Abstract

Background. Multidrug resistance remains a major obstacle in the treatment of ovarian cancer (OC) patients. Recent research has underscored the critical role of extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA) in tumor initiation and progression. However, there is limited comprehensive understanding of the role eccDNA plays in tumor resistance.

Objectives. This study investigates the involvement of WWP1-eccDNA in the resistance mechanisms of OC.

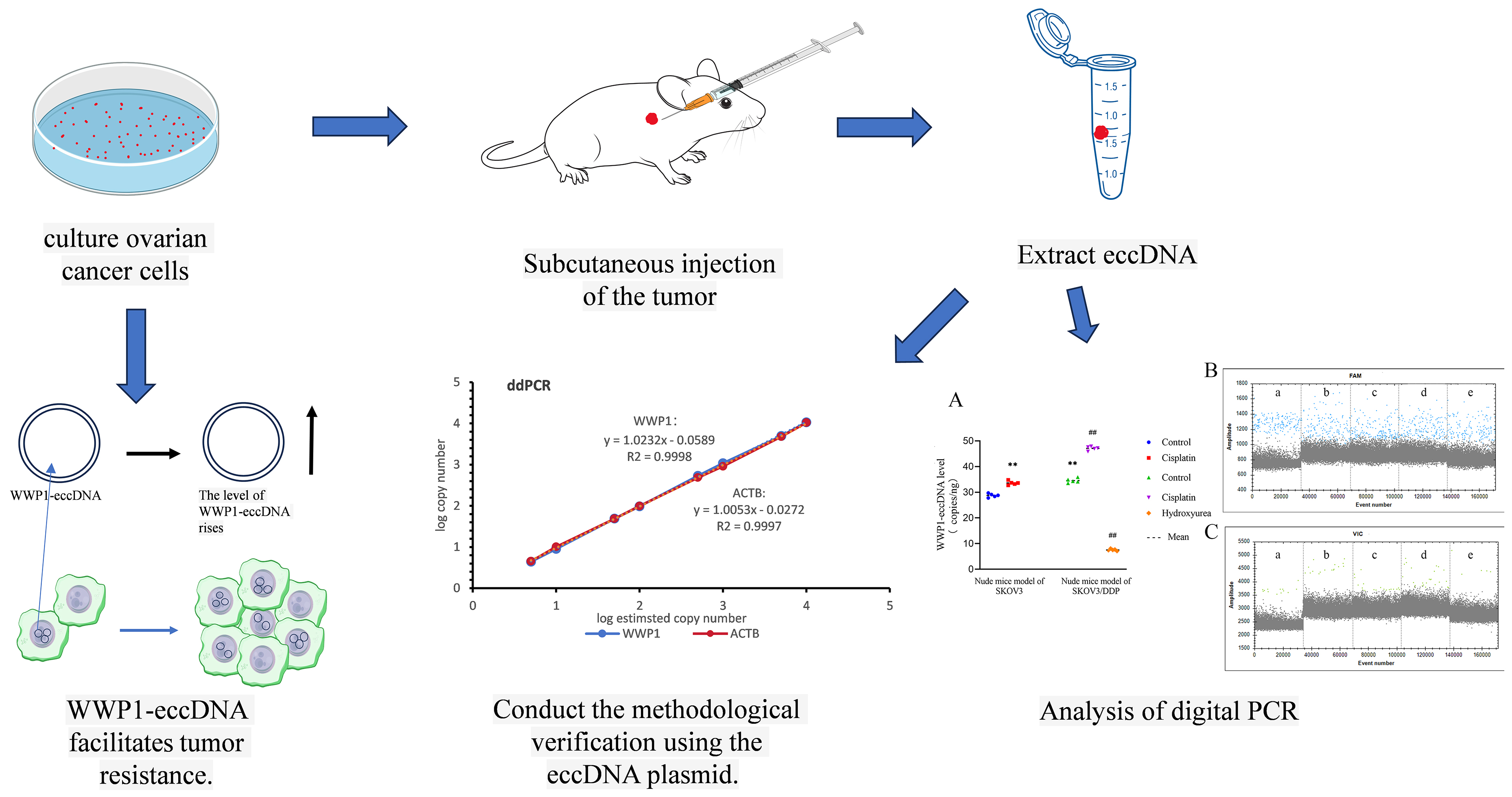

Materials and methods. Human OC cells (SKOV3 and cisplatin-resistant SKOV3/DDP) were cultured and high-throughput sequencing was performed, leading to the identification of eccDNA in SKOV3/DDP cells. Female BALB/cA-nu nude mice with SKOV3 and SKOV3/DDP xenografts received cisplatin (5.5 mg/kg), hydroxyurea (50 mg/kg) or saline for 14 days, followed by tumor weight assessment. Digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) were used to quantify WWP1-eccDNA, evaluating their sensitivity and accuracy. Linear DNA removal and BsmI digestion were tested to improve eccDNA detection.

