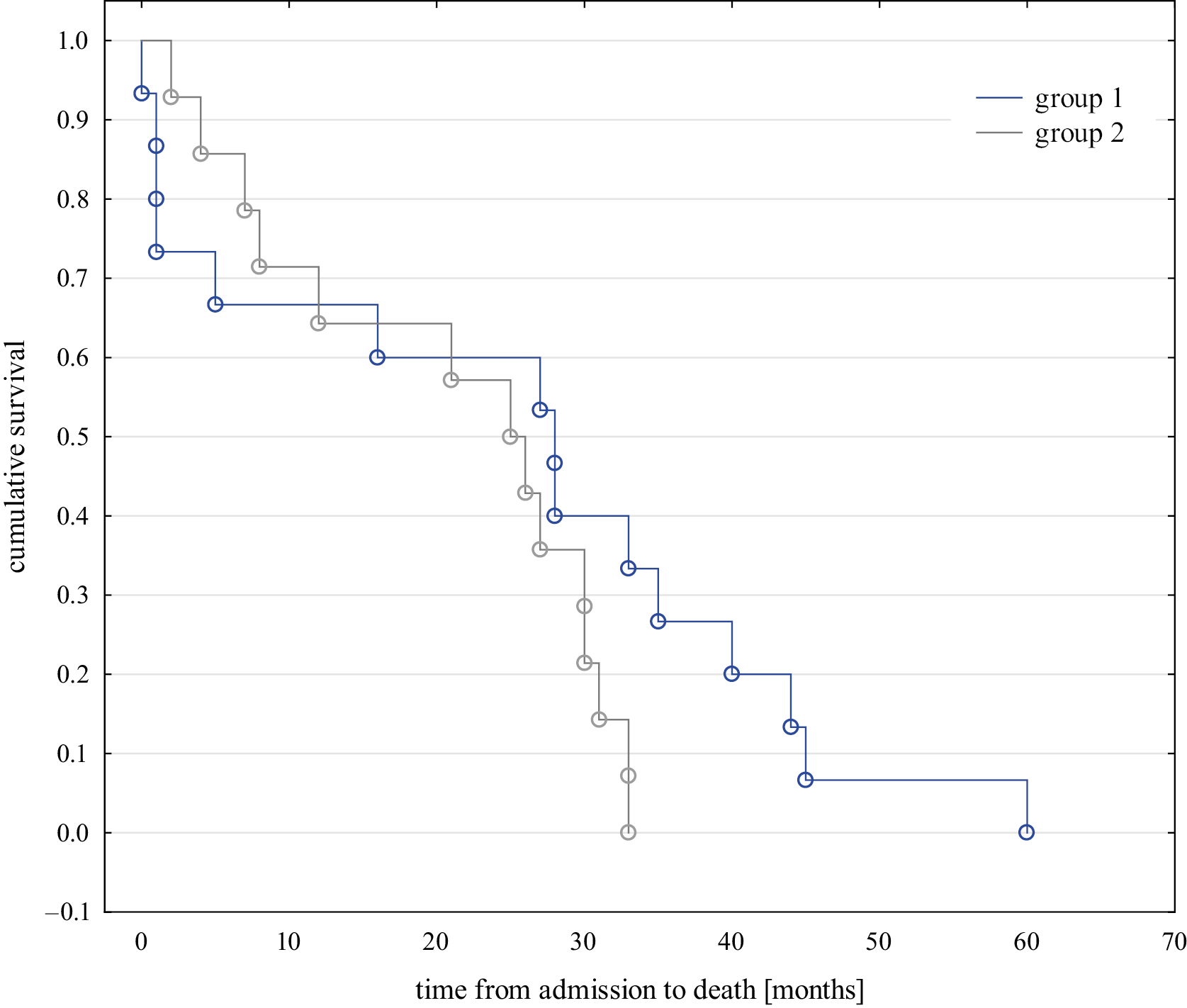

In the follow-up study, no significant differences were observed in the mortality rates between the groups, with 49% in group 1 and 47.5% in group 2 deceased by January 15, 2025. The median interval from admission to death was 28 months (95% CI: 13.1; 42.9) in group 1 and 25 months (95% CI: 15.8; 34.2) in group 2, with no statistical significance observed (the Peto–Peto test p = 0.631, Figure 5). The median interval from initial patient contact to hospital admission was 9 days in group 1 and 11 days in group 2, with no significant difference observed (Peto–Peto test, p = 0.769).

Additionally, second primary malignancies at distinct sites were diagnosed in 8 patients in group 1 and 11 in group 2 (χ2 = 0.055, df = 1, p = 0.814). These comprised predominantly lung cancers (n = 11), 2 skin cancers, two colorectal cancers, and one case each of oral cavity, breast, contralateral vocal cord, and pelvic malignancies.

Discussion

In light of diagnostic and treatment backlogs during the COVID-19 pandemic, we examined whether lung cancer staging one year after the pandemic onset differed from the pre-pandemic period. Our study emphasizes the complexity and demands of the entire treatment process for patients. Patients with LC require long-term follow-up. Additionally, they may need further surgeries in the case of recurrence.

