Abstract

Background. Initiating orthodontic treatment before the pubertal peak results in more pronounced long-term craniofacial changes in the maxilla and adjacent structures. Dental malocclusion correction through maxillary expansion has been shown to significantly increase the patency and decrease the airflow resistance in several airway compartments, ranging from the nares to the epiglottis plane.

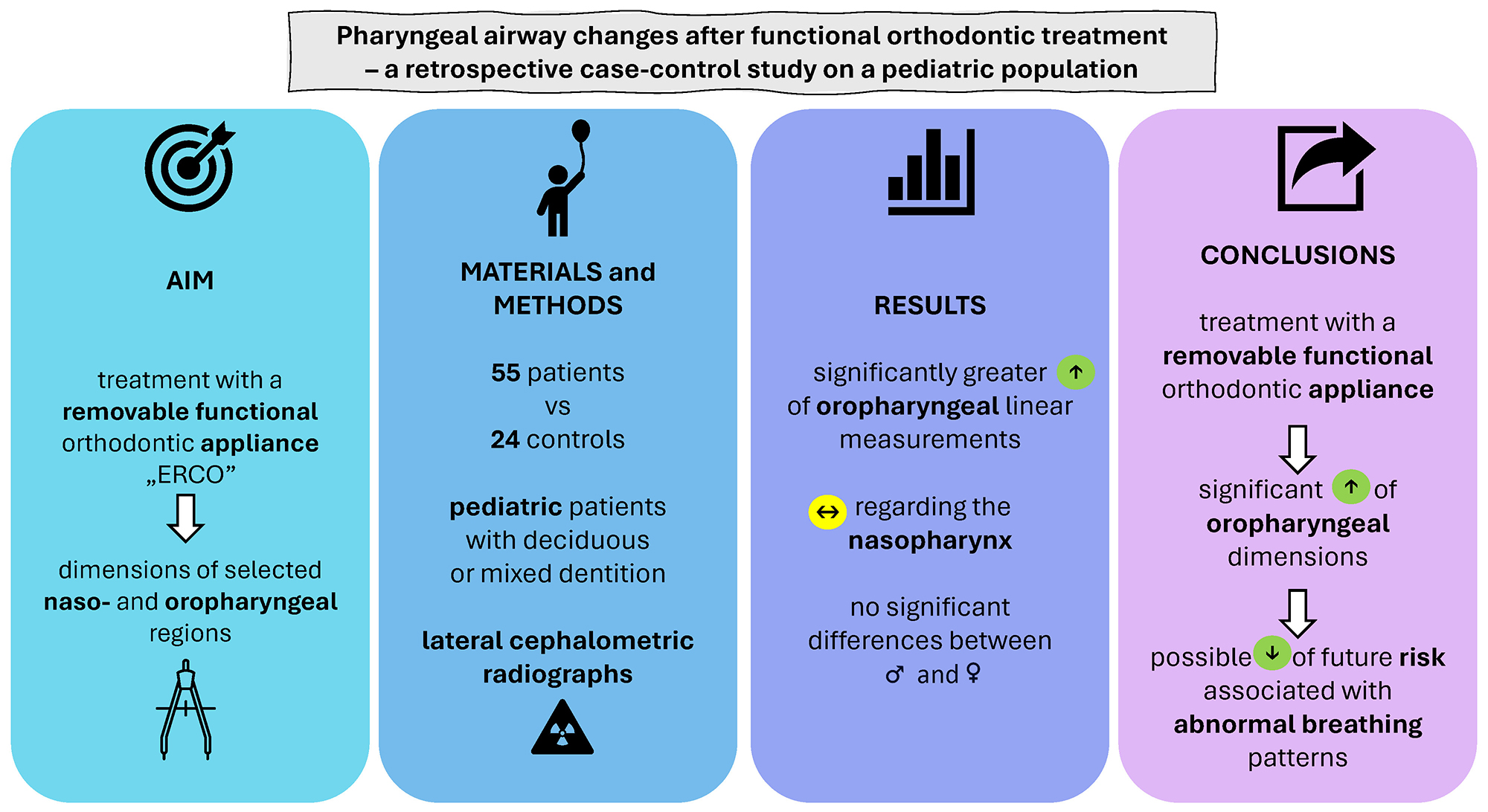

Objectives. We aimed to assess the impact of treatment with a removable functional orthodontic appliance on the dimensions of selected sections of the upper respiratory tract in pediatric patients, with the goal of identifying the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal regions most susceptible to lateral maxillary and mandibular expansion.

