Abstract

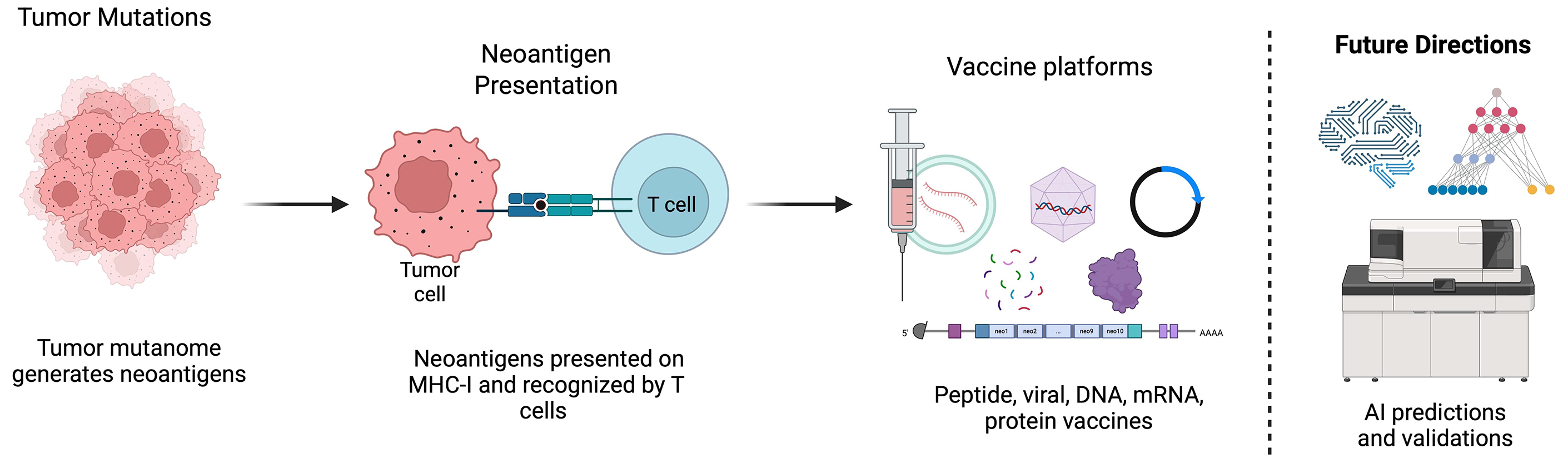

Breast cancer (BC) remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, underscoring the need for novel, more effective therapies. Neoantigen-based immunotherapy – which harnesses tumor-specific somatic mutations to boost immune recognition – has emerged as a particularly promising strategy. Advances in next-generation sequencing and computational immunopeptidomics now allow systematic mapping of the tumor mutanome and rapid identification of immunogenic neoantigens, enabling personalized vaccine design and more precise deployment of immune-checkpoint blockade. However, intratumor heterogeneity, immune-escape mechanisms and the often-limited intrinsic immunogenicity of individual neoepitopes continue to constrain clinical efficacy. This review synthesizes the current landscape of neoantigen-targeted immunotherapies in BC, outlines the principal obstacles to their broader impact and highlights emerging solutions – including improved epitope-prediction algorithms, multi-epitope vaccine constructs and synergistic combination regimens. A deeper understanding of the immunogenic mutanome is expected to translate into more durable and widely applicable treatments for patients with breast cancer.

Key words: breast cancer, personalized immunotherapy, neoantigens, tumor mutanome, tumor mutational burden (TMB)

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women worldwide, accounting for nearly 25% of all cancer cases.1 Despite significant advancements in early detection and treatment, BC remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, particularly in cases of metastatic or recurrent disease.1 The heterogeneity of BC, characterized by distinct molecular subtypes such as hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) and triple-negative BC (TNBC), poses a major challenge for the development of universally effective therapies.2 While targeted therapies and immunotherapies have shown promise, resistance mechanisms and the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) often limit their efficacy.3

In recent years, the concept of the tumor mutanome – the complete set of somatic mutations within a tumor – has emerged as a critical determinant of tumor immunogenicity.4, 5, 6 Mutations in coding regions of the genome can give rise to neoantigens, which are novel peptides presented on the cell surface by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules.7 These neoantigens are recognized as foreign by the immune system, eliciting a T cell-mediated anti-tumor response.4, 5, 6, 7 The identification of neoantigens has opened new horizons for personalized cancer immunotherapy by offering the potential for highly specific and efficacious treatments.