Results. WWP1-eccDNA was among the top upregulated eccDNA in SKOV3/DDP cells. Both cisplatin and hydroxyurea reduced tumor growth in mice, with cisplatin showing limited efficacy in resistant tumors. The ddPCR outperformed RT-qPCR in sensitivity, and linear DNA removal improved WWP1-eccDNA detection. WWP1-eccDNA levels were significantly elevated in SKOV3/DDP tumors. Treatment with cisplatin further increased its expression, whereas hydroxyurea led to a reduction in WWP1-eccDNA levels.

Conclusions. WWP1-eccDNA is critical in OC resistance, with cisplatin treatment increasing WWP1-eccDNA levels, contributing to resistance. The ddPCR proves to be a superior method for eccDNA detection.

Key words: ovarian cancer, chemoresistance, WWP1, extrachromosomal circular DNA, droplet digital PCR

Background

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the most lethal gynecological malignancy, with the highest mortality rate among related diseases. Around 70% of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages after substantial disease progression.1 Consequently, the 5-year survival rate for these patients is alarmingly low, at around 30%.2 Currently, chemotherapy represents the primary therapeutic strategy for OC; however, its effectiveness is significantly compromised by both inherent and acquired resistance of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents, as well as their strong tendency to metastasize. Multidrug resistance (MDR) plays a central role in reducing chemotherapy efficacy, leading to treatment failure and cancer recurrence. Notably, more than 90% of OC deaths are linked to drug resistance.3

WWP1, a HECT-type (homologous to the E6-AP carboxyl terminus) E3 ubiquitin ligase, regulates the ubiquitination of multiple substrates. It is frequently overexpressed or aberrantly activated in various cancers and is associated with poor clinical prognosis.4 Recent preclinical studies have identified WWP1 as a promising therapeutic target in cancer and other diseases. The overexpression of WWP1 is particularly detrimental because it promotes the polyubiquitination of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN, leading to its functional inactivation. This gene, often mutated, deleted, downregulated, or silenced in cancers, is critical for regulating cell growth. The alteration of PTEN by WWP1 impedes its dimerization and membrane localization, compromising its tumor suppressor function. Consequently, this deregulation activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, enhancing tumor cell survival and contributing to MDR. Intriguingly, inhibiting WWP1 has been shown to restore PTEN’s tumor suppressor function, regardless of the gene’s mutational status, thereby inhibiting tumor growth and potentially reversing MDR.5 WWP1 is frequently overexpressed or mutated in multiple malignancies, such as colorectal, liver and breast cancers.6, 7, 8 Although WWP1’s role in other malignancies is well documented, its contribution to OC and treatment resistance remains unknown. Our study addresses this gap by exploring its eccDNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms.

Extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA) is a form of circular DNA that exists independently of chromosomes and is associated with oncogene amplification, as well as its strong tendency to promote tumor metastasis. Eccentric circular DNA (eccDNA) molecules were first identified in 1965 through optical microscopy in malignant tumor cells of children. These structures were frequently observed in pairs and became known as double minutes (DMs). The significance of eccDNA in cancer development has gained recognition in recent years thanks to advances in next-generation sequencing and ultra-high-resolution imaging technologies. These studies have established a clear link between oncogene amplification in eccDNA and adverse outcomes in cancer patients.9 The eccDNA contributes to tumor pathology by amplifying oncogenes, supporting the synthesis of proteins that promote tumor growth, mutations and cellular invasion. This oncogenic overexpression is a crucial factor in the aggressive behavior of tumors.10 For instance, a recent study showed that eccDNA-induced RAB3B promotes autophagy, thereby increasing resistance to cisplatin in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. These findings suggest that targeting eccDNA may represent a promising strategy to overcome tumor drug resistance.11 However, current methods for detecting eccDNA are still limited.

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) has emerged as a transformative technology in scientific research, particularly for precise quantification of nucleic acids. Unlike real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), ddPCR enhances accuracy by partitioning the sample into tens of thousands of separate reaction compartments, each containing a tiny volume of the reaction mixture. This partitioning ensures that each compartment likely contains 0 or 1 nucleic acid template molecule. After amplification, fluorescent signals from each compartment are measured. These data are then used to calculate the concentration or copy number of the target molecule using the Poisson distribution.12 This method provides absolute quantification of nucleic acids in a sample, making it a powerful tool in medical research, especially in oncology, where it is used to analyze genetic variations in cancers such as breast and gastric cancers.13, 14, 15

Objectives

In this study, we performed sequencing of extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA) from the OC cell lines SKOV3/DDP and SKOV3, which led to the identification of eccDNA encoding WWP1. To validate these findings, we employed the advanced droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) technique.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human OC cell line SKOV3 and its cisplatin-resistant variant SKOV3/DDP were acquired from Zhejiang Meisen Cell Technology Co. (Zhejiang, China; cat. No. CTCC-001-0011). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution, both purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, USA). Cultures were maintained in a BINDER cell thermostatic incubator (BINDER GmbH Co, Tuttlingen, Germany) set at 37°C with an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The culture medium was replaced every other day, and cells were passaged every 3–4 days to maintain optimal growth conditions. To preserve the cisplatin resistance phenotype, a concentration of 0.2 μg/mL cisplatin was continuously present in the culture medium of the SKOV3/DDP cells.

