Abstract

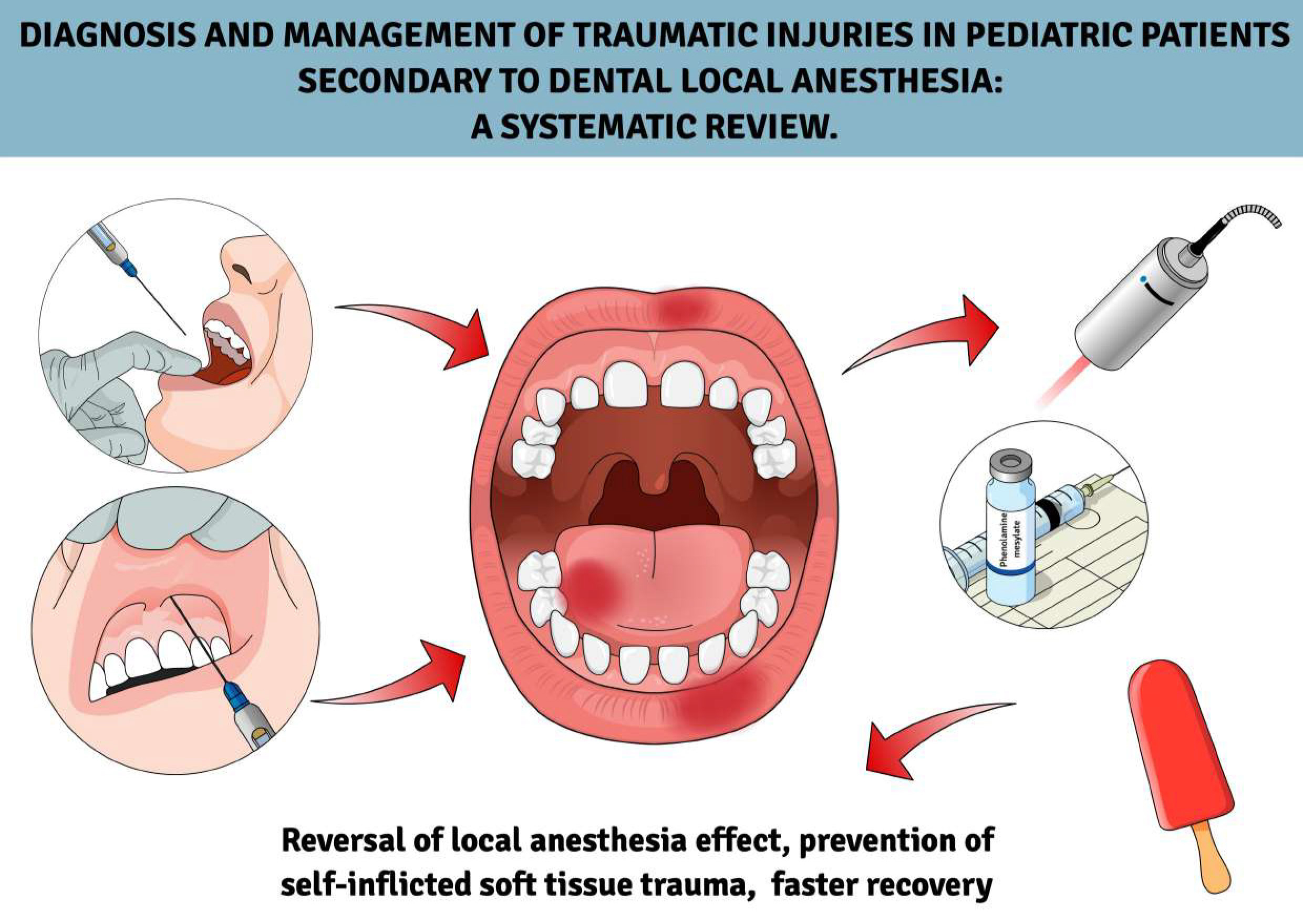

This study examines soft tissue injuries secondary to the prevalence of local anesthesia, differential diagnosis and therapeutic approaches.

