Abstract

Background. Basket trials are an innovative type of clinical trial primarily used in oncology. A distinctive feature of these studies is the grouping of patients based on specific molecular characteristics, such as genetic mutations or immunological subtypes, rather than traditional criteria like the type of cancer.

Materials and methods. This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Medical databases were searched for studies published between 2014 and 2024. The inclusion criteria focused on basket trials as a clinical trial model in oncology.

Objectives. This work aims to outline the principles of conducting basket trials in oncology, analyze basket trials from the past decade, and highlight the emerging trends in this type of trial.

Results. The analysis of 76 articles meeting the inclusion criteria revealed that most of these studies are conducted as phase II clinical trials. The average duration of the basket trials in the analysis was 5.9 years (mean = 5.05), with an average recruitment target of 326 patients (mean = 123.5). Most of these studies were conducted in the USA, and the majority of basket trials focused on patients with solid tumors.

Conclusions. The systematic review confirms that basket trials have significant potential as a clinical trial model, as evidenced by the increasing number of basket trial projects being conducted.

Key words: cancer clinical trials, basket trials, basket and umbrella trials

Background

Basket trials are an innovative type of clinical trial primarily used in oncology. A key feature of these studies is the grouping of patients based on specific molecular characteristics, such as genetic mutations or immunological subtypes, rather than traditional criteria like the type of cancer.1 The growing use of precision medicine to identify and develop effective targeted therapies defines the current landscape of pharmaceutical drug development. This innovative approach aims to enhance treatment effectiveness by tailoring therapy to the patient’s unique molecular profile, rather than relying on standard treatment regimens designed for patients with cancer in a particular location, such as lung or colorectal cancer.

Innovations in biotechnology, clinical trials and advanced computational tools have the potential to accelerate the discovery and development of new targeted therapies. One example of methodological innovation is the design of master protocols2 – studies that simultaneously assess the effects of multiple investigational drugs across various cancer types within a single overarching framework. The main protocols in oncology enable the identification of specific signaling pathways closely associated with gene variants responsible for tumor development, growth, and progression of cancer cells.3 Designs of these master protocols, such as basket trials or umbrella trials, facilitate the personalization of patient therapy, which may lead to improved clinical outcomes and better optimization of available drugs.

Basket trials aim to use therapies targeting specific molecular changes in cancer patients, regardless of the tumor’s origin in the body.4 One example of a basket trial is the use of imatinib across various histological subtypes of advanced sarcoma,5 or vemurafenib in the treatment of cancers other than melanoma that harbor the BRAF V600 mutation.6

Basket trials represent the next stage in the evolution of precision medicine, enabling clinicians to select effective treatments based on a patient’s genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. As precision medicine advances, the role of artificial intelligence (AI) has become increasingly important. AI-based solutions can enhance cancer treatment and management, which is why their use is recommended in various areas, including personalized medicine.7 Despite these advancements, significant gaps remain in understanding the broader implications of basket trial designs in clinical practice. While numerous studies have demonstrated the potential of basket trials in specific tumor types, comprehensive reviews addressing their overall efficacy, methodological challenges and emerging trends in oncology remain limited.

Basket trial study model

A basket trial design selects patients based on specific molecular biomarkers, grouping them according to common molecular characteristics, and then treating all patients in a given group with the same therapy or a set of different drugs. Basket trials can be single-arm or multi-arm, where each arm represents a separate ‘basket’ that, regardless of the disease type, brings together patients to test a specific treatment based on their shared genetic characteristics.8, 9 The term ‘basket’ thus refers to the grouping of potentially different cancers into one unified disease at the molecular level (Figure 1).

Objectives

This study aims to address these gaps by conducting a systematic review of basket trials published between January 2014 and June 2024. Specifically, it seeks to provide an overview of the methodological principles underlying basket trials in oncology, as well as analyze the scope, effectiveness and geographical distribution of these trials to identify trends and areas requiring further exploration, and highlight the role of AI and technological advancements in enhancing the design and outcomes of these trials. By examining the evolving landscape of basket trials, this study aims to provide critical insights into their potential as a cornerstone of precision oncology, while contributing to the advancement of molecular profiling applications in clinical practice.

