Abstract

Background. Research on the psychological distress experienced by women with benign breast disease (BBD) remains limited, though some evidence suggests it may resemble that of women with breast cancer (BC).

Objectives. This study aimed to use the Distress Thermometer (DT) to assess the levels of psychological distress and identify influencing factors during the diagnostic phase in patients with BC and BBD.

Materials and methods. From October 2022 to May 2023, a questionnaire survey incorporating the DT and Problem List (PL) was conducted among inpatients in the diagnostic phase for BC or BBD at the Breast Surgery Department of Shanxi Bethune Hospital (Taiyuan, China). Statistical analysis, including descriptive and inferential methods, was performed to examine factors affecting psychological distress in patients with BBD and BC.

Results. In this study, 373 participants were evaluated for psychological distress during the diagnostic phase. Among 255 patients diagnosed with BBD, the median distress score was 4, with a distress prevalence of 52%. The primary sources of distress included anxiety (43.5%), fear (21.2%), pain (7.1%), sleep disturbances (6.7%), and childcare responsibilities (5.1%). Among 118 BC patients, the median distress score was slightly higher at 4.5, with a distress prevalence of 63.6%. Key distress factors were anxiety (47.5%), fear (33.1%), financial worries (21.2%), depression (18.6%), and sadness (15.3%). Key predictors of distress varied between the 2 groups. For patients diagnosed with BBD, younger age, lower education levels, unemployment, and a higher Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®) classification significantly contributed to higher distress levels. In patients diagnosed with BC, younger age, lower education levels, and unemployment were the primary risk factors.

Conclusions. These findings underscore the psychological burden faced by both patient groups during diagnosis, highlighting the need for early identification and management of distress in this population.

Key words: psychological distress, breast cancer (BC), benign breast disease (BBD), distress thermometer (DT), predictors of distress

Background

Breast diseases are classified into benign breast disease (BBD) and malignant breast cancer (BC), with BBD accounting for approx. 75% of breast biopsy diagnoses.1 A screening study of over 70,000 women reported a 44.7% prevalence of BBD.2 Despite being less frequent, BC remains one of the most prevalent malignancies affecting women, with 2.3 million new cases reported globally in 2022.3 In China, the incidence of BC has been increasing by 3% annually, with more younger women being diagnosed.4

Breast cancer patients often face significant psychological challenges due to changes in body function and appearance throughout diagnosis, treatment, and recovery.5 High levels of psychological distress can lower their quality of life, reduce treatment adherence, and even increase the risk of suicidal behavior.6 Research indicates that nearly half of women with BC experience distress, particularly around the time of diagnosis.7, 8 Even before a confirmed diagnosis, the uncertainty of potential cancer can heighten anxiety.9

While BC has high incidence and mortality rates, most palpable breast masses and lesions are benign, with a large portion of women presenting with breast complaints ultimately diagnosed with BBD.10 Benign breast disease is common and comprises various histological subtypes characterized by changes in breast tissue. Unlike cancer, BBD is nonmalignant and not life-threatening, though some cases may progress to BC.11 Studies have highlighted elevated psychological issues among women with BBD, occurring before, during, and even after the diagnostic phase.12, 13, 14 This significant psychological burden is partly driven by prognostic uncertainty and the perceived risk of developing BC.15 However, while most research has focused on distress in BC patients, few studies have examined psychological distress in those with BBD. This gap in knowledge makes it unclear whether the distress experienced by BBD patients is similar to that of BC patients, especially during the diagnostic phase.

Objectives

This study aimed to compare psychological distress levels in women diagnosed with BBD and BC during the diagnostic phase using the Distress Thermometer (DT), a validated, simple, and quick screening tool for distress. We further sought to identify the primary distress factors and predictors in each group, with the goal of informing early psychological support strategies for all women facing a breast disease diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This study is a cross-sectional investigation that took place between October 2022 and May 2023, with participants being recruited from the inpatient Breast Surgery Department of Shanxi Bethune Hospital. The reporting of the study was based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for the sake of transparency in research reporting.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients aged 18 years or older; breast ultrasound and/or mammography indicating a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®) category 3 or higher; full insight into their health status; and the ability to read and write independently or with assistance from medical personnel to complete the questionnaire.

