Abstract

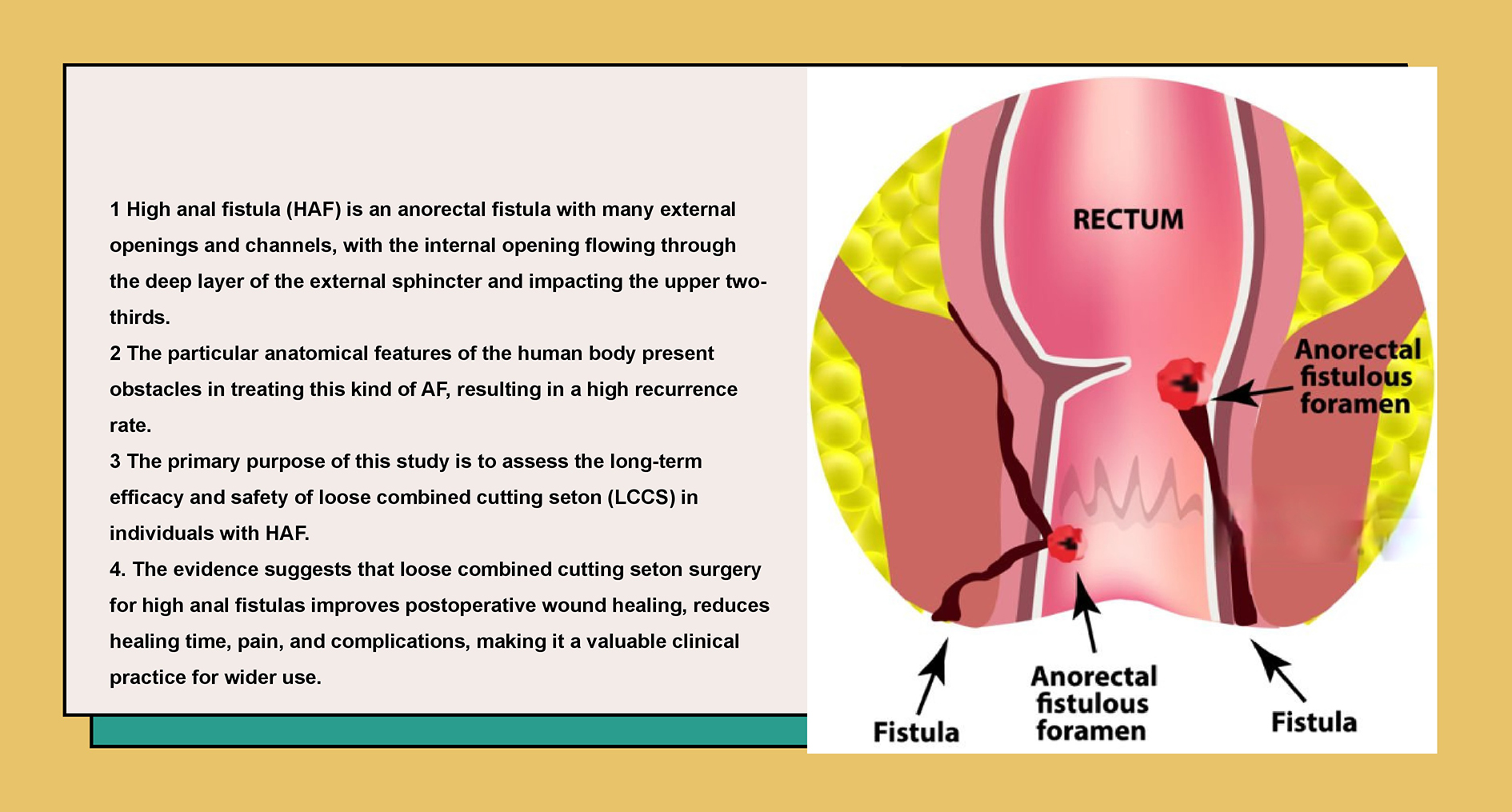

Background. The healing rate after treatment in patients with high anal fistula (HAF) remains low. In individuals with HAF, the loose combined cutting seton (LCCS) technique has shown promising effectiveness, demonstrating a high cure rate, low incidence of incontinence and reduced pain levels.