Materials and methods. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records and lateral cephalometric radiographs (LCRs) of all consecutive pediatric patients with deciduous or mixed dentition treated with a functional appliance between 2014 and 2019 at a private orthodontic practice in Racibórz, Poland. To assess the impact of the study group and gender on the dependent variables, a Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) was performed. The variable T1 (age at treatment initiation) was included as a covariate in the model to control for its potential effect on the outcomes.

Results. The treatment group comprised 55 patients, while 24 subjects served as the control group. In contrast to the nasopharyngeal variables, the average annual increase in the oropharyngeal linear measurements was significantly greater in the treatment group. For the gender factor, after applying the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, no statistically significant differences were observed in any of the assessed variables. In contrast, after correction, the covariate T1 was statistically significant for the following variables: CVM1 and CVM2 (skeletal age before treatment initiation and after treatment completion, respectively), and T2 (chronological age after treatment completion).

Conclusions. Although treatment with a removable functional appliance does not significantly impact the nasopharyngeal airspace, it significantly increases oropharyngeal dimensions, which may help reduce the future risk associated with abnormal breathing patterns in treated patients.

Key words: nasopharynx, cephalometric analysis, functional orthodontic treatment, oropharynx, malocclusion

Background

Upper airway obstruction, arising from allergic rhinitis, adenoid and tonsil hypertrophy, congenital nasal deformities, or polyps, has been outlined as a possible contributing factor to the development of dental malocclusion in adolescents.1, 2 Oral respiration pattern due to the nasal obstruction induces incorrect tongue positioning with the loss of its upward pressure on the palate, which hinders the proper development of the upper jaw, resulting in a narrower dental arch and subsequent teeth crowding.3, 4, 5

Long-term complications of not addressing maxillary and mandibular deficiencies at an early age include articulation disturbances, periodontal disorders, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, obstructive sleep apnea, and psychological sequelae associated with poor facial esthetics.6 Therefore, many transverse abnormalities require conservative maxillary orthopedic correction during the growth period.7 Interceptive orthodontic treatment, initiated during the deciduous or early mixed dentition phase,8 may reduce the complexity of future procedures or even prevent the need for more complicated and costly interventions.9

Although several orthodontic treatment modalities have been introduced for maxillary and mandibular deficiencies,10, 11 early extraction of deciduous teeth in an attempt to reduce or avoid future malocclusion has been shown to neither decrease the need for further orthodontic treatment nor reduce its complexity or duration.12 This has influenced the current trend toward more conservative, non-extraction management.13

Notably, the initiation of maxillary expansion before the pubertal peak results in significant long-term craniofacial changes at the skeletal level, both in the maxilla and adjacent structures, which are more pronounced than when intervention occurs during or slightly after the peak in skeletal growth.14 Furthermore, maxillary expansion has been shown to significantly increase the dimensions of various airway compartments, from the nares to the epiglottis plane, contributing to decreased respiratory airway resistance.13, 15, 16, 17, 18

Objectives

The purpose of our study was to assess the impact of treatment with a removable functional orthodontic appliance on the dimensions of selected sections of the upper respiratory tract in pediatric patients, with the goal of identifying the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal regions most susceptible to lateral maxillary and mandibular expansion.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to its retrospective nature, institutional approval from the Ethics Committee was waived. Informed consent was obtained from all enrolled participants and their parents. The paper was prepared following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.19

Subjects

The data were collected retrospectively from the medical and dental history records and lateral cephalometric radiographs (LCRs) of all consecutive pediatric patients diagnosed and/or treated with a functional orthodontic appliance between 2014 and 2019 at a private orthodontic practice in Racibórz, Poland. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) deciduous or mixed dentition, 2) presence of at least two teeth distally and mesially from the canines, and 3) adequate radiographic documentation (2 good quality LCRs performed in the period of deciduous and/or mixed dentition). The exclusion criteria comprised: 1) previous head and neck surgeries, 2) presence of congenital craniofacial defects or facial cleft, 3) history of chronic airway/pulmonary diseases (e.g., asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and 4) history of previous orthodontic treatment. The management plan included the treatment without extraction of permanent teeth in individuals with deciduous teeth without tremas (between incisors and upper canines, as well as canines and lower molars) and in patients with different forms of malocclusion in 3 planes with deciduous or mixed dentition. The treatment goal constituted lateral expansion and optimization of shape development of the dental arches, as well as normal and/or optimal alignment of the mandible to the maxilla during this developmental period. The patients were offered two-stage orthodontic treatment: 1) with the functional ERCO appliance created according to the disign of the first author (Z.P.) and 2) with thin-arch fixed orthodontic appliances, correcting the position of the teeth. Patients who completed the first stage of treatment with the ERCO appliance and, according to the patients and their parents, strictly adhered to the orthodontic recommendations (appliance worn 24 h a day except for meals and oral hygiene procedures) were enrolled in the treatment group. The control group included all consecutive patients who had not started treatment with the ERCO appliance after diagnosis and attended regular orthodontic checkups during the study period.

