Abstract

Background. Vascular injury is a central and early feature of systemic sclerosis (SSc) pathogenesis. Although nailfold capillaroscopy (NC) effectively visualizes characteristic peripheral arteriolar and capillary changes, the retinal microcirculation provides a noninvasive, high-resolution view into subtler vascular dysfunction. Consequently, retinal vascular imaging may offer an ideal modality for monitoring microvascular injury and detecting early manifestations of SSc.

Objectives. To compare retinal microvascular parameters between SSc patients and healthy controls using adaptive optics (AO) imaging, and to evaluate the correlation between adaptive optics-derived retinal measurements and NC findings in SSc.

Materials and methods. The study included 31 patients with SSc and 41 healthy controls. The AO images of the retinal arteries were obtained in both groups and the measurements were compared. Nailfold capillaroscopy was also performed in the SSc cohort, and its findings were directly compared with the AO imaging results.

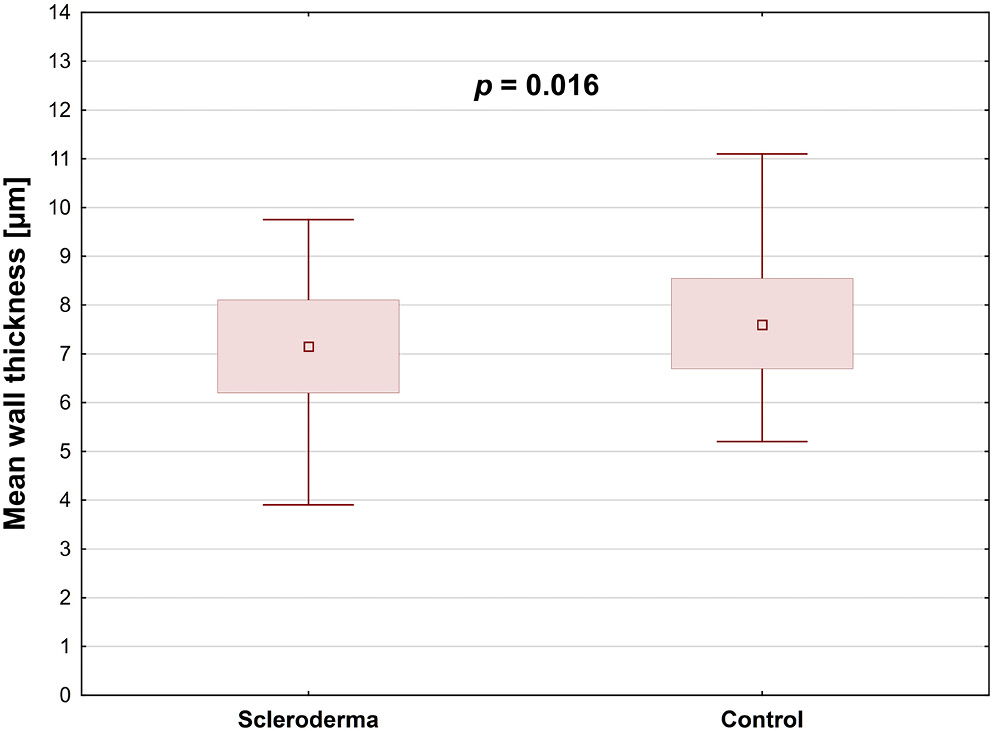

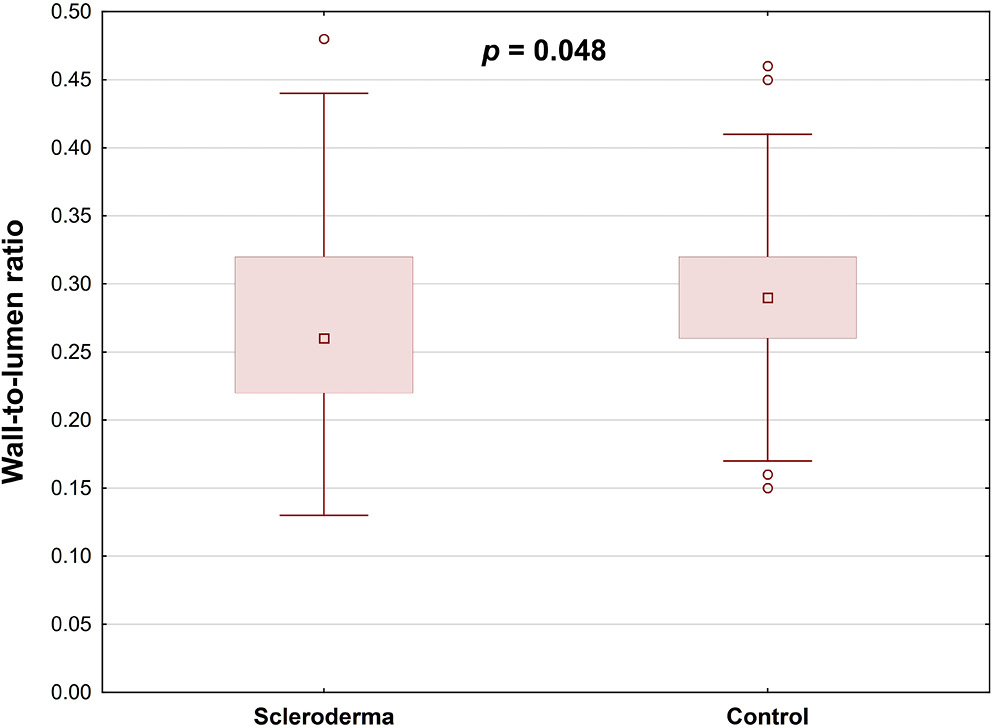

Results. Retinal arterial wall thickness was significantly lower in SSc patients than in healthy controls (p = 0.016), and the wall-to-lumen ratio was similarly reduced in the SSc group (p = 0.048). Within the SSc cohort, hypertensive patients exhibited a significantly greater wall cross-sectional area compared to those without hypertension (p = 0.026).

Conclusions. Adaptive optics retinal imaging demonstrated a significant reduction in mean arterial wall thickness in SSc patients compared with healthy controls. However, no correlation was identified between the AO findings and the NC parameters or the disease stage. Our analysis revealed that alterations in retinal vascular parameters were confined to SSc patients with comorbid hypertension or those receiving sildenafil therapy. To fully establish the clinical utility of adaptive optics imaging in SSc, and to elucidate its relationship with NC findings, larger, multicenter studies with more diverse patient cohorts are warranted.

Key words: systemic sclerosis, scleroderma, adaptive optics, nailfold capillaroscopy, retinal microvasculature

Background

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a connective tissue disorder caused by autoimmunity. It is characterized by obliterative vasculopathy, widespread fibrosis and a dysregulated immune response.1, 2 Vascular involvement represents an initial and pivotal factor in the pathogenesis of the disease, as well as in the development of multiple organ dysfunction. The vasculopathy in SSc includes thrombosis, vasospasm and vessel lumen obliteration leading to microangiopathy.2 Microcirculatory changes observed in the capillaries are the hallmark of the disease.

