Abstract

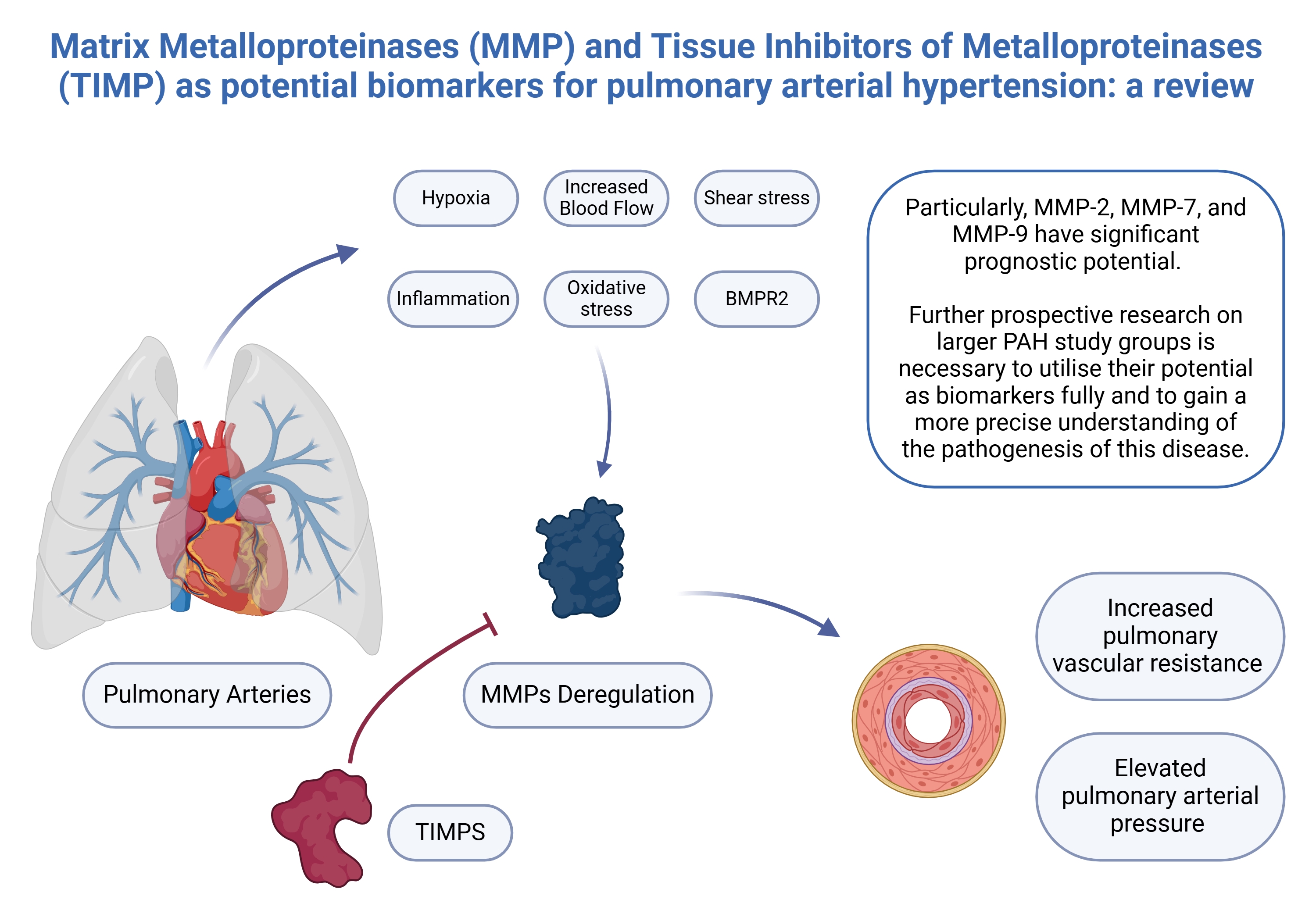

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare and progressive syndrome that is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage due to the nonspecific nature of its symptoms. Current research aims to identify novel diagnostic tools, including biomarkers, to facilitate earlier detection and differentiation of pulmonary hypertension (PH) subtypes. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play a critical role in the pathogenesis of PAH through extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, with their activity tightly regulated by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). This review summarizes existing studies on the potential of MMPs and TIMPs as biomarkers for PAH. Our analysis highlights significant differences in MMP concentrations between PAH patients and healthy controls. In particular, MMP-2, MMP-7 and MMP-9 exhibit promising prognostic value, which could contribute to risk stratification and support clinical decision-making in the future. However, large-scale, randomized prospective studies involving well-characterized patient cohorts are necessary to confirm their clinical utility and clarify their mechanistic roles in PAH pathogenesis.

Key words: prognosis, biomarkers, pulmonary hypertension, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases, metalloproteinases

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disorder marked by dysregulated endothelial-derived vasoactive factors, chronic inflammation and structural remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature.1 These pathological changes ultimately contribute to right ventricular (RV) failure.2 Hemodynamically, PAH is defined by a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) >20 mm Hg, pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >2 Wood units and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP) ≤15 mm Hg, as determined by right heart catheterization (RHC).3, 4

Despite the growing number of available treatment options, the management of PAH remains a significant clinical challenge worldwide. Identifying novel biomarkers is essential for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and recognizing patient subgroups at higher risk of poor outcomes. Among the various molecular pathways implicated in PAH, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their endogenous inhibitors – tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) – represent a promising area of ongoing research. A deeper understanding of these molecules may offer valuable insights into disease pathogenesis and help guide the development of future therapeutic strategies.

