Abstract

Congenital heart disease (CHD) remains the foremost cause of mortality in children under 20 years of age. Given their ease of harvest, robust proliferative capacity and multilineage differentiation potential, stem cells (SCs) have emerged as a promising therapeutic alternative. In particular, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from Wharton’s jelly in the umbilical cord, i.e., an abundant byproduct of childbirth, especially in low- and middle-income settings, can be induced toward a cardiomyocyte lineage, making them an attractive cell source for cardiac regeneration. Although MSCs can be directed toward a cardiomyocyte lineage using growth factors or chemical cues, most in vitro-differentiated cells remain developmentally immature, with only a small fraction achieving the structural, functional and metabolic maturity required for therapeutic use. In resource-limited laboratories, the primary challenge is to develop a simple, cost-effective protocol that reliably differentiates MSCs into structurally, functionally and metabolically mature cardiomyocytes. This review presents a streamlined, cost-effective in vitro differentiation protocol for umbilical-cord MSCs into cardiomyocytes, designed for laboratories with minimal resources, involving 3 sequential stages. First, induce cardiac mesoderm commitment by treating umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) with 5-azacytidine (5-Aza) or bone morphogenetic protein (BMP). Next, specify cardiac progenitor cells by adding a Wnt-pathway inhibitor (e.g., IWP-2). Finally, drive cardiomyocyte maturation by supplementing the culture with insulin-like growth factors (IGFs). In laboratories lacking complex bioreactors, seeding the cells onto a simple biocompatible scaffold, such as a collagen or fibrin hydrogel, can further boost differentiation efficiency and promote tissue-like organization.

Key words: cardiomyocyte, cell- and tissue-based therapy, differentiation, growth factor, mesenchymal stem cells

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 17.9 million deaths annually.1 Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common cause of mortality in children and adolescents under 20 years of age. A key challenge in CHD management is the heart’s inability to regenerate cardiomyocytes irreversibly lost after myocardial infarction. Myocarditis and cardiomyopathy, although typically acquired rather than congenital, are important contributors to pediatric heart disease, affecting approx. 1 in 100,000 individuals under 20 years of age. Structural cardiac malformations and cardiomyopathic changes that impair myocardial function often lead to heart failure in this population. Although heart transplantation remains the definitive treatment for end-stage disease, its use is severely limited by the scarcity of suitable donor organs.2, 3, 4

Children with CHD experience high mortality rates in the first 4 years of life, with few surviving to their 5th birthday owing to serious complications and comorbidities.5 This burden falls disproportionately on low- and lower-middle-income countries (LICs and LMICs), where the birth prevalence of CHD continues to rise even as diagnostic infrastructure and trained personnel remain scarce. Although timely surgical interventions can significantly reduce mortality, many health systems in these regions lack the resources required to provide them.6

However, cardiomyocytes are terminally differentiated and possess only a limited capacity for proliferation. Because primary adult human cardiomyocytes are difficult to obtain and embryonic stem cells (SCs) raise ethical and biological concerns, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are multipotent, readily available and exhibit low immunogenicity, offer a promising alternative for cardiac regenerative therapies.7 Mesenchymal stem cells can be harvested from a variety of tissues, including endometrium, placenta, dental pulp, amniotic fluid, adipose tissue, Wharton’s jelly (from the umbilical cord), bone marrow, and dermis, and can differentiate in vitro into osteocytes, adipocytes, neurons, chondrocytes, and cardiomyocytes.8, 9 Wharton’s jelly is especially attractive as an MSC source because it is readily available as medical waste, facilitates easy isolation and expansion, and exhibits a high proliferative capacity, making it particularly valuable for cardiac regenerative applications in LICs and LMICs.

Functionally mature cardiomyocytes display spontaneous contractile activity in vitro, a property that is essential for modeling cardiac pathophysiology.10, 11 In addition to serving as a research platform, these cells offer the potential to replace damaged myocardium.12 Consequently, SC-based therapies, chosen for their accessibility, robust proliferative capacity and multilineage differentiation potential, are under investigation as novel approaches for cardiac regeneration.7