Functional orthodontic appliance

The orthodontic ERCO appliance (Figure 1) was created according to the design and treatment indications of the first author (Z.P.). The functional appliance was formed using a construction bite with a minimum vertical distance between the upper and lower dental arches (i.e., with the lack of contact of antagonistic teeth). In the sagittal dimension, occlusion was established by bringing upper and lower dental arches close to each other by a maximum of 1 premolar width. In the lateral position, the lower dental arch was placed so as to bring it closer to the mid-sagittal plane. The vertical zone separating the dental arches was filled with acrylic, which could be removed by the clinician. The appliance had 2 active elements, i.e., upper and lower screws, activated once a week. During treatment, the appliance was loosely fitted in the mouth.

Cephalometric analysis

All LCRs were taken using the same device (Vatech, Digital X-ray Imaging System; Voxel Dental Solutions, Houston, USA; PCH-2500, 85 kVp, 10 mA) under the same exposure conditions. Prior to imaging, patients were instructed to hold their heads in a natural position and look at their eyes in the mirror 250 cm away. Teeth were in central occlusion, while the lips and tongue were in the resting position. All subjects were instructed not to swallow saliva or move their heads during image acquisition. All LCRs were saved to a computer disk. The images were corrected for magnification, and a ruler with a scale was visible on the LCRs. The test measurement was performed using the ruler to ensure compatibility with the actual values. The measurements were scaled isotropically. Cephalometric measurements were obtained using DesignCAD software with the Orthodon-MPaluch program (Mateusz Paluch, Racibórz, Poland). The following cephalograms were analyzed: 1) the first diagnostic LCR taken before treatment in both the treatment and control groups, and 2) the second LCR taken after the last expander screw activation in the treatment group, and after the change in the treatment method prior to the insertion of the fixed appliance in the control group.

Figure 2 shows the main cephalometric landmarks used in the study. The definitions of the applied cephalometric landmarks and the variables they formed are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Some of the landmarks and the variables were defined by the first author (Z.P.) and marked as “zp”. In our experience, they can be used as a stable and reproducible alternative for already established points, which may not be clearly visible in many radiographs and might be affected by orthodontic teeth movements and bone remodeling in relation to growth20, 21. Landmarks were determined on all LCRs in the treatment and control groups. Subsequently, after 1 month, all landmarks were re-determined to eliminate intra-examiner variability. Craniofacial skeletal maturation was established according to the cervical vertebrae maturation (CVM) method.22, 23

Statistical analyses

To assess the impact of the study group (study vs. control) and gender (female vs. male) on the dependent variables, a Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) was conducted. The variable T1 (treatment initiation time) was included as a covariate in the model to control for its potential effect on the outcomes.

Before conducting the MANCOVA, the assumptions were verified. The normality of the dependent variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The homogeneity of covariance matrices was evaluated using Box’s M test, while the homogeneity of variances within groups was tested with Levene’s test.

If a significant MANCOVA effect was found, post-hoc ANCOVA tests were conducted for each dependent variable separately. The ANCOVA model included Group and Gender as factors and T1 as a covariate. Additionally, to control for the false discovery rate (FDR), the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was applied. The p-values were sorted in ascending order and adjusted using the formula:, where “n” was the total number of tests, and “rank” was the position of the p-value in the ordered set. The adjusted p-values were then compared to an alpha threshold of 0.05 to determine significance after correction.

Results

The analysis included data from 79 patients (51 men and 28 women): 55 individuals (mean age 8.23 ±1.71 years) constituted the treatment group, while 24 patients (mean age 7.97 ±1.86 years) formed the control group. Detailed group sizes are presented in Table 3. Since this retrospective study included complete data for all participants, statistical analysis was conducted based on 2 LCRs obtained for each individual.