The immunogenic mutanome is particularly relevant in BC, where the mutational burden varies widely across subtypes. For example, TNBC, which is associated with a higher tumor mutational burden (TMB), has been shown to harbor a greater number of neoantigens compared to HR+ BC.8, 9 This difference in mutational load may explain the observed variability in immune infiltration and response to immunotherapy among BC subtypes. However, the relationship between the mutanome and immunogenicity is complex and usually influenced by factors such as MHC diversity, T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire and the composition of the TME.9, 10, 11

Objectives

This review aims to examine the immunogenic mutanome of BC and its role in shaping neoantigen-targeted immunotherapy. Specifically, it: 1) Analyzes tumor-intrinsic and host factors influencing neoantigen immunogenicity and immune escape mechanisms; 2) Explores neoantigen-based therapeutic strategies, including personalized vaccines, adoptive T cell therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors; 3) Identifies key challenges such as tumor heterogeneity, antigen loss and limitations in neoantigen prediction; 4) Discusses future directions involving antigen discovery, multi-omics biomarker integration and combination immunotherapy strategies.

Literature search strategy

This review was conducted as a narrative synthesis of recent literature on the immunogenic mutanome of BC and its implications for neoantigen-based immunotherapy. Studies were selected for their relevance, scientific impact, and contributions to neoantigen discovery, tumor immunology and therapeutic applications. The authors prioritized peer-reviewed original research, review and translational articles published in high-impact journals between 2017 and 2024. While no formal systematic search or Boolean strategy was employed, efforts were made to include a representative range of perspectives and recent advancements in the field. No statistical analyses were conducted, as this is a narrative review based on previously published studies. This is not a systematic review; however, we strived to incorporate diverse perspectives and landmark studies shaping the field of neoantigen-directed immunotherapy in BC.

The mutanome in breast cancer

Breast cancer’s genomic landscape is sculpted by diverse mutational processes, including environmental exposures, DNA-repair deficiencies and endogenous cellular mechanisms.12, 13 These processes contribute to the accumulation of somatic mutations, which collectively constitute the tumor mutanome.12, 13 The mutanome is highly variable between patients, reflecting the unique genetic and environmental factors that influence tumor development.14, 15

Breast cancer is traditionally stratified into molecular subtypes according to the expression levels of hormone receptors – estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR) – and the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).16 These subtypes exhibit distinct mutational profiles and clinical behaviors.17, 18, 19 For example, HR+ BCs, which account for approx. 70% of cases, are characterized by a lower TMB and a predominance of mutations in genes such as PIK3CA and GATA3.19, 20 In contrast, TNBC, which lacks expression of ER, PR and HER2, is associated with a higher TMB and mutations in genes such as TP53 and BRCA1/2.21, 22, 23 HER2+ BCs, which are driven by amplification of the HER2 gene, exhibit intermediate TMB and a unique mutational signature.24

The mutational processes underlying these subtypes are influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Endogenous processes, such as errors in DNA replication and repair, contribute to the accumulation of point mutations and small insertions/deletions.25 Exogenous factors, such as exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation or tobacco smoke, can induce specific mutational signatures.26 In BC, defects in DNA-repair pathways, especially homologous-recombination deficiency (HRD), drive genomic instability and increase TMB.27, 28, 29

Tumor mutational burden, defined as the total number of somatic mutations per megabase of DNA, has emerged as a key biomarker for predicting response to immunotherapy.30 A high TMB is linked to a larger neoantigen repertoire and more robust immune infiltration, especially in cancers such as melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).31, 32 In BC, the relationship between TMB and immunogenicity is more complex, with TNBC exhibiting higher TMB and greater immune infiltration compared to HR+ BC.33, 34, 35 However, even within TNBC, there is significant variability in TMB and immune response, highlighting the need for more precise biomarkers.33, 34, 35