Nailfold capillaroscopy (NC), as a noninvasive imaging technique, is routinely used to assess peripheral capillary abnormalities in scleroderma patients and is included in the diagnostic criteria for SSc.3, 4 Therefore, this tool plays a pivotal role in both diagnosing and monitoring the progression of the disease.

A range of ocular manifestations have been observed in patients with scleroderma, including those affecting the posterior segment of the eye.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Recent research has concentrated on retinal and choroidal alterations observed in these individuals. Advanced imaging methods, such as optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA), have facilitated the detection of structural changes in the retinal microvasculature linked to systemic diseases.

Adaptive optics (AO) imaging represents a noninvasive tool for the visualization of retinal structures, including photoreceptors, blood vessels and nerve fibers, in vivo at the microscopic level. The camera employs infrared illumination with a wavelength of 850 nm.11 The AO technology is employed for the evaluation of retinal vessels in healthy eyes and arterial hypertension, as well as in ocular pathologies such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, retinal vessel occlusion and retinal vasculitis.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

Objectives

The study aimed to assess and compare the retinal microvasculature parameters in scleroderma patients and healthy controls using AO imaging. Furthermore, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between NC findings, disease characteristics and AO results within the SSc group.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted at the Military Institute of Aviation Medicine (Warsaw, Poland) between March 2022 and May 2023. The study received approval from the Ethics Committee Reviewing Biometric Research at the Military Institute of Aviation Medicine (approval No. 1/2022) and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The purpose and procedures of the study were thoroughly explained to the participants, and written consent was subsequently obtained from individuals. The study sample comprised patients with SSc from the Department and Polyclinic of Systemic Connective Tissue Diseases at the National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation in Warsaw. Healthy participants were enrolled during routine appointments at the Department of Ophthalmology in the Military Institute of Aviation Medicine.

