Abstract

Background. Cognitive impairment (CI) is common in patients with alcohol-use disorder (AUD)-related liver cirrhosis, especially those awaiting liver transplantation (LT). There are conflicting results in terms of the role of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) in CI development and persistence.

Objectives. This study investigated the impact of hyperammonemia on CI and evaluated the role of routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in detecting CI among patients with AUD-related cirrhosis listed for LT at a single center.

Materials and methods. Fifty-two adults (36 males, 69%) with AUD-related liver cirrhosis (mean age: 51 ±11 years; mean Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score 16 ±6) were evaluated. Cognitive function was assessed using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III), with scores below 82 indicating probable dementia. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluations focused on cortical-subcortical atrophy, vascular-origin changes, and chronic HE.

Results. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed HE-related changes in 38 patients (73%), vascular-origin changes in 32 patients (62%), and cortical-subcortical atrophy in 15 patients (29%). Cognitive impairment was present in 46 patients (88%), with 30 (58%) suspected of having dementia. Patients with MRI evidence of HE scored lower in the ACE III language subdomain (p = 0.032) and tended toward a higher Child–Pugh classification (p = 0.083). No significant differences were found in ACE-III results or clinical data between patients with and without vascular-origin changes or cortical–subcortical atrophy. Additionally, no correlations were observed between radiological findings, ammonia levels, ACE-III scores, and liver-related mortality.

Conclusions. These findings reveal a high prevalence of CI and significant MRI abnormalities in AUD patients awaiting LT. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of routine MRI in detecting cognitive deficits.

Key words: cognitive impairment, liver transplantation, brain magnetic resonance, alcohol-related liver cirrhosis, blood ammonia level

Background

Alcohol-use disorder (AUD), as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), encompasses maladaptive patterns of alcohol use that lead to significant clinical consequences.1 Chronic alcohol consumption often leads to liver cirrhosis, one of the primary indications for liver transplantation (LT).2, 3 Hepatic encephalopathy (HE), a severe neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with liver cirrhosis, arises from elevated ammonia and inflammation, resulting in low-grade cerebral edema, oxidative/nitrosative stress, inflammation, and disrupted brain oscillatory networks.4 While blood ammonia serves as a biomarker with good negative predictive value for HE,5, 6 alcohol independently causes neurotoxic effects, damaging brain regions such as the frontal lobe, cerebellum and limbic system, including the hippocampus,7, 8 which further impairs brain function. Thus, chronic alcohol use and liver dysfunction are clearly linked to cognitive impairment (CI), likely through disruption of frontal–subcortical circuits and associated neurotransmitter imbalances.

Patients with liver cirrhosis commonly experience CI before LT, with recovery post-transplant varying in extent and timeline.9, 10 The history of HE appears to influence post-transplant recovery of brain function and connectivity.8 Various factors, including minimal and overt HE, chronic alcohol use, and gut microbial dysbiosis, contribute to cognitive impairments in cirrhosis. Prolonged alcohol use is particularly associated with marked deficits in executive function, attention, motor skills, spatial reasoning, language, and memory.11, 12 Alcohol-induced neuroinflammation further reduces hippocampal white matter and prefrontal cortex volume, impairing memory and decision-making abilities.7, 13 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains a valuable tool for monitoring brain changes and evaluating recovery potential after transplantation, underscoring its importance in elucidating the neurobiological basis of CI in alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) and HE. Despite its clinical importance, detailed analysis of brain MRI findings is not readily available in routine practice.