In October 2024, a comprehensive search was performed in PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus along with gray literature sources, adhering to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, using the following keywords: “bite”, “traumatic injuries”, “soft tissue injuries”, “self-inflicted injuries”, “topical anesthesia”, “local anesthesia”, “pediatric”, or “children”. The search was limited to English-language publications. Additional manual screening of reference lists was performed. The risk of bias was assessed using the checklist developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI).

Out of 574 identified studies, 21 were included in the qualitative analysis (9 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 6 case reports and 6 cohort studies), mainly focusing on children aged 6–12. Anesthesia methods included traditional techniques (12 studies) and computer-controlled injection (5 studies). The role of articaine (9) and lidocaine (10) was analyzed. Suggested interventions to mitigate injury risks and improve recovery included the use of phentolamine mesylate (2 studies) and non-pharmacological strategies: intraoral appliances (2 studies) and photobiomodulation (2 studies). The included studies varied in design, sample size and duration, limiting direct comparisons. Effect sizes and confidence intervals were inconsistently reported, and the risk of bias assessment using the Cohen’s kappa test highlighted methodological heterogeneity and potential reporting bias.

Soft tissue injuries from local anesthesia in children can cause significant pain and cooperation issues. Effective strategies include early intervention with pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Increased awareness and patient-specific management are essential for reducing risks and improving outcomes.

Key words: children, local anesthesia, soft tissue injuries, anesthesia

Introduction

Lesions secondary to local anesthesia in children are rare but may occur as the child’s response to the procedure. These lesions are typically related to the local anesthetic agent used by the technique. However, they are mainly the result of inappropriate behavior of the child due to prolonged numbness after administration of local anesthesia.1, 2 After the procedure, when stress levels have subsided and the child is still under anesthesia, they may be unfamiliar with the sensation of numbness. As a result, they might bite or chew on their lips, cheeks or tongue, potentially causing painful injuries.1 Timely diagnosis and appropriate management help minimize complications and promote healing of soft tissue injuries caused by local anesthesia.

Regular follow-up is crucial to monitor recovery and prevent complications.2 If the lesion does not resolve or worsens, it is recommended to seek the help of a pediatric dentist, oral surgeon or appropriate specialist. All cases with severe or non-healing ulcers should be indicated when considering malignancies or systemic causes such as autoimmune diseases, as well as complicated infections requiring surgical drainage or hospitalization.3 If the lesions recur or appear in different areas, neuropathy should be considered, as this may indicate persistent sensory disturbances or underlying nerve damage.4 These injuries are usually preventable with careful planning of the time needed for anesthesia for the procedure, a precise technique of anesthetic administration, considering the use of local anesthetic reversal agents such as phentolamine mesylate, and careful post-procedure education of healthcare professionals to monitor the child.5, 6

To effectively address this often misdiagnosed condition, a thorough understanding of proper diagnostic techniques is essential.7, 8 The differential diagnosis of soft tissue injury should consider trauma during anesthesia delivery, which may present as redness, swelling or ulceration caused by mechanical or physical damage during injection.7, 9 Rare allergic reactions to local anesthesia may manifest as itching, swelling or rash, while infection may present with localized pain, warmth, erythema, or systemic symptoms.9 Chemical or thermal burns resulting from exposure to caustics or excessive heat should also be assessed. Injection site complications, such as localized hematoma, edema or necrosis caused by improper injection technique, can lead to swelling or discoloration. In addition, neuropathy resulting from temporary or permanent nerve injury can cause symptoms such as paresthesia (tingling or numbness) or dysesthesia (abnormal, often painful sensations). Accurate identification of these potential causes is essential for effective management and the prevention of complications.9, 10

Although often self-limiting, traumatic soft tissue injuries following local anesthesia in children can lead to complications such as ulceration, secondary infection or neuropathic pain, highlighting the importance of early recognition and management. Despite their clinical significance, research on these injuries remains fragmented, with most studies limited to case reports or small-scale observations rather than comprehensive evidence-based assessments. There is a lack of high-quality evidence on effective prevention and management strategies, and inconsistencies in age-specific clinical approaches further complicate decision-making. Given these gaps, a systematic review is needed to consolidate existing knowledge, evaluate diagnostic and preventive strategies – such as anesthetic reversal agents and post-procedural education – and assess treatment effectiveness, ultimately guiding standardized, evidence-based clinical practices.