Objectives

This review synthesizes current evidence on the role of MMPs and TIMPs in PAH, with a focus on their implications for pathophysiology and their utility as biomarkers of this disease.

Methodology

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using the PubMed and Scopus electronic databases from their inception through July 31, 2024. The search strategy incorporated Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, including “pulmonary arterial hypertension metalloproteinases” and “pulmonary arterial hypertension biomarkers.” A total of 3,231 potentially relevant articles were initially identified. All manuscripts were independently screened by 2 reviewers. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: 1) not relevant to the selected topic, 2) case reports, 3) non-English language publications, 4) duplicate records, 5) lack of full-text availability, 6) animal studies, and 7) pediatric studies. After applying these exclusion criteria, 22 manuscripts were deemed eligible for inclusion in the analysis.

Interplay between MMPs and TIMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases are a family of zinc-dependent endoproteases that play a central role in the degradation and remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) components.5, 6 Their activity is tightly regulated through several mechanisms, including modulation of gene expression,7 activation of proenzymes,8 inhibition by TIMPs,9 subcellular compartmentalization,10 and formation of protein complexes.11 Most MMPs are not constitutively expressed; rather, their transcription is induced in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1 (IL-1) and various growth factors.12, 13

Additionally, certain MMPs are stored in the granules of inflammatory cells, thereby restricting their enzymatic activity to specific microenvironments.14 Dysregulated MMP expression and activity have been implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases, particularly cardiovascular disorders.15, 16 These endoproteases are initially synthesized as pre-proMMPs; during translation, the signal peptide is cleaved to produce the latent proMMP form. In this inactive state, the cysteine residue within the propeptide maintains coordination with a Zn2+ ion at the catalytic site through the “cysteine switch” mechanism, thereby preventing enzymatic activity. Activation occurs when this switch is disrupted, typically via proteolytic cleavage by enzymes such as serine proteases, furin endopeptidases, plasmin, or other MMPs.13, 17

The expression and activity of MMPs are tightly regulated by TIMPs.18 The TIMPs are the principal endogenous inhibitors of the MMP family, exhibiting varying inhibitory efficacy against different MMPs, along with distinct patterns of tissue expression and regulatory control.19 This family comprises 4 members – TIMP-1 through TIMP-4.6, 14 Despite their relatively small size, TIMPs serve multiple biochemical and physiological functions, including inhibition of active MMPs, activation of proMMPs, promotion of cell proliferation, matrix binding, and regulation of angiogenesis and apoptosis.14, 20 The TIMPs are distributed across various cellular compartments: TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4 can localize to the cell surface; TIMP-3 is also found in the ECM; and TIMP-1, -2 and -4 can exist in soluble forms. This spatial diversity enables TIMPs to modulate a broad range of cellular signaling pathways.19

The TIMPs are composed of 2 adjacent domains, each stabilized by 3 intramolecular disulfide bonds. The N-terminal domain, referred to as the “inhibitory domain”, is primarily responsible for MMP inhibition, as it alone is sufficient to suppress MMP activity. The highly conserved core epitope within this domain – centered around the N-terminal strand and characterized by a “Cys-X-Cys” motif – forms the principal interaction site with the catalytic domain of MMPs. This binding involves coordination with the catalytic zinc ion at the MMP active site, effectively blocking the substrate-binding cleft.21, 22 In addition to TIMPs, other molecules, such as α2-macroglobulin and amyloid β precursor protein, have also been identified as inhibitors of MMP activity.23, 24

The balance between MMPs and TIMPs largely influences the ECM composition, which tightly regulates MMP activity.25 Published evidence suggests that MMPs may contribute to the pathophysiology of PAH.26, 27 The early pathological progression of PAH primarily involves endothelial cells (ECs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in the vascular wall, as well as pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs).28, 29 The PASMCs are critically involved in disease advancement.30 The pathological state of PASMCs is associated with PASMC phenotypic switching.28

Several mechanisms have been proposed as potential initiating events in PAH, including increased blood flow and shear stress, hypoxia, inflammation, oxidative stress, and altered bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 signaling. These factors lead to endothelial/mesenchymal transition, in which ECs adopt a mesenchymal phenotype and express gene profiles characteristic of SMCs.28, 31 In fact, phenotypic switching is an early vascular self-repair mechanism in response to stimulation.1 During this process, ECs lose their intercellular junctions and detach from the intimal monolayer. Subsequently, they migrate into the medial layer, where they undergo dedifferentiation into myofibroblast-like mesenchymal cells.25 These cells exhibit increased secretion of α-smooth muscle actin, collagen, vimentin, and MMPs, as well as serine elastases and lysyl oxidases, while simultaneously showing reduced expression of their endogenous inhibitors, including TIMPs.25, 31, 32 Myofibroblast-like cells contribute to ECM remodeling through enhanced collagen deposition and cross-linking.25