Methods

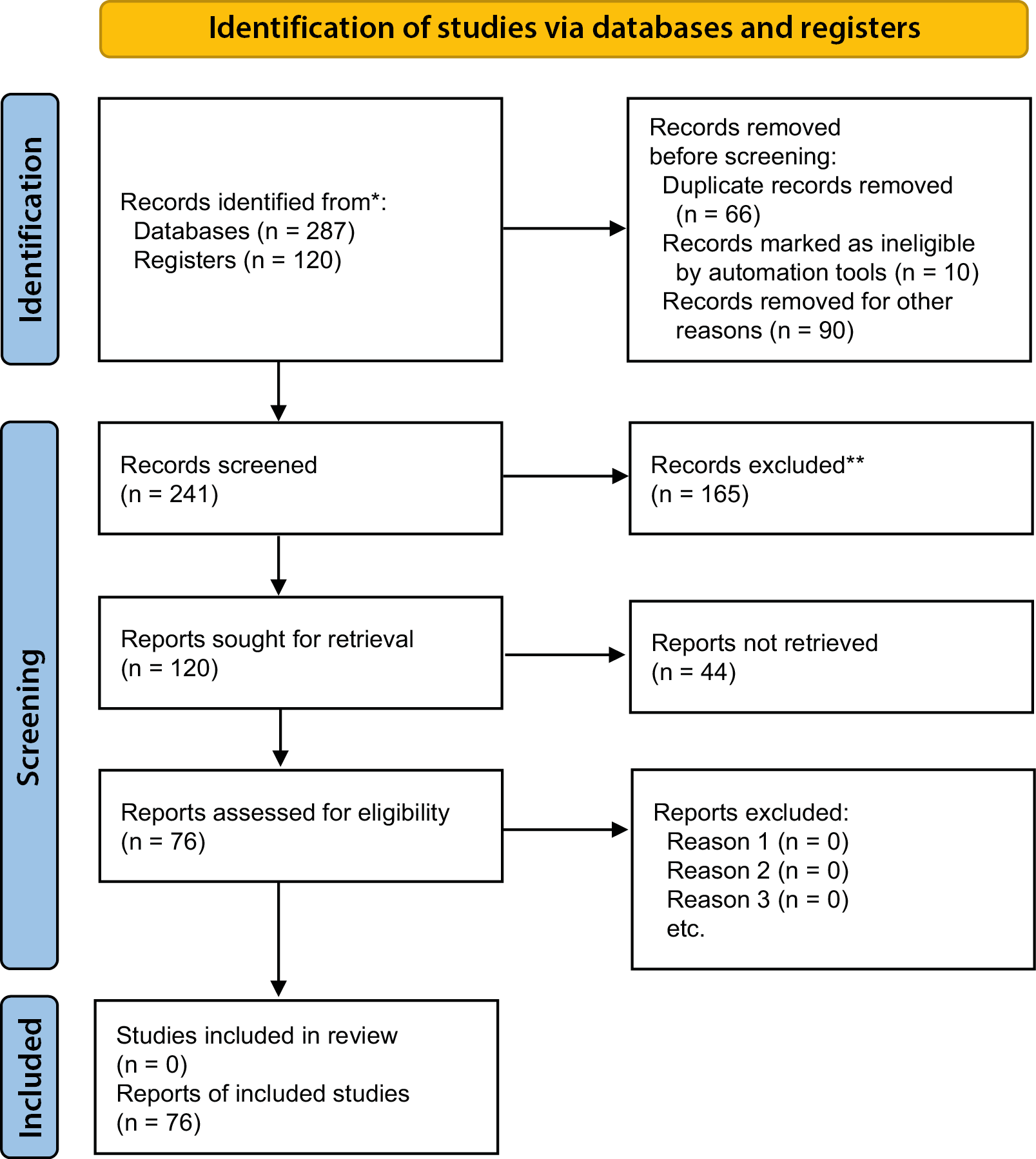

In March 2024, a systematic review of basket studies conducted between January 2014 and June 2024 was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A total of 241 records were identified (Figure 2). The review was conducted across four major databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) as well as the clinical trial registry ClinicalTrials.gov.