Objectives

There is no current published literature review on soft tissue injuries resulting from local anesthesia in children. While most complications occur immediately, late-onset issues can affect essential functions like eating, speaking and chewing, particularly in young children and those with behavioral challenges. These complications may cause pain and impact future dental cooperation. This review aims to synthesize existing research, provide insights into prevalence, diagnosis and management strategies, and raise clinical awareness to improve patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Focused question

This systematic review was conducted using the PICO framework to address the following clinical question: In children undergoing local anesthesia (Population), how does the diagnosis of traumatic injuries related to anesthesia (Intervention) and the strategies for their management (Comparison) influence the reduction of postoperative trauma (Outcome) compared to no specific intervention or standard care?11

Protocol

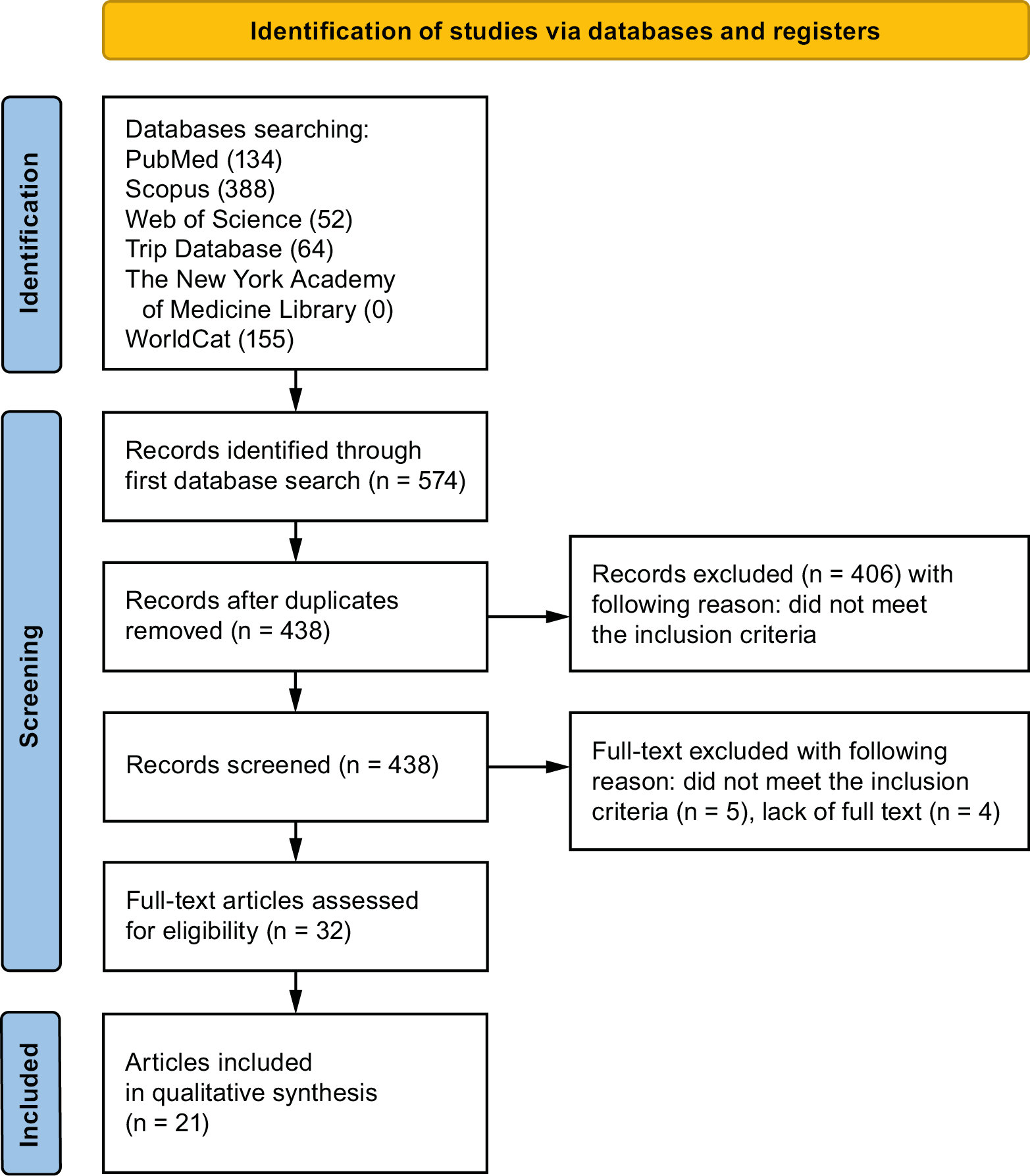

The process of selecting articles in the systematic review was carefully outlined following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart (Figure 1).12 The systematic review was registered on the Open Science Framework at the following link: https://osf.io/4xwdz (accessed December 9, 2024).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were considered acceptable for inclusion in the review if they met the following criteria12:

– children up to 18 years old;

– use of local anesthesia;

– observation of soft tissue trauma in a few postoperative days;

– clinical cases;

– studies in English;

– prospective case series;

– non-randomized controlled clinical trials (NRS);

– randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs).

The exclusion criteria on which the reviewers agreed were as follows12:

– adult patients;

– studies have focused on pain or numbness of tissues without paying attention to self-inflicted trauma;

– articles not in English;

– opinions;