High-throughput sequencing of eccDNA

The SKOV3 and SKOV3/DDP cells were resuspended in L1 buffer from the Plasmid Mini AX kit (A&A Biotechnology Inc., Gdańsk, Poland), which included protease K from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and were digested overnight at 50°C. Following digestion, the samples underwent alkaline treatment and were purified using a column according to the instructions provided with the Plasmid Mini AX kit. The column-purified DNA was treated with FastDigest MssI enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C for 16 h to eliminate mitochondrial circular DNA. Subsequently, Plasmid-Safe ATP-dependent DNase (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, USA) was added. Thirty units of the enzyme and the appropriate amount of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) were supplemented every 24 h for a total incubation of 1 week to ensure complete removal of residual linear DNA. These enzymatically treated samples served as templates for amplifying eccDNA using the RCA DNA Amplification Kit (GenSeq Inc., Shanghai, China). The amplified eccDNA was purified with the MinElute Reaction Cleanup Kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). This purified DNA was utilized to construct a library using the GenSeq® Rapid DNA Lib Prep Kit (GenSeq Inc.), which was subsequently sequenced using the NovaSeq 6000 system (IlluminaInc., San Diego, USA) in a 150bp paired-end format. The sequencing data was filtered using SOAPnuke v. 2.1.9 (BGI Research,Beijing, China) to obtain clean reads. HISAT2 v. 2.2.1 (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA) was then employed to align these clean reads to the reference genome. Circle-map v. 1.1.4 (University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to identify eccDNA across all samples. Samtools v. 1.21 (Wellcome Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK) calculated the number of soft-clip reads overlapping with breakpoints to generate raw count numbers. Finally, differential eccDNA expression analysis was performed using edgeR v. 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with a biological coefficient of variation (BCV) parameter set to less than or equal to 0.4 for human data based on the methodological specifications outlined in the official edgeR documentation.16 The pipeline included data normalization, calculation of intergroup fold changes and statistical significance assessment through p-value determination, enabling systematic identification of differentially expressed eccDNAs. The presence and characteristics of identified eccDNA signals were validated using the Integrated Genome Browser (IGB) v. 10.10 (University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, USA), a specialized software platform for genomic data visualization and analysis.

Establishment of a nude mice ovarian cancer model

A total of 25 female BALB/cA-nu mice, aged 4–5 weeks, were obtained from Henan SCBS Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Anyang, China; license No. SCXK2020-0005). Ethical approval for the study (No. NYDLS-2023-004) was granted by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Nanyang Institute of Technology (China) on 13 April 2023. SKOV3 and SKOV3/DDP cells were harvested during the logarithmic growth phase. The cells were enzymatically dissociated using trypsin and gently pipetted to obtain a single-cell suspension. Following centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 6 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the cells were washed 3 times with PBS. The final cell concentration was adjusted to 5 × 106 cells/mL using 0.9% sodium chloride solution. A total of 300 μL of the prepared cell suspension was subcutaneously injected into the flank of each mouse after alcohol disinfection of the injection site. The mice were housed under controlled environmental conditions, including a temperature of 25°C, relative humidity of 50 ±10% and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Tumor formation was typically detectable by palpation at the injection site within 6–7 days post-injection. The health status and general condition of the mice were closely monitored daily throughout the experiment.

Grouping and administration of nude mice

Therapeutic treatment began 7–10 days after the inoculation of subcutaneous tumor cells. Mice inoculated with SKOV3 cells were randomly assigned to either the control group or the cisplatin group. Mice inoculated with SKOV3/DDP cells were divided into 3 groups: the control group, the cisplatin group and the hydroxyurea group, with 5 mice in each group.

Control group: Mice were treated with 0.9% sodium chloride solution, 0.1 mL per 10 g of body weight, administered daily for 14 days.

Cisplatin group: Mice received cisplatin (5.5 mg/kg, CSNpharm Inc., Chicago, USA) in a volume of 0.1 mL per 10 g of body weight, administered every other day for 14 days.

Hydroxyurea group: Mice received hydroxyurea (50 mg/kg, CSNpharm Inc.) in a volume of 0.1 mL per 10 g of body weight, administered every other day for 14 days.

Tumor dissection

Mice were euthanized the day after the final drug administration. Tumors were dissected under sterile conditions, and their weights were recorded. The tumors were subsequently stored at −80°C for future analysis.

Extraction of genomic DNA

Tumors stored at –80°C were retrieved and thoroughly washed with PBS. The tumor tissues were then homogenized using a high-speed, low-temperature tissue grinder to ensure uniform disruption. Genomic DNA was subsequently extracted from the homogenized samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the MagAttract High Molecular Weight DNA Kit (Qiagen Inc.). Proteinase K and RNase A were added to the tissue sample. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. DNA purification magnetic beads were then added. The solution was thoroughly mixed using a mixer. Then, the supernatant was carefully transferred to a new container. The supernatant was washed. Finally, the DNA was eluted using the appropriate elution buffer. The extracted DNA was stored at −20°C for subsequent analysis.