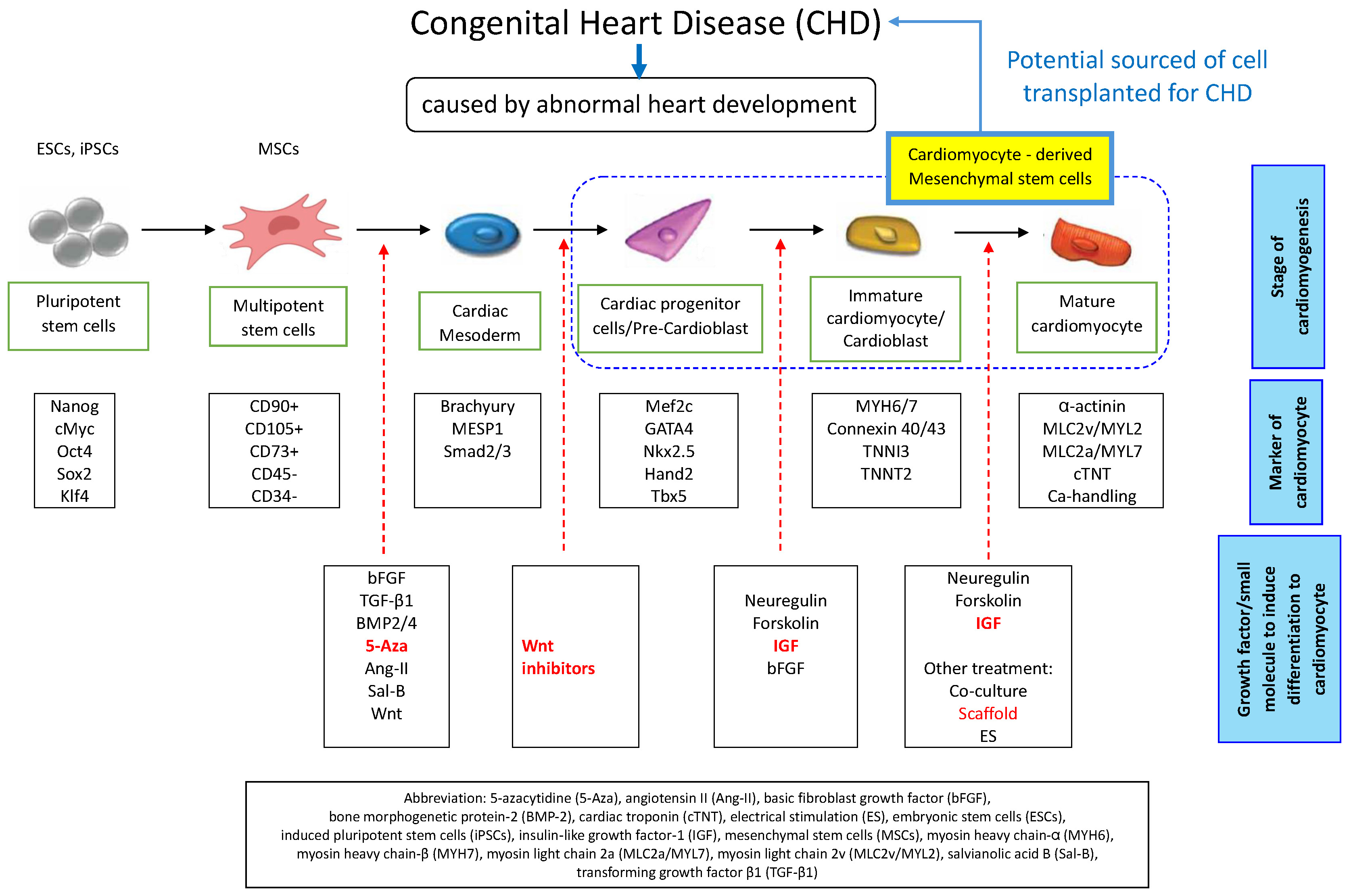

Similar to the in vivo procedure, MSCs can differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro with initial induction towards the mesoderm, cardiac progenitor cells or pre-cardioblasts, immature cardiomyocytes or cardioblasts, and mature cardiomyocytes.13 Several studies show that the MSCs can develop into cardiomyocytes in vitro by showing the expression of specific markers like cardiac troponin I (cTnI), cardiac troponin-T (cTnT), desmin, Nkx2.5, GATA-4, and connexin 43 (Cx43).14, 15 The cells grow in combination on a biomaterial scaffold with the proper biophysics and chemical signaling in the triad of tissue engineering techniques to generate a specific tissue.16

Protocols for directing pluripotent SCs toward differentiating into cardiomyocytes are under development. Several approaches have been established to induce cardiomyogenic differentiation in both induced pluripotent SCs (iPSCs) and MSCs. Previous studies have demonstrated MSC differentiation efficiencies of 20–50%,17, 18, 19 often achieved by treating cells with the DNA demethylating agent 5-azacytidine (5-Aza) to trigger cardiomyogenic commitment.20, 21

Although protocols for differentiating MSCs into cardiomyocytes are rapidly advancing, their broader application is hindered by a lack of standardized methodologies across research laboratories.22 Moreover, current differentiation protocols yield predominantly immature cardiomyocytes, with only a small fraction achieving the structural, functional and metabolic maturity required for therapeutic applications.

Therefore, the biggest hurdle for laboratories with limited resources is to find a simple and cost-effective method for differentiating MSCs into mature cardiomyocytes. This method should use accessible reagents, rely on a sustainable in-house differentiation medium and maintain optimal efficiency.

Objectives

This article aims to provide a simple protocol for differentiating the umbilical cord MSCs into cardiomyocytes in a laboratory with limited resources.

Materials and methods

This review is based on a comprehensive literature search conducted in the PubMed database. We searched PubMed (up to 2023) to identify relevant studies with the key words: “mesenchymal stem cell*” OR “mesenchymal progenitor cell*” OR “mesenchymal stromal cell*” AND “differentiat*” AND “cardiomyocyte*” OR “cardiac cell*” OR “cardiovascular” OR “heart muscle cell*” AND “in vitro” NOT “in vivo” (Table 1). Articles from the last 10 years were collected and selected based on the recommended topic; then, inclusion criteria were applied to filter the literature search results. We included peer-reviewed articles published in the last 10 years indexed in PubMed using relevant key words for MSC-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation, and excluded studies that did not employ defined induction factors. The initial search retrieved 86 articles; after title and abstract screening, 63 were deemed irrelevant, leaving 23 for full-text review. Six of these failed to meet our inclusion criteria, resulting in 17 studies ultimately incorporated into this analysis (Figure 1).

Results

Mesenchymal stem cells can be directed in vitro to differentiate into mesoderm-derived lineages such as cardiomyocytes by applying tailored cocktails of growth factors and small molecules that mimic cardiac development signals. Commonly used inducers include basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), salvianolic acid B, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), demethylating agent 5-Aza, neuregulin-1 (NRG-1), forskolin, angiotensin II (Ang-II), and an oligosaccharide extract of Rehmannia glutinosa (RGO). Each component contributes to cardiac mesoderm specification, activation of cardiogenic gene networks, and promotion of structural and functional maturation (Table 2, Table 3).17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37

Cardiovascular diseases in children

The most common form of CHD is the non-cyanotic type, which presents without cyanosis and typically arises from an intracardiac septal defect that creates a left-to-right shunt. In this condition, a gap in the septum allows oxygenated blood to flow from one heart chamber to another.38 Congenital heart disease results from disrupted cardiac morphogenesis during early gestation – typically around the 6th week – when the fetal heart and great vessels are forming. It remains the leading cause of mortality among newborns with congenital anomalies.39, 40

Congenital heart disease may result from a septal defect – such as an atrial or ventricular septal defect – that allows abnormal shunting of blood between the heart chambers. It can also arise from a patent ductus arteriosus, in which the fetal vessel connecting the pulmonary artery to the aorta fails to close after birth. Other forms include anomalous pulmonary venous return and transposition of the great arteries, where the aorta and pulmonary artery are reversed in position.41

Congenital heart disease spans a spectrum from asymptomatic, mild lesions – often undetected on routine physical examination – to critical defects that present immediately after birth and require urgent intervention. While subtle cases can go unnoticed without imaging, advances in echocardiography now enable reliable detection of most septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, anomalous pulmonary venous return, and transposition of the great arteries, facilitating timely diagnosis and management.39