Participants

A total of 31 patients (61 eyes) diagnosed with SSc and 41 healthy controls (81 eyes) were included in this and our previous study.23 No significant differences were observed between the scleroderma patients and the control group regarding age, gender distribution or axial length (Table 1, Table 2). Within the study cohort, 71.4% of patients were diagnosed with diffuse cutaneous SSc, while 28.6% were diagnosed with limited cutaneous SSc. Nailfold capillaroscopy revealed an early scleroderma pattern in 5 patients, an active pattern in 12 and a late pattern in 9. Within the SSc cohort, 2 patients had pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), 8 developed digital ulcers and 8 were hypertensive. A total of 13 participants were treated with sildenafil, while 12 were treated with amlodipine. Interstitial lung disease was identified in 11 patients, of whom 64% were classified as having nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and 36% as having usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). Elevated pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (proBNP) levels were observed in 16.1% of the studied cases (Table 3).

Methods

A comprehensive ophthalmic examination was performed on all participants. This included assessments of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure, refraction, anterior segment examination, fundoscopy with pupillary dilatation, and axial length (AL) measurement. Exclusion criteria were refractive errors beyond −3.0 or +3.0 diopters and any pathological ocular condition, including glaucoma or retinal and choroidal diseases. Moreover, eyes with low-quality AO images were also excluded. The BCVA was measured monocularly using LogMAR charts (Lighthouse International, New York, USA) at 5 m, while AL was assessed using the IOL Master 500 (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany).

All participants with scleroderma underwent a clinical evaluation and NC. The clinical data collected from each SSc patient comprised the following: The type of SSc (either limited or diffuse cutaneous scleroderma), the presence of interstitial lung disease (classified as either NSIP or UIP), hypertension, elevated proBNP, and the treatment method (administrations of sildenafil or amlodipine). The NC was conducted using the CapillaryScope 200 Pro (Dino-Lite, Taipei, Taiwan), following the manufacturer’s guidelines. To ensure consistency, all images were captured by the same expert, maintaining uniformity in lighting, focus and positioning.

The study aimed to categorize scleroderma microangiopathy using the Cutolo classification and to assess multiple capillaroscopic parameters – vessel density, hemorrhages, capillary morphology, giant capillaries, and avascular areas. The classification was based on identifying specific capillary abnormalities linked to different disease stages. In each NC image, vessel density was classified as normal (≥7 capillaries), reduced (4–6 capillaries) or severely reduced (≤3 capillaries). This classification offered valuable insights into the microvascular changes linked to the progression of scleroderma. For each participant, we recorded capillaroscopic features – including hemorrhages, tortuous (branched) vessels, giant capillaries, and avascular zones – offering crucial insight into the microvascular abnormalities characteristic of SSc.24 The Dino-Lite capillaroscope underwent routine quality control checks, during which calibration images were acquired to confirm accurate color reproduction and resolution.