Synthesis of primers and probes

All primers and probes used in this study were synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), including those for ACTB:

(forward: TGCACCTCCCACCG;

reverse: ACAGAGCTTCCCTCCAAGAC;

probe: ACCGTGTTCAGGGTCCCTGTCC-FAM)

and WWP1:

(forward: ACCCTGACCTAGTCAC;

reverse: GAGATTTTAAAAGGATTTATGAAAAATAGG;

probe: TCATGCCTGGTGACCAGGTCACT-VIC).

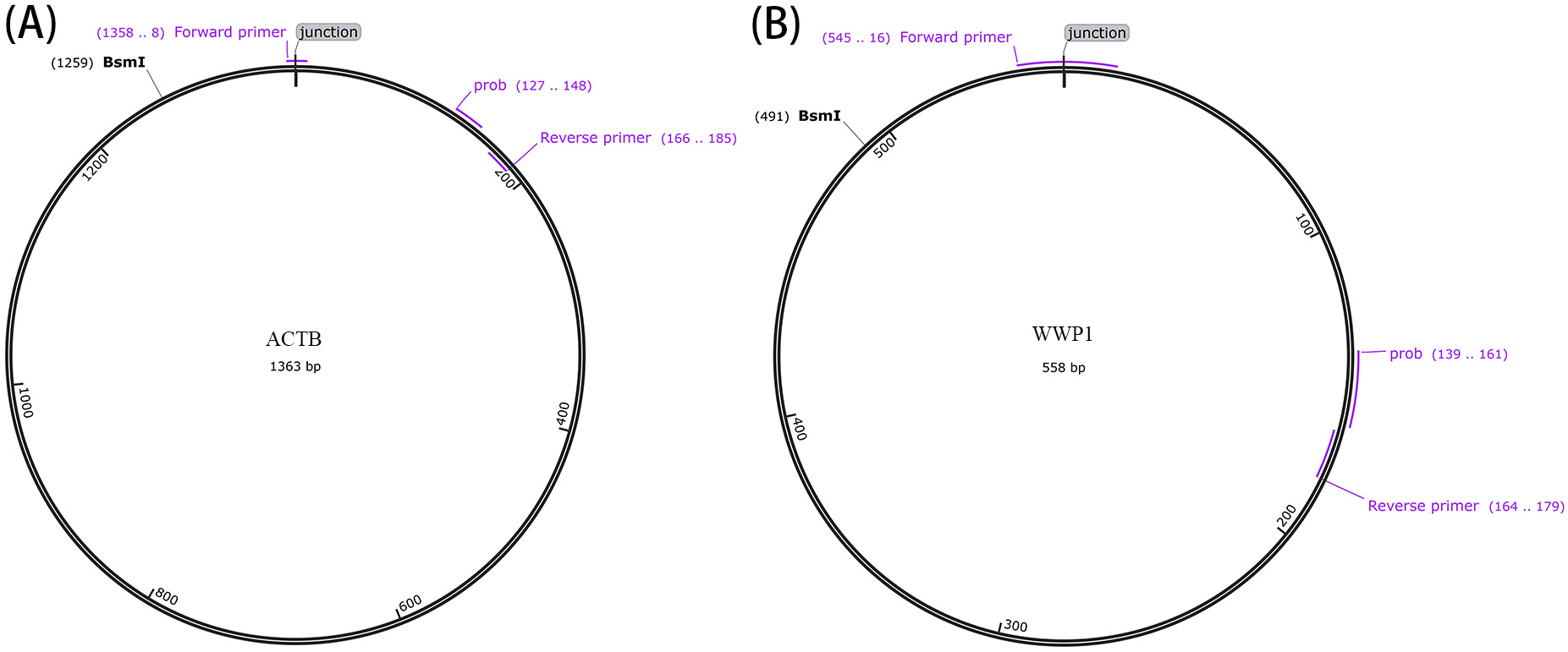

Linear experiment

ACTB and WWP1 plasmids, each at a concentration of 0.01 ng/μL, containing sequences cloned into the PUC57 vector based on identified eccDNA coordinates (ACTB: chr7:5532553-5533915; WWP1: chr8:86395371-86395928, data from High-Throughput eccDNA sequencing, as shown in Figure 1). These plasmids were digested with Bsml endonuclease (New England Biolabs, NEB Inc., Ipswich, USA). The digested plasmids were subsequently diluted 20-fold with deionized water. The plasmids were partitioned into 8 serial dilutions, ranging from 10,000 to 5 copies per μL. These dilutions were analyzed using both RT-qPCR and ddPCR to assess the sensitivity. The digital PCR system (TargetingOne Inc. TD-1; Beijing Xinyi Biological Technology Co., Beijing, China) used a reaction mixture consisting of 7.5 μL of 4 × SuperMix (TargetingOne Corporation, Ltd.), 1.2 μL each of forward and reverse primers (400 nM), 200 nM probe and 50 ng DNA template in a total volume of 30 μL. Cycling conditions were: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 58°C for 30 s; and a final hold at 12°C for 5 min. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed using the CFX Opus96 system (Bio-Rad Inc., Hercules, USA) under similar conditions.