Objectives. To assess the long-term efficacy and safety of LCCS technique in patients with HAF.

Materials and methods. The LCCS procedure was conducted in patients with HAF between December 2020 and February 2022. All participants were followed up for 12 months. The primary outcome was fistula healing, while secondary outcomes included fistula recurrence, visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score, severity of fecal incontinence, and quality of life.

Results. A total of 132 patients with HAF were included in the final analysis, with a mean follow-up duration of 17.0 ±3.8 months. At the 12-month follow-up, 130 patients (98.5%) achieved fistula healing. Among them, 103 patients who received primary HAF treatment at our center fully recovered, while 27 of 29 patients previously treated unsuccessfully at other hospitals achieved healing within 12 months, corresponding to a 93.1% success rate. Ninety patients (68.2%) reported no fecal incontinence at follow-up (Wexner Continence Grading Scale (WCGS) score = 0), and 42 patients had a WCGS score of 1. The LCCS procedure was associated with a persistently low risk of postoperative perianal discomfort, with 127 patients (96.2%) scoring 0 and only 5 (3.8%) scoring 1 on the VAS.

Conclusions. The LCCS technique is a safe and effective treatment for patients with HAF.

Key words: safety, efficacy, high anal fistula, loose combined cutting seton

Background

Anal fistula (AF) is a prevalent anorectal disorder, particularly affecting younger males. Epidemiological data estimate that AF affects approx. 8% of the population in Western countries and 3.6% in China.1, 2, 3 High anal fistula (HAF) is characterized by multiple external openings and tracts, with the internal opening traversing the deep portion of the external sphincter, specifically involving the upper two-thirds of the muscle. The intricate anatomical features of the anorectal region present substantial challenges in the management of HAF, contributing to a significant recurrence rate.4, 5

Inadequate treatment of HAF can disrupt the physiology of adjacent tissues and significantly affect patients’ health and quality of life. Therapeutic objectives for HAF primarily focus on fistula healing, recurrence prevention and bowel function improvement.5, 6 Current clinical practice employs diverse therapeutic modalities to address HAF, including fibrin sealant, fistula plug, ligation of the inter-sphincteric fistula tract (LIFT), endorectal or dermal advancement flap, video-assisted AF treatment, and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Despite these advances, reported healing rates remain suboptimal.8, 12

Seton-based techniques have demonstrated efficacy in the management of HAF, offering high cure rate with a low risk of incontinence. Recent advancements in seton materials and application methods improved outcomes,13, 14 though reported recurrence rates still range from 8% to 22%. Clinical implementation remains heavily dependent on surgical expertise.15, 16, 17 The loose seton technique facilitates effective drainage and accelerates the healing process while minimizing the risk of sphincter injury.13 However, in some cases, excessive fibrosis may lead to treatment failure. Conversely, the cutting seton achieves definitive fistula resolution through progressive sphincter division; however, it is frequently associated with complications such as pain and fecal incontinence.18

To effectively manage HAF and improve patients’ quality of life, it is essential to develop treatment approaches that achieve high healing rate while minimizing recurrence, incontinence and pain. Our prior retrospective study demonstrated that a combined virtual and solid wiring offers superior clinical outcomes compared to traditional solid seton techniques, particularly in reducing healing time and alleviating pain.19 In this approach, the virtual seton facilitates drainage, whereas the solid seton progressively transects the fistulous tract. Nonetheless, the long-term postoperative recurrence, anal incontinence and recovery of anal function represent paramount determinants of surgical efficacy and quality of life following HAF repair. However, longitudinal data quantifying these critical long-term outcomes remain scarce.

Objectives

This prospective cohort study aims to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of loose combined cutting seton (LCCS) in patients with HAF.

Materials and methods

This was a prospective cohort study.