The exclusion criteria were communication barriers due to cognitive impairment or mental health disorder and a previous diagnosis of BC or other malignant neoplasms. Sample sizes were determined through power analysis to ensure statistical confidence, requiring a minimum of 327 participants for a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. Anticipating a 10% non-response rate, the minimum target was set at 360 participants. This study achieved the goal, enrolling 373 participants to enable adequate statistical analysis.

The instrument: Distress Thermometer

The DT is designed to measure 1 aspect of psychological distress. It includes a visual analog single-item scale, that ranges from 0 (no distress) to 10 (mid-extreme distress). The higher the score, the greater the distress experienced. A previously established cut-off score of 4 indicates moderate-to-severe distress, suggesting a need for additional psychological support.16 The DT has been widely used in oncology and other medical settings and has demonstrated strong reliability and validity across diverse populations, including Chinese patients.

The Problem List (PL) is a 42-item questionnaire that determines if patients have had any problems in the last week and what issues, if any, might be causing them distress. The items are structured into 5 categories: triaging problems (practical) with 12 items, emotional issues with 9 items, social difficulties with 6 items, religious/spiritual issues with 6 items, and physical problems with 9 items. Participants were asked to state if the problem had occurred in the past week by responding with a simple “yes” or “no” on the list. The PL has been culturally adapted and validated in different settings, including Chinese BC patients, where it had good test-retest reliability.

Data collection

Demographic information for all study participants was gathered using a structured questionnaire, which included age, education level, employment status, reproductive history, marital status, and type of medical insurance. Additionally, disease-related information was collected, including breast BI-RADS classification, clinical diagnoses, comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and thyroid disorders, as well as a family history of BC and other tumors.

The inclusion of these demographic and clinical variables was based on prior research indicating their potential influence on psychological distress. For example, employment status and education level may affect coping strategies and access to healthcare, while BI-RADS classification directly reflects the severity of suspected disease and may heighten distress.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate means, medians, frequencies, percentages, and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for patient characteristics, distress levels, and reported problems. The normality of continuous variables, such as age, was assessed separately for the BBD and BC groups using the Shapiro–Wilk test (Supplementary Table 1). In both groups, the test indicated non-normal distributions (p < 0.001). However, due to the sufficiently large sample sizes in each group (n > 30), the Central Limit Theorem supports the use of parametric tests, such as the t-test, and allows for the reporting of means and standard deviations (SD). Therefore, although age was not normally distributed, the use of parametric methods remains statistically justifiable in this context. Distress Thermometer scores were categorized into 2 levels: scores of 0–3 indicated mild distress, while scores of 4–10 indicated moderate-to-severe distress. Anxiety (A) scores and Depression (D) scores were also recorded. The χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests were employed to compare distress levels across groups with and without specific problems. Additionally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors significantly associated with distress, ensuring that predictor selection was based on clinical relevance and prior research. To verify logistic regression assumptions, linearity in the logit was tested using the Box–Tidwell procedure, showing a non-significant interaction term (p > 0.05), confirming linearity. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values remained below 2, indicating no multicollinearity. Model adequacy was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (χ2 = 6.73, p = 0.57), confirming an acceptable fit (Supplementary Table 2). The Nagelkerke R2 was higher in the BC group, indicating that the model accounted for a greater proportion of the variance in distress levels among BC patients compared to BBD patients (Table 1, Table 2). All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA), with a p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Ethics

This study complies with the ethical standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanxi Bethune Hospital (Taiyuan, China; approval No. YXLL-2023-093), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring that they fully understood the study’s purpose, procedures, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequences.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 379 patients were surveyed, with 6 excluded due to incomplete clinical data (4 cases) and non-compliant diagnostic specimens (2 cases), resulting in a final sample of 373 participants. Among them, 255 patients were in the BBD group, and 118 were in the BC group. The age range for the BBD group was 14 –69 years, with a mean age of 40 ±11 years, while the BC group ranged from 27 to 83 years, with a mean age of 53 ±12 years. The BC group was significantly older than the BBD group (p < 0.01). Additionally, compared with the BC group, the BBD group had a significantly higher proportion of unmarried individuals (p < 0.01), fewer comorbidities (p < 0.01), and a greater proportion of nulliparous women (p = 0.021) (Table 3).