The mortality rate among CHD patients is highest during the 1st year of life.42 The LICs and LMICs are especially impacted, and congenital disabilities have been related to increased newborn mortality rates. The birth prevalence of CHD is increasing in LICs and LMICs, and there is substantial evidence that surgery reduces the disease burden. In many LICs and LMICs, the identification of CHD is hampered by under-resourced health systems and a shortage of trained personnel.6

Current management of CHD

Treatment of CHD aims to correct anatomic defects and manage their sequelae. Intervention should be undertaken at the earliest feasible opportunity, with surgical repair representing the standard of care. However, not all patients are candidates for corrective surgery.43 The following strategies may be employed in CHD management:

Drug usage

Medication regimens, including β-blockers, diuretics, prostaglandins, digoxin, and sacubitril, are tailored in dose and timing to the specific cardiac lesion to reduce myocardial workload and enhance ventricular function.44 When bradyarrhythmias or conduction defects impair cardiac output, implantation of a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator provides essential rhythm support and helps prevent complications associated with congenital conduction abnormalities.45

Catheter-based interventions

Catheter-based interventional cardiology enables the repair of CHD without open surgery. Under fluoroscopic and echocardiographic guidance, a thin, flexible catheter is introduced – typically via the femoral vessels – and navigated to the cardiac lesion. Once in position, specialized devices (such as balloons, occlusion plugs or stents) are delivered through the catheter to correct septal defects, relieve valvular stenosis or address vascular obstructions. This minimally invasive approach allows for avoiding surgical incisions, minimizes tissue trauma and generally reduces hospital stays and overall costs.46, 47, 48, 49 World Bank estimates indicate that Asia and Africa each have fewer than 1 cardiac catheterization laboratory per 1,000,000 inhabitants. Many low-income African nations lack any functional cardiac catheterization laboratory, leaving large portions of their populations without access to essential tertiary cardiac care.6

Heart surgery

When catheter-based interventions are insufficient to correct CHD, open-heart surgery becomes necessary. Surgical procedures aim to repair or replace malformed valves, enlarge constricted vessels and close intracardiac septal defects. While coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is an example of cardiac surgery, congenital anomalies such as Tetralogy of Fallot and coarctation of the aorta are routinely managed through specialized corrective operations.43 However, access to cardiac surgery is often constrained, and most patients present late, or for the first time, with comorbid infections, severe malnutrition and impaired growth and development in LICs and LMICs.6

Heart transplantation

If medications or other treatment options cannot resolve the cardiac problem, a heart transplant may be the best option. The process known as a heart transplant involves removing a damaged heart and replacing it with a healthy donor heart.43

There are significant differences between LICs and LMICs and high-income countries (HICs) in terms of CHD prevalence, status and concerns. In HICs, most children with CHD are detected during antenatal screening, infancy or childhood. Over 90% of those born with CHD survive into maturity due to available intervention facilities. In most LMICs, CHD diagnosis relies on health systems and specialized personnel – which remain severely limited in the lowest-income regions.6

Mesenchymal stem cells as a promising strategy in congenital heart disease

Stem cells are unique cells defined by their capacity for unlimited self-renewal, their undifferentiated state and their ability to differentiate into multiple specialized cell types. These characteristics make them promising candidates for cell-based therapies aimed at treating degenerative conditions such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and beyond.46

Stem cells can be broadly divided into embryonic SCs (ESCs) and adult (somatic) SCs (ASCs). Based on their developmental potential, they are further classified into 4 categories. Totipotent SCs – such as the zygote – can give rise to all embryonic and extraembryonic tissues. Pluripotent SCs – including ESCs and iPSCs – are capable of differentiating into derivatives of the 3 germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm) but cannot form extraembryonic structures like the placenta or umbilical cord. Multipotent SCs – such as MSCs and hematopoietic SCs (HSCs) – can differentiate into a limited range of cell lineages, whereas unipotent SCs, like renal stem/progenitor cells (RSPCs), are restricted to producing a single specialized cell type while still retaining the capacity for self-renewal.47, 48

The ASCs consist of HSCs and MSCs. Furthermore, MSCs are commonly isolated from cord blood, peripheral blood, bone marrow, and fat tissue. When cultured, the cells will produce a cell line that morphologically resembles a fibroblast (fibroblast-like cell). In research, SCs can act as diagnostic cells where they can be applied to screen new drugs and test for cell damage due to viral infection.47

According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy, MSCs must meet 3 criteria: they must adhere to plastic under standard culture conditions; they must express CD105, CD73 and CD90 while lacking surface expression of CD45, CD34, CD14 (or CD11b), CD79α (or CD19), and HLA-DR; and they must demonstrate the capacity to differentiate in vitro into adipocytes, chondrocytes and osteoblasts.49

Friedenstein et al. were the first to isolate MSCs from mouse bone marrow, noting their fibroblast-like morphology and plastic adherence. Subsequent studies have identified MSCs in bone marrow as well as in umbilical cord blood, adipose tissue, peripheral blood, amniotic fluid, Wharton’s jelly, placenta, dental pulp, and dermis. Prior to experimental use, confluent MSC cultures – grown as a uniform monolayer – must be passaged to maintain optimal growth conditions.50

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy has been shown to improve cardiac function and reduce scar formation in patients with heart disease. These benefits are mediated primarily through enhancement of endogenous repair mechanisms, improving tissue perfusion, modulating the immune response, inhibiting fibrosis, and promoting proliferation of resident cardiac cells. In animal models, rare instances of MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes and vascular components have also been documented.51

Owing to their unique properties – including differentiation into cardiovascular lineages, immunomodulatory and antifibrotic effects, and the promotion of neovascularization – MSCs play a key role in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Autologous MSC transplantation has been shown to be safe in patients with cardiomyopathy, and allogeneic MSCs can likewise be administered with minimal immunogenicity.51

Despite these advancements demonstrating the potential of stem cell transplantation, neither preclinical nor clinical research has yet achieved complete cardiac recovery. To reach this goal, novel cell-based treatment strategies are required. Current research focuses on integrating MSCs with biomaterials, employing cell combinations, applying genetic modification, or preconditioning MSCs to enhance the secretion of paracrine factors such as growth factors, exosomes and microRNAs.48 Mesenchymal stem cells used for cardiomyocyte differentiation have been isolated from diverse sources, including Wharton’s jelly (umbilical cord), adipose tissue, bone marrow, endometrium, and even from olfactory bulbs of rats, mice, sheep, porcine species, and humans.17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 During growth factor-induced cardiomyogenic differentiation, MSC-specific markers decline while cardiac-specific markers are upregulated. Moreover, MSCs derived from umbilical cord tissue differentiate into cardiomyocytes more efficiently than those from bone marrow.52