Study population

The study was conducted at the Anal and Intestinal Department of China-Japan Friendship Hospital (Beijing, China), a national referral center specializing in the treatment of over 1,000 patients annually with various types of AFs, serving individuals from across the country and abroad. This study included consecutive patients diagnosed with HAF who underwent surgical treatment at the Second Department of Anorectal Surgery of China-Japan Friendship Hospital between December 2020 and February 2022. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) individuals aged 18 years or older, and 2) a definitive diagnosis of HAF, including primary HAF and failed cases from other medical centers. The exclusion criteria included: 1) individuals with colorectal cancer, 2) inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or intestinal tuberculosis, 3) autoimmune diseases, 4) coagulation dysfunction, 5) systemic infections related to acquired immunodeficiency disease, 6) severe cardiopulmonary dysfunction, 7) life expectancy of less than 12 months, 8) pregnancy or lactation, and 9) inability to comply with long-term follow-up. Patients with missing primary indicators were also excluded from the final analysis. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of China-Japan Friendship Hospital (approval No. 2022-KY-121-2), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This investigation adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration (2013 edition).

Surgery

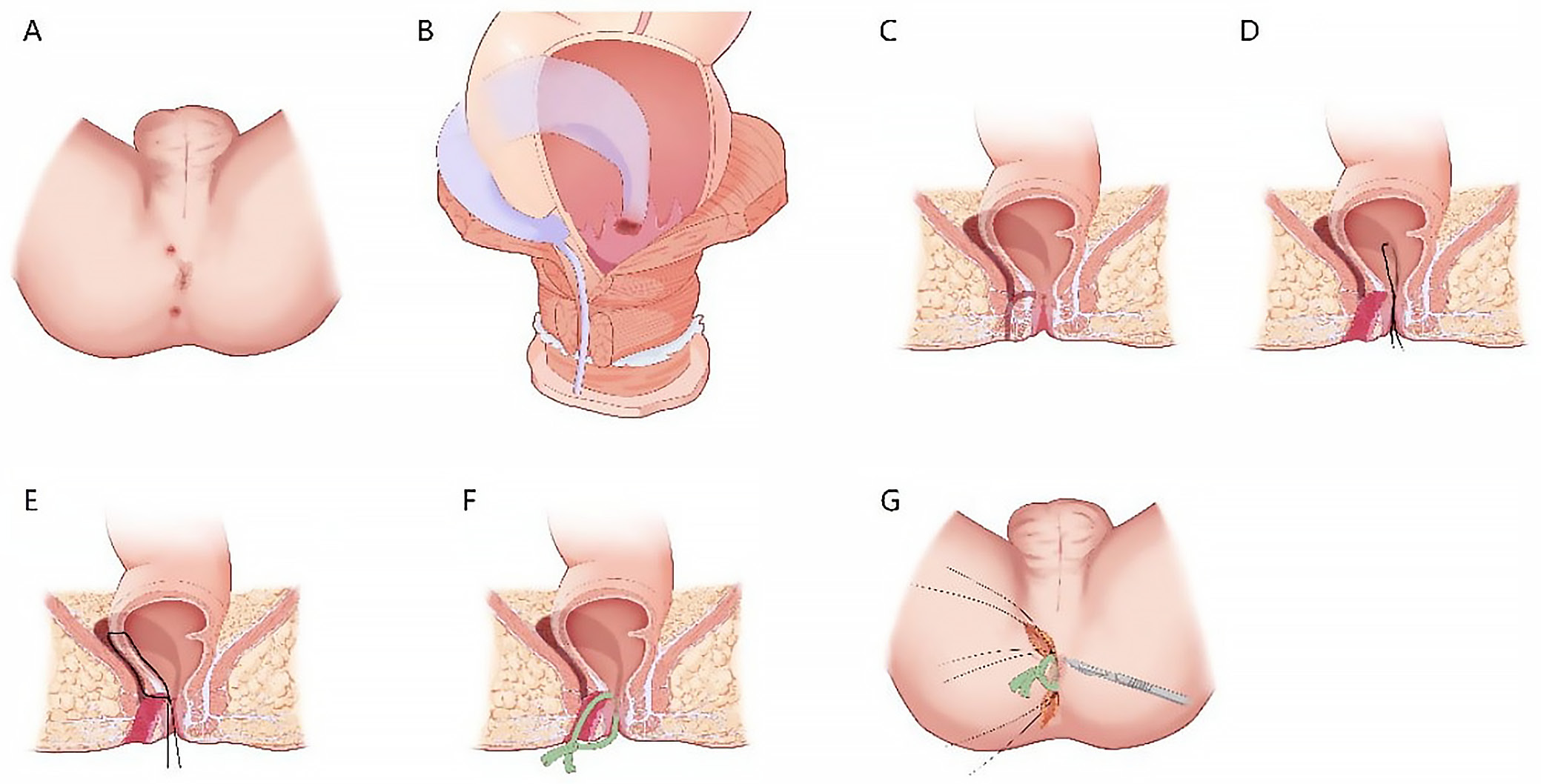

All procedures were performed by the same surgical team (Z.L.H., C.Y.C., Z.C.C., and L.N.Y.) using the LCCS technique as previously described (Figure 1).19 Patients received general or epidural anesthesia and were positioned laterally to facilitate access to the fistula. Following standard perineal disinfection with 0.5% iodophor, the anal canal was adequately relaxed. A digital rectal examination was performed in conjunction with anorectal B-ultrasound findings to evaluate the internal opening of the fistula, its extent, the presence of branched tracts or necrotic tissue, and any indurated masses around the anorectal ring. A fistula probe was introduced through the external opening. If the fistula lacked an external opening, the distal end was excised to create an access point. The probe was introduced into the internal orifice along the fistula tract, and the fistula wall was meticulously dissected layer by layer to facilitate complete exposure. Tissue surrounding the internal orifice was excised to a margin of 0.5–1.0 cm. The probe was carefully advanced from the internal orifice upward through the fistula tract, assisted by curved hemostatic forceps, while