Before conducting the MANCOVA analysis, the assumptions of this method were verified. The normality of the distribution of dependent variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The results indicated no significant deviations from normality for most variables. Given the general robustness of MANCOVA to violations of normality, the analysis was conducted without data transformation. The homogeneity of covariance matrices was assessed using Box’s M test, which yielded M = 85.47, F = 1.570, p = 0.002. The homogeneity of variances within groups was evaluated using Levene’s test, which indicated that the variances of 3 dependent variables differed significantly (p < 0.05). Consequently, Pillai’s trace was used as the primary MANCOVA test statistic instead of Wilks’ lambda.

The analysis revealed a significant effect of the experimental group (Group: treated vs control) on the dependent variables (Pillai’s trace = 0.625, F(df1, df2) = 3.329, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.625). The results of the between-subjects effects tests (Table 4) indicated that, before the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, significant differences between groups were observed for 6 variables: middle pharyngeal wall (MPW), corresponding to the retropalatal airspace, the posterior length of the entire pharynx (Pal2), the length of the pharynx (VAL), oropharynx (zp), the dimension of the pharyngeal airspace (PNS-UPW), and the anterior length of the entire pharynx (Pal1).

After applying the false discovery rate (FDR) correction, statistical significance was retained for only 3 variables: MPW (p_adj = 0.009, η2 = 0.117), Pal2 (p_adj = 0.007, η2 = 0.138), and VAL (p_adj < 0.001, η2 = 0.154). For the gender factor, significant differences were observed before correction for the variables CVM and middle airway space (MAS), but after correction, no variables remained significant. The group × gender interaction was not significant for any dependent variable. The covariate T1 (age at treatment initiation) was statistically significant for the following variables: skeletal age before treatment initiation (CVM1), skeletal age after treatment completion (CVM2), nasopharynx (zp), the distance between the posterior nasal spine and the midpoint of the sella turcica (PNS-S), and chronological age after treatment completion (T2). However, after applying the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, significance remained only for 3 variables: CVM1, CVM2, and T2. The results of the post-hoc ANCOVA with Benjamini–Hochberg correction are presented in Table 5. Box-and-whiskers plots illustrating the results are presented in Figure 3, Figure 4.

Discussion

Oropharyngeal measurements

In the present study, the analysis of changes in upper airway variables on LCRs (taken in the sagittal plane) was conducted in patients where the primary therapeutic forces, due to the presence of 2 screws in the orthodontic appliance, were directed laterally, perpendicular to the sagittal plane. Notably, the MPW values increased significantly more in the treatment group, despite the main expansion forces acting in a plane different from the measurement direction. Our study results align with those presented in the report by Özbek et al., where, however, the forces used in the appliance acted in the anteroposterior direction, thus aligning with the plane of the LCRs.24 In turn, Ulusoy et al. reported that although a statistically significant increase in the oropharyngeal area was observed in the treatment group during the retention period (after the active treatment phase with an appliance involving anteroposterior and vertical activation), the overall changes in the horizontal oropharyngeal measurements and the surface area of the oropharynx on LCRs did not differ significantly between the analyzed groups. These findings are in line with our observations.25

Among patients with sleep-disordered breathing, a retrognathic position of the mandible in relation to the cranial base is often observed, which predisposes to the narrowing of the pharyngeal airway passage.26, 27, 28 The posteriorly positioned tongue and soft palate, which reduce the pharyngeal dimensions early in life, may contribute to subsequent impaired respiratory function, snoring, upper airway resistance syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea.26, 27, 29 Concurrent soft tissue changes, attributable to age, obesity, and genetic background, further reduce the oropharyngeal airway.27 The observed MPW increase following treatment (reflecting the enlargement of the oropharynx depth)26, 27 might be attributed to the mandibular advancement caused by the functional appliances, influencing the position of the hyoid bone and, consequently, leading to the forward relocation of the tongue.26, 27 Since changes in pharyngeal dimensions following functional appliance therapy have been reported to be maintained in the long term, such management may help prevent adaptive changes in the upper airway, thereby potentially influencing the risk of obstructive sleep apnea development later in life.26, 30, 31