In ALD, chronic alcohol consumption leads to significant cognitive deficits, particularly in executive function, memory and attention, through neurotoxic effects that disrupt glutamate and GABA neurotransmitter balance and impair the frontal–subcortical circuits essential for cognitive processing and behavioral regulation.13 Alcohol also induces brain inflammation and oxidative stress, leading to structural and functional alterations. MRI studies show that patients with ALD often exhibit reduced gray matter in the frontal cortex and subcortical regions, changes that correlate with cognitive decline and increased susceptibility to HE.13

In HE, elevated ammonia disrupts astrocyte function, leading to increased glutamine levels, astrocyte swelling, and cerebral edema.13 These changes impair neurotransmitter metabolism, manifesting as deficits in attention, reaction time and executive function. Hepatic encelopathy-related CI is associated with MRI abnormalities in the basal ganglia due to manganese deposition from chronic liver disease.14 Ammonia accumulation also disrupts dopaminergic, glutamatergic and serotonergic pathways, further affecting frontal–subcortical circuits critical for cognitive processing.14, 15

The MRI findings in HE patients frequently show basal ganglia abnormalities and cerebral edema, likely from astrocyte swelling and metabolic disruptions.14, 15 Even after transplantation, cognitive impairments, particularly in attention and executive function, often persist and are associated with reduced volumes in the frontal lobe and basal ganglia.14, 15 Cognitive deficits in ALD and HE primarily result from disruptions in frontal–subcortical circuits caused by alcohol-induced dysregulation of glutamate and GABA, compounded by the neurotoxic effects of ammonia, as noted above. Ammonia also damages astrocytes, which are essential for detoxification and neurotransmitter balance, further impairing neural communication between the basal ganglia and frontal cortex.15 The impact of ammonia on astrocyte function underscores the need for early intervention to prevent cognitive decline in LT candidates.

Objectives

This study examines the predictive value of 3-point routine brain MRI evaluations for cognitive impairment in consecutive liver transplant candidates with alcohol use disorder-related liver cirrhosis at a single transplant center.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 52 adult patients (69% male, comprising 36 men and 16 women) with a mean age of 51 ±11 years, all diagnosed with AUD-related liver cirrhosis, were identified as potential candidates for LT in a single liver transplant center. The mean Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 16 ±6, indicating an advanced stage of liver disease in the study cohort. The main indication for LT assessment in AUD patients was chronic liver failure (87%). However, 13% of patients had hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as the indication for LT.

Study design

All patients included in this cross-sectional, single-center study were admitted in 2023 to the Department of Hepatology, Transplantology, and Internal Medicine at the Medical University of Warsaw (Poland) for evaluation prior to listing for liver transplantation (LT). The work-up included biochemical and serological testing, cardiology and pulmonology assessments, and imaging studies, including brain MRI. The exclusion criteria included regular intake of hypnotics, severe overt HE and psychiatric or neurodegenerative diseases, making it impossible to perform the investigation. Blood ammonia levels were routinely measured as part of the laboratory work-up for all participants.

Cognitive assessment

Cognitive function was assessed using the Addenbrooke Cognitive Examination III (ACE III), which is a comprehensive tool designed to detect CI across various domains. A cutoff score of less than 82 on the ACE III was utilized to identify patients with a high likelihood of dementia. The ACE III covers cognitive domains such as attention, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuospatial abilities. The Polish version is available free of charge.16 The ACE-III has been previously validated against standard neuropsychological tests.17 In addition, our center has prior experience with this tool, reflected in previously published projects.18, 19 All patients were routinely examined during their stay in the hospital by a psychiatrist dedicated to the transplant program, according to the pre-transplant work-up protocol, which consists of full psychiatric consultation, as well as the ACE III tool. The “liver-related mortality” was defined as a death occurring during the study.

Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation

Each patient underwent brain MRI using Siemens Magnetom Avanto 1.5T (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) as part of their routine pre-transplant assessment. The MRI scans were evaluated using a standardized 3-point approach, focusing on the assessment of cortical-subcortical atrophy, a semi-quantitative evaluation of vascular-related changes, and the identification of features consistent with chronic HE. All MRI images were analyzed by experienced radiologists blinded to the cognitive functions assessment results and venous blood ammonia level. Organic brain changes in MRI, including cortical-subcortical atrophy, vascular-origin alterations and HE-related abnormalities, were systematically assessed and described using the Fazekas scale to ensure clarity and reproducibility. The results from these MRI scans were then correlated with cognitive test scores and clinical parameters.