a finger was inserted into the rectal cavity to locate the fistula apex. The forceps’ tip was employed to access the stoma of the intestinal wall, which served as the focal point of the crisscrossed lumps. Subsequently, the examining finger was withdrawn, and 4 No. 10 silk threads were affixed to the fingertips at one end before being introduced into the enteric cavity. The threads were subsequently secured using hemostatic forceps, extracted from the stoma of the intestinal cavity along the fistula, tightened at both ends, and tied off for stabilization.

Postoperative wound management involved daily dressing changes adhering to standard disinfection protocols. Oil gauze was utilized to facilitate drainage, while standard gauze was used to secure external applications. All patients received intravenous analgesics (flurbiprofen axetil injection, 100 mg, each day) and antibiotics (etamycin sulfate and sodium chloride injection, 300 mL, each day) for 2 days post-surgery. The ligature was observed to loosen on postoperative day 7 but was left in situ to maintain drainage. Based on the characteristics of the granulation tissue developing within the fistula tract, the silk thread was removed on postoperative day 20. Dressings were changed regularly thereafter until complete wound healing was achieved.

Data collection

Data were collected on patient demographics, medical history, comorbidities, fistula characteristics, surgical procedure, and clinical outcomes. Prior to the surgical procedure, all patients underwent a comprehensive baseline assessment, including routine blood tests, assessments of liver and renal function, and evaluation of blood glucose and lipid profiles. Furthermore, a subset of patients underwent endoanal ultrasonography and anorectal pressure manometry to determine the position of the internal orifice and the configuration of the fistula. Follow-up assessments were conducted at the outpatient clinic 12 months post-surgery. These evaluations included a physical examination (comprising anal inspection and digital rectal examination), endoanal ultrasonography and anorectal manometry. Patients experiencing severe symptoms or concerns regarding recurrence were advised to undergo additional clinical review.

Fistula healing was defined by the complete closure of the surgical incision, absence of secretions, and the lack of any detectable fistula as confirmed using endoanal ultrasonography. Recurrence was diagnosed if a patient met at least 1 of the following criteria: 1) non-healing of the surgical wound beyond 3 months, 2) persistent discharge beyond 3 months, 3) endoanal ultrasonography indicated the presence of the fistula, or 4) clinical necessity for reoperation.