Oxidative stress, exacerbated by inflammation, has also been implicated in MMP dysregulation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in response to inflammation have been shown to increase MMP secretion while downregulating TIMP expression in SMCs, ECs and fibroblasts. Furthermore, pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate the recruitment and activation of macrophages and neutrophils, which subsequently secrete MMPs and serine elastases. The degradation products of collagen and elastin generated by heightened proteolytic activity exhibit pro-inflammatory properties, thereby sustaining inflammation through a positive feedback loop.25, 33

Notably, the upregulation of MMP-1 and MMP-9 has been observed, enhancing the migratory capacity of adventitial fibroblasts.34 Deregulation of MMPs has been implicated in multiple pathological processes, including ECs and SMCs migration, hyperplasia, adventitial fibroblast transdifferentiation, increased ECM turnover, and inflammatory cell recruitment. These changes collectively contribute to increased vascular stiffness, preceding abnormal pulmonary arterial pressure and elevated PVR.25 Additionally, ECM degradation products and growth factors further stimulate MMP secretion,25 exacerbating vascular remodeling in small to medium-sized pulmonary vessels, ultimately leading to RV hypertrophy and right-sided heart failure (HF).35

Due to the non-specificity of the symptoms, PAH is frequently diagnosed at a late stage.36 At present, the only routinely used clinical markers that correlate with myocardial stress and provide prognostic information are brain natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).3, 37 However, these are not specific to pulmonary hypertension (PH), as they can be elevated in other heart diseases, showing significant variability.3 Research is now focusing on identifying new diagnostic methods, including biomarkers that allow for prognosis, diagnosis and differentiation of PH subtypes.38 Among the compounds under investigation are MMPs and their inhibitors, which may potentially fulfil this role.

Metalloproteinases

Matrix metalloproteinase 1

Matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1), a collagenase-1, acts on various substrates, including collagen types I, II, III, VII, VIII, and X, as well as gelatin, aggrecan, casein, nidogen, serpins, versican, perlecan, proteoglycan link protein, and tenascin-C.26, 39 Its expression is stimulated by high glucose levels in cultured ECs and macrophages40 and by C-reactive protein (CRP).41 Pulmonary arterial hypertension is often associated with glucose metabolism disorders,42, 43 and increased concentrations of this molecule in the lungs of PAH patients,42 but unchanged circulating levels have been observed.44 Furthermore, inflammation has been implicated in the pathophysiology of PAH,33 including its role in pulmonary vascular remodeling,45 as reflected by elevated CRP levels in PAH patients.46

Functionally, MMP-1 has been shown to induce the expression of a subset of proangiogenic genes in human microvascular ECs.47 Furthermore, it enhances vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGF-2) expression and ECs proliferation via protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1)48 signaling, a mechanism that may also contribute to pulmonary arterial vasoconstriction.49

Elevated serum concentrations of MMP-1 have been demonstrated in PAH patients.27, 50 Additionally, when monocytes were isolated, M1-polarized macrophages from PAH patients, but not from healthy controls, exhibited significantly higher MMP-1 protein levels compared to M0 and M2-polarized macrophages. Immunohistochemical assessment of lung tissue from PAH patients showed notably increased MMP-1 immunoreactivity compared to control samples.27 However, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis has not revealed significant differences in MMP-1 transcript expression between cells obtained from lung tissue from patients with idiopathic PAH (IPAH) during lung transplantation and samples from lobectomy of patients with localized lung cancer.51 Similarly, no difference in MMP-1 expression has been observed between pulmonary arteries of IPAH patients and downsized non-tumorous, non-transplanted donor lungs used as controls.52

Matrix metalloproteinase 2

Matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2), a member of the gelatinase subfamily of MMPs, degrades a broad range of substrates, including collagen types I, IV, V, VII, X, XI, XIV, as well as gelatin, aggrecan, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, proteoglycan link protein, and versican.39, 53 This MMP directly affects various cellular functions by modulating the activity of biologically active molecules or interacting with cell surface receptors.54 It is secreted as an inactive proenzyme, which undergoes activation via membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP). This process is tightly regulated by TIMP-2 at the cell surface at the site where activation is required.55 Several alternative pathways for MT1-MMP-dependent of MMP-2 have been described, involving proteases such as neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, proteinase-3,56 and plasmin.57 In addition to these pathways, a TIMP-independent activation route has been described, mediated by MT1-MMP and claudin-5.58 Furthermore, the generation of ROS by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase, induced by mechanical stretch, increases MMP-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and pro-MMP-2 release.59