Blood ammonia measurement

Fasting venous blood samples were collected from all subjects to assess blood ammonia concentration. Measurements were performed in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) plasma using the enzymatic glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH) method on the Dimension EXL analyzer (Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany). Reference values were 19–55 μg/dL.

Ethics

Appropriate informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Warsaw (approval No. KB/81/2022 and amendment No. KB42/A 2025) and was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (6th revision, 2008).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) and Python v. 3.10 (https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3100; SciPy and StatsModels packages) for advanced corrections. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Due to the non-normal distribution of key variables, including MELD, ACE III scores, and blood ammonia levels, nonparametric tests were applied for both group comparisons and correlation analyses.

Continuous variables are presented as median (Q1–Q3) for non-normally distributed data and as mean ± standard deviation (SD) when normally distributed. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers and percentages.

Group comparisons between patients with positive (ACE III < 82) and negative screening results were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, depending on expected cell frequencies. The χ2 test assumptions were verified by calculating expected frequencies, which are presented in the Supplementary Table 1 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17104342).

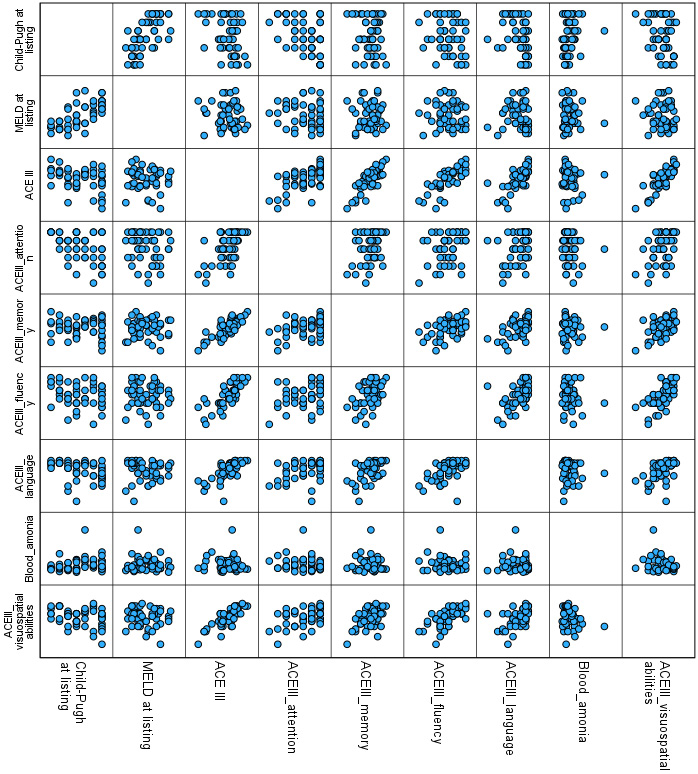

Correlations were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient due to the nonparametric nature of the data. The analyses examined associations between MRI features (HE signs, vascular-origin changes and cortical–subcortical atrophy) and ACE-III total and domain scores; clinical parameters (Child–Pugh score, MELD score and blood ammonia) and cognitive function; and ACE-III total scores and both radiological features and clinical variables.

To control for multiple comparisons, the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied across all sets of correlation analyses and group comparisons involving multiple variables. This method was chosen over Bonferroni to maintain statistical power while limiting false discoveries in an exploratory context.

Statistical results are reported with appropriate test statistics (U, χ2, r), degrees of freedom where relevant and p-values rounded to 3 decimal places. The p-values less than 0.001 are reported as p < 0.001. An FDR-corrected p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and such results are marked with an asterisk in the tables.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the study cohort are summarized in Table 1. The median Model of End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium (MELD-Na) score was 16 (Q1–Q3: 12–19) points, while the median Child–Pugh score was 8 (7–9) points. The median venous blood ammonia concentration was 83.5 µg/dL (Q1–Q3: 53–108), with 24 patients (46%) showing hyperammonemia, defined as > 55 µg/dL.