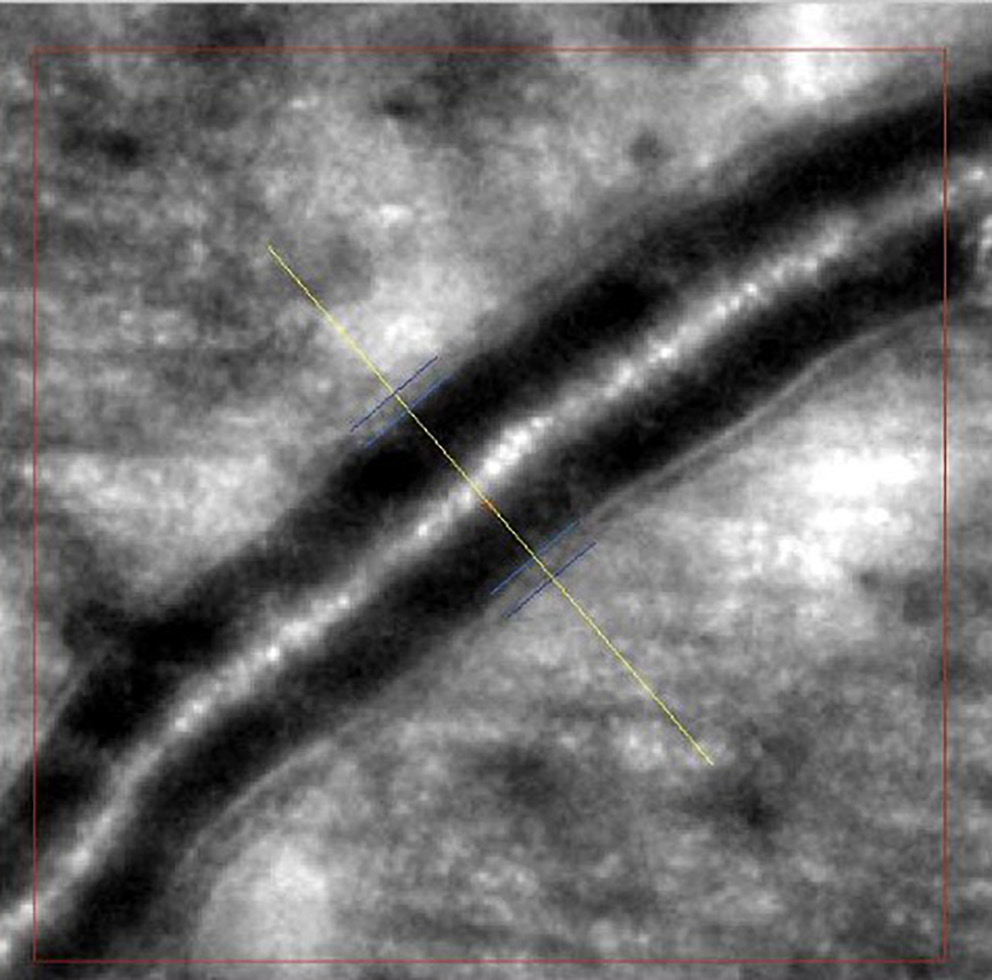

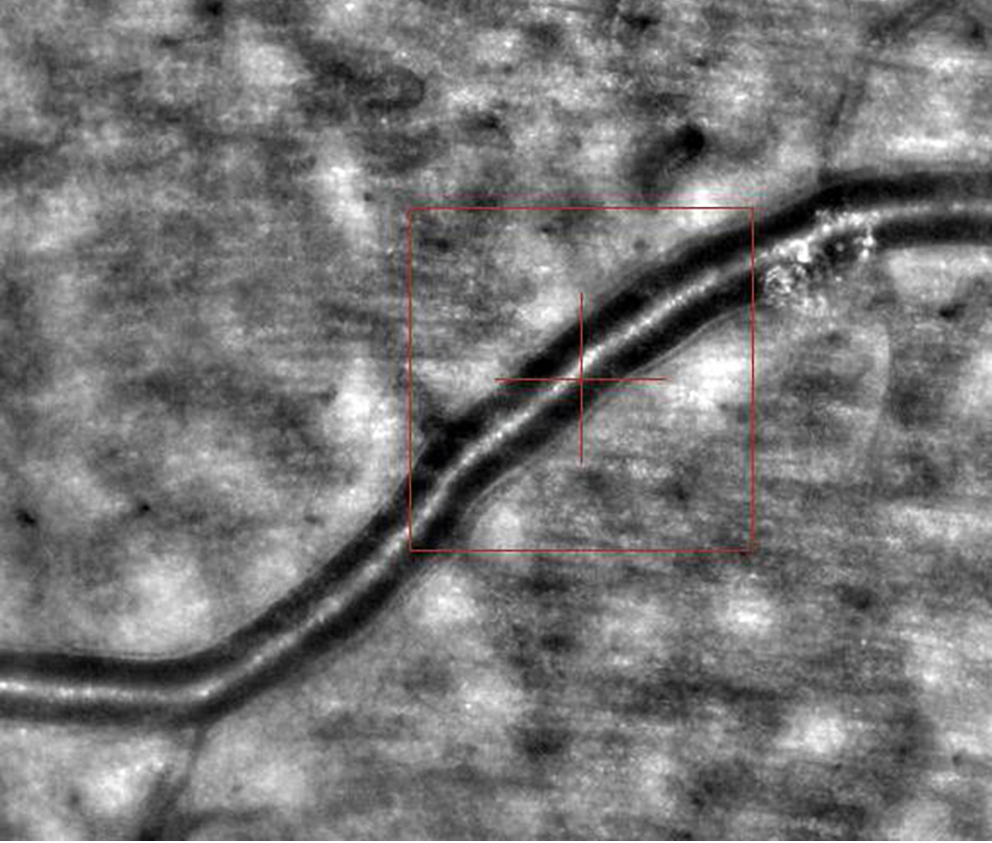

Images of retinal arterioles using an AO retinal camera (rtx1™; Imagine Eyes, Orsay, France) were captured in both patient groups. Before imaging, participants received 1 drop of 1% tropicamide for pupil dilation. Retinal artery images were analyzed with AOdetectArtery software (rtx1™; Imagine Eyes), focusing on the superior quadrant arterioles with a lumen diameter of at least 40 μm and no bifurcations. Two measurements were taken, and the highest-quality scan was selected for analysis.

The main vascular parameters obtained with AO were total vessel diameter (TD), lumen diameter (LD) and wall thickness (WT). The software also calculates 2 additional vascular metrics: The wall-to-lumen ratio (WLR), defined as wall thickness (WT) divided by lumen diameter (LD), and the wall cross-sectional area (WCSA), computed as π × [(TD/2)2 – (LD/2)2], which represents the area occupied by the vessel wall (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Statistical analyses

Qualitative variables were shown as integers with percentages. Quantitative parameters were presented according to their weighted arithmetic mean, median, standard deviation (SD), and min–max values. Relationships among the examined qualitative variables were illustrated using contingency tables. Relationships among categorical variables were assessed using Pearson’s χ2 test when all expected cell counts were ≥5, and Fisher’s two-tailed exact test when any expected count fell below 5. The Shapiro–Wilk W test was used to assess the normality of distribution and Levene’s test was fitted to check the homogeneity of variances. Differences between independent groups for normally distributed numerical variables with homogeneous variances were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) without replication. Variables failing to meet normality or homogeneity of variance assumptions were analyzed with nonparametric tests – namely, the Mann–Whitney U test for dichotomous independent variables and the Kruskal–Wallis H test for variables with more than 2 categories. A level of p < 0.050 was deemed statistically significant. All the statistical procedures were performed using STATISTICA v. 13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, USA).