A visual analogue scale (VAS) was employed to assess postoperative pain, with scores ranging from 0 (indicating no pain) to 10 (representing extremely severe pain). The severity of fecal incontinence was evaluated through the Wexner Continence Grading Scale (WCGS), encompassing 5 domains: solid, liquid, gas, pad wearing, and lifestyle alterations. Each domain was assigned a score ranging from 0 (indicating no incontinence) to 4 (indicating severe incontinence). The quality of life was evaluated using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36).

Outcomes

The primary outcome variable of this investigation was fistula healing rate. Secondary outcomes included the fistula recurrence rate, postoperative pain (VAS), fecal incontinence severity (WCGS), and quality of life (SF-36).

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normal distributions tested by Kolmogorov–

Smirnov test. Numerical and percentage representations were used for categorical variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS v. 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). A 2-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Missing data for certain variables were excluded from the analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Following the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 132 patients with HAF were included in the final analysis, comprising 114 men (86.4%) and 18 women (13.6%). Of these, 29 patients had previously undergone unsuccessful LIFT surgery at other medical centers. Detailed baseline characteristics prior to LCCS treatment are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

The median duration of HAF was 12 months (interquartile range (IQR): 2–36 months). The most common presenting symptoms were perianal pain (n = 116, 87.9%), perianal mass (n = 97, 73.5%), anal secretion (n = 83, 62.9%), anal pendent expansion (n = 35, 26.5%), and fever (n = 21, 15.9%). The majority of patients had a single fistula tract, characterized by 1 external orifice. The internal orifice was located at the 6 o’clock position in 111 (84.1%) patients and at 7 o’clock position in 12 (9.1%) patients, while an additional 9 patients (6.8%) exhibited internal orifices at both 1 and 6 o’clock, respectively. A semi-horseshoe shape fistula was identified in 71 patients (53.8%), a full horseshoe in 43 patients (32.6%) and homotopic line in 18 patients (13.6%). The preoperative laboratory findings of the patients are presented in Table 3. All patients exhibited normal liver function and renal function, with no significant abnormalities noted.

Primary outcome

The mean follow-up duration was 17.0 ±3.8 months. At the 12-month postoperative follow-up, 130 of 132 patients achieved fistula healing, yielding an overall healing rate of 98.5%. Among the 103 patients undergoing HAF treatment for the first time, the 12-month healing rate was 100%. Of 29 patients with prior treatment failures from external center, 27 achieved healing at 12-month follow-up, resulting in healing rate of 93.1%. Recurrence was observed in 2 patients at 10 and 11 months post-surgery, corresponding to an overall recurrence rate of 1.5%.

Secondary outcome

The WCGS assessment revealed that 90 patients (68.2%) exhibited no fecal incontinence during follow-up, corresponding to a WCGS score of 0. The remaining 42 patients reported a WCGS score of 1. The median total WCGS score was 0 (range: 0–12). The median total WCGS score was 0 for patient groups without previous surgery (range: 0–3) and 29 patients with failed surgeries before (range: 0–12). A total of 27 patients reported “occasional” liquid stool incontinence. Additionally, 5 patients experienced “occasional” flatus incontinence, and 9 patients reported “occasional” solid stool incontinence. Furthermore, 1 patient reported changes in their lifestyle. No patients exhibited anal itching (Table 4). At the 1-month postoperative follow-up, 127 patients (96.2%) reported a VAS pain score of 0, while 5 patients (3.8%) reported a score of 1. Notably, 3 of these patients no longer report any pain at the 3-month follow-up, suggesting that LCCS is associated with a long-term low risk of postoperative perianal pain. All patients achieved a final score of 100 in each SF-36 domain, indicating that the adverse effects of HAF on patients’ general health, physical activities, physical health, emotional health, social activities, and pain were nearly eliminated during the long-term follow-up after LCCS surgery.

Anal inspection revealed scar-related clots formation in 6 patients (4.5%), while no malformations were observed in any of the patients. Digital rectal examination confirmed the absence of palpable masses, induration or tenderness in all patients. Endoanal ultrasonography was performed in 132 patients postoperatively. The results indicated that all patients exhibited normal endoanal hypoechogenicity, with no evidence of gas or liquid shadow detected. Endoscopic ultrasonography identified a soft scar in 96 patients, accounting for 72.7% of the total cases.