Neoantigen discovery starts with comprehensive somatic-mutation profiling by whole-exome sequencing (WES) or whole-genome sequencing (WGS), which identify single-nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions and structural rearrangements capable of generating tumor-specific neoantigens. However, not all mutations are equally likely to generate immunogenic neoantigens.36 The immunogenicity of a mutation depends on several factors, including its genomic location, its impact on protein structure and its capacity to be presented by MHC molecules.37 Computational algorithms play a critical role in predicting which mutations are likely to generate neoantigens.38 These algorithms use sequence-based and structural-based approaches to predict MHC binding affinity, peptide processing and TCR recognition.38, 39 Commonly used tools include NetMHC, NetMHCpan and MuPeXI, which integrate genomic and transcriptomic data to prioritize neoantigens for experimental validation. Despite advances in computational prediction, the accuracy of these tools remains limited by the complexity of antigen processing and presentation, as well as the diversity of MHC alleles in the human population.

Experimental validation of neoantigens is a critical step in the development of mutanome-based therapies. In vitro assays, such as MHC-peptide binding assays and T cell activation assays, are used to confirm the immunogenicity of predicted neoantigens. The in vivo tumor models including syngeneic mouse models and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), provide additional insights into the anti-tumor activity of neoantigen-specific T cells. However, these models have limitations, particularly in mimicking the complexity of the human immune system and the TME.

Neoantigen discovery and validation

The discovery of neoantigens begins with the comprehensive genomic profiling of tumor tissue. Whole-exome sequencing remains the standard approach for detecting somatic mutations, given its focus on protein-coding regions of the genome, where most neoantigens originate.36 However, WGS provides a more complete picture of the mutational landscape, including non-coding regions that may also contribute to neoantigen generation.40, 41

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is another vital tool as it provides information on the levels of gene expression, ensuring that only mutations in certain genes are included for neoantigen prediction.42, 43 Additionally, proteomics-based approaches, such as mass spectrometry, can directly identify peptides presented on the cell surface by MHC molecules, offering a more direct assessment of neoantigen presentation.44, 45

Despite advances in sequencing technologies, several challenges remain in accurately predicting neoantigens. One major challenge is the broad spectrum of MHC alleles in the human population.46 Each individual expresses unique MHC molecules, which vary in their ability to bind and present specific peptides. Computational tools must account for this diversity, often requiring population-specific databases and algorithms.

Another challenge is distinguishing between clonal and subclonal mutations. Clonal mutations, present in all tumor cells, are more likely to generate neoantigens that can elicit a broad anti-tumor response. In contrast, subclonal mutations, present in only a subset of tumor cells, may contribute to immune escape and therapeutic resistance. Advanced algorithms, such as those incorporating tumor phylogeny, are being developed to address this issue.

Experimental validation is a critical step in confirming the immunogenicity of predicted neoantigens. To assess the affinity of neoantigens for MHC molecules, in vitro approaches such as MHC–peptide binding assays are commonly utilized. T cell activation assays, including ELISpot and intracellular cytokine staining, are used to measure the ability of neoantigens to stimulate T cell responses.47

Although syngeneic mouse models and PDXs have been instrumental in evaluating neoantigen-specific T cell responses, they fall short in replicating the complexity of human immune–tumor interactions. Emerging humanized mouse model platforms may offer more clinically relevant insights into therapeutic efficacy in human settings.48 Humanized mouse models, which are engrafted with human immune cells, offer a more physiologically relevant system for studying neoantigen immunogenicity.49