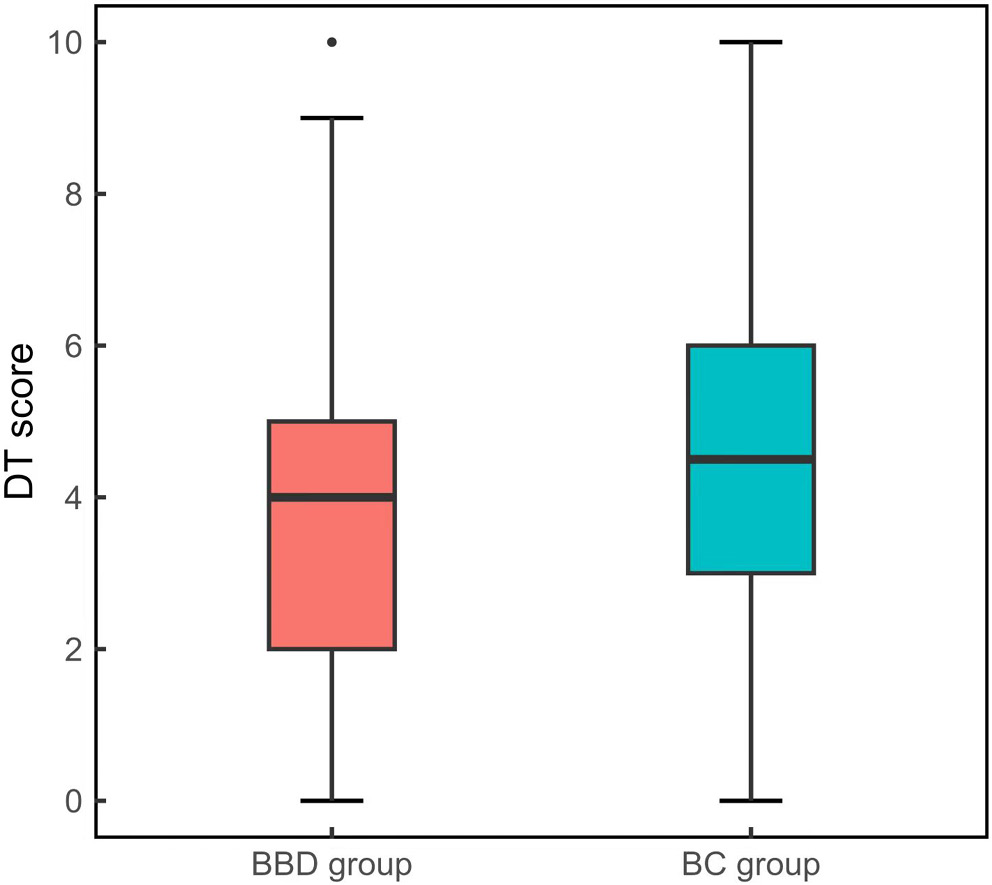

Comparison of psychological distress between women with benign breast disease and breast cancer