Table 3 presents the results of postoperative anorectal manometry in 66 patients. The mean anal resting pressure, maximum systolic pressure and rectoanal pressure difference were 77.2 mm Hg, 140.5 mm Hg and 63.8 mm Hg, respectively. The mean high-pressure zone length was 4.1 cm. A recto-anal inhibitory reflex was observed in 57 patients (43.2%). Representative cases are illustrated in Figure 2, Figure 3.

Safety

Throughout the postoperative hospitalization and follow-up period, no patients experienced fever, local swelling or pus in the surgical area. Additionally, there were no recorded cases of postoperative hemorrhage or subcutaneous hematoma.

Discussion

High anal fistula represents a complex subtype of AF characterized by intricate branching patterns, posing significant challenges in diagnosis and treatment. These complexities often lead to relapse or delayed healing following surgical intervention, resulting in substantial physical and psychological burdens that markedly impair patients’ quality of life. As a national specialized center, our department has devoted the past decade to the clinical management and research of AF, particularly HAF. This work integrates the traditional principles of “deficiency and excess” with thread hanging technique. In this prospective cohort study, we observed a 3-month healing rate of 99.2% following treatment of HAF using a combination of deficiency and excess suturing, with the 12-month healing rate reaching 98.5%. Notably, primary intervention using this approach yielded 100% healing. Furthermore, over 2/3 of patients reported no postoperative fecal incontinence, while the remaining patients exhibited only minimal symptoms (WCGS score of 1). Additionally, 96.2% of patients experienced complete resolution of anal or perianal pain after surgery with the combined deficiency and excess thread-hanging method.

Our clinical observations suggest that the anatomical morphology of HAF is not solely characterized by interwoven tubular infectious foci, as traditionally described, but rather by multiple lacuna-like infectious foci. Traditional tubular excision techniques carry the risk of leaving fissured extensions within these anatomical recesses, which may lead to incomplete resection and subsequent recurrence. Moreover, excessive excision of necrotic tissue may enlarge the size and depth of the AF cavity. The absence of oxygen in this space is attributed to the compression exerted by adjacent tissues, particularly the muscles, leading to a closed and hypoxic condition. This oxygen-deficient space fosters persistent or recurrent infection. This concept forms the basis of what we term the “lacuna theory” of HAF. Accordingly, we are actively refining our surgical protocol by incorporating virtual reality (VR)-assisted visualization into the thread-hanging technique. This approach underscores the meticulous excision of AF during the operation to thoroughly reveal the focus of the AF. It emphasizes meticulous excision of superficial necrotic tissue, coupled with manual exploration to delineate the pus cavity, thereby enhancing drainage. Solid thread suspension is employed for precise tissue incision, while virtual thread suspension facilitates effective drainage. Compared to conventional techniques, our treatment approach may involve a larger perianal incision; however, this allows for a more comprehensive exposure of the AF cavity.

The integration of VR and thread hanging facilitates effective drainage while minimizing harm to the anorectal ring, thus achieving radical fistula eradication and preserving anal sphincter function. Our findings indicate that the integration of deficiency and excess with thread-hanging therapy yields a significant healing rate. Patients who have not responded to previous treatments achieved a remarkable 12-month healing rate of 98.5%. During the 12-month postoperative follow-up, the majority of patients did not report any further incidents of fecal incontinence. In contrast, approx. 1/3 of the patients experienced occasional mild fecal incontinence, primarily attributed to unrelated intestinal inflammation. These outcomes suggest that our approach effectively preserves anal sphincter function. Additionally, the absence of pain in and around the anus indicates that this method may result in reduced local tissue damage, offering a more comprehensive and less invasive treatment option. The resolution of anal fistula, restoration of anal function and reduction of pain collectively contributed to an improved quality of life for patients.