The therapeutic potential of neoantigen-based approaches in bladder cancer has been highlighted by several studies. Notably, a phase 1b trial by Ott et al. assessed the personalized neoantigen vaccine NEO-PV-01 combined with nivolumab in patients with advanced melanoma, NSCLC and bladder cancer, demonstrating safety, feasibility and immunogenicity. The study demonstrated that the regimen was safe and capable of inducing robust neoantigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, which persisted long-term and exhibited cytotoxic potential.50 Vaccine-induced T cells successfully trafficked to tumors, mediating tumor killing and triggering epitope spreading, an indicator of vaccine-driven tumor destruction.50 Patients with epitope spreading had significantly longer progression-free survival (PFS), and some achieved major pathological responses (MPR), demonstrating substantial tumor reduction.50 Similarly, a recent clinical study identified neoantigens in a patient with metastatic TNBC and used them to generate personalized T cell therapies.51 This study demonstrated that metastatic BC is immunogenic, with most patients generating immune responses to somatic tumor mutations.51 In this phase II trial, adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) reactive to patient-specific neoantigens, combined with pembrolizumab, led to objective tumor regression in 3 of 6 patients, including 1 complete response lasting over 5.5 years. The majority of neoantigen-reactive TILs were CD4+ T cells, highlighting a distinct immunogenic profile in BC.51 Immune escape mechanisms, including human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loss of heterozygosity and downregulation of antigen presentation, were observed in progressing tumors.51 These findings support personalized TIL therapy as a promising approach for treatment-refractory metastatic breast cancer (mBrCa) and warrant further investigation to enhance response rates and overcome immune resistance.51 These findings highlight the potential of personalized neoantigen vaccination to enhance anti-tumor immunity and synergize with PD-1 blockade, supporting its development as an effective immunotherapeutic approach for metastatic solid tumors.50 Discussed studies highlight the potential of mutanome-based therapies in BC and provide a framework for future research.

Immunogenicity of the breast cancer mutanome

Factors influencing neoantigen immunogenicity

The immunogenicity of neoantigens is governed by a dynamic interaction between tumor-intrinsic properties and host immune factors, ultimately influencing the strength and effectiveness of anti-tumor immune responses. Tumor-intrinsic factors include the binding affinity of neoantigens to MHC molecules, the stability of the peptide–MHC complex and the abundance of neoantigen presentation – all of which influence the likelihood of T cell recognition.52, 53 The efficiency of antigen processing, proteasomal cleavage, and TAP-mediated transport further modulates the availability of neoantigen peptides for immune recognition.54 In addition, tumors may develop immune escape mechanisms, such as MHC downregulation, antigen loss variants and altered antigen-processing machinery (APM), to evade immune detection.46 Host factors, including TCR repertoire diversity, the presence of pre-existing T cell clones and the composition of the TME, critically influence immune responses. A diverse TCR repertoire enhances the recognition of neoantigens, while pre-existing T cell clones may provide a rapid and effective immune response.53 Nevertheless, TME exerts immunosuppressive pressure through mechanisms including regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells and immune checkpoint expression, thereby impairing effective anti-tumor immunity and limiting tumor eradication.46 The interplay between TMB and TME composition determines response to immune checkpoint inhibitors and neoantigen-directed immunotherapies.54 Mechanistically, high-affinity neoantigens and a permissive TME support strong T cell responses, while low immunogenicity and immune evasion contribute to poor immune recognition and immunotherapy resistance.52 Understanding these factors is essential for optimizing neoantigen-based immunotherapies – such as personalized neoantigen vaccines and adoptive T cell therapies – to enhance immune recognition and overcome treatment resistance.

The TME plays a critical role in modulating the immune response to neoantigens. Immune-suppressive elements, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and inhibitory cytokines (e.g., tumor growth factor beta (TGF-β) and interleukin 10 (IL-10)), can dampen the anti-tumor immune response.55, 56 Conversely, the presence of TILs, particularly CD8+ T cells, is associated with enhanced immunogenicity and improved clinical outcomes.57, 58, 59, 60

The spatial distribution of immune cells within the TME is also important. For example, the presence of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS), which are organized aggregates of immune cells, is associated with increased neoantigen-specific T cell responses and better prognosis in BC.61, 62, 63, 64 Understanding the spatial and temporal dynamics of the TME is critical for optimizing neoantigen-based therapies.