Results

The study included 31 SSc patients (61 eyes) and 41 healthy controls (81 eyes). No significant differences between the 2 groups regarding retinal arteries TD, LD, second wall thickness, and WCSA were found (Table 4). Mean retinal arterial wall thickness was significantly lower in SSc patients than in healthy controls (p = 0.016), and the wall-to-lumen ratio was also notably decreased in the SSc group (p = 0.048) (Table 4; Figure 3, Figure 4).

Retinal vessel parameters obtained through AO, including TD, LD, wall thicknesses, WLR, and WCSA, were analyzed in relation to NC findings and clinical features of SSc. No statistically significant correlation was observed between retinal vessel parameters and capillaroscopic patterns, nor between these parameters and the type of SSc (Table 5, Table 6, Table 7). The WCSA was significantly higher in hypertensive SSc patients compared to those without hypertension (p = 0.026; Table 7).

Discussion

Vascular damage is a hallmark of SSc and plays a pivotal role in its pathogenesis. It has been established that microvascular changes primarily affect peripheral arterioles and capillaries. Generalized vasculopathy has been demonstrated to contribute significantly to perfusion disorders in both the retina and the choroid. Therefore, the retinal microvasculature offers an ideal window for monitoring disease progression and detecting early pathological changes. Previous studies have shown that retinal findings, such as hard exudates, vascular tortuosity and arterial narrowing, as well as microhemorrhages, have been discovered in patients with SSc during fundus examination.25, 26, 27 The presence of small retinal capillary abnormalities can be detected through a range of diagnostic techniques, including OCTA and fluorescein angiography (FA). The morphological changes in the retinal caliber, shape, or lumen diameter are valuable for assessing the state of microcirculatory perfusion. Therefore, we hypothesized that adaptive optics retinal imaging, as a novel noninvasive method, could aid in the detection of abnormalities in the structure of retinal vessels.