– editorial articles;

– review articles;

– it is not possible to access the full text;

– duplicate publications.

No restrictions have been applied with regard to the year of publication.

Sources of information, search strategy and selection of studies

In October 2024, a comprehensive search was performed in the PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases to identify articles that meet the predefined inclusion criteria. Additionally, searches were conducted in gray literature sources, including WorldCat, The New York Academy of Medicine Library and the Trip Database. The search criteria were meticulously crafted, utilizing a strategic blend of the specified keywords. For PubMed, we used ((biting[Title/Abstract]) OR (bite[Title/Abstract]) OR (traumatic injuries) OR (soft-tissue injury[Title/Abstract]) OR (soft tissue injury[Title/Abstract]) OR (self-inflicting injuries[Title/Abstract])) AND ((topical anesthesia[Title/Abstract]) OR (local anesthesia[Title/Abstract])) AND ((pediatric[Title/Abstract]) OR (children[Title/Abstract])). For WoS, we used ALL= ((biting OR bite OR Traumatic injuries OR Soft-tissue injury OR soft tissue injury OR self-inflicting injuries) AND (topical anesthesia OR local anesthesia) AND (pediatric OR children)). For Scopus, we used ((biting OR bite OR Traumatic injuries OR Soft-tissue injury OR soft tissue injury OR self-inflicting injuries) AND (topical anesthesia OR local anesthesia) AND (pediatric OR children)). For WorldCat and The New York Academy of Medicine Library, we used biting OR biting OR traumatic injuries OR soft tissue injuries OR soft tissue injuries OR self-inflicted injuries) AND (topical anesthesia OR local anesthesia) AND (pediatric or children. For Trip Database, we searched (self-inflicted injuries) AND (topical anesthesia OR local anesthesia) AND (children). Following the database search, a thorough and systematic literature review was conducted to identify any papers that were initially considered potentially irrelevant to this study. Only articles with available full-text versions were considered for inclusion.