Current international HAF management strategies include LIFT, fibrin glue sealant, AF plug, video-assisted AF treatment (VAAFT), photodynamic therapy (PDT), and fistula-tract laser closure (FiLaC™). Nonetheless, the healing rate associated with these treatments remains suboptimal. The LIFT procedure, first described by Rojanasakul et al., has been extensively evaluated.20 A meta-analysis by Emile et al., encompassing 26 studies and 1,378 patients, reported a pooled success rate of 76% and a complication rate of 14%. Furthermore, this procedure is not appropriate for individuals with high-level trans-sphincter fistulas, anal fissures located above the sphincter, or cases with prior surgical scarring that complicates intersphincteric separation.10 Lindsey et al. demonstrated that the healing rates for simple and complex AFs treated with fibrin glue were 50% and 69%, respectively.21

The findings from Adamina et al. indicated that AF suppositories may provide superior protection for anal function in complex AF; however, the cure rate remains approx. 50%.22 Garg et al. conducted a systematic evaluation and meta-analysis involving 786 patients to assess the efficacy of VAAFT in treating AF. The findings indicated an overall success rate of 76.01% and a complication rate of 16.2%, with no reported cases of anal incontinence.23 Arroyo et al. conducted a study involving PDT on 49 patients with complex AF, achieving an overall healing rate of 65.3%. One patient experienced phototoxicity, while 2 patients developed fever within 48 h post-surgery.24 FiLaC, as studied by Marref et al. in 69 patients with a median follow-up of 6.3 months, achieved a healing rate of 45.6%, with no new cases of anal incontinence and stable outcomes in patients with pre-existing incontinence. Notably, a 60% healing rate was observed in high sphincter AF cases.25 These findings highlight that, while alternative treatments offer benefits, their success rates remain suboptimal, and certain modalities carry a notable risk of complications.

In contrast to the aforementioned treatment methods, our approach integrating VR with thread hanging relies exclusively on conventional surgical instruments, eliminating the need for specialized equipment. This streamlined methodology significantly reduces operative duration, thereby lowering procedural costs and potentially decreasing anesthetic-related risks for patients. Furthermore, our strategy ensures comprehensive lesion exposure, facilitates effective drainage and necessitates prophylaxis with oral antibiotics for just 3–5 days during the perioperative period. By minimizing excessive debridement, this approach mitigates unnecessary tissue trauma. Our findings demonstrated no instances of postoperative systemic infections, with only 1 patient experiencing delayed incision healing within 1 month post-surgery, likely due to postoperative constipation, but without associated fever. Consequently, the approach we implemented offers significant security and ease of use. In clinical practice, it has been observed that certain patients may be able to forgo antibiotics following comprehensive debridement. This approach can minimize the likelihood of adverse reactions associated with antibiotic treatment, as well as decrease the chances of bacterial resistance. Beyond the LCCS technique, emerging therapies such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) warrant consideration, as prior studies have demonstrated its efficacy in various conditions, including HAF.26, 27 Future research should explore the integration of such adjunctive therapies to further optimize outcomes for HAF.

Limitations

Our investigation acknowledged certain limitations. Initially, it is important to note that this was a prospective cohort study rather than a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The primary rationale for employing this study design stems from our earlier clinical observations indicating a cure rate exceeding 95% for HAF treated with LCCS and thread-hanging therapy. In the context of a RCT, it is possible that certain patients within the control group could face preventable nonunion or recurrence. Second, this investigation was conducted at a single center, and our treatment methodologies and operational practices may vary from those of other medical institutions, potentially impacting the generalizability of our findings. Third, the inclusion of patients with prior unsuccessful treatments from other facilities may introduce heterogeneity in our cohort. Additionally, as a specialized center, our department manages a disproportionately high volume of HAF cases, which may contribute to selection bias. Fourth, the follow-up period was limited to 12 months, necessitating further investigation to ascertain the long-term efficacy of deficiency and excess combined with thread-hanging. Finally, this study did not include HAF resulting from tumors, IBD, intestinal tuberculosis, or other causes, which may restrict the applicability of our findings to these subgroups. Nonetheless, the effectiveness and safety of addressing deficiency and excess in conjunction with thread hanging for these patients require clarification through additional investigation.

Conclusions

The evidence from this study indicates that loose combined cutting seton surgery for HAFs significantly enhances postoperative wound healing, reduces healing time, alleviates pain, and lowers the rate of postoperative complications. These findings support its adoption as a valuable and effective approach in clinical practice, with potential for broader implementation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15075155.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.