Before the functional treatment in patients with mandibular retrognathism, the backward position of the tongue tends to press the soft palate, which leads to a decrease in its thickness, with a concurrent increase in its length and inclination.26, 27 Despite the lack of statistically significant differences in soft palate thickness between the treatment and control groups, we observed a lower average annual increase in soft palate length after expansion treatment. In contrast, Ghodke et al. found a tendency toward improvements in soft palate length, thickness, and inclination after mandibular retrusion correction, with the change in inclination reaching statistical significance.26 Similarly, Jena et al. observed significant improvements in the adaptation of the soft palate (i.e., an increase in its thickness with a concurrent decrease in its length and inclination) following the treatment of Class II malocclusion using functional appliances. After treatment with a twin-block appliance, the soft palate measurements were found to align with the values seen in healthy controls.27 Therefore, the positive impact of functional treatment on airway dimensions cannot be attributed solely to the induced skeletal changes but also to the increased genioglossal muscle tone and soft tissue adaptations resulting from the forward positioning of the mandible during treatment.27, 30

Nasopharyngeal measurements

Contrary to the oropharyngeal variables, we observed that the linear measurements and the surface area of the nasopharynx did not differ significantly between the treatment group and the controls. Similarly, several authors have reported no significant differences in nasopharyngeal measurements when compared with the control group in both the short and long term, despite the favorable alterations in the nasopharyngeal area induced by functional treatment.25 Therefore, it has been postulated that the growth of the nasopharynx occurs independently of functional appliance treatment, and that nasopharyngeal dimensions may not be influenced by mandibular-sagittal changes but rather by sphenoid wing expansion and the forward sliding of the palate.27, 32 Furthermore, the lack of significant differences was found to be partially attributed to the age of patients at the initiation of functional treatment (beginning of pubertal growth), and thus, no expected alterations in airway size related to the growth process were observed, as the airway capacity was already adequate.25 Additionally, it has been hypothesized that a more pronounced advancement in airway dimensions could have been observed in patients with retrognathic facial structures or breathing-related sleep disorders, due to their more significant intrinsic stimulus to increase airway capacity.25 Moreover, the values of the nasopharyngeal measurements on LCRs may be associated with the physiological development pattern of the adenoid tissue, which continues to grow until puberty, followed by a gradual decline.25, 33

Limitations

The study’s limitations include its retrospective design and the use of conventional LCRs in the evaluation of airway spaces, which precluded a detailed multiplanar analysis of the dentomaxillofacial complex. Nevertheless, LCRs are still routinely used in orthodontic practice and, in most conservative treatment cases, serve as a sufficient tool for monitoring growth and conducting accurate treatment progress assessments.24, 25, 26, 27 Since a positive correlation between linear naso- and oropharyngeal cephalometric measurements and the corresponding pharyngeal volume in cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) exams has been described, it becomes even more critical to strictly adhere to the directive of limiting radiation exposure in pediatric patients to the greatest extent possible and to fully justify the acquisition of CBCT scans in routine orthodontic practice.34, 35, 36, 37, 38

Furthermore, in our study, the division of the treatment and control groups according to skeletal classifications (regarding the anteroposterior relationship between the maxilla and mandible) was not implemented. Mislik et al. found only a few weak correlations between the “p” distance (the shortest distance between the soft palate and the posterior pharyngeal wall) and the “t” distance (the shortest distance between the tongue and the posterior pharyngeal wall) to various cephalometric landmarks with no significant correlations to the angle of the mandible or skeletal class.39 Additionally, Alves et al. reported no significant correlations between the ANB (the cephalometric parameter of choice for assessing the anteroposterior relationship between the maxilla and mandible) angle (formed between the most concave point of the anterior maxilla, nasion, and the most concave point on mandibular symphysis) and pharyngeal linear and surface measurements.40 Nevertheless, since discrepancies in pharyngeal airway dimensions depending on the mandibular position have been observed, the implementation of skeletal classifications might have been valuable in interpreting the results.41

Moreover, the study’s retrospective nature precluded the analysis of confounding factors (such as initial malocclusion severity and patient compliance) on the functional treatment outcomes. Additionally, the presented results should be interpreted with caution due to the lack of long-term follow-up data, which would help define the ultimate sequelae following treatment with the ERCO appliance. Future studies evaluating larger patient cohorts, including those treated during the early permanent dentition phase, and with a more extended follow-up period (e.g., during the retention phase after the active treatment phase) are highly warranted.

Conclusions

Expansive treatment using a removable functional appliance in children during the deciduous or mixed dentition phase does not significantly impact nasopharyngeal airspace dimensions. In contrast, lateral expansion of the maxilla and mandible with the functional appliance significantly increases the oropharyngeal airspace dimensions in the sagittal plane, which may reduce the future risk associated with abnormal breathing patterns in these patients.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are openly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15126951. The package includes the following files:

Consent for publication

Not applicable

.jpg)

.jpg)

-pion.jpg)

-pion.jpg)