Repeatability experiment

Plasmids containing ACTB and WWP1 sequences were used as templates for ddPCR and RT-qPCR amplification at concentrations of approx. 10,000, 5,000, 1,000, 500, and 100 copies/µL.

Each concentration was tested in triplicate across 3 independent inter-batch experiments, and the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated to assess the repeatability of the method. The reaction systems, primer and probe concentrations, and amplification conditions were consistent with those used in the linearity experiment.

Comparison before and after removal of linear DNA from circular DNA

Genomic DNA extracted from the tumor tissues of the cisplatin-treated SKOV3 nude mice model was divided into 3 aliquots. The 1st sample contained unmodified genomic DNA. In the 2nd sample, linear DNA was removed using the MinElute Reaction Cleanup Kit (Qiagen Inc.). The genomic DNA was added to the buffer solution, and then the resultant liquid was transferred to an adsorption column. Following centrifugation, a washing buffer was introduced. After allowing the system to stand for a defined period, a 2nd centrifugation step was carried out. Finally, an elution buffer was employed to elute the purified product. The 3rd sample, after linear DNA removal, was further treated with Bsml endonuclease. The DNA was incubated at 65°C for 10 min, followed by 80°C for 20 min in a thermal cycler. The presence of WWP1-eccDNA and ACTB-eccDNA in all 3 samples was evaluated using ddPCR. All samples were loaded with a final DNA concentration of 200 ng. The reaction system, primer and probe concentrations, and amplification conditions remained identical to those used in previous experiments.

Comparison of eccDNA in different treatment groups

The extracted genomic DNA from each group was retrieved from storage at –20°C, and linear DNA was subsequently removed. The DNA was then digested with Bsml endonuclease, and ddPCR analysis was performed. The final DNA loading concentration for each sample was 200 ng. The reaction system and amplification conditions remained consistent with those described previously.

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v. 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). Given the small sample size (n ≤ 10), normality testing was intentionally omitted due to insufficient statistical power, and nonparametric methods were uniformly applied. For comparisons between 2 groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied. Multi-group comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. Results were expressed as median (min–max). Statistical significance was set at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