Eligibility criteria

The study analyzed relevant publications from January 2014 to June 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) the basket trial model was clearly described in the abstract or title of the publication, 2) the study involved cancer clinical trials and 3) the publication was in English.

Search strategy

The database search strategy was defined using keywords in the title or abstract, including “basket trials”, “clinical trials”, “basket trial”, and “basket study”. The concept of a basket study had to be clearly defined in the title or abstract of the study. The results were filtered by language, and only studies published in English were included. Four databases were used: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, as well as the clinical trial registry database ClinicalTrials.gov. The same keywords were used to search for publications across each database.

The articles found in the databases were initially screened by reviewing their titles and abstracts. The authors assessed the inclusion criteria to select publications that could meet these criteria. Articles deemed relevant to the proposed topic were then read in full. Below, basket studies conducted among patients with the most common and rare cancers will be briefly summarized.

Results

The analysis identified 76 basket studies that met the criteria for inclusion in the systematic review. The majority of these studies were phase II trials (n = 45, 76%), with nearly 1/5 (n = 15, 19%) being early extended phase I/II studies. The remaining studies included phase I trials (n = 6, 7.6%) and phase III trials (n = 2, 2.6%). One study (n = 1, 1.3%) was observational. Most of the studies were conducted in an open-label model (n = 70, 92.1%), and 9.2% were performed as academic research.