Mesenchymal stem cells derived from Wharton’s jelly of the umbilical cord (UC-MSCs) represent a primary and practical cell source. Due to their noninvasive collection from abundant medical waste, ease of isolation and expansion, and high proliferative capacity, UC-MSCs are particularly suitable for LICs and LMICs.53, 54 Moreover, unlike ESCs, UC-MSCs are non-tumorigenic, exhibit low immunogenicity and pose minimal ethical concerns.55, 56

The application of SCs is promising in future regenerative medicine.46 The human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes can be used as diagnostic cells, heart disease models, for drug discovery, developmental biology, and regenerative medicine.57 Other type of stem cells such as iPSCs, ESCs and ASCs could be use as the source of cellular therapy in CHD. The use of iPSCs in cardiovascular disease has raised the risk of arrhythmogenesis, tumor growth and immune reaction rejection. Induced pluripotent SCs can differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro when exposed to growth factors such as VEGF, bFGF, TGF-β1, BMPs, or retinoic acid (RA).47 However, to develop into cardiomyocytes, iPSCs must be reprogrammed from somatic cells, which is costly and time-consuming.48

Stem cell-based therapies hold great promise for future regenerative medicine.46 Human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes can serve as diagnostic tools, in vitro disease models, platforms for drug discovery and developmental biology, and ultimately as regenerative treatments.58 In addition to iPSCs, ESCs and ASCs are valuable sources for cellular therapies in CHD. However, iPSC-based cardiovascular approaches carry risks of arrhythmogenesis, tumorigenicity and immune rejection. The iPSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes can be driven in vitro by growth factors such as VEGF, bFGF, TGF-β1, BMPs, or RA.59 Nevertheless, reprogramming somatic cells into iPSCs remains costly and time-consuming.55

Mesenchymal stem cells are a promising therapy for CHD because they are multipotent and can differentiate into various cell types, including cardiomyocytes. This capacity enables them to regenerate damaged cardiac tissue.60 Studies have shown that MSCs can reduce myocardial fibrosis and improve left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and endothelial function without increasing the risk of malignancy or arrhythmia. Furthermore, MSCs from multiple sources, such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, placenta, and umbilical cord, are suitable for allogeneic use.48 Mesenchymal stem cell therapy contributes to myocardial repair by promoting cardiomyocyte regeneration and has not been associated with adverse effects on myocardial integrity or tissue viability. Moreover, MSCs exert paracrine actions that enhance cardiac function and reduce scar burden, myocardial fibrosis and infarct size. Mesenchymal stem cells release a broad spectrum of bioactive mediators – such as cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, and microRNAs – that underpin their paracrine actions.51

They also exhibit anti-inflammatory properties, which can mitigate tissue injury resulting from chronic inflammation, a common feature of CHD. Furthermore, MSCs enhance angiogenesis by promoting new vessel formation, thereby improving blood supply to ischemic myocardium. In cell therapy applications, MSCs act as immunomodulators, regulating host immune responses to minimize the risk of graft rejection.52

Mesenchymal stem cells can ameliorate myocardial infarction by promoting angiogenesis and neovascularization, enhancing myocardial repair, inhibiting cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and replacing injured cardiomyocytes. Numerous phase I and II clinical trials have reported promising results for MSC-based regenerative therapies. Key factors in developing standardized MSC therapy protocols include selecting the optimal cell source, standardizing preparation procedures, determining the ideal dose and administration route, and ensuring reproducible clinical outcomes.

The results of phase III clinical trials are crucial for validating the therapeutic application of MSCs in cardiovascular medicine. Preconditioning techniques have enhanced engraftment, proliferation, differentiation, and survival of transplanted MSCs, thereby improving therapeutic efficacy.51

Signalling pathways regulating in vitro differentiation of MSCs into cardiomyocytes

Mesenchymal stem cells are self-renewing, multipotent progenitors capable of differentiating into cardiomyocytes as well as other mesodermal lineages. In vitro, MSC-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation can be driven by paracrine factors such as Wnt ligands, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and activation of Notch signaling.61, 62 According to Raman et al., signaling pathways such as HGF, PDGF and Notch regulate the differentiation of MSCs into cardiomyocytes.63

Cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) derive from cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) through migration, proliferation and differentiation processes that are stimulated by HGF secreted by MSCs. The Notch1 receptor and HGF/Met regulate the cell fate of CPCs. The Met tyrosine kinase receptor and HGF activation pathways lead to the induction of ERK1/2, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositide-3 kinase (PI3K/Akt) activities. In the early phases of cardiomyocyte maturation, HGF and Met receptors express transcription factors and structural genes such as Mef2C, TEF1-α, GATA-4, α-MHC, and desmin. Wnt receptors and the hepatocyte growth factor–immunoglobulin G (HGF–IgG) complex initiate biochemical signaling that drives epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and subsequent differentiation into cardiomyocytes.63, 64

The final stage of heart development, i.e., maturation, follows mesoderm formation and cardiac progenitor cell specification. Maturation is characterized by structural, transcriptomic, metabolic, and functional specialization of cardiomyocytes, enabling the heart to generate strong, efficient and enduring contractile force. Insulin-like growth factors regulate cardiomyocyte maturation via receptor tyrosine kinases, including the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) and the insulin receptor (INSR), which activate the PI3K–AKT and RAF–MEK–ERK signaling cascades.65

In vitro differentiation of MSCs into cardiomyocytes mimics in vivo cardiomyogenesis

Mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into cardiomyocytes only when specific signaling pathways are modulated and the requisite combination of growth factors, small molecules and extracellular matrix (ECM) components is present. Thus, these factors must be administered at defined concentrations and for precise durations to effectively drive differentiation.62

The differentiation of stem cells into cardiomyocytes in vitro is similar to the process of cardiomyogenesis in vivo. The mechanism starts from mesoderm induction, and then continues to cardiac progenitor cells or pre-cardiomyoblasts, immature cardiomyocytes or cardiomyoblasts, and mature cardiomyocytes.13, 66