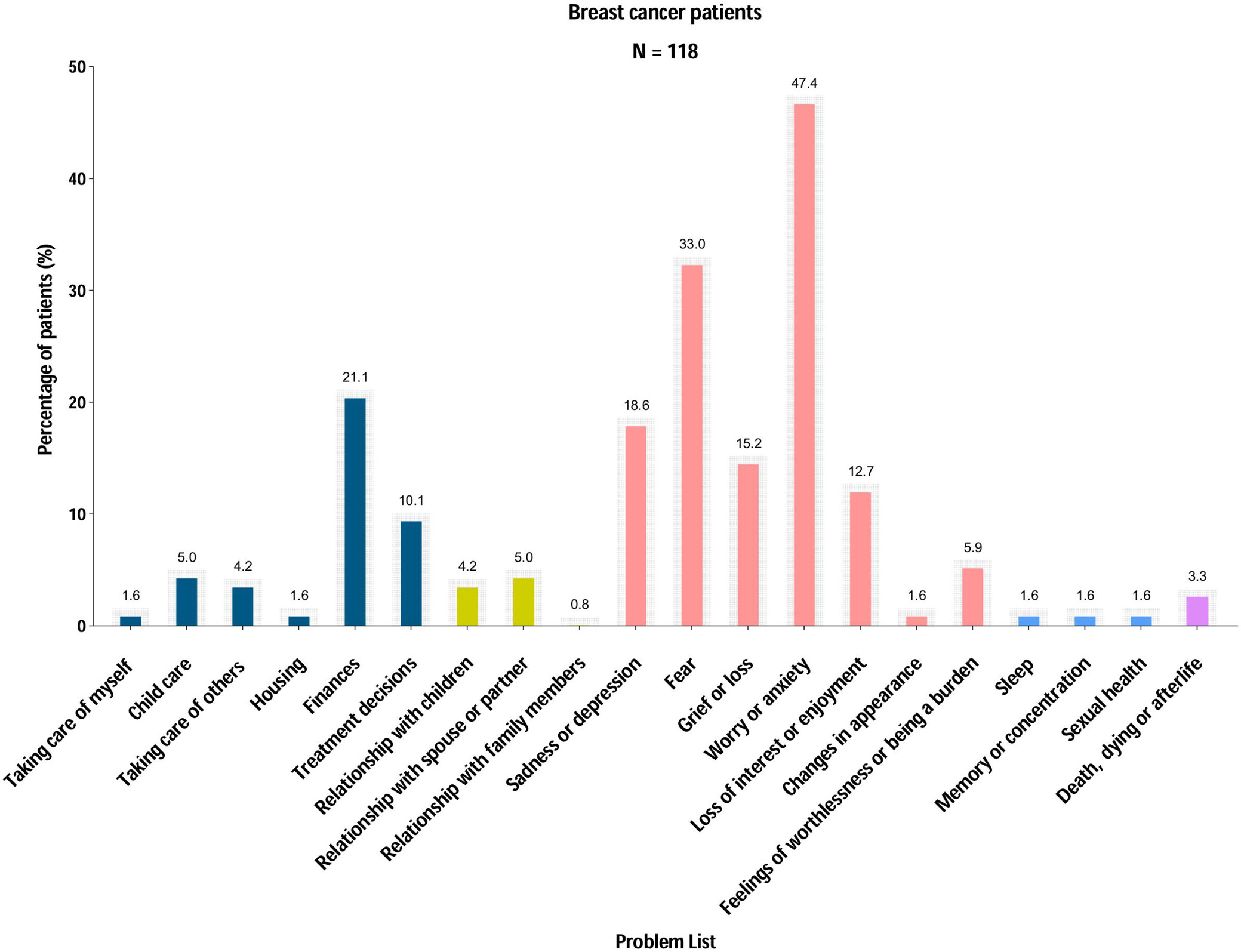

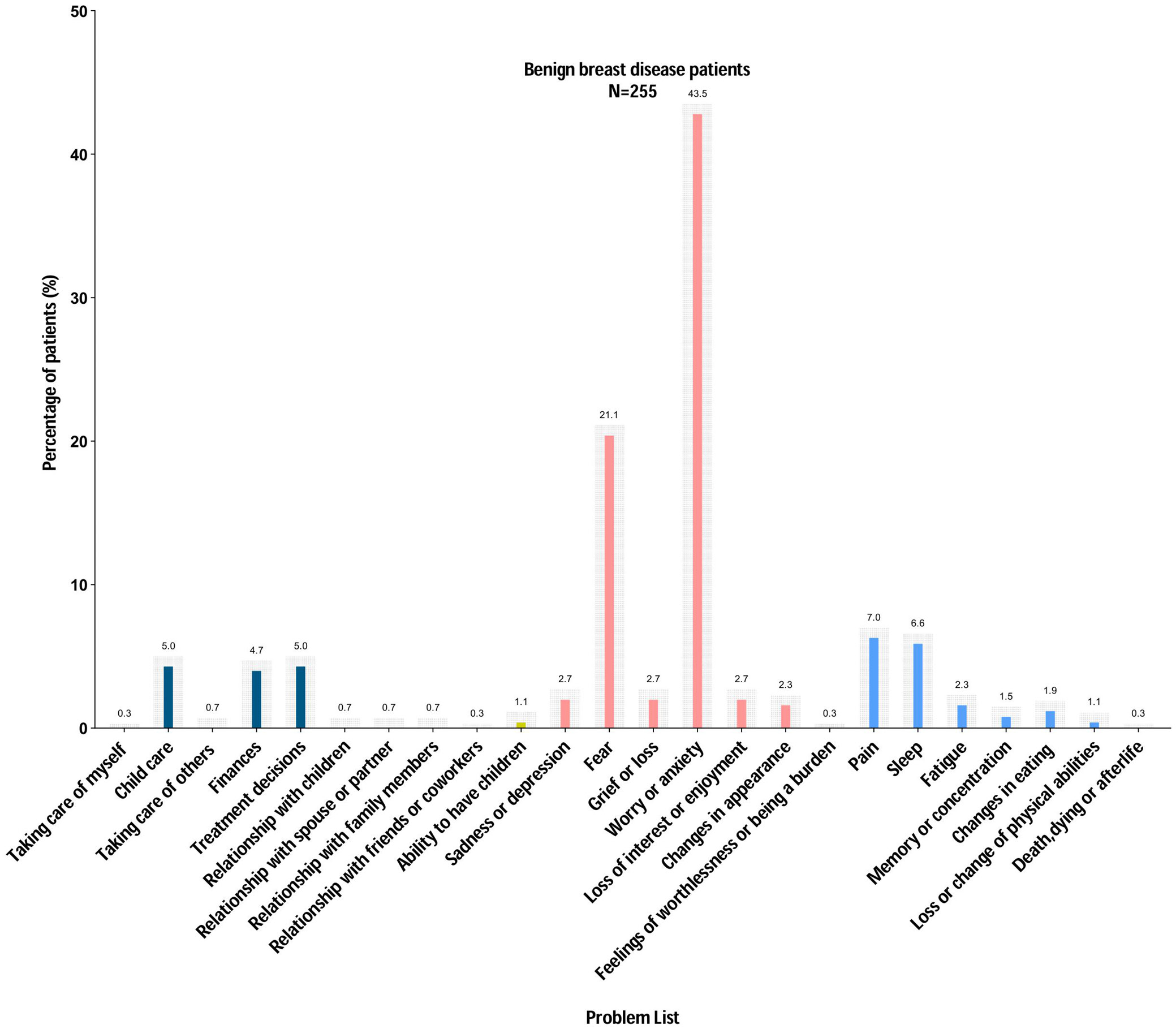

Psychological distress was assessed using the DT, with a score of ≥4 indicating clinically significant distress. In the BC group, 63.6% of women reported psychological distress (score ≥ 4), with a median distress score of 4.5 (IQR = 3–6). In the BBD group, 52.2% of patients reported distress, with a median score of 4 (IQR = 2–5). Overall, psychological distress levels were higher in the BC group than in the BBD group (Figure 1). The most frequently reported causes of psychological distress differed between the 2 groups. In the BC group, the main causes were worry or anxiety (47.4%), fear (33.0%), financial concerns (21.1%), sadness or depression (18.6%), and feelings of sorrow or loss (15.2%) (Figure 2). In the BBD group, they were worry or anxiety (43.5%), fear (21.1%), pain (7.0%), sleep difficulties (6.6%), and childcare challenges (5.0%) (Figure 3).

Factors associated with psychological distress in women with BBD and BC

To identify factors contributing to distress, patients were categorized based on their DT scores, with scores ≥4 indicating psychological distress and scores <4 indicating no distress. All variables were analyzed using t-tests or χ2 tests. In the BBD group, univariate analysis showed significant differences in age, education level, marital status, employment status, parity, and BI-RADS classification. Multivariate regression analysis further identified several significant predictors of psychological distress. Younger patients had a higher likelihood of experiencing distress (OR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.94–0.99, p < 0.05). Higher education was associated with greater distress (OR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.16–3.66, p = 0.01), and employed women had higher distress levels (OR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.01–3.35, p < 0.05). Additionally, women with higher BI-RADS scores experienced greater distress (OR = 2.76, 95% CI: 1.50–5.08, p < 0.01).

Differentiation by age, level of education, and employment status were revealed in the univariate analysis of the BC group. Multivariate regression analysis showed that distress levels were influenced by several factors. Younger women reported more distress (OR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.92–0.99, p < 0.05). Women with higher levels of education were more likely to report distress (OR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.02–7.73, p < 0.05), and employed patients reported significantly higher distress levels (OR = 6.44, 95% CI: 2.29–18.12, p < 0.01). Specific data are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 4, Table 5.