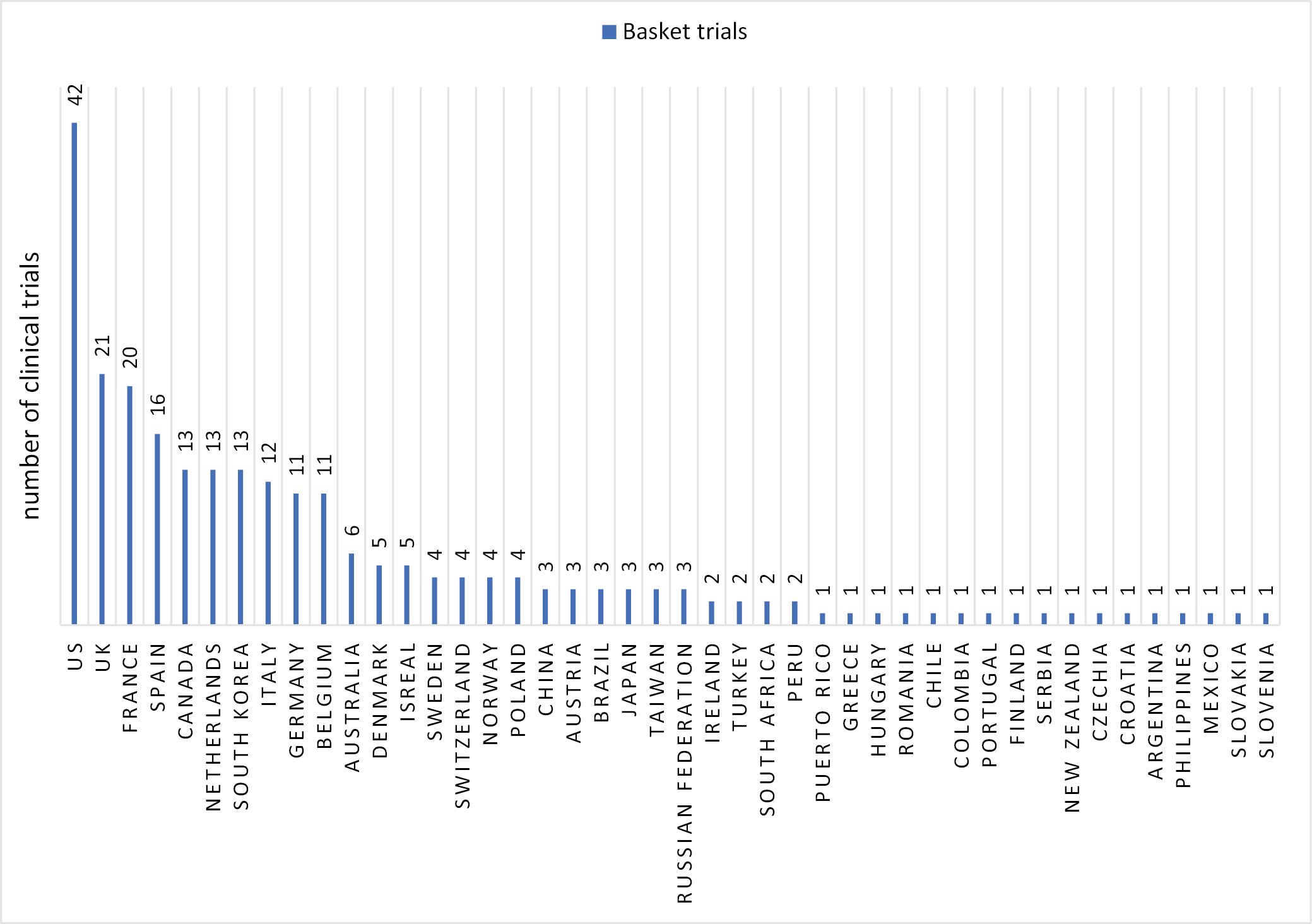

The average duration of basket trials in the included analysis is 5.9 years (mean = 5.05), while the average recruitment target is 326 patients (median = 123.5). On average, approx. 3 countries were involved in conducting each basket trial. Additionally, an average of 3.1 treatments were used in the studies. The USA accounted for the largest number of basket studies in the analysis (n = 42, 55.2%), followed by the UK (n = 21, 27.6%) and France (n = 20, 26.3%). The chart below shows all countries where basket trials in oncology have been conducted (Figure 3).