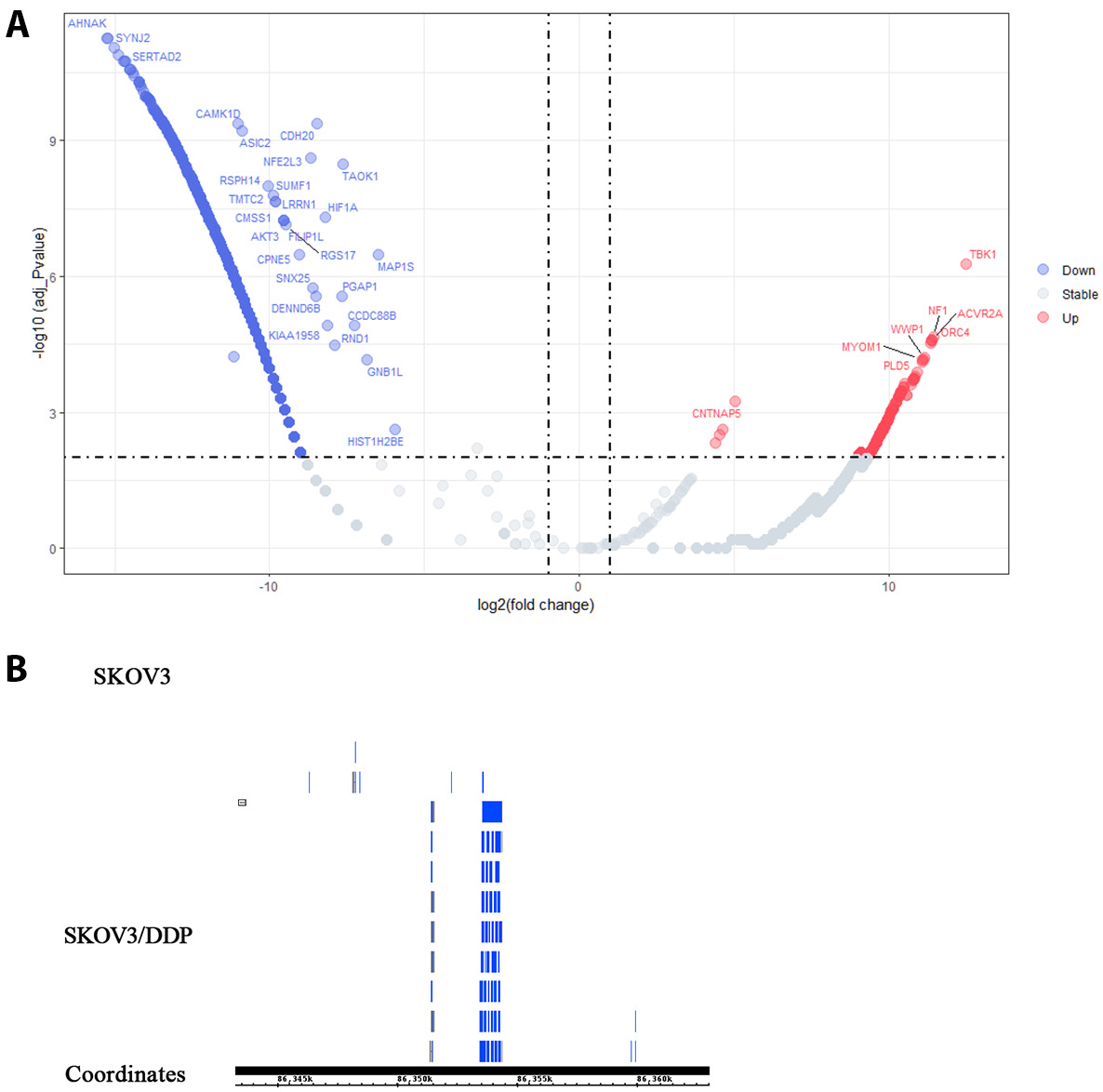

eccDNA differences between SKOV3/DDP and SKOV3 cells

Volcano plot analysis of eccDNA profiling for high-throughput sequencing (Figure 2A) revealed 1,563 differentially expressed eccDNAs meeting predefined thresholds (|log2(fold change)| >1 and FDR-adjusted p < 0.01) between SKOV3 and SKOV3/DDP cells. Of these, 578 eccDNAs (37%) exhibited upregulation (depicted in red), while 986 eccDNAs (63%) showed downregulation (highlighted in blue). Notably, WWP1-eccDNA ranked among the top 10 most significantly upregulated species (log2(fold change) = 11.1, p = 6.36 × 10^−5). The IGB browser analysis of sequencing data confirmed elevated WWP1-eccDNA copy numbers in SKOV3/DDP cells compared to parental SKOV3 cells (Figure 2B). Given the potential role of WWP1 in tumor resistance,5 we further investigated the presence and significance of WWP1-eccDNA in the tumor tissues of nude mice models. This was done following linear and reproducibility experiments designed to detect WWP1-eccDNA in plasmid samples.

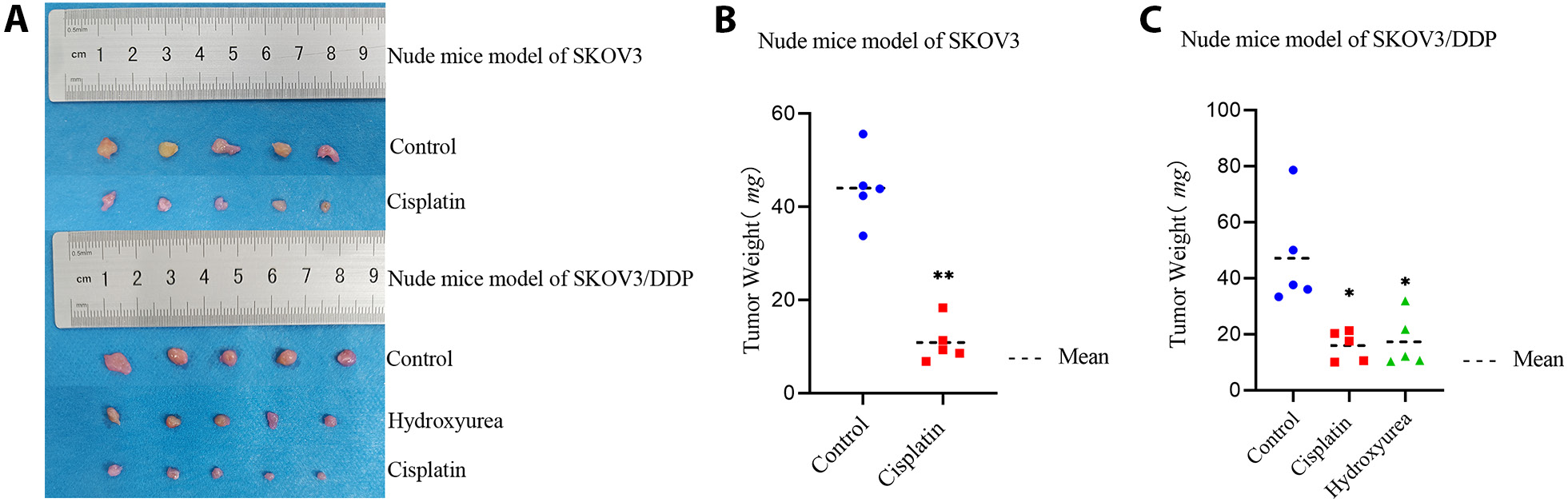

The effects of different treatments on tumor weight

In nude mice models of SKOV3 and SKOV3/DDP, both the cisplatin and the hydroxyurea treatment showed inhibitory effects on tumor growth compared to the control group. The tumor inhibition effect of cisplatin was less pronounced in the SKOV3/DDP model than in the SKOV3 model (Figure 3, Table 1, Table 2), indicating that the SKOV3/DDP mice exhibited resistance to cisplatin (p < 0.05).