Wnt, Activin, NODAL, and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signals impact early cardiomyogenesis. Several transcription factors have a role in early cardiomyogenesis, including Nkx2.5, GATA-4 and Tbx5. Other molecular cues, including Wnt pathway inhibitors and differentiation inducers such as fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and BMPs, play critical roles in cardiac specification and differentiation.67, 68 Differentiation towards the cardiac mesoderm lineage depends on the amount and timing of certain factors, such as BMP-4, TGF-β1, family member Nodal (or Activin A as a substitute of Nodal), and Wnt modulators.67, 68

During embryonic development, Wnt has a biphasic form, inhibiting cardiac induction at later stages and promoting cardiac gene expression at the early stage of mesoderm formation.69 Previous research showed that 5-Aza and Sal-B can improve early mesodermal commitment by increasing Wnt/β signaling.70, 71 Even though Wnt plays a role in differentiation to early cardiomyocyte, the latest study has shown that adding Wnt inhibitors (such as IWR-1, IWP-3 or XAV939) enhanced cell differentiation in the late-phase of differentiation to the cardiac progenitor cell stage.22 The administration of neuregulin, fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF-1), IGF-1, and periostin peptide can be used to promote postnatal cardiomyocyte cycling or late-stage cardiomyocyte.72

Under defined in vitro conditions, MSCs can differentiate into mesodermal cell types, including cardiomyocytes, when exposed to tailored “cocktails” of small molecules and growth factors that precisely direct lineage specification. For example, a defined cocktail of factors, including bFGF, Sal-B, TGF-β1, BMP-2, 5-Aza, NRG-1, forskolin, and Ang-II, induces MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes.17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 The expression of cardiomyocyte-specific genes and proteins is evidence for in vitro differentiation. Soluble chemical factors in the culture medium initiate signaling cascades that regulate cell differentiation.

Chemical inducer for in vitro differentiation of MSCs into cardiomyocytes

5-azacytidine

5-azacytidine is commonly used to induce MSCs to differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro. It can also be used in stem cell laboratories in LMICs. 5-azacytidine is a cytidine nucleoside analog and DNA demethylating agent primarily used to induce MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes in vitro. It inhibits DNA methyltransferases, thereby modulating chromatin structure, gene expression and processes such as X-chromosome inactivation. A potent inhibitor of DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferases (DNMTs), 5-Aza promotes DNA demethylation and activates cardiac gene expression.21 The concentration of 5-Aza used to induce MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes is typically 10 μmol/L for 24 h, resulting in upregulation of cardiac markers such as Cx43 and cTnT.15, 18, 23, 25, 31

Further research showed that 5-Aza administration in human UC-MSCs induced the activation of extracellular signal-related kinases (ERK) but did not affect protein kinase C. A particular ERK inhibitor, U0126, can potentially prevent human UC-MSCs from expressing cardiac-specific proteins and genes when 5-Aza is present. These findings indicate that persistent activation of the ERK pathway by 5-Aza induces in vitro differentiation of human UC-MSCs into cardiomyocytes.73 Differentiation of cardio-sphere-derived cells (CDCs) into cardiomyogenic cells can be induced with 5-Aza by upregulating cardiac-specific genes like Nkx2.5, α-sarcomeric actin and GATA-4. The phosphorylation of β-catenin is negatively regulated by the Wnt pathway.69

During development, the pathway of Wnt/β-catenin-dependent controls important elements of polarity, migration, organogenesis, and patterning. Similarly, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is crucial for the maturation of cardiomyocyte-derived MSCs. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling can stimulate the mouse bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) to differentiate into cardiomyocytes and upregulate the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs). Nevertheless, 5-Aza significantly upregulates glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), thereby modulating cardiogenesis.61

Neuregulin-1

Neuregulin-1 is an epidermal growth factor (EGF) that promotes proliferation, differentiation and survival in several tissues, such as breast epithelial cells, glial cells, neurons, and myocytes. A group of tyrosine kinase receptors (ErbB2, ErbB3 and ErbB4) exerts its biological effects by dimerizing upon ligand binding, which results in phosphorylation and subsequent signaling. NRG-1/ErbB signaling is most recognized for its critical function in developing neurons and the embryonic and adult heart.74, 75

Neuregulin-1 promotes the development and survival of embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and directs their differentiation into cardiac conduction system cells. When the endocardial endothelium produces NRG-1, the surrounding cardiomyocytes express ErbB2 and ErbB4 in the embryonic heart. On the other hand, aside from its function in ventricular trabeculation and cardiac cushion creation, the ErbB3 receptor is not expressed in the endocardium or the myocardium.74

In the adult heart, NRG-1 is expressed by cardiac endothelial cells adjacent to cardiomyocytes, specifically within the endocardium and myocardial microvasculature, whereas cardiomyocytes express ErbB2 and ErbB4 receptors but lack ErbB3. Angiotensin II and epinephrine raise blood pressure and inhibit endothelial production, while endothelin-1 and mechanical strain promote it. Neuregulin-1 binds to ErbB4 receptors on cardiomyocytes, inducing either ErbB4 homodimerization or ErbB4/ErbB2 heterodimerization. This receptor dimerization activates the Akt and ERK signaling pathways, resulting in growth-promoting and cytoprotective effects. Moreover, cooperative signaling between M2 muscarinic receptors and activation of cardiomyocyte nitric oxide synthase (NOS) modulates cardiac contractility and adrenergic responsiveness.74

Basic fibroblast growth factor, NRG-1 and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) regulate signaling pathways that direct myocardial cell specification. In ESCs, these factors stimulate cardiac-specific transcription factors such as GATA4 and Nkx2.5. Neuregulin-1, bFGF and forskolin have been implicated in regulating cardiac cell-fate determination and heart development. These factors influence both cardiomyocyte differentiation and the cardiac microenvironment. Since all growth factors were applied simultaneously, the relative contribution of each component to myocardial specification remains unclear. For MSC induction into cardiomyocytes, NRG-1 is administered at 50 ng/mL (1.92 × 10–6 M).24