A significantly elevated concentration of MMP-2 has been demonstrated in patients with PAH compared to the control group of healthy volunteers.60 Comparable results were observed in individuals with PH, where 19 out of 36 individuals included in the analysis were diagnosed with IPAH or associated PAH (APAH).61 Plasma circulating levels of MMP-2 were substantially increased in PH patients compared to healthy controls.61 Remodeling biomarkers, including MMP-2, and NT-proBNP, did not show significant differences in concentration between patients with PAH and those with other forms of PH.61 A study investigating patients with PH, including IPAH, PAH associated with connective tissue disease (PAH-CTD), chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH), PH due to left heart disease (PH-LHD), and non-PH controls (individuals suspected of PH who underwent RHC and had a mPAP <25 mm Hg), demonstrated that mean plasma circulating levels of MMP-2 were significantly higher in PAH-CTD and PH-LHD patients compared to non-PH controls.62 Furthermore, in PH patients, MMP-2 concentrations exhibited a weak but statistically significant correlation with cardiac output, PAWP and 6-minute walking distance (6MWD). Next, patients with plasma MMP-2 levels in the 1st (below 176 ng/mL) and 2nd quartiles (176–206 ng/mL) had significantly better 5-year survival and time to clinical worsening (TTCW) than those in the 4th quartile (≥246 ng/mL).62 These findings were further confirmed by Arvidsson et al., who linked elevated serum MMP-2 concentrations to an unfavorable prognosis in PAH.63 Increased circulating MMP-2 levels at the time of diagnosis correlated with higher European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Respiratory Society (ERS) risk scores, as well as with mean right atrial pressure, NT-proBNP, and 6MWD, indicating worsening right heart function and reduced exercise capacity. MMP-2 was identified as a valuable negative prognostic marker.63

Moreover, Karamanian et al. presented a study based on plasma analyses in PAH patients and healthy volunteers, in which it was shown that MMP-2 circulating levels were elevated in the plasma of non-IPAH patients, but not in the plasma of IPAH patients.64

Studies were also conducted on pulmonary artery tissue from patients undergoing lung transplantation for IPAH and from patients treated by lobectomy for localized lung cancer, who served as controls. In cultured PASMCs derived from patients with IPAH, MMP-2 activity is elevated, attributable to both elevated total MMP-2 expression and a higher proportion of its active form. In situ zymography and immunolocalization showed that MMP-2 was associated with SMCs and elastic fibers. Furthermore, in the arteries of IPAH patients, pronounced gelatinolytic activity and MMP-2 immunostaining were observed along the internal elastic lamina, extending even to its disruption.51 In contrast, the latent MMP-2 levels in IPAH cells remained indistinguishable from those in control cells.51 Conversely, another study reported no significant variation in MMP-2 expression levels in the pulmonary arteries of IPAH patients.52

A notable observation in one study was the elevated concentration of circulating CD34+CD133+ bone marrow-derived proangiogenic precursors in the peripheral blood of IPAH patients compared to healthy controls, with levels correlating with PAP. However, resident endothelial progenitor levels in the pulmonary arteries of IPAH patients were comparable to those in the control group. Colony-forming units of ECs derived from CD34+CD133+ bone marrow precursors of IPAH patients exhibited increased MMP-2 secretion, a greater affinity for angiogenic tube formation, and a tendency to form disorganized cell clusters spontaneously.65

Notably, no significant differences in pro-MMP-2 content were found between PAH patients and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or CTEPH. Additionally, no correlation was observed between pro-MMP-2 levels and PH severity indices.66

Concerning patients with systemic sclerosis-associated PAH (PAH-SSc), MMP-2 concentrations were significantly higher compared to the group of systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients without elevated pulmonary pressure.67 Another study involving 35 SSc patients, of whom 12 had PAH, found that MMP-2 circulating levels were similar in SSc patients with or without PAH.68

Matrix metalloproteinase 3

Matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP-3), or stromelysin-1, is involved in the degradation of various ECM components, including matrix proteins, growth factors, proteases, surface receptors, and adhesion molecules. Notably, this metalloproteinase can activate various pro-MMPs, making the synthesis and activation of MMP-3 a fundamental initiating event in the MMP-mediated degradation process.26, 69

Cells derived from IPAH patients demonstrated a marked reduction in MMP-3 production compared to control cells obtained from lung tissue excised during lobectomy for localized lung cancer in 6 individuals. Additionally, immunostaining for MMP-3 was detected exclusively in the media of pulmonary arteries in the control group.51 These findings are further supported by another study,60 which reported significantly lower serum MMP-3 concentrations in PAH patients compared to other subgroups of PH: CTEPH, PH due to HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF-PH), PH due to HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF-PH), and HF without PH (HF-NON-PH).60

Matrix metalloproteinase 7

Matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP-7) belongs to the matrilysins, which lack a hemopexin domain and act on many cell surface molecules.26 It is responsible for the degradation of collagen types I, II, III, V, IV, and X, aggrecan, casein, elastin, enactin, laminin, and proteoglycan link protein.39 Matrix metalloproteinase 7 degrades recombinant and native soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1), leading to the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) from sequestration by sVEGFR-1. In vitro assays demonstrate that MMP-7 promotes VEGF-driven angiogenesis by degrading sVEGFR-1, which otherwise sequesters VEGF and inhibits its activity. Additionally, this metalloproteinase releases VEGF from sVEGFR-1 secreted by human ECs, providing a regulatory mechanism for VEGF bioavailability within the local endothelial microenvironment.70 Elevated concentrations of MMP-7 have been observed in comparison with healthy volunteers without RHC; however, these levels remain lower than those measured in other patient groups (CTEPH, HFpEF-PH, HFrEF-PH, and HF-NON-PH). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of plasma MMP-7 concentrations in PAH compared to other PH groups and HF-NON-PH showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.75, with a sensitivity of 58.7% and specificity of 83.3%.60 It is noteworthy that plasma levels of MMP-7 increase with age,71 and patients with PAH were generally the oldest among the assessed PH groups. Nevertheless, relatively lower concentrations of MMP-7 were noted compared to other disease groups.60 Arvidsson et al.60 further demonstrated that plasma MMP-7 can differentiate PAH from other causes of dyspnea, including HF with or without PH, as well as from healthy controls, suggesting its potential utility as a novel diagnostic biomarker.