Immune escape mechanisms

Tumors employ a variety of mechanisms to evade immune detection and destruction. One primary strategy is the downregulation or complete loss of MHC class I molecules, which prevents the presentation of tumor neoantigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), thereby reducing immune recognition. Some tumors also selectively alter the APM, including defects in TAP1/TAP2 transporters, β2-microglobulin (B2M) mutations and impaired proteasomal processing, further diminishing neoantigen display.10, 65, 66, 67 Additionally, tumors upregulate immune checkpoint molecules, such as programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), cytotoxic T cell antigen 4 (CTLA-4), TIM-3, and LAG-3, which suppress effector T cell function by engaging inhibitory receptors on T cells, leading to T cell exhaustion and immune tolerance.10, 65, 66, 67

Beyond checkpoint regulation, tumors also secrete immunosuppressive factors, including TGF-β, IL-10 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which create an immunosuppressive microenvironment by recruiting Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), both of which dampen anti-tumor immune responses.68 Another major mechanism of immune evasion is immunoediting, where the immune system selectively eliminates highly immunogenic tumor cells, leading to the outgrowth of less immunogenic clones with reduced or altered neoantigen expression.69 This process, which involves clonal selection under immune pressure, results in tumors that become progressively more resistant to immune attack and less responsive to neoantigen-based therapies.69, 70, 71

Biomarkers of immunogenicity

Several biomarkers have been proposed to predict the immunogenicity of the BC mutanome.72, 73 These include TMB, which reflects the total number of somatic mutations in a tumor, and PD-L1 expression, a key regulator of immune evasion that influences the response to checkpoint blockade therapy.72, 73 Additionally, the presence of TILs serves as a critical indicator of immune activation and correlates with improved prognosis in BC.74 However, these biomarkers have limitations; e.g., TMB does not always correlate with the presence of highly immunogenic neoantigens, and PD-L1 expression is subject to intratumoral heterogeneity, reducing its predictive power.75 Emerging evidence suggests that a more comprehensive biomarker strategy is required, integrating genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data to better characterize the immune landscape of BC.

Therapeutic strategies exploiting the mutanome

Neoantigen vaccines

Various neoantigen vaccine platforms are being explored – such as peptide-based, mRNA-based, DNA-based, and dendritic cell-based approaches – each with unique strengths and challenges. Peptide-based vaccines offer favorable safety and stability profiles but typically necessitate the use of adjuvants to elicit a robust immune response.76 mRNA-based vaccines have gained attention due to their rapid and flexible manufacturing, but challenges remain in ensuring efficient delivery and stability.76 DNA-based vaccines offer durable antigen expression but have lower immunogenicity and potential safety concerns related to genomic integration.76 Dendritic cell-based vaccines leverage the body’s antigen-presenting cells to elicit robust T cell responses but are complex and expensive to produce.76 Recent studies highlight the potential of combining neoantigen vaccines with immune checkpoint inhibitors or oncolytic viruses to enhance immunogenicity and sustain anti-tumor responses.4, 76 Ongoing clinical trials are assessing the safety and efficacy of these approaches in BC, particularly in TNBC, which has a high mutational burden and greater potential for neoantigen-targeted therapies.4 Mechanistically, the efficacy of neoantigen vaccines relies on optimal antigen selection, MHC binding affinity and T cell priming, emphasizing the need for personalized vaccine strategies to overcome immune evasion and enhance therapeutic efficacy.76, 77