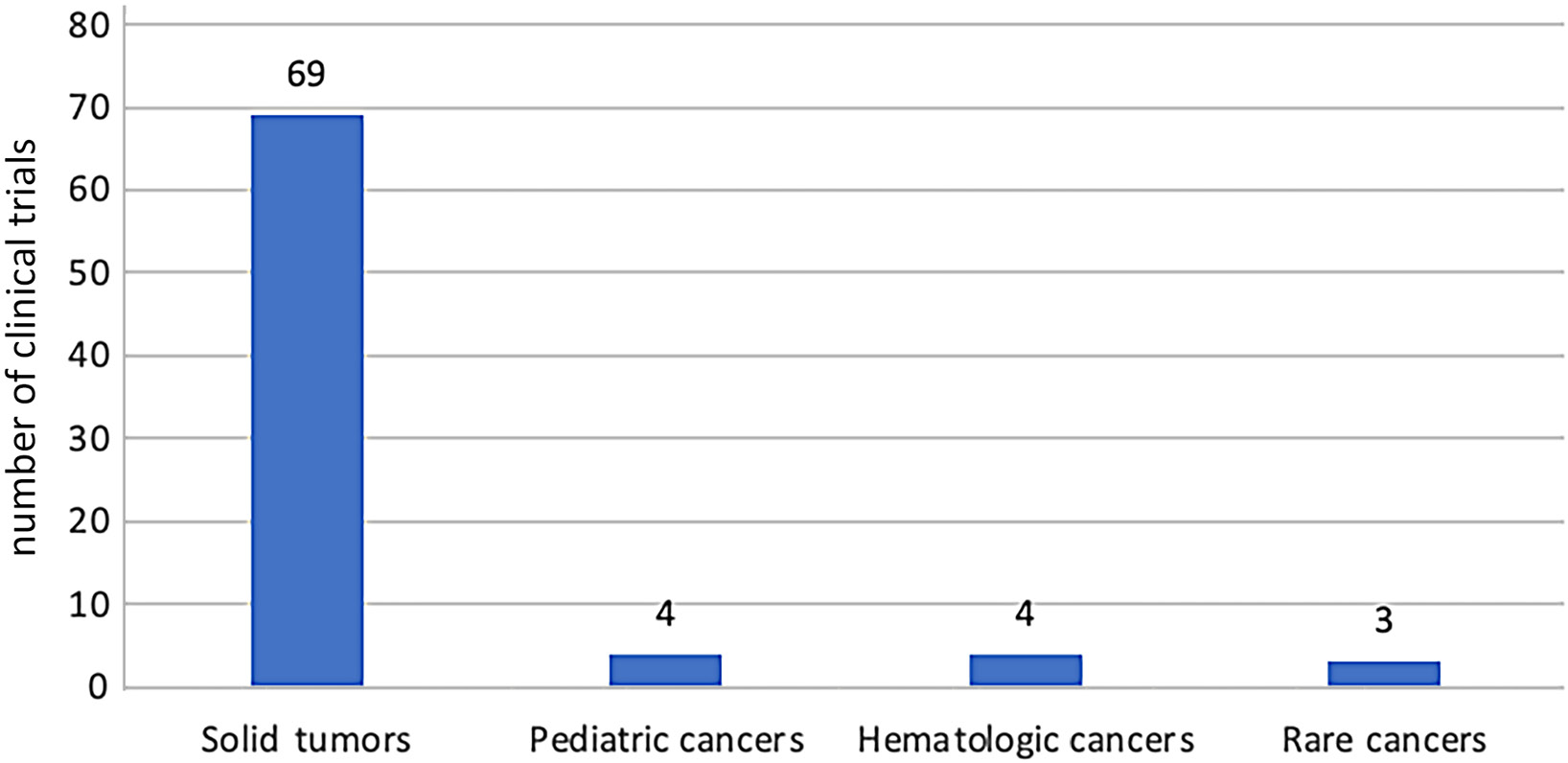

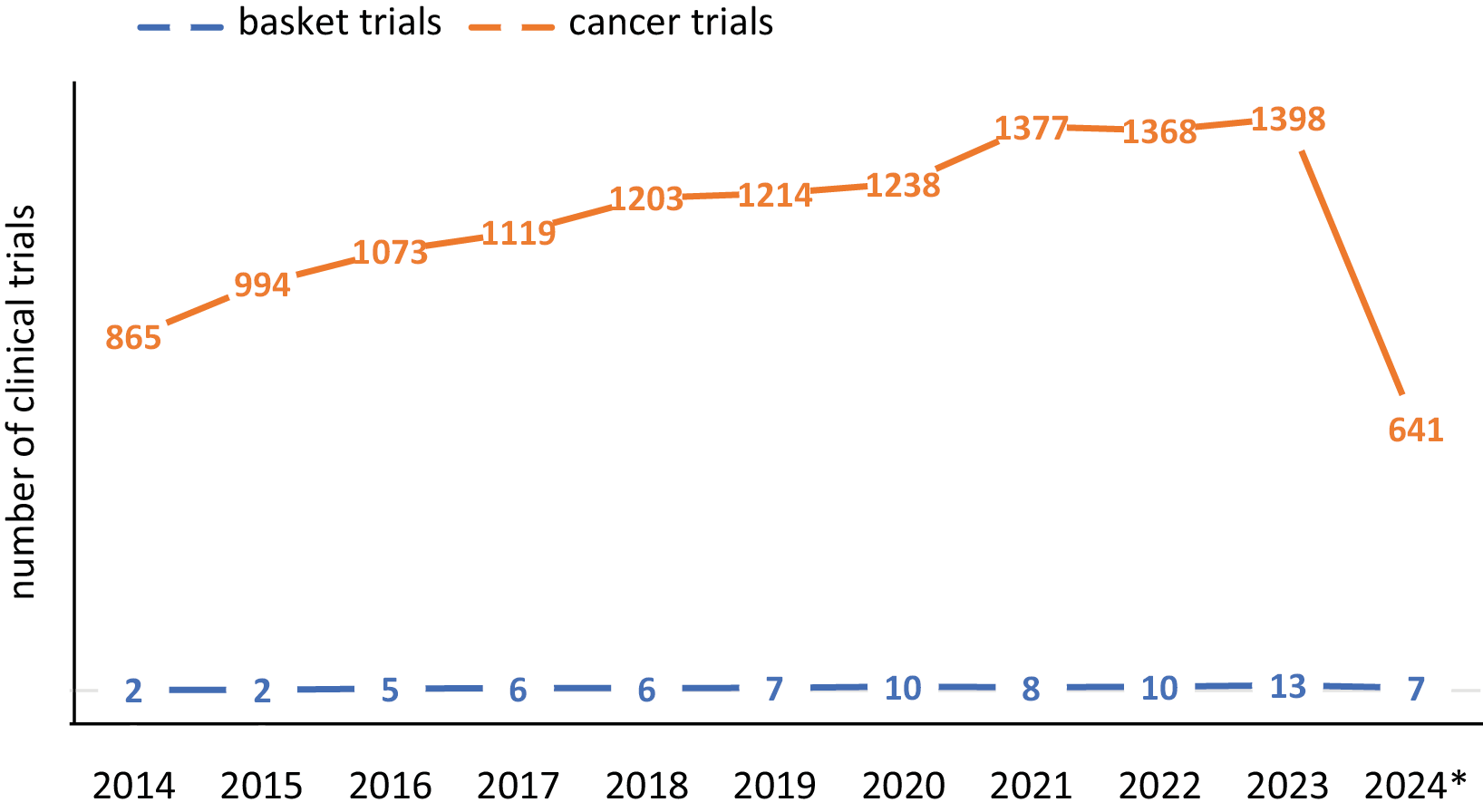

In basket studies, there is typically no fundamental division of cancer based on the location of the primary tumor. Therefore, the table below includes the cancer types listed as inclusion criteria in the basket study. Most basket trials are focused on patients with solid tumors (n = 69, 90%) (Figure 4). The trend of the basket trial model in oncology was also analyzed. In 2023, 0.9% of oncology studies were conducted using the basket model. Since 2020, the number of studies conducted in the basket model has averaged 10.2 per year in oncology (Figure 5).

One example of a basket study in the above analysis is the NCT02693535 study. The Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) study is a non-randomized clinical trial designed to determine the safety and effectiveness of commercially available targeted anticancer drugs in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer that has a potentially actionable genomic variant.

The TAPUR trial aims to analyze U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved targeted therapies developed by collaborating pharmaceutical companies, catalog clinical oncologists’ molecular profiling test selections, and generate hypotheses for additional clinical trials. The study’s recruitment goal is 3,791 patients, the largest number of patients in any basket study included in this analysis. The study is scheduled to last 9 years and 6 months. Fisher et al. presented partial results from the TAPUR trial for patients with advanced breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and ovarian cancer using cetuximab therapy. Patients with breast cancer (n = 10), non-small-cell lung cancer (n = 10) and ovarian cancer (n = 29) were enrolled in the study between June 2016 and September 2018. No objective responses or disease stabilization for at least 16 weeks were observed in any cohort of patients without KRAS, NRAS, or BRAF mutations (Table 1).10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Chung et al. presented partial results from the KEYNOTE-158 phase II basket trial, which recruited patients with advanced cervical cancer who had previously undergone therapy due to tumor dissemination. The study included 90 patients who received pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks for up to 2 years or until progression, intolerable toxicity, or discontinuation by the physician or patient. Pembrolizumab monotherapy demonstrated durable antitumor activity and manageable safety in patients with advanced cervical cancer. Based on these results, FDA granted accelerated approval of pembrolizumab for patients with PD-L1-positive advanced cervical cancer who progressed during or after chemotherapy.12 The total recruitment target for the NCT02628067 Advanced Solid Tumor Basket Study is 1,609 patients, and the study is scheduled to last 10 years and 10 months.