Data collection process and data elements

Two reviewers (A.O. and J.K.) independently reviewed and extracted articles that met the inclusion criteria. Relevant data collected included the names of the authors, the year of publication, the study design, the title of the article, the type of laser used, and the results related to its effectiveness in the healing process and pain management. The extracted data was systematically recorded in a standardized Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2013; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) for subsequent analysis.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

During the initial selection phase of the study, each reviewer independently evaluated the titles and abstracts to minimize potential bias. The Cohen’s kappa test was used to assess the level of agreement among reviewers. Any discrepancies regarding the inclusion or exclusion of articles were resolved by the 3rd reviewer.13

Quality assessment

Two independent reviewers (A.O. and J.K.) systematically evaluated the methodological quality of each study to determine its suitability for inclusion. If there was a disagreement among the reviewers about whether to include a study, a 3rd reviewer was consulted to make the final decision. The quality assessment was conducted using a set of critical assessment tools designed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI; https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools). Cohen’s kappa test was conducted to evaluate inter-rater reliability using MedCalc v. 23.1.7 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). The analysis yielded a kappa value of 0.9 (p < 0.001), indicating almost perfect agreement and high consistency among the reviewers’ assessments.

Results

Selection of studies

An initial search of databases, including PubMed, WoS and Scopus, yielded a total of 574 studies potentially relevant for review. After the duplicate entries were removed, 438 articles remained for screening. During the preliminary evaluation of the titles and abstracts, 406 studies were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, 32 articles were subjected to a detailed analysis of the full text, which led to the exclusion of 5 articles for non-compliance with the inclusion criteria and 4 for unavailability of the full text. In the end, 21 articles were deemed eligible and included in the qualitative summary of this review.1, 4, 5, 6, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30

General characteristics of the studies included

This systematic review includes a wide range of studies examining the diagnosis and management of traumatic injuries resulting from local anesthesia in pediatric dentistry. The studies consist of RCTs,5, 6, 16, 17, 18, 21, 24, 25, 27 clinical cases1, 4, 14, 15, 23, 30 and cohort studies,19, 22, 26, 28 which reflects a comprehensive investigation into this topic. Sample sizes varied considerably between the included studies, with case reports focusing on individual patients or small groups1, 4, 14, 15, 23, 30 and large-scale studies that include up to several hundred participants.5, 19, 20, 22, 24, 25, 26, 29 A general feature of the included studies was demonstrated in Table 1.

Study participants ranged from children to adolescents, with most studies focusing on children aged 6–12 years, as this group is most commonly placed under local anesthesia during routine dental procedures.4, 5, 16, 18, 21, 30 A key theme in all studies is the high prevalence of self-inflicted soft tissue injuries after administration of local anesthesia. These lesions, which often affect the lips, cheeks or tongue, result from the temporary loss of sensation, leading to accidental bites and trauma.1, 4, 6, 14, 15, 17, 18, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30 Studies have also explored specific types of injuries, such as traumatic ulcers caused by unintentional tissue damage.1, 4, 14, 15, 23, 30

Anesthesia methods varied between studies and included traditional inferior alveolar nerve blocks,4, 6, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 23, 25, 26, 30 topical anesthetics14, 19 and innovative techniques such as computer-controlled intraosseous injections29 or intraligamental anesthesia.17 Comparison of these methods provided insight into the different risks and outcomes associated with the different techniques. For example, Helmy et al.17 highlighted the potential benefits of computer-controlled intraligamental injections in minimizing complications, while other studies have examined the relative effectiveness of bilateral compared to unilateral nerve blocks.25 In addition, the role of specific anesthetics, such as articaine and lidocaine, in terms of safety and duration of numbness was analyzed.26

Several studies have introduced innovative interventions to mitigate injury risks and improve recovery. These include the use of phentolamine mesylate5, 6 as well as non-pharmacological strategies, intraoral appliances designed to protect soft tissue from damage10 or unsweetened popsicles to reduce the tendency to bite and provide a soothing effect post-procedure.28 Photobiomodulation (PBMT) therapy has been prominently characterized as an effective approach to accelerate the reversal of local anesthesia, reducing the duration of numbness and potentially decreasing the risk of self-inflicted injury.16, 18 A detailed feature of the included studies was demonstrated in Table 2.