Forskolin

Forskolin, a cell-permeable diterpenoid, activates adenylate cyclase and protein kinase A, thereby elevating intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels. It possesses antihypertensive and positive inotropic effects. The forskolin-induced response in embryonic cardiomyocytes indicates a functional cAMP signaling pathway. Moreover, forskolin modulates calcium transport and currents and stimulates adrenergic receptors in culture, leading to hypertrophic responses. It increases the expression of cardiomyocyte markers, cTnT and myocyte enhancer factor 2C (Mef2c), while suppressing mesodermal and cardiac progenitor markers.76, 77 Forskolin treatment enhances the beating frequency of cardiomyocytes. Forskolin is administered at a concentration of 10 mM to induce MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes.24

Basic fibroblast growth factor

The bFGF is required for the initial development of the embryo, especially to maintain mesoderm lineages during cardiac organogenesis. It is a potent mitogen that controls stem cell migration, differentiation, proliferation, and survival. The bFGF promotes the ESCs to differentiate into early maturation cardiomyocytes and expresses cardiac markers of α-cardiac myosin heavy chain (MHC) and β-MHC. These findings suggest that bFGF must act synergistically with additional factors to drive MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes. Basic fibroblast growth factor also enhances the migration capacity of MSCs by activating the Akt signaling pathway.21, 78, 79 The concentrations of bFGF used to induce MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes are 10 ng/mL and 20 ng/mL when applied in combination with other factors.24, 32

The bFGF is expressed in cardiac progenitor cells; it plays an important role in early cardiomyogenesis and directly influences cardiomyocyte formation. Before downregulating the early phase of vertebrate cardiac development in vivo, bFGF is involved in the autoregulatory mechanisms of cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation. During the tubular stage of cardiogenesis, bFGF and FGF receptor-mediated signaling govern cardiomyocyte formation. However, beyond the 2nd week of embryogenesis, myocyte development becomes independent of bFGF.79

Transforming growth factor-β1

Transforming growth factor-β1 is a pleiotropic cytokine that regulates multiple aspects of cellular and tissue physiology. The TGF-β1 is a cytokine with several functions that influence the survival, proliferation and differentiation of several kinds of cells.19 The development of the ventricular myocardium and the formation of the coronary vasculature during embryogenesis are influenced by TGF.21 Previous studies have shown that TGF-β1 can drive the differentiation of BM-MSCs and ESCs into cardiomyocytes, and that TGF-β1 is essential for embryonic heart development.80

TGF-β1 is more effective in expressing α-actin, Cx43, MHC, and cTnI when combined with other factors like 5-Aza. Additionally, TGF-β1 and Sal-B increase the expression of cardiac markers like GATA-4 and Nkx2.5 compared to either factor alone. The dose of TGF-β1 for inducing rat BM-MSCs to cardiomyocytes is 5 ng/mL and 10 ng/mL.19, 31 Rat BM-MSCs exhibited significantly increased mRNA expression of Cx43, myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C), α-actinin 2 (ACTN2) and cardiac troponin T (TNNT2) in response to TGF-β1, electrical stimulation (ES) and combined TGF-β1 + ES treatments compared with control.36

Bone morphogenetic protein 2

The BMP superfamily has gained significant attention since the discovery in 1988 that BMP-2 potently induces bone and cartilage formation in vertebrate skeletal biology.81 Undifferentiated MSCs are converted into chondrocytes and osteoblasts as well as osteoprogenitors into osteoblasts through the action of the BMP. The use of BMP-2 therapy is to improve cardiomyocyte contractility and prevent cell death, leading to significant implications for treating myocardial ischemia.17, 33 Therefore, in LMICs, BMP could be a growth factor that induces MSCs to differentiate into cardiomyocytes.

Mesenchymal cells from bone marrow can be converted into cardiomyocytes using BMP-2. According to Lv et al., Sal-B combined with BMP-2 at 250 mg/L and 200 ng/L, respectively, enhanced cardiomyocyte differentiation compared to single treatments.33 Conversely, Hou et al. showed that the combination of 10 μg/L BMP-2 and 10 μmol/L 5-Aza significantly increased the rate of cardiac differentiation and showed reduced effects on cell damage.17

BMP-2 has shown therapeutic promise in treating myocardial disease by preventing the death of cells and enhancing cardiomyocyte contractility. It promoted the phosphorylation of the Smad1/5/8 protein, which saved adult cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress and long-term hypoxia-induced cell damage without activating the cardiodepressant TGF-β pathway.82

A previous study documented that after being treated with BMP-2, BM-MSCs showed enhanced differentiation to cardiomyocytes by identifying cardiomyocyte-specific protein expression, ultrastructural characterization and transcription factor mRNA expression. Additionally, Sal-B, extracted from Salvia miltiorrhiza, when combined with BMP-2, may enhance the efficiency of cardiomyocyte differentiation.33

Angiotensin II

Angiotensin II is a bioactive substance present in myocardial cell lysate and has many biological effects in addition to aiding in the development of the myocardium microenvironment. Angiotensin I is transformed by the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) into Ang-II, activating Ang-II receptors to modulate various cardiovascular responses, such as vasoconstriction and heart growth.83

The dose of Ang-II is 0.2 mg/mL or 0.2 mmol/L and 0.1 mmol/L is used to induce MSCs in cardiomyocytes for 24 h.23, 32 Angiotensinogen is formed by the liver and transformed into angiotensin I and II. The action of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) can be initiated by Ang-II binding to the angiotensin II receptor type 1 and type 2 (AT1R and AT2R), or it can be further degraded or altered to produce the cardioprotective peptides angiotensin, angiotensin IV and alamandine, which operate by binding to Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor member D (MrgD), AT4R and MasR receptors, respectively. N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SKDP), apelin and angioprotectin have been discovered as novel cardioprotective RAS peptides. As a result, the RAS can have both pathogenic and cardioprotective effects on the heart, with the relative importance of each defining the cardiovascular system’s overall impact. The interaction of Ang-II with AT1R results in the activation of numerous intracellular signaling pathways, including MAPK, β-arrestin, G protein-independent, JAK/STAT, protein kinase C (PKC), scaffold proteins, numerous tyrosine kinases, and the transactivation of growth factor receptors.84