The median ACE III score across the entire cohort was 79 points (Q1–Q3: 69–88); 46 patients (88%) displayed impaired cognitive performance, as indicated by an ACE III score below 89 points, and 30 patients (58%) met the criteria for high probability of dementia, defined by an ACE III score below 82 points.

Radiological signs consistent with HE were observed in brain MRI scans of 38 patients (73%). These patients did not significantly differ from others in terms of age, sex, venous blood ammonia levels, MELD-Na scores, or total ACE III results (Mann–Whitney U test or Pearson’s χ2 test; all FDR-corrected p > 0.05). Although the uncorrected analysis showed lower language domain scores in patients with radiological signs of HE (U = 207.5, p = 0.032), this association was no longer significant after correction for multiple comparisons (FDR-adjusted p = 0.067). Similarly, a trend toward higher Child–Pugh classifications in these patients (U = 338.5, uncorrected p = 0.083) did not reach statistical significance after FDR correction.

Spearman’s correlation analyses revealed no statistically significant associations, after correction for multiple comparisons, between any of the evaluated MRI features (HE, vascular-origin changes, cortical–subcortical atrophy) and ACE III total or domain scores. Full results are presented in Table 2.

Vascular-origin changes were reported in 32 patients (62%). Uncorrected comparisons showed a significant association with lower total ACE III scores (χ2 test, p = 0.045), but this finding was not significant after FDR correction (adjusted p = 0.090). No associations were found between vascular-origin changes and clinical variables or hyperammonemia (FDR-adjusted p > 0.05).

Cortical–subcortical atrophy was identified in MRI scans of 15 patients (29%). Uncorrected analyses showed an association between atrophy and CI (χ2 test, p = 0.038), but this finding did not remain significant after FDR correction (adjusted p = 0.081). No significant relationships were observed between cortical-subcortical atrophy and age, sex, ammonia levels (quantitative or categorical), MELD-Na, or Child–Pugh scores.

Table 3 presents the correlations between ACE III total and domain scores with clinical parameters, including blood ammonia, MELD-Na, and Child–Pugh scores. No significant correlations were observed between ammonia or MELD-Na and cognitive performance (Spearman’s r, all FDR-adjusted p > 0.05). While uncorrected correlations suggested a relationship between Child–Pugh scores and ACE III total, attention, language, and visuospatial abilities, none of these remained significant after FDR correction. Scatterplots illustrating selected relationships between cognitive domains and clinical/imaging features are presented in Figure 1.

Five patients (9.6%) died during the study period, all following liver transplantation due to infection and/or surgical complications. No significant differences in mortality were found between patients with or without radiological signs of HE, vascular-origin changes or cortical-subcortical atrophy, nor between CI groups (ACE III < 82 vs ≥ 82) (Pearson’s χ2 test, all p > 0.05).

Discussion

The findings from this study confirm a high prevalence of CI among liver transplant candidates with end-stage liver disease (ESLD) related to AUD. This homogeneous cohort of AUD patients revealed a concerning frequency of structural brain changes on routine MRI. While numerous studies have investigated cognitive dysfunction in patients with hepatitis C and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) using advanced imaging techniques (e.g., magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), functional MRI,20, 21, 22 such tools remain largely unavailable in routine pre-transplant care. Most standard clinical brain MRI reports do not include quantitative metrics such as mean diffusivity or fractional anisotropy.23, 24 Therefore, our study underscores the value of assessing cognitively vulnerable ESLD patients using accessible and widely available neuroimaging tools.

Our data showed that vascular-origin changes and cortical-subcortical atrophy were frequent, even in a relatively young population (mean age: 51 years). Additionally, a striking proportion of patients demonstrated moderate-to-severe CI, with more than half meeting criteria for high dementia probability based on ACE III. This level of dysfunction may impact transplant candidacy through impaired treatment adherence and increased post-transplant risks, including graft rejection.10

Contrary to our initial assumptions, no significant correlations were found between radiological features and cognitive test scores after correction for multiple comparisons. Although patients with signs of HE showed lower scores in the language domain of the ACE III in uncorrected analysis, this finding did not remain statistically significant following FDR adjustment. Similarly, no MRI feature (including vascular-origin changes and atrophy) was significantly associated with cognitive performance in domain-level correlations.