Another example of a basket study of advanced solid tumors is the study by Sweeney et al., which focused on cancer patients with HER2 amplification, overexpression, and/or activating variants. The study (NCT02091141) included 346 patients. The study demonstrated that pertuzumab + trastuzumab had activity in various cancers with HER2 amplification and/or overexpression and wild-type KRAS, with a range of efficacy depending on the tumor type. However, it also showed limited activity in patients with KRAS variants, variants in the HER2 gene, or in those with HER2-low (Score 1+) or ultra-low (Score 0) status.13

Oaknin et al. also presented partial results of a study on variants in the HER2 gene in this case of cervical cancer. The SUMMIT trial (NCT01953926) is a phase II study evaluating the efficacy and safety of neratinib as monotherapy or in combination with other therapies in participants with solid tumors with a variant in the HER gene (EGFR, HER2). The study included 16 patients with cervical adenocarcinoma. Neratinib monotherapy showed activity in previously intensively treated patients with cervical cancer with a variant in the HER2 gene.15 The overall recruitment goal of the SUMMIT study is 582 patients. The SUMMIT trial was terminated at the beginning of 2023.

Others basket trials

Pediatric cancers

One example of a basket study in a pediatric group is the NCT03363217 study described by Perreault et al. This is a phase II study of trametinib in patients with pediatric glioma or plexiform neurofibroma, specifically those with treatment-resistant tumors and activation of the MAPK/ERK: TRAM-0 pathway. The main objective of the study is to determine the objective response rate to trametinib as a single agent in the treatment of progressive/refractory cancers with MAPK/ERK pathway activation.16 The recruitment target is 114 patients, and the study is planned to last 9 years. A clinical trial is ongoing.

Rare cancers

Rare cancers pose a significant challenge for accurate diagnosis and treatment. While there is no universal definition, the American Cancer Society (ACS) defines rare cancers as those with an incidence of fewer than 6 cases per 100,000 people per year.17 Basket trials present an opportunity to identify appropriate molecularly targeted treatments for patients with rare cancers.

In the phase II study NCT02721732, patients with advanced rare cancers who had progressed on standard therapies within the last 6 months were enrolled in 9 cohorts of cancer patients, with a 10th cohort for those diagnosed with other rare lesions. The study included 127 patients who received pembrolizumab at a dose of 200 mg intravenously every 21 days. The favorable toxicity profile and antitumor activity observed in patients diagnosed with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, cancer of unknown primary, and paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma support further evaluation of pembrolizumab in this patient population.18

Hematological cancers

Another group of cancers in which the basket model of a clinical trial is used is hematological cancers. The phase II trial NCT00866047, published by Pro et al., evaluated the safety and efficacy of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). Fifty-eight patients were included in the study; brentuximab was administered to patients every three weeks as a 30-min intravenous infusion for a maximum of 16 treatment cycles. The results showed a high rate of resolution of peripheral neuropathy symptoms and durable remissions in the subgroup of patients with R/R systemic ALCL, indicating that brentuximab vedotin monotherapy may be a potentially effective therapeutic option (Table 2).19

Discussion

The master protocol is a project tool designed to develop a clinical trial that can evaluate multiple research hypotheses and, most importantly, enhance the effectiveness of the clinical trial. The study above focused on one type of primary protocol, a basket trial, in which the efficacy and safety of targeted therapies are assessed in cancer patients with a specific molecular target, regardless of the tumor’s primary origin. In addition to identifying therapeutic options, precision oncology tracks tumor response to intervention at the molecular level and detects drug resistance and the mechanisms underlying its development.20, 21, 22

The USA, France, and the UK are the countries where the largest number of basket trials in oncology are conducted, reflecting the global trend in new research initiatives. The USA leads in the total number of clinical trials globally, while France is the leader in Europe. The fact that these trials typically involve 3 or more countries (on average) underscores the global nature of oncology research and the international collaboration required to address complex, rare and diverse cancer types. Most basket studies are early-phase I/II trials, highlighting that master protocol models are still relatively new concepts in clinical research. Pharmaceutical companies aim to expand the scope of implementing a single project across multiple therapeutic areas while reducing the costs of conducting clinical trials through master protocol research models.