Main findings of the study

The studies included in this systematic review provide valuable insights into the diagnosis and management of traumatic injuries caused by local anesthesia in pediatric patients. A predominant finding reported in multiple studies has been the high incidence of lesions particularly on the lower lip, cheeks and tongue bites, which are directly attributed to residual numbness after administration of anesthesia.1, 4, 6, 14, 15, 17, 18, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30 These injuries often appear as ulcers or tears in the tissues, leading to discomfort, delayed healing and psychological distress in affected children.1, 4, 6, 14, 15, 23

Several studies have evaluated the effectiveness of innovative preventive strategies. Intraoral appliances significantly reduce the incidence of bite injuries by serving as mechanical barriers during the period of anesthesia-induced numbness.22 Similarly, non-pharmacological approaches, such as the use of icicles, have demonstrated potential to mitigate tissue trauma by promoting sensory awareness and calming post-operative behavior.28 The effectiveness of low-level laser therapy in speeding up anesthesia reversal and decreasing the duration of numbness has also been emphasized, with studies showing quicker recovery times and fewer complications.16, 18 A similar preventive strategy that introduced pharmacological intervention was applied in studies conducted by Tavares et al.5 and Nourbakhsh et al.,6 where phentolamine mesylate was administered to patients following the injection of local anesthesia. These methods have proven effective in shortening numbness duration after local anesthesia, thereby preventing self-inflicted soft tissue trauma.

Comparative results of different anesthesia techniques were another significant goal. Studies have found that computer-controlled intraligamental injections resulted in fewer postoperative injuries than traditional nerve block techniques, particularly in younger patients undergoing dental extractions.17 It happens due to the lack of anesthetization of local soft tissues – anesthesia is applied directly to the periodontal ligament of a treated tooth. Pain management and patient comfort have been evaluated in several studies, with results indicating that improved anesthetic techniques, such as intraosseous injections, can improve the patient experience by providing more localized and controlled anesthesia.29 The type of anesthetic agent used also influenced the outcomes; e.g., adverse effects such as prolonged numbness or an increased risk of soft tissue trauma have been linked to specific agents, such as articaine, particularly when administered at concentrations as high as 4%.26

The studies we reviewed show that different methods for preventing self-inflicted soft tissue injuries after local anesthesia vary in both safety and effectiveness. For example, phentolamine mesylate can cut down on how long a child stays numb, which lowers the chance of accidental bites,5, 6 though it might cause mild side effects like a brief drop in blood pressure or dizziness.31, 32 Photobiomodulation therapy can also speed up recovery from numbness and help tissues heal, but it is not always easy to access or afford.15, 16, 18 Non-drug strategies, such as using a custom mouth appliance or offering popsicles, can be effective in preventing biting; however, success largely depends on the child’s willingness to cooperate.20, 28 Meanwhile, alternative anesthesia techniques – like intraligamentary or intraosseous anesthesia – can significantly cut down on injuries, but they require special tools and training.17, 29

In the future, comparing these different methods in head-to-head studies will be helpful to determine which ones are most effective in various situations. We also need longer-term research to find out how well each approach holds up over time. Ultimately, creating clear guidelines for dentists – based on both practical experience and solid evidence – can help protect children from these injuries while ensuring they receive safe, comfortable dental care.5, 6, 15, 16, 18, 20, 28, 29

Quality assessment

Six case reports were assessed using a checklist, with 2 scoring the highest score by 8 points,14, 23 while the other 4 received 7 points1, 4 and 6 points.15, 30 Among the 9 RCTs, 5 had a low risk of bias, gaining 13 points,5 12 points17, 27 or 11 points6, 24 out of 13, while the other showed a moderate risk of sprain with a score of 9 points16, 25 or 10 points18, 21 on the 13 point-scale. In addition, 4 cohort studies were analyzed, with a score of 9 points,19, 7 points22 or 6 points26, 28 out of 11 possible. Score details for these studies are summarized in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5.