Matrix metalloproteinase 8

Matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP-8), a neutrophil-derived collagenase-2, is critically involved in the degradation of ECM components, targeting collagen types I, II, III, V, VII, VIII, and X, as well as gelatin, aggrecan, laminin, and nidogen.39 It is one of the MMPs participating in stem/progenitor cell mobilization and recruitment in blood vessel formation and vascular remodeling.26 Additionally, MMP-8 counteracts pathological mechanobiological feedback by modifying matrix composition and disrupting integrin-β3/FAK and YAP/TAZ-dependent mechanical signaling in PASMCs.72

Dieffenbach et al. conducted a study involving a diverse group of patients, including those with IPAH and APAH, which they categorized into a combined group of patients with PAH, PH, and healthy volunteers. Their findings revealed that the mean plasma concentration of MMP-8 was 18 times higher in PAH patients compared to controls. Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining demonstrated increased MMP-8 expression in PASMCs and the pulmonary endothelium of PAH patients relative to the control group.72

Matrix metalloproteinase 9

Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), a gelatinase-B enzyme, is responsible for the degradation of collagen types IV, V, VII, X, and XIV, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen, proteoglycan link protein, and versican.39 Its secretion is stimulated by high glucose levels.40 Notably, a reduction in the number of NK cells has been observed in PAH lung tissue, accompanied by functional impairments and overexpression of MMP-9.73 Elevated circulating levels of MMP-9 have been detected in the plasma of individuals with PAH,60, 74 suggesting a potential role in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Furthermore, for IPAH, study results are inconsistent, showing both increased levels of MMP-964, 75 and unchanged concentrations.62 Moreover, no statistical correlation was found between plasma MMP-9 levels and hemodynamic parameters or 6MWD, and no statistically meaningful association with survival was detected.62

It is of particular relevance that MMP-9 may be produced by macrophages.76 Chi et al. examined monocytes isolated from PAH patients and healthy donors, differentiating them into M0, M1 or M2 macrophage phenotypes. After differentiation with macrophage colony-stimulating factor into macrophages (M0), MMP-9 mRNA expression was significantly upregulated in PAH patients compared to controls. Similarly, MMP-9 mRNA levels were elevated in M0 and M1 macrophages derived from PAH patients relative to their counterparts in the control group.27

In a subset of patients with PAH related to PAH-CTD and PAH associated with congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD), circulating levels of examined compounds, including MMP-9, were high and did not significantly differ from concentrations in patients with idiopathic, hereditary and anorexigenic PAH. These results suggest that elevated concentrations are markers of disease presence rather than markers of PAH etiology.74 Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with IPAH, PAH-SSc, and healthy controls identified MMP-9-related genes, which were further analyzed using RT-PCR. This analysis revealed a clinically significant upregulation of these genes in patients with mild PAH compared to healthy controls, whereas no differences were observed in those with severe PAH.77 Interestingly, circulating MMP-9 concentrations were found to be higher in SSc patients without PAH than in those with PAH involvement.68 Vascular remodeling in CHD-associated APAH and IPAH, as well as in donor lung tissue, was analyzed for mRNA and protein expression patterns. Changes in vascular tissue demonstrated increased mRNA levels of MMP-9 in comparison with adjacent remodeled pulmonary arteries. While plexiform lesions in IPAH and APAH demonstrated only minor differences in remodeling-associated gene regulation, MMP-9 expression was upregulated in APAH compared to adjacent arteries, with a similar but statistically nonsignificant trend observed in IPAH. Importantly, hemodynamic parameters, including mPAP and PVR values measured prior to lung transplantation, had no effect on remodeling-associated gene expression in plexiform lesions.78

Pro-MMP-9 levels in circulating monocytes were found to correlate with key indices of severity of PH-induced cardiac failure but not with PVR or mPAP, suggesting a link between the pro-MMP-9 content of circulating monocytes and HF rather than pulmonary artery remodeling. Subgroup analysis further demonstrated that pro-MMP-9 was lower in patients with HF, defined by a right atrial pressure (Pra) >8 mm Hg and a cardiac index (CI) <2.5 L/min/m2, than in patients without HF.66

Matrix metalloproteinase 10

Matrix metalloproteinase 10 (MMP-10), a stromelysin-2 enzyme, acts on various substrates, including collagen types III, IV, V, gelatin, fibronectin, laminin, nidogen,39 and participates in pro-MMPs proteolysis.26 Increased serum concentrations of MMP-10 have been observed in PAH patients compared to healthy controls, with strong expression detected in the media and adventitia of human pulmonary arteries.27 Notably, MMP-10 expression was significantly reduced in the intima and media, as well as in perivascular tissue, of pulmonary arteries from IPAH patients. To explore the potential prognostic significance of regulated collagens and collagen-processing enzymes, circulating levels of MMP-10 were compared between donors and patients with IPAH. Both groups showed similar concentrations of MMP-10.52