In this study, AO was used for retinal artery assessment in both groups. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to use AO imaging in SSc. A comparison of the 2 groups revealed no statistically significant differences in terms of LD, TD and WLR. According to previous studies, WLR and WCSA are optimal parameters for evaluating vascular remodeling in cases of diabetic retinopathy and arterial hypertension.11, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Żmijewska et al. analyzed arterial measurements using AO in 36 patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (DR). Their results demonstrated thicker arterial walls, increased WLR and WCSA in DR group than in controls.29 Matuszewski et al.33 and Cristescu et al.34 also demonstrated comparable outcomes. However, our results showed that the WLR was significantly decreased among SSc patients compared to the healthy group (p = 0.048).

Lombardo et al.35 reported that, in eyes with nonproliferative DR, the parafoveal capillary lumen diameter was significantly reduced compared to healthy controls. Similarly, Zaleska-Żmijewska et al.18 demonstrated that prediabetic patients exhibit distinct alterations in both capillary lumen diameter and wall-to-lumen ratio relative to control subjects.

An elevated WLR reflects both thickening of the vessel wall and concomitant narrowing of the lumen. Piantoni et al.36 used AO in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis treated with abatacept to evaluate cardiovascular risk factors. Their results indicated a significant reduction in the WLR of the arterioles after abatacept treatment. However, our results showed that the mean arterial wall was thinner in the scleroderma group than in the controls (p = 0.016). It is possible that the observed results may be attributed to the vasodilator treatment employed in the management of SSc.37

Pache et al.37 demonstrated that in 10 healthy volunteers, a single dose of sildenafil induced significant dilation of both retinal arterioles and venules 30 minutes after administration (p < 0.001). Moreover, Polak at al.38 reported increased retinal blood flow in healthy controls after sildenafil administration. Sildenafil can enhance the vasodilatory effect of nitric oxide (NO), the primary regulator of vascular smooth muscle tone. In addition, we compared the measurements of the retinal arteries obtained in AO with the results of the NC. However, we did not find a statistically significant correlation with the type of scleroderma, finger ulcers and scleroderma patterns, number of vessels, avascular areas, hemorrhages, or branched vessels visualized in NC. In our previous study, we found that scleroderma microangiopathy patterns correlated significantly with both superficial and deep foveal avascular zone (FAZ) areas, as well as with deep retinal vessel density measured by OCTA.23 Several studies have explored the relationship between peripheral capillary density measured with nailfold capillaroscopy and both choriocapillaris vessel density39 and overall retinal perfusion.40 However, these findings have been inconsistent. It is therefore possible that high-resolution imaging of the retinal microvasculature may yield stronger correlations with NC abnormalities.

These findings corroborate earlier reports that hypertension is associated with increased wall cross-sectional area, reflecting arteriolar remodeling.11 Furthermore, in our study, we evaluated the impact of vasodilator medications employed for the management of complications associated with scleroderma vasculopathy. Contrary to expectations, the findings of this study indicated a decreased LD in patients treated with sildenafil (p = 0.017). It is worth noting that most patients in our NC cohort exhibited a late scleroderma pattern – reflecting severe vasculopathy and advanced disease – so the observed arterial lumen narrowing likely reflects the chronicity and severity of SSc.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the research, including the relatively small number of participants and the cross-sectional nature of the study.

Conclusions

Our study analysis of the AO retinal imaging data set revealed a reduced mean arterial wall thickness in patients with SSc compared to healthy controls. However, no correlation was identified between the AO findings and the NC parameters or the disease stage. The retinal vessel parameters revealed significant differences only in hypertensive or sildenafil-treated patients. Further studies on a larger cohort of patients are necessary to draw reliable conclusions about the usefulness of AO in the diagnosis of SSc and its possible correlation with capillaroscopic findings.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.