Discussion

This systematic review provided a comprehensive overview of the diagnosis and management of soft tissue injuries caused by local anesthesia in pediatric dental practice. The main findings highlight the high prevalence of traumatic lesions among pediatric patients, with the most common accidental bites to the lips, cheeks and tongue. These injuries are strongly associated with the temporary loss of sensation caused by local anesthesia, which impairs the child’s ability to perceive and control oral movements.1, 4, 15, 17, 18, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30 Many cases have emphasized the risk of soft tissue damage following inferior alveolar block anesthesia.4, 6, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 23, 25, 26, 30 Although generally self-limiting, these injuries can cause considerable discomfort and delay healing, as evidenced in previous work.1, 14, 15, 26, 30

Consistent with the results of Helmy et al.,17 anesthetic techniques significantly influence the incidence of postoperative trauma. In particular, computer-assisted intraligamentous anesthesia has been shown to reduce complications compared to traditional nerve block techniques. Computer-controlled anesthetic delivery is associated with reduced injection pain, better control of the anesthetized area and a decreased risk of traumatic bites by providing localized numbness without affecting surrounding soft tissues. This precise administration with preselected speed of anesthetic delivery not only enhances patient comfort but also minimizes post-procedural discomfort and swelling, leading to a smoother recovery.17, 18 In addition, innovative approaches such as PBMT and phentolamine mesylate have demonstrated efficacy in reducing the duration of anesthesia and minimizing self-inflicted lesions, in line with the results of previous studies.5, 6, 16, 18

The pharmacological approach to alleviating self-inflicted soft tissue injuries following local anesthesia includes the administration of reversal agents such as phentolamine mesylate. This adrenergic antagonist has been shown to significantly reduce the duration of anesthesia-induced numbness, decreasing the likelihood of accidental bites and associated trauma.31, 32 Its efficacy in expediting sensory recovery is particularly valuable in pediatric dentistry, where young patients may struggle with the unfamiliar sensation of prolonged numbness. However, while the benefits of phentolamine mesylate in reducing anesthesia-related injuries are well-documented, concerns remain regarding its potential side effects, including transient hypotension, dizziness and local tissue reactions.33 Additionally, repeated administration in the same anatomical area raises the risk of localized complications, such as tissue irritation or vascular compromise. These factors underscore the importance of exploring non-pharmacological and minimally invasive alternatives to improve patient safety and comfort.

The advantages of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) are especially significant in pediatric dentistry.34, 35 One of its primary benefits is the significant reduction in soft tissue recovery time, which promotes faster healing and minimizes discomfort in young patients.18 In addition, PBMT provides an effective analgesic effect, relieving pain without the need for pharmaceutical interventions.36 This is particularly valuable in pediatric populations, where the risk of adverse reactions to anesthesia can pose significant concerns.37, 38 Photobiomodulation therapy provides a noninvasive, drug-free method for managing self-inflicted injuries, such as accidental bites or trauma, which often occur due to residual numbness after local anesthesia.18 Low-level laser therapy harnesses the healing properties of light to stimulate cellular repair and reduce inflammation, making it a promising and safe option for injury treatment.35 Its ease of application and minimal risk profile further increase its potential as a valuable tool in pediatric dental care, providing both immediate relief and long-term benefits for young patients.16 However, there is limited research on the cost-effectiveness and accessibility of implementing PBMT in routine clinical practice, indicating a need for further studies to evaluate these aspects.39