Matrix metalloproteinase 12

Matrix metalloproteinase 12 (MMP-12), a macrophage metalloelastase,39 is involved in macrophage infiltration during inflammation. By facilitating macrophage migration across basement membranes, this enzyme enables their recruitment to inflamed tissues, thereby amplifying and sustaining the inflammatory cascade.79 Notably, circulating MMP-12 concentrations were significantly elevated in patients with PAH compared to the control group.60

Matrix metalloproteinase 19

The catalytic domain of matrix metalloproteinase 19 (MMP-19) exhibits proteolytic activity against a broad spectrum of ECM components, including collagen type IV, laminin, nidogen, large tenascin-C isoform, fibronectin, gelatin type I in vitro. These findings suggest its potential involvement in ECM remodeling.13, 80 Matrix metalloproteinase 19 is inhibited by TIMP-3 and, to a lesser extent, TIMP-1. Its expression was significantly elevated only in the intima + media of IPAH vessels compared to donor vessels.52

Table 1 summarizes the studies discussed above regarding the potential utility of MMPs as biomarkers for PAH. The table includes the PAH subtype and the number of patients enrolled in each study.

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) have been shown to exhibit multiple functions in regulating biological processes such as cell growth, apoptosis and differentiation.81 Independent of its metalloproteinase inhibitory activity, it exerts these effects through the activation of p38, mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase.82 The inhibitor suppresses the activity of most MMPs.83 Furthermore, plasma TIMP-1 correlates with markers of left ventricular diastolic filling and serves as a potential noninvasive marker of fibrosis.84 Notably, its circulating concentrations increase with age and are higher in males, individuals who smoke and those with diabetes.85 While TIMPs exhibit limited specificity towards individual MMPs, TIMP-1 preferentially binds to MMP-9,86 and their levels indicate a positive correlation.87

Higher concentrations of circulating TIMP-1 have been reported in the blood of PAH patients compared to age- and sex-matched healthy controls.62, 74, 88 In a subset of patients with PAH-CTD and PAH-CHD, circulating levels of TIMP-1 were high but did not differ significantly from those in individuals with idiopathic, hereditary and anorexigenic PAH.74 In a study focusing on patients with limited systemic sclerosis (lSSc), increases in TIMP-1 were found compared to healthy controls. It is worth emphasizing that the concentration of this molecule was higher in lSSc patients with PAH (PAH-lSSc) compared to those without PAH, underscoring its relevance as a biomarker for PAH-lSSc.89

An imbalance between MMP and TIMP was identified in cultured PASMCs derived from patients with IPAH through increased expression of TIMP-1. Immunostaining for this compound was observed in pulmonary arteries obtained from both control individuals and patients with IPAH. Furthermore, the same study showed a reduction in MMP-3 expression. This imbalance between MMP-3 and TIMP-1 may be responsible for promoting ECM accumulation.51 Notably, a significant correlation was observed between TIMP-1 and PAWP as well as the 6MWD. TIMP-1 plasma concentrations also increased with the rising New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class. Moreover, patients with TIMP-1 plasma circulating levels above the median exhibited significantly lower 5-year survival and a higher risk of death compared to those with concentrations below the median. This molecule demonstrates prognostic potential in the described cohort.62 In opposition to previous results, MMP-2/TIMP-1 and MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratios did not correlate with hemodynamic or clinical parameters, such as mPAP, PAWP, CI, or PVR, in IPAH patients.90 Multianalyte profiling analysis revealed increased circulating TIMP-1 levels in both IPAH and non-IPAH patients compared to healthy controls. Variations in inhibitor concentrations were observed across patient subgroups, with the highest levels detected in IPAH patients.64 In contrast to the aforementioned studies, TIMP-1 expression was reduced in the intima and media of pulmonary artery profiles from IPAH patient lungs, and its blood levels did not differ significantly between PAH patients and healthy volunteers.52 In the intima+media of IPAH vessels, collagens (COL4A5, COL14A1 and COL18A1), MMP-19 and a disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM) 33 were higher expressed, whereas MMP-10, ADAM17, TIMP1, and TIMP3 were less abundant.

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2) is constitutively expressed in most tissues, but it is not inducible by growth factors.19 This inhibitor exhibits antiangiogenic and antiapoptotic activities.20 In addition to inhibiting most MMPs, it also suppresses a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 12 (ADAM12).91 A key function of TIMP-2 is its participation in the formation of the ternary complex responsible for proMMP-2 activation at the cell surface.92

In IPAH, no significant alterations in TIMP-2 expression were detected in cultured PASMCs; however, increased TIMP-2 transcript expression was observed in PASMCs from IPAH patients compared to controls.51 Moreover, no differences in TIMP-2 expression were found between the lung tissue of patients with IPAH and the control group.52 In a study focused on patients with lSSc, RT-PCR confirmed an increased expression of 9 genes, including TIMP-2, in PAH-lSSc patients. A significant difference in TIMP-2 expression was noted between the PAH-lSSc and lSSc without PAH samples, which persisted between these groups even after excluding patients with extensive pulmonary fibrosis or mildly elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. This suggests that these PAH biomarkers are not primarily caused by pulmonary fibrosis or HF.89