Salvianolic acid B

Salvianolic acid B is a water-soluble phenolic compound isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza, a traditional Chinese medicinal herb used for centuries to treat various cardiac disorders. It has been shown to inhibit apoptosis induced by combined hyperglycemia and hypoxia in cardiomyocytes derived from ASCs. Lv et. al. described that Sal-B inhibited apoptosis by reducing the levels Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF1α) and cleaved caspase 3. Salvianolic acid B has been proven in trials to stimulate human MSCs’ osteogenesis without cytotoxicity, making it a viable therapeutic agent for the treatment of osteoporosis.33

Shu et. al. explained that Sal-B protects iPSC-derived neuron SCs (NSCs) exposed to H2O2, while Gao et al. suggested that Sal-B enhances the ability of BM-MSCs to differentiate into type I alveolar epithelial cells.85, 86 According to the study by Lv et al., MSCs treated with Sal-B and TGF-β1 expressed higher levels of cardiac-specific markers – including Nkx2.5, GATA-4 and cTnI – compared with the control group. TGF-β1 and Sal-B can be used effectively to reduce apoptosis. In the study by Lv et al., Sal-B demonstrated cardioprotective effects in acute myocardial infarction, making it a potentially valuable therapeutic adjunct. Their western blot analyses of proteins related to autophagy, apoptosis and angiogenesis further supported the cardioprotective role of Sal-B. Owing to these properties, Sal-B represents a relatively safe and promising trigger for cardioprotection.19

Lv et al. and Chan et al. found that Sal-B alone had minimal impact. However, when Sal-B is combined with TGF-β1 or vitamin C, it can promote MSCs or other SCs to differentiate into cardiomyocytes and increase the expression of cardiomyocyte maturation markers in a dose-dependent manner. The switch between neurogenesis and cardiomyogenesis in SC differentiation can be regulated by p38 MAP kinase activity. The dose of Sal-B to induce differentiation to cardiomyocytes is 250 mg/L for 72 h.33, 87 Salvianolic acid B also increased the expression of Wnt signaling proteins while reducing the expression of transcription factors associated with the Notch signaling pathway.71

Insulin-like growth factor

Insulin-like growth factor 1 is a 70-amino-acid, single-chain protein critical for cardiomyocyte development. It inhibits apoptosis and necrosis while promoting the growth, proliferation and differentiation of diverse cell types, both in vivo and in vitro, including vascular smooth muscle cells and cardiomyocytes. Upon binding to its receptor, the IGF1R, IGF-1 engages the receptor’s intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, triggering downstream signaling cascades such as the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways.88

In co-cultured myocardium and BM-MSCs, HGF and IGF-1 stimulated the cardiac-specific transcription factor GATA4 expression, representing myocardial differentiation.89 Insulin-like growth factors can be essential for LICs because they play a significant role in stem cell biology, which can either improve differentiation or enhance proliferation and self-renewal.90

Other treatment for in vitro differentiation MSCs to cardiomyocyte

Even though there are numerous methods for inducing MSCs to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, the results of differentiation in 2D culture might occasionally be insufficient, immature and unpure.62 In addition to supplementary growth factors, several adjunctive strategies – such as ES, controlled hypoxia, co-culture with cardiomyocytes, and 3D approaches using hydrogels or scaffolds – are employed to enhance the efficiency of MSC-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation (Figure 2).

Co-culture of cells

Co-culture involves growing MSCs with other cell types to promote intercellular communication through direct cell–cell interaction, paracrine signaling and soluble molecules.91 Previous research showed that MSCs co-cultured with cardiomyocytes can differentiate into these cells. It is suggested that one of the factors influencing the differentiation of MSCs into cardiomyocytes is direct cell-to-cell contact. The co-culture technique enables research into physical and paracrine variables influencing cardiac cell fate and differentiation.24

Co-culturing MSCs with cardiomyocytes in vitro produced direct contact between both types of cells. They formed gap junctions, which reverse-facilitated the low-resistance transmission of electrical and chemical signals between neighboring cells, a process linked to cardiomyogenic differentiation. Co-culturing MSCs with cardiomyocytes also promoted MSC expression cardiac-specific markers, like Cx43, Nkx2.5, GATA-4, sarcomeric α-actin, MHC, cTnI, and atrial natriuretic peptide, because the adult heart tissue environment expresses the right signals that encourage SCs to differentiate into cardiomyocytes. Co-culture MSCs with neonatal cardiomyocytes and the addition of growth factors such as neuregulin, forskolin and bFGF can differentiate into cardiomyocytes and show synchronous contractions.24, 92

Electrical stimulation

An essential component of the cardiomyocyte microenvironment is the electrical milieu: in vitro, this is created by connecting the culture well plate to electrodes and applying voltage across the medium. According to He et al., ES can promote SC differentiation toward both cardiogenic and neurogenic lineages. Electrical stimulation enhances the expression of cardiac transcription factors Nkx2.5 and GATA4, which are critical during early myocardial development. In rat BM-MSCs, ES promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation by upregulating TGF-β1 and increasing the expression of Cx43 and α-sarcomeric actinin.36

Scaffold

The cell requires a scaffold that provides rigidity and biological support to differentiate into cardiomyocytes. A combination of cells, scaffolds and growth factors can regulate cellular activity and cell differentiation.93 Scaffolds are essential in tissue engineering because they can support and provide resilience to SCs by creating an appropriate microenvironment that aids cell transplantation and regeneration.8 Biological scaffolds facilitate the growth, development and implantation of SCs in injured cardiac tissue. The scaffold can be applied in LICs and LMICs due to its potential advantages. This increases the efficacy of stem SC-based therapies and makes them more widely available and reasonably priced.94

Graphene oxide (GO)-based scaffolds reported as innovative scaffolds to enhance the in vitro differentiation capacity of human UC-MSCs. Graphene oxide may engage cellular mechanotransduction pathways and modulate how cells respond to external stimuli. Derivatives of graphene may be used as cell mechanical stimulation inducers to improve the efficiency of angiogenic and cardiogenic differentiation in human UC-MSCs.34

During the differentiation of MSCs into cardiomyocytes, the specific marker proteins are expressed in the cell membrane. Mesenchymal stem cells are positive for CD90, CD73 and CD105, and negative for CD34 and CD45.95 Thus, a specific cell surface marker on BM-MSCs can identify their cardiomyogenic differentiation. Spontaneous contractions combined with expression of cardiomyocyte-specific markers confirm MSC differentiation into functional cardiomyocytes. Cardiac-specific markers encompass transcription factors (Nkx2.5 and GATA4), gap-junction protein Cx43, MEF2C, sarcomeric proteins (α-MHC, titin, desmin, α-cardiac actin), and cardiac peptides such as ANP, cTnI and cTnT.17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37

Discussion

Mesenchymal stem cells have emerged as a promising option for regenerating injured cardiac tissue, garnering increasing attention in recent years.96 In CHD, MSCs offer new therapeutic possibilities. In this review, we comprehensively analyzed growth factors, with particular emphasis on individual factors and their combinations, that can trigger MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes. Moreover, we propose a streamlined, scaffold-based in vitro protocol to enhance MSC-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation, tailored for stem cell laboratories in LMICs.