To summarize, psychological distress was prevalent in both groups but more common in BC patients (63.6%) as compared to those with BBD (52.2%). For both groups, anxiety and fear were the most marked sources, but in BC patients, financial concerns along with depression were more pronounced. Younger age, higher education, and employment status were significant predictors of distress in both groups. However, BI-RADS classification was another determinant for BBD patients. These conclusions call for further thought on the importance of proactive psychological screening and targeted interventions for women being diagnosed with breast diseases to optimize their mental health.

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the 1st research attempting to measure the distress levels of women with BC and BBD before the diagnosis is made. Two key findings emerged from this cross-sectional study. First, distress prevalence was higher in the BC group (63.6%) compared to the BBD group (52.2%). Second, age, education, and employment status were predictors of distress in both groups, while a higher BI-RADS grade was associated with increased distress levels in the BBD group.

Previous studies have primarily examined psychological distress in BC patients after diagnosis or during treatment. In Malaysia, 1 study reported a distress prevalence of 50.2% at diagnosis,17 while a study conducted in the USA found a rate of 53.3% with Asian individuals having the highest percentage at 60.7% compared to other ethnic groups.18 A study conducted in China among 137 patients undergoing chemotherapy reported a distress rate of 42.3%.19 Our study suggests that BC patients often experience heightened psychological distress before receiving a diagnosis, with levels surpassing those observed during the treatment phase. This elevated pre-diagnosis distress may stem from cultural factors. Additionally, BC diagnosis often involves life-changing physical impacts and typically occurs between ages 45 and 55 – a stage where many women are managing significant family and financial responsibilities. These combined pressures contribute to increased psychological distress among Chinese BC patients before diagnosis.

Cultural perceptions of BC play a crucial role in shaping distress levels. In China, cancer is often perceived as a terminal illness, leading to heightened fear and anxiety even before a definitive diagnosis. Additionally, family expectations and social obligations contribute to distress, particularly for women who bear caregiving responsibilities. The stigma associated with a cancer diagnosis may further exacerbate psychological burdens, as individuals may fear social exclusion or discrimination.

A noteworthy finding from our study is the high level of pre-diagnostic distress reported among women with BBD. Prior research has shown that BBD patients can experience psychosocial challenges similar to those faced by BC patients.20 Our findings are consistent with previous research showing that women attending a breast clinic for the 1st time often experience high levels of anxiety.21 Psychological distress can emerge from the moment a breast lump is discovered and may persist through follow-up appointments for abnormal findings, regardless of whether the ultimate diagnosis is benign or malignant.14, 22, 23 This heightened anxiety is understandable, as subjective symptoms can trigger fears of cancer, which in turn increase psychological distress. Therefore, it is essential for healthcare providers to offer psychological support to all patients awaiting diagnostic results, not just those at high risk of malignancy.24

Both groups of patients reported anxiety and fear during the diagnostic phase, which can be attributed to the uncertainty surrounding a potential cancer diagnosis. This uncertainty often leads to heightened feelings of anxiety and fear.14, 22, 23 However, in the BC group, emotional distress was particularly prevalent before diagnosis, with 21% of patients indicating financial pressures. The costs associated with cancer treatment can be significant in China, contributing to stress and financial strain for patients.25, 26 In contrast, women in the BBD group also identified childcare responsibilities as a factor of psychological distress. Given that BBD patients tend to be younger, concerns related to parenting may weigh more heavily on them. Previous research has shown that having children is a strong predictor of distress, particularly among younger women.27

Our study revealed a notable link between psychological distress and factors such as age, education level, and employment status in both the BBD and BC groups. Specifically, we found a negative correlation between age and psychological distress, indicating that younger individuals are more likely to experience higher levels of distress. This observation aligns with findings from various studies.28, 29 Younger BC patients often bear greater social roles and family responsibilities, which can substantially disrupt their work, academic pursuits, and family life during diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, compared to older patients, younger individuals tend to have heightened concerns about their appearance and fertility, making it challenging for them to accept BC surgeries and subsequent treatments. Lastly, despite improvements in the 5-year survival rates for BC, younger patients often express greater anxiety about potential recurrence. These combined pressures contribute to increased psychological distress in this demographic.30, 31

This study reveals that BC patients with higher educational attainment experience a greater prevalence of significant psychological distress, aligning with previous research conducted in China.32 More educated individuals may have a deeper understanding of their diagnosis and treatment, making them more aware of potential health risks. Consequently, this knowledge can contribute to elevated levels of psychological distress.