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP-3) is distinguished by its ability to bind directly to ECM proteins, potentially stabilizing MMP-TIMP complexes within the interstitial space.32 It has the broadest range of substrates, including MMPs,19, 93 as well as several ADAMs: ADAM-17 (TNF-α-converting enzyme),19 ADAM-10, ADAM-12,9 and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTSs): ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5.94 An increase in TIMP-3 levels and the quantity of this protein in lung tissue from patients with IPAH has been observed compared to normal lung tissue. The majority of MMP inhibitor expression in the lungs is likely attributable to SMCs of the bronchi and pulmonary artery, as well as adult pulmonary fibroblasts. TIMP-3 expression has also been documented in lung ECs, ECs from placental microvessels and umbilical veins, and non-adherent blood-derived cell lines.95 In contrast to these findings, significantly lower gene expression of the aforementioned inhibitor was reported in the perivascular tissue of IPAH patients.52 TIMP3 expression was significantly lower in perivascular tissue of IPAH patients.

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4 (TIMP-4) is the largest identified human MMP inhibitor96 and has been associated with inflammation in cardiovascular disease, suggesting its potential role as a systemic biomarker of vascular inflammatory activity. Beyond its ability to inhibit MMPs, TIMP-4 also suppresses ADAM28.97 Elevated circulating TIMP-4 levels have been observed in patients with increased pulmonary artery systolic pressure measurements on echocardiography among patients with SSc, where pulmonary artery systolic pressure is considered elevated if it reaches or exceeds 40 mm Hg.98

In healthy individuals, plasma TIMP-4 concentrations are not influenced by sex or age.60 Schumann et al. confirmed that plasma TIMP-4 concentrations were significantly elevated in PH patients compared with healthy age- and sex-matched volunteers. The remodeling biomarkers, including TIMP-4, were not statistically significantly different between PAH and other forms of PH.61 The concentration of the metalloproteinase inhibitor was significantly higher in patients with PAH compared to the control group.60 This contradicted findings by Tiede et al., where mean circulating levels of TIMP-4 in plasma were notably lower in patients with IPAH compared with non-PH controls and patients with PH-LHD.62 These discrepancies may be attributable to differences in study populations; the first cited included both IPAH and PAH-SSc patients. Additionally, TIMP-4 exhibited modest yet significant correlations with mPAP, PAWP, PVR, and 6MWD,62 and its elevated concentrations are associated with unfavorable prognosis in PAH.63 No differences in TIMP-4 expression were found in the pulmonary arteries between IPAH patients and the control group.52 Within a subgroup selected from the previously mentioned cohort,62 the MMP2/TIMP-4 ratio was assessed, which showed a notable correlation with mPAP, PVR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, while MMP9/TIMP-4 showed significant correlation with mPAP and eGFR. Moreover, MMP2/TIMP-4 demonstrated considerable results in the ROC analysis predicting death and cardiovascular events.90

ADAM, ADAMTS and ADAMTSL

The equilibrium between ECM degradation and remodeling is regulated not only by MMPs but also by a disintegrin and metalloproteinases (ADAMs) and ADAMTSs,92 which are proteases closely related to MMPs.99 These molecules carry MMP and disintegrin-like domains, giving them the properties of both proteases and adhesion molecules.100, 101 Crucially, they can also be inhibited by TIMPs.14 ADAMTS8 has been implicated in PAH pathogenesis and RV failure, along with the expansion of PASMCs, ECM remodeling and endothelial dysfunction in an autocrine/paracrine manner.102

In a cohort of patients with IPAH, no significant differences in ADAMTS1 and ADAMTS13 expression were observed when compared to healthy volunteers.52 Upregulation of ADAMTS8 has been demonstrated in areas of α-smooth muscle actin, along with increased levels of this compound in the lungs of patients with PAH. Furthermore, RT-PCR has shown that the ADAMTS8 gene is more strongly expressed in PASMCs from PAH patients (PAH-PASMCs) than in control PASMCs. Notably, no significant difference in the expression of this protease was observed between control pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) and those from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH-PAEC). Moreover, the expression levels were comparable in both PAH-PAEC and PAH-PASMCs.102 These findings indicate that ADAMTS8 upregulation in PASMCs may contribute to the pathogenesis of PAH through PASMCs proliferation and migration, increased MMP activity and mitochondrial dysfunction.103

In patients with IPAH, no differences in ADAMTS13 expression were found compared to healthy controls, although the pulmonary embolism group exhibited slightly lower concentrations. Additionally, there was no correlation with sex or ethnic identity.104 Plasma samples from patients with incidentally diagnosed untreated PAH, as well as those with CTEPH, HFpEF, and a control population with dyspnea or HF without PH (dyspnea/HF-non-PH), were analyzed, alongside samples from 20 healthy controls. In contrast to previous reports, ADAMTS13 concentrations were significantly lower in PAH patients compared to individuals with CTEPH, HFpEF-PH, HFrEF-PH, dyspnea/HF-non-PH, and healthy controls. No differences were observed between subgroups analyzing IPAH and SSc-PAH. Furthermore, a correlation between ADAMTS13 levels and PAWP was established. The study concluded that using a multifactorial logistic regression model, incorporating age- and sex-adjusted ADAMTS13 concentrations, effectively differentiated PAH patients from other dyspnea-related disease groups, achieving AUC of 0.91, with a sensitivity of 87.5% and specificity of 78.4%.105