The effectiveness of different methods to prevent self-inflicted soft tissue injuries after local anesthesia depends on the specific technique used, patient compliance and clinical feasibility. For instance, the use of phentolamine mesylate can accelerate the reversal of local anesthesia, thereby reducing the risk of accidental soft tissue injuries. However, it may also be associated with side effects such as transient hypotension or dizziness.4, 5, 29 Meanwhile, PBMT is a noninvasive option that helps tissues heal faster and reduces the duration of numbness without the need for additional medication.14, 16 Despite the promising benefits of PBMT, concerns remain about its availability, cost and the lack of standardized protocols for routine clinical practice.37 Non-pharmacological options, like intraoral appliances, have shown success in preventing accidental bites, especially in younger children.8 However, patient compliance and comfort play a crucial role, as some children may be reluctant to use these devices. Another simple method is giving children unsweetened popsicles as a sensory distraction to reduce biting behavior, but there is limited evidence regarding its long-term effectiveness or potential drawbacks.26 Even though these techniques are promising, direct comparisons of their safety, effectiveness and feasibility are lacking in the current literature. Most studies evaluate these interventions individually rather than in comparative trials, making it difficult to determine the most effective approach.

Preventive measures are critical in pediatric dental care to mitigate the risk of self-inflicted injury following procedures involving local anesthesia.38, 40 The use of protective intraoral devices has been shown to significantly reduce accidental bites. A study evaluating 3 types of self-designed intraoral appliances found them effective in preventing biting of the cheeks, lips and tongue in children after local anesthesia.20 In addition, non-pharmacological interventions, such as offering unsweetened popsicles after treatment, have demonstrated benefits.41, 42 Research indicates that children who received popsicles after dental procedures under local anesthesia experienced less discomfort and a reduced tendency to self-mutilation than those who received a toy.28 However, the literature does not extensively address the potential adverse effects of these preventive strategies. Nevertheless, given their noninvasive nature, these approaches are likely to pose fewer risks than pharmacological methods, which may be associated with systemic adverse effects.20

Caregivers play a vital role in preventing self-inflicted soft tissue injuries in children – especially younger or disabled patients – following local dental anesthesia. Due to temporary numbness, children may unintentionally bite or chew on their lips, cheeks or tongue, leading to painful injuries.4 To minimize this risk, caregivers should closely monitor the child until the anesthetic wears off, discourage eating solid foods or drinking hot beverages, and provide soft or cold foods instead.43 Additionally, engaging the child in distraction techniques, such as supervised play, can help reduce the likelihood of injury.19 Educating caregivers about these precautions is essential for ensuring a safe and comfortable recovery.44 These strategies not only improve postoperative comfort but also play a critical role in preventing complications associated with residual numbness, thereby improving the overall quality of pediatric dental care.38, 40, 41, 42, 45, 46

Limitations

This study has several limitations, including variability in anesthesia protocols, differences in dosages and administration methods and the heterogeneity of pediatric populations, which affect the generalizability of findings. The broad age range of examined children introduces additional variability, as younger and older children may respond differently to anesthesia and have distinct risks of self-inflicted injuries. The lack of longitudinal studies further limits insights into long-term effects, such as cognitive or developmental outcomes. Future research should focus on standardized protocols, narrower age groups and larger, more diverse control groups. In addition, the considerable variability among the studies included prevents us from performing a meta-analysis. However, additional research is needed to make a meta-analysis feasible.

Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the high prevalence of self-inflicted soft tissue injuries among pediatric dental patients, caused primarily by residual numbness after local anesthesia. The findings underscore the need for comprehensive preventive and therapeutic strategies to effectively address these complications. Innovative approaches such as computerized anesthesia, PBMT and protective intraoral devices have shown significant potential in reducing the incidence of accidental bites and enhancing recovery outcomes. However, the variability of anesthetic protocols and study methodologies underscores the need for standardized practices and further research. Longitudinal studies are essential for evaluating the long-term effects of these interventions, ensuring safety and validating their efficacy in diverse pediatric populations. To enhance clinical application, dental practitioners should prioritize patient and caregiver education on post-anesthetic care, incorporate intraoral protective devices when appropriate, and consider alternative anesthesia techniques to minimize residual numbness. Additionally, implementing structured post-procedure monitoring can help identify and mitigate potential injuries early. By integrating these advanced, minimally invasive approaches, pediatric dental care can prioritize both patient safety and comfort while addressing the unique challenges of soft tissue injury management.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.