Mesenchymal stem cells derived from diverse sources, including the olfactory bulb, endometrium, adipose tissue, Wharton’s jelly of the umbilical cord, and bone marrow, can differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro. The MSC-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation is induced by administering specific growth factors and small molecules, such as RA, 5-Aza, Ang-II, bFGF, Sal-B, TGF-β1, BMP-2, forskolin, and NRG-1.17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 Various induction “cocktails” have been evaluated for MSC-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation, including: 5-Aza with TGF-β1; 5-Aza with BMP-2; Sal-B with BMP-2; bFGF, forskolin and NRG-1; TGF-β1 with Sal-B, TGF-β1 combined with bFGF, IGF-1 and VEGF; TGF-β1 with ES; and 5-Aza with Ang-II and TGF-β1.

All the studies mentioned above17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 indicate that using cocktails to differentiate MSCs into cardiomyocytes can improve cardiomyocyte marker expression compared to single factors. The efficiency of differentiation can be verified using qualitative data from immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry (IHC). Hou et al. found that BMP-2 and 5-Aza induced BM-MSC differentiation with an efficiency of 27.97 ±1.77%.17 According to Lv et al., 5-Aza had an approx. 30% success rate in converting MSCs into cardiomyocytes.19 Li et al. identified that the percentage of cTnT-positive cells, one of the cardiomyocyte markers, was approx. 46.3 ±2.1%.18

The mechanism that enables SCs to differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro is similar to the process of in vivo cardiogenesis, with the mesoderm being the initial target, followed by cardiac progenitor cells or pre-cardiomyoblasts, immature cardiomyocytes or cardiomyoblasts, and mature cardiomyocytes. GATA-4, MEF-2C, Nkx2.5, MHC, Cx43, cTnT, cTnI, α-actin, and desmin are frequently used cardiomyocyte markers. Nkx2.5, GATA4, Tbx5, Islet-1 (Isl-1), and myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) serve as markers of cardiac progenitor cells. Nkx2.5 and Tbx5/20 remain expressed by immature cardiomyocytes or cardiomyoblasts, along with myosin heavy chain (MYH), GATA-4 and Hand 1/2. Mature cardiomyocytes express markers such as cTnT, α-sarcomeric actinin, myosin light chain 2a (MLC2a), myosin light chain 2v (MLC2v), sodium channel subunit SCN5A, L-type calcium channel subunit CACNA1C, cardiac myosin heavy chain (cMHC), and Iroquois homeobox 4 (IRX4).13, 66

A streamlined differentiation protocol minimizes the number of reagents needed to modulate each signaling pathway and prioritizes readily available chemicals, which is especially advantageous in LMIC settings. We propose a streamlined, stage-specific protocol for MSC-to-cardiomyocyte differentiation: first, induce cardiac mesoderm with 5-Aza; next, specify cardiac progenitor cells via Wnt pathway inhibition; and finally, drive cardiomyocyte maturation using IGF-1.

Huang et al. reported that MSCs co-cultured with rat neonatal cardiomyocytes in an induction medium supplemented with bFGF, forskolin and neuregulin exhibited spontaneous beating, demonstrating functional cardiomyocyte differentiation. Spontaneous contractions were also observed by Zhao et al. in MSCs treated with the Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 in MethoCult medium.24, 37

The cardiomyocyte differentiation protocol is suitable for laboratories or research centers with minimal facilities. Therefore, using fewer reagents that target key signaling pathways at each stage of differentiation is preferable. Employing readily available chemicals in LMICs and minimizing the use of additional techniques, such as selecting either scaffolds or 3D culture alone, offers a more practical and accessible approach.97, 98

In monolayer, or two-dimensional (2D) culture systems, cell–cell interactions are confined to a single substrate layer during cardiomyocyte differentiation. The 2D approach is cost-effective and permits straightforward manipulation and precise arrangement of the culture. On the other hand, limitations include low throughput, reduced contact connections between cells and the ECM, and the absence of soluble growth agents. However, three-dimensional (3D) culture using a scaffold enhances cell proliferation and enables the ECM to recapitulate the native tissue microenvironment.97, 98

In vitro, 3D cultures closely resemble the function of a miniature organ, with cells adhering tightly to one another and forming connections that facilitate signal transmission.99 Developing 3D cultures is one of the techniques for promoting the maturation stage of cardiomyocytes derived from SCs.100

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. First, recent publications on MSC differentiation into cardiomyocytes are scarce, as research emphasis has shifted toward pluripotent SC applications. Second, many studies focus on advanced in vitro and in vivo models that may not translate easily to LIC/LMIC settings. Nevertheless, we believe this review provides a valuable foundation for future efforts to harness multipotent SCs in cardiovascular therapy, particularly for CHD. We also anticipate that forthcoming experiments will emphasize protocols and technologies accessible in LMICs and LLMICs.

Conclusions

Differentiation of MSCs into cardiomyocytes remains a key challenge in LICs and LMICs. Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs from the umbilical cord are particularly advantageous in these settings due to their noninvasive collection from abundant medical waste, ease of isolation and expansion, and high proliferative capacity. A straightforward, resource-efficient protocol for sequential cardiomyocyte differentiation involves inducing cardiac mesoderm with 5-Aza or BMP, followed by cardiac progenitor specification through Wnt pathway inhibition, and concluding with cardiomyocyte maturation promoted by IGFs. Finally, employing a 3D scaffold supports cell attachment and alignment and represents the most accessible technique for laboratories with limited infrastructure.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.