Our previous study found that during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, cancer patients accounted for 29% of all ambulatory visits, and lung cancer patients comprised 15.4% of those visits – more than double the 6.0% observed before the pandemic.10 This trend was associated with the strategy to admit mainly patients with HNC and life-threatening diseases to limit possible SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Surprisingly, our results reveal that no statistically significant differences were found in the cancer stage before and 1 year after the COVID-19 pandemic. Several factors may explain this observation. First, our department remained fully operational throughout the pandemic, including during the initial lockdown – allowing us to treat patients without undue delay. Second, our analysis was limited to hospitalized LC patients and did not include individuals who declined surgery following ambulatory diagnosis or those for whom the multidisciplinary tumor board recommended radiotherapy or chemotherapy. We intend to address these patient groups in future studies. Finally, it may happen that the adverse effects of the pandemic will become visible only in the next few years, due to the fact that LC, especially glottic cancers, take months to develop, but recurrences and secondary primary tumors occur primarily in the first 2 years after treatment.11

Several articles have compared the incidence and the severity of LC before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, but the data are inconsistent.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 No changes in the stage of HNC patients were described in a Canadian study of 2 tertiary centers,16 in an Italian study from the Piedmont Region,17 in the South Tyrol Region,15 and Poland.12 The national study of Dutch HNC patients, with 1,196 patients with LC, showed a lower incidence of LC and other HNC during the pandemic than before, but without significant changes in cancer stage.18 Furthermore, the percentage of treatment modality did not change when comparing the pre- and postpandemic periods.18 On the other hand, Elibol et al. reported more patients in stage T4 in the postpandemic compared to the prepandemic group (30% vs 7%, p = 0.003).13 Moreover, another study from Belgium showed a significant shift to a more advanced stage (clinical stage III) at presentation, but only for men older than 80 years.19 Given an 11.8% underdiagnosis rate among HNC patients during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors of study19 hypothesized that a higher proportion of advanced-stage cases would present in 2021. Overall, the heterogeneity of patient cohorts in these studies, stemming from varied study designs, inconsistent follow-up protocols for LC patients, and differential access to healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic, has complicated the interpretation of global data.

A suitable evaluation of cancer staging is crucial to the choice of an accurate treatment. Few researchers have addressed the problem of disagreement between clinical and pathological TNM.20, 21, 22 Possible causes of this are the lack of ideal imaging that shows 100% of all pathological lymph nodes, inability to detect micrometastases in regional lymph nodes, and inadequate clinical evaluation of tumor invasion into laryngeal cartilages on endoscopy. In our cohort, the concordance rate for cT and pT was 79.1%, and for cN and pN 87.5%, which is a high result. Interestingly, the study in HNC patients shows that the disparity of cTNM and pTNM in at least 1 category of TNM was observed in approx. 50% of the cases, but this study was published in 2017, when the 7th edition of TNM was in effect.20 Celakovsky et al. showed a disparity of 32% in at least 1 characteristic of TNM between clinical and pathological evaluation. Furthermore, the disparity of cT and pT was a significant negative prognostic factor for disease-free survival and disease-specific survival.21 The absence of variations between groups within our study concerning the duration from initial contact to hospitalization, alongside a higher proportion of patients admitted via a fast-track cancer pathway post-pandemic, suggests that cancer patients were prioritized in the diagnostic process and treatment. Significantly, the pandemic did not result in any treatment initiation delays.

In this paper, we observed that the COVID-19 pandemic did not change the number of complications after surgery in the examined time periods. Several studies have shown an increased risk of complications after LC surgeries in the case of secondary treatment or salvage surgery,23 and in malnourished patients compared to well-nourished patients.24 Previous metanalysis25 reported that preoperative radiation therapy, low hemoglobin level, cancer location, that is, supraglottic vs glottic region, were risk factors for pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy. Analogous findings were derived from the Chinese study, indicating that poorly differentiated tumors, diminished preoperative albumin levels, and lymph node cancer invasion not only constitute risk factors for postoperative complications but also serve as independent predictors of mortality risk.26

The occurrence of a second primary cancer in individuals diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the HNC is not uncommon. Literature reports indicate that the standardized incidence ratio within this patient group is 2.2 (95% CI: 2.1–2.2).27 For LC, the excess absolute risk per 10,000 person-years at risk was lower than for the patient with hypopharyngeal cancer (147.8 vs 307.1).27 Furthermore, individuals diagnosed with the second primary tumor exhibit an elevated risk of developing a subsequent one. In our study, during follow-up, a second primary cancer occurred in 16% and 18% of patients in groups 1 and 2, respectively. Similar to the aforementioned study, the predominant site for the second primary cancer in our cohort was the lungs.27 A phenomenon worth investigating will be the assessment of the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 virus on the incidence and course of HNC. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which mediates viral entry into human cells, has been shown to inhibit p53-dependent gene activation. Zhand and El-Deiry theorized that SARS-CoV-2 infection could impact tumorigenesis and modulate responses to chemotherapy.28

Limitations

Interpretation of these data warrants caution due to the study’s small sample size and single-center design. Moreover, our findings cannot definitively exclude a pandemic-related effect on the prevalence of advanced-stage disease, since we did not evaluate patients disqualified from surgery for stage IVC who were referred for chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.

Conclusions

The data presented here show that there are no significant changes in cancer stage in hospitalized patients with LC. Because diagnosis and treatment of patients with LC and HNC were highly prioritized in our department, our health services remained uninterrupted. Despite that, new population-based research is needed to evaluate this topic in a broader sense.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are openly available in Zenodo at doi: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15842821.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available in Zenodo at doi: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15841707.

The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. Flowchart of patient selection.

Supplementary Table 1. Complications during hospitalization.

Supplementary Table 2. Concordance between clinical (c) and pathological (p) T category.

Supplementary Table 3. Concordance between clinical (c) and pathological (p) N category.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.