Additionally, our findings indicate that individuals who are employed report higher levels of psychological distress compared to those who are unemployed. Employed individuals may experience heightened psychological distress due to concerns about job security and financial stability resulting from their illness, especially in workplaces where health conditions may affect career prospects. The stress associated with work responsibilities can further exacerbate these feelings.33 However, some studies suggest that unemployed individuals may also be particularly vulnerable to psychological distress due to financial insecurity and lack of social support.34, 35 Thus, additional research is warranted to identify the specific stressors affecting patients to better understand this relationship.

Our study highlights a link between higher BI-RADS classifications and increased distress levels. The BI-RADS provides a standardized framework for reporting breast pathology detected through mammography and ultrasound.36 It helps categorize breast lesions based on their possibility of malignancy, with higher grades often leading to further testing or biopsies. Patients categorized as probably benign (BI-RADS 3) or with low suspicion (BI-RADS 4a) are frequently encountered and typically warrant short-interval follow-ups or biopsies.37 This observation aligns with findings from earlier research showing that patients with higher BI-RADS scores report greater anxiety,12, 38 as elevated BI-RADS categories often necessitate further biopsies or surgical interventions, thereby amplifying the psychological burden on patients.

Limitations

While our findings provide valuable insights, this study has several limitations. First, the research was conducted with a relatively small sample of patients from a single center, which may restrict the broader applicability of the results. Future studies should incorporate multi-center data to capture a more diverse patient sample. As a second limitation of the study, it has relied on the experience of only inpatient individuals, which may lead to psychological neglect. Examining outpatient cases in future studies may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological phenomena experienced by different patients. Moreover, the study was conducted in China, where cultural and socioeconomic factors may influence distress levels differently than in Western countries. While we identified key distress predictors, future research should explore additional psychological and social factors, such as coping mechanisms, social support networks, and access to mental health resources. Lastly, as a cross-sectional observational study, it only offers a snapshot of psychological distress at a specific moment. The absence of longitudinal data limits the ability to assess changes in distress over time. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to monitor the progression of psychological distress and examine factors that may either intensify or alleviate these feelings, ultimately informing more effective management strategies.

Despite these limitations, our study highlights the need for early psychological support for both BC and BBD patients. Addressing distress during the diagnostic phase could improve patient wellbeing and enhance treatment outcomes. Future studies should explore targeted interventions, such as counseling and financial support programs, to help reduce psychological burdens in this patient population.

Conclusions

Psychological distress is often overlooked in breast disease patients, especially in China, where routine screenings are not yet standard practice. Additionally, there is a shortage of standardized assessment tools for evaluating psychological distress. This study highlights that psychological distress can arise not only from cancer diagnoses but also from benign tumors. Patients with breast diseases may encounter psychological challenges at various stages of their care. Therefore, it is crucial for medical institutions to prioritize the screening and management of psychological distress while increasing their focus on mental health. It is advisable for healthcare facilities to implement routine screenings for psychological distress at key stages of breast disease management, utilizing tools such as the DT. Early identification of distress can help provide timely psychological support, reduce anxiety, and improve overall wellbeing. Hospitals and clinics should also consider offering targeted interventions, such as counseling services, psychoeducational programs, and peer support groups, to address the specific concerns of different patient groups, especially to subgroups such as younger patients, those with lower educational levels, and individuals facing employment instability. By prioritizing mental health alongside physical treatment, medical institutions can enhance patient care, satisfaction, and quality of life.

This article is based on a previously available preprint posted on Research Square on Nov 29, 2023: “Prevalence and correlates of distress in Chinese women with benign breast disease”. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3639926/v1

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14925760.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16014359. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Shapiro–Wilk Test for Normality of Age in Each Group

Supplementary Table 2. Logistic Regression Assumption Tests

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.