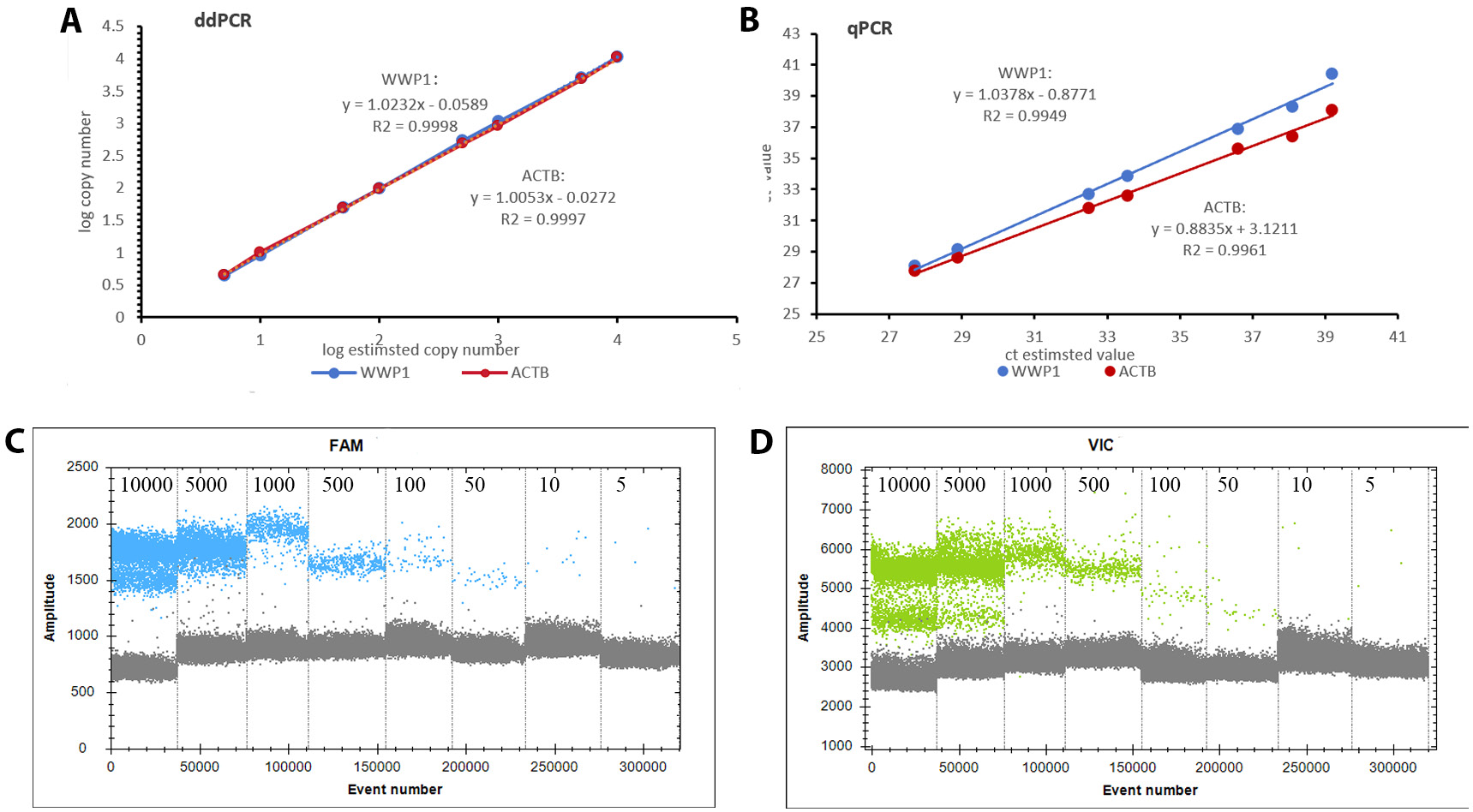

Increased sensitivity for plasmids detection using ddPCR

Analysis of the standard curve generated using RT-qPCR showed that the WWP1 plasmids yielded a curve with the equation y = 1.0378x − 0.8771, resulting in an R2 of 0.9949. Similarly, the standard curve for the ACTB plasmids was y = 0.8835x + 3.1211, with an R2 of 0.9961. In comparison, the ddPCR method established in this study exhibited superior sensitivity and linearity. The standard curve for the WWP1 plasmids was represented by the equation y = 1.0232x − 0.0589, with an impressive R2 of 0.9998. For the ACTB plasmids, the standard curve equation was y = 1.0053x − 0.0272, also showing a high R2 of 0.9997 (Figure 4).