Adoptive cell therapy

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) involves the ex vivo expansion of neoantigen-specific T cells, which are then reinfused back into the patient. This approach has shown remarkable success in other cancers, such as melanoma, and is now being explored in BC. Challenges include the identification and validation of suitable neoantigens and the optimization of T cell expansion protocols. A recent study investigates the challenges associated with expanding neoantigen-reactive TILs in solid epithelial cancers, including BC, where such cells are often rare and exhibit an exhausted phenotype.78 Conventional TIL expansion protocols using anti-CD3 (OKT3) and high-dose IL-2 were found to reduce the frequency of neoantigen-reactive TILs, particularly in BC, due to the outgrowth of bystander T cells and further differentiation toward an exhausted state.78 To address this limitation, the study introduces NeoExpand, a neoantigen-specific stimulation method that selectively expands neoantigen-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ TILs while preserving their stem-like memory phenotypes, which are crucial for sustained anti-tumor immunity.78 In BC-derived TILs, NeoExpand facilitated the recovery and enrichment of p53-reactive T cell clones, which were lost during conventional expansion methods.78 These findings highlight the potential of neoantigen-specific stimulation strategies to enhance the efficacy of adoptive TIL therapy in BC by improving the expansion, persistence and functional capacity of tumor-reactive T cell populations.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as anti-PD-1, anti-PDL-1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, have transformed the treatment landscape for several cancers. In BC, ICIs have shown efficacy in TNBC, particularly in patients with high TMB or PD-L1 expression. Combining ICIs with neoantigen-based therapies may enhance anti-tumor immunity and overcome resistance mechanisms. A study explores the role of TMB as a biomarker for predicting the response of BC to ICIs, emphasizing its limitations and potential clinical utility. While TMB reflects the number of somatic mutations per megabase, only a fraction of these mutations generate immunogenic neoantigens, limiting its predictive accuracy.30 Breast cancer generally exhibits a low TMB, with only 5% of cases exceeding the threshold (≥10 mutations per megabase) associated with improved ICI response.79 However, higher TMB in HER2-positive and TNBCs suggests a greater likelihood of neoantigen presentation, enhanced tumor immunogenicity and increased TILs, which can potentiate responses to checkpoint blockade.80, 81, 82 Mechanistically, the combination of TMB with ICIs, particularly anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies (e.g., pembrolizumab, atezolizumab), enhances T cell activation and tumor clearance.83 Despite these associations, TMB alone is an imperfect predictor of immunotherapy response, as factors such as neoantigen quality, HLA diversity, immune gene signatures, and the TME also influence outcomes.83 These findings support the notion that combining TMB with complementary immune biomarkers, including PD-L1 expression, TIL density and spatial immune architecture, could refine patient selection and optimize the therapeutic benefit of checkpoint inhibitors in bladder cancer.

Limitations

Tumor heterogeneity, both within individual tumors (intratumoral heterogeneity) and across different patients (interpatient heterogeneity), adds another layer of complexity in the identification of universal neoantigens.84 This variability limits the treatment efficacy of shared off-the-shelf neoantigen vaccines, necessitating highly personalized approaches. Additionally, clonal evolution under immune pressure can lead to the emergence of antigen-loss subclones, reducing the durability of neoantigen-targeted therapies and enabling immune escape.85

Developing neoantigen-based therapies requires high-throughput sequencing, computational neoantigen prediction models and experimental validation, all of which are time-consuming, costly and technically demanding.38 Key limitations include inaccuracies in MHC-binding predictions, variable tumor antigen presentation and lack of robust preclinical models to validate neoantigen immunogenicity. These factors hinder the widespread clinical translation of neoantigen-based vaccines and adoptive cell therapies.

Additionally, the nature of neoantigen therapies as a personalized approach raises concerns regarding cost, scalability and accessibility. Efforts to develop off-the-shelf neoantigen vaccines based on publicly shared recurrent mutations and optimize mRNA-based neoantigen platforms may help improve accessibility. Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven neoantigen discovery, validations and advancements in bioinformatics pipelines aim to streamline production to enhance patient selection. Overcoming these challenges is critical to scale up the clinical application of neoantigen-based cancer immunotherapies.

Conclusions

The integration of AI and machine learning into neoantigen prediction algorithms and software holds great promise for improving accuracy and efficiency.86 These tools can analyze large datasets, identify patterns and prioritize neoantigens for experimental validation. Combining genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data provides a more comprehensive understanding of neoantigen and epitope presentation along with their immunogenicity. Multi-omics approaches can identify novel neoantigens and biomarkers, guiding the development of personalized therapies. Furthermore, off-the-shelf neoantigen vaccines that target shared neoantigens expressed in multiple patients, even across different cancer indications, offer a more scalable and cost-effective alternative to personalized vaccines. These vaccines are being explored in clinical trials and have the potential to revolutionize BC immunotherapy.87

The immunogenic mutanome of BC represents a rich source of therapeutic targets with the potential to transform BC treatment. By leveraging advances in genomics, immunology and bioinformatics, significant strides are being made in the development of personalized immunotherapies. While challenges remain, the continued exploration of the mutanome and its interaction with the immune system holds great promise for improving outcomes for patients with BC. A multidisciplinary approach that integrates basic science, clinical data and technological innovation will be essential to fully exploit the immunogenic potential of the BC mutanome.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.