These findings align with the growing understanding that blood ammonia levels, often central to the HE narrative, are unreliable markers of cognitive status in ESLD.4, 5, 6 Our study confirms that ammonia levels were not correlated with ACE III total or domain scores, reinforcing the notion that multiple metabolic and systemic variables confound its interpretation.25

Contributing factors include individual variation in urea cycle function, dietary protein intake and hydration status, all of which can affect ammonia levels without reflecting cognitive decline. Additionally, limited access to anti-ammonia therapies (e.g., lactulose, rifaximin), whether due to cost constraints or poor adherence, may further confound this relationship in real-world settings.

The role of HE in long-term CI remains debated. Although LT improves ammonia clearance, persistent deficits post-transplantation have been widely reported.12, 26 Some studies suggest that structural brain damage from prior HE episodes may be irreversible,9, 27 whereas others report partial reversal of MRI abnormalities after transplantation.28 Notably, Bajaj et al.29 found that episodes of overt HE led to persistent deficits in working memory and response inhibition. Similarly, studies by Adejumo et al.30 and Lopez-Franco et al.31 point to a relationship between HE and dementia that may persist beyond the transplant period. However, evidence remains conflicting. While Ko et al.32 did not find a clear link between pre- and post-transplant cognition, Berry et al.33 highlighted pre-transplant CI as the strongest predictor of post-transplant dysfunction. Cheng et al.34 demonstrated persistent abnormalities in functional brain connectivity in patients with prior HE, especially in regions responsible for higher-order cognition.

Our analysis identified a consistent, though uncorrected, association between cognitive performance and liver functional reserve, particularly the Child–Pugh score. This aligns with known links between advanced liver dysfunction, metabolic alterations and cognitive deficits.35, 36 However, after FDR correction, these associations lost statistical significance, suggesting the need for cautious interpretation. The trend may reflect the combined impact of malnutrition, systemic inflammation and energy metabolism deficits.11, 37

The MELD score, which does not account for albumin or nutritional status, was not related to cognitive outcomes. This discrepancy further supports the theory that chronic nutritional deficits, captured in part by the Child–Pugh classification, may be more relevant in assessing cognitive vulnerability in this population. The high prevalence of CI in our ESLD cohort also exceeds that reported in kidney transplant recipients.38

Limitations

This single-center study addressed a critical gap in transplantology by focusing on AUD patients with ESLD – a clinically uniform group often underrepresented in cognitive research. Nevertheless, the sample size limits generalizability, and the lack of comprehensive neuropsychological testing or DSM-5-based diagnoses precludes a definitive classification of cognitive disorders.

While the ACE III is a robust screening tool, it cannot replace a detailed diagnostic evaluation. Additionally, the cross-sectional design prevents inferences regarding the trajectory of cognitive dysfunction, either pre- or post-transplant. Further studies should explore how routine MRI findings relate to post-LT outcomes, particularly in the presence or absence of HE history.

Conclusions

This study confirms the high prevalence of CI among liver transplant candidates with ESLD. Although structural brain abnormalities were frequently observed, they were not significantly associated with cognitive test outcomes after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Similarly, blood ammonia levels did not predict cognitive function.

Although subtle trends were observed between the Child–Pugh score and ACE III performance, these did not reach statistical significance after FDR correction. Our findings support growing evidence that cognitive dysfunction in ESLD may be multifactorial, involving metabolic, nutritional and neuroinflammatory pathways beyond hyperammonemia alone. Future research should aim to refine neuroimaging biomarkers and integrate broader systemic assessments to better characterize cognitive risk in this vulnerable population.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17104342. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Expected frequencies for categorical variables analyzed with the χ2 test.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

During the preparation of this work the authors used Chat GPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.