The basket studies included in the systematic review primarily focus on solid cancers. Ongoing studies have defined “baskets” specific to particular molecular targets, aiming to determine the effectiveness of drugs acting on specific molecular pathways, including those used to treat other diseases. A basket study, which incorporates multiple independent, two-stage designs (1 per basket), is characterized by a higher false-positive rate compared to a typical phase II trial (i.e., there is a greater chance that a drug will be found effective in at least one basket, even if it is actually ineffective). The ability of basket trials to identify molecular subtypes across different solid tumors is particularly valuable, as demonstrated by the various targeted therapies evaluated in the reviewed trials, including those aimed at HER2 amplification, PD-L1 expression and MAPK/ERK pathway activation.

The success of such trials is exemplified by studies like KEYNOTE-158, which investigated pembrolizumab for advanced cervical cancer. The results of this trial led to FDA approval, underscoring the basket trial model’s potential to quickly translate genomic discoveries into clinical applications. Similarly, the study on pertuzumab and trastuzumab for HER2-positive cancers further highlights the importance of targeting specific molecular aberrations, regardless of tumor site.

Another significant finding was the inclusion of rare and pediatric cancers in the basket trial model. These populations, which often have limited treatment options due to small patient numbers and heterogeneous genetic profiles, stand to benefit from the precision medicine approach offered by basket trials. For example, the NCT03363217 study evaluating trametinib in pediatric glioma and plexiform neurofibroma highlights how basket trials can address the unmet need for effective therapies in younger populations with rare tumor types.

Basket trials have become a prominent approach in oncology, providing a valuable opportunity for patients who do not respond to standard anticancer therapies. The focus on molecular drug delivery targets differs from the traditional approach, which centers on the location of the primary tumor. The concept of molecular tumor profiling will enable cancer patients with specific molecular pathway alterations, regardless of tumor histology, to benefit from modern targeted therapies or immunotherapies. The growing trend of basket trials in oncology is promising, but further refinement in trial methodology, patient selection and biomarker-driven therapeutic development is essential to fully realize their potential.

For basket trials to be more effectively implemented in clinical practice, advancements are needed in patient selection, regulatory frameworks, data sharing, statistical analysis, and patient education. By improving access to diagnostics, fostering collaboration across disciplines and refining methodologies, basket trials can enable more targeted, personalized treatments across a wide range of diseases. With these improvements, basket trials have the potential to revolutionize clinical practice and reshape the broader landscape of precision medicine23.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The systematic review included only clinical trials from recent decades, and the articles were searched exclusively in English. Additionally, some basket clinical trials may not have been registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database.

Conclusions

The systematic review confirms that basket trials have significant potential as a clinical trial model, as evidenced by the increasing number of basket trial projects being conducted. Their effective use could lead to a deeper understanding of the pathogenesis of cancer, better assessment of therapy effectiveness, and more personalized patient care. These trials have shown considerable promise in improving outcomes across a variety of cancer types, from common solid tumors to rare cancers and pediatric malignancies. However, for basket trials to reach their full potential, continuous efforts are needed to refine trial designs, standardize methodologies, and ensure broad global participation. With the ongoing expansion of molecular profiling and targeted therapies, basket trials are poised to play an increasingly crucial role in the future of cancer treatment. Further methodological refinements and global collaboration are essential to fully realize the potential of basket trials in advancing personalized cancer care.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

During the preparation of this work the authors used OpenAI – ChatGPT in order to improve the language and readability of their paper. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.