In a study on ADAMTSL4, Li et al.106 confirmed that plasma ADAMTSL4 protein concentrations were significantly elevated in patients with IPAH and CTEPH compared to healthy controls. It is noteworthy that the AUC for ADAMTSL4 was 0.947 for the PH group (IPAH and CTEPH combined) and 0.981 for the IPAH subgroup. Furthermore, plasma ADAMTSL4 concentrations exhibited a positive correlation with mPAP.

ADAM-10 and ADAM-17 play a critical role in the inflammatory response by promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, from peripheral blood macrophages and ECs.107 ADAM33 is involved in promoting angiogenesis, as well as stimulating cell proliferation and differentiation.108 No changes in ADAM10 expression were found in the media or intima of pulmonary arteries in patients with IPAH, but a significant reduction in expression of ADAM17 and upregulation of ADAM33 was observed.52 Additionally, plasma ADAM33 concentrations remained unchanged in IPAH patients compared to controls.52

Table 2 provides a summary of the studies examining the potential role of TIMPs as biomarkers in PAH. It outlines the PAH subtype investigated and the corresponding number of patients included in each study.

Discussion

The described compounds offer promising possibilities for more advanced diagnosis and for assessing prognosis in this challenging condition. Metalloproteinases exert a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of PAH through ECM remodeling. The concentrations of specific MMPs differ significantly between PAH patients and healthy individuals. Particularly, MMP-2, MMP-7 and MMP-9 exhibit considerable prognostic potential, which may help in clinical decisions in the future. Furthermore, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2, when assessed in conjunction with a panel of 7 additional circulating proteins, have been shown to effectively identify PAH patients at high risk of mortality.109 A potential biomarker, it can refer not only to the concentration of a particular molecule but also to their proportion to one another, for instance, MMP-2/TIMP-4 and MMP-9/TIMP-4, which correlate with clinical outcomes. In addition, manuscripts have shown differences in biomarker concentrations between PAH and other causes of PH. These findings, along with comparisons of biomarker concentrations between PAH and other causes of PH, have been drawn from Table 1 and Table 2, which summarize and contrast the referenced studies. Notably, the small sample sizes in many studies, an inherent limitation given the rarity of PAH, present challenges in formulating clinically valid conclusions. Furthermore, a significant proportion of investigations have relied on lung tissue samples, restricting the practical application of potential biomarkers due to the invasive nature of tissue sampling. Future research should prioritize less-invasive biomarkers to facilitate broader clinical implementation.

Phenotypic switching, which plays a unique and pivotal role in the initiation of PAH, is considered a critical early marker of pulmonary vascular remodeling and disease progression.28 Identifying biomarkers capable of capturing the onset of PAH could enable risk stratification and facilitate earlier therapeutic intervention. Emerging therapies, such as sotatercept, have been shown to improve quality of life and potentially extend survival in patients with PAH. A delay of 2 years in initiating sotatercept therapy could result in a loss of 4.1 life years per patient,110 underscoring the essential requirement for early diagnosis and treatment initiation.

Advancements in the understanding of MMPs and their inhibitors have contributed to the identification of novel therapeutic targets for PAH. Lercanidipine, a vasoselective dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, has demonstrated potential clinical benefits in PAH by reducing serum MMP-9 levels and improving survival without affecting proMMP-2 activity or TIMP-1 levels.111 Meanwhile, the endogenous elastase inhibitor – elafin – has been postulated to exert protective effects against PAH by suppressing MMP-9 activity. Experimental models of PAH have consistently shown increased elastase activity, and elafin is now progressing through clinical evaluation, with initial trials assessing its safety and tolerability in healthy volunteers.112

Limitations

Our analysis was limited to 2 databases, which may have restricted the number of studies identified. However, PubMed and Scopus are the 2 largest databases primarily focused on medical research, ensuring broad coverage of relevant literature. The screening process was conducted independently by 2 reviewers, who subsequently compared the included studies, thereby minimizing the risk of selection bias. All studies meeting the inclusion criteria were considered, which resulted in variability in sample sizes and PAH subtypes included. These differences were systematically presented in tables, allowing for a more objective comparison of the reported findings.

Conclusions

These findings highlight the pivotal role of MMP-related pathways in the pathophysiology of PAH and suggest that targeted modulation of these mechanisms may offer promising therapeutic avenues. However, to determine the clinical applicability of MMP-targeted therapies and their potential to alter disease progression, rigorous evaluation through prospective, controlled trials is essential. Large-scale studies are required to validate these initial observations, with particular emphasis on the standardization of biomarker measurement protocols – including sample collection, processing and analytical methods – to ensure reproducibility and comparability across research settings. As our understanding of PAH deepens, the integration of validated biomarker assessments into clinical practice may enhance patient outcomes through more precise, personalized therapeutic strategies.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technology

Not applicable.