Higher reproducibility for plasmids detection with ddPCR

For the inter-batch reproducibility assessment, ddPCR demonstrated superior precision, with an average CV of 0.50% and 0.47% for ACTB and WWP1 plasmids, respectively. In contrast, RT-qPCR showed higher variability, with an average CV of 0.95% and 0.99% for ACTB and WWP1 plasmids, respectively. Compared with RT-qPCR, ddPCR had better repeatability and accuracy (Table 3, Table 4).

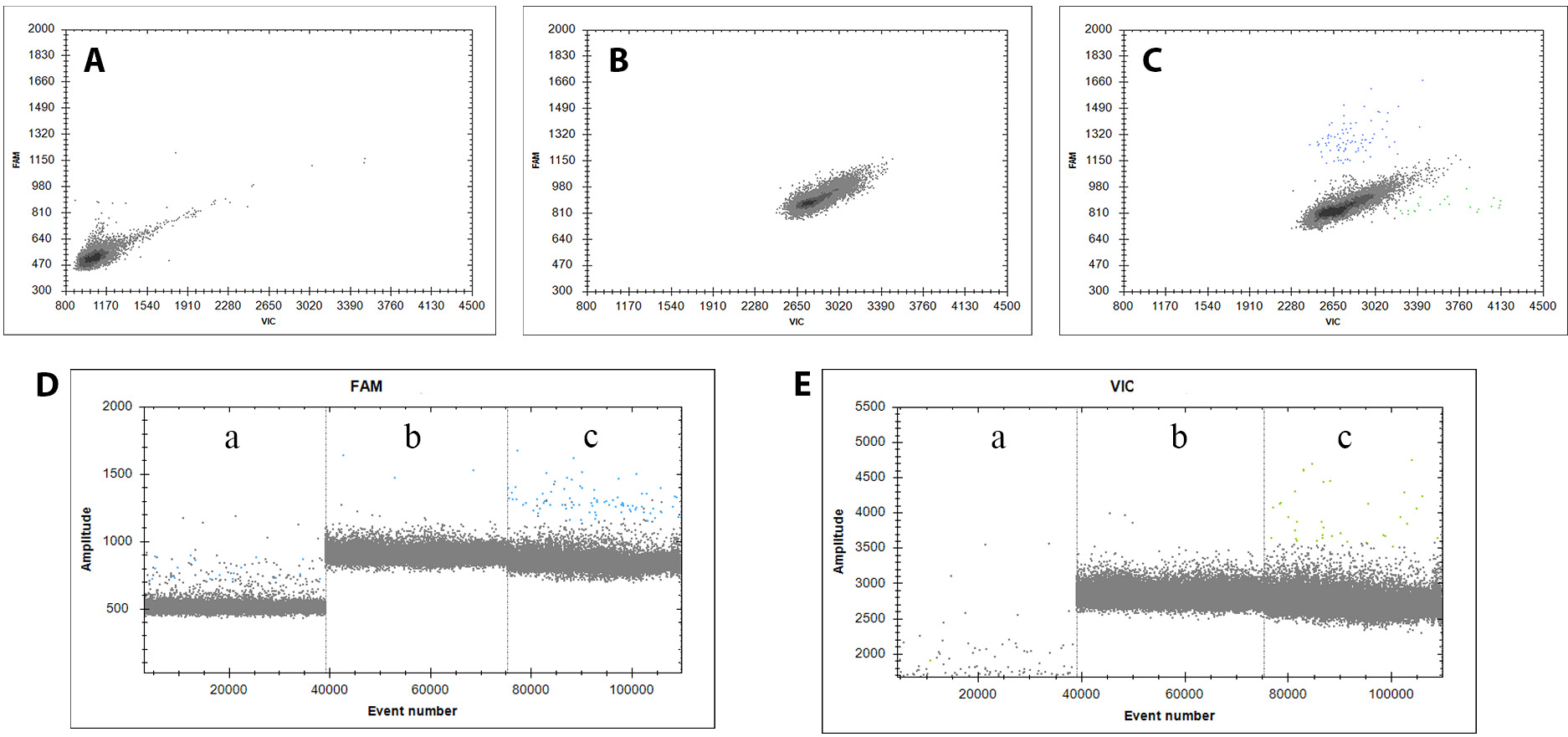

Linearization and restriction endonuclease treatment enhance eccDNA detectability

As shown in Figure 5, eccDNA detectability varied significantly across samples with different methods. Initially, eccDNA was almost undetectable in samples without linearization or restriction endonuclease digestion. This suggests that the presence of linear DNA may interfere with eccDNA detection, potentially affecting amplification efficiency and leading to inaccurate results. Following the removal of linear DNA and cleavage at the BsmI site, WWP1-eccDNA was consistently amplified and accurately detected in the samples. These results underscore the importance of removing linear DNA to preserve the integrity and accuracy of eccDNA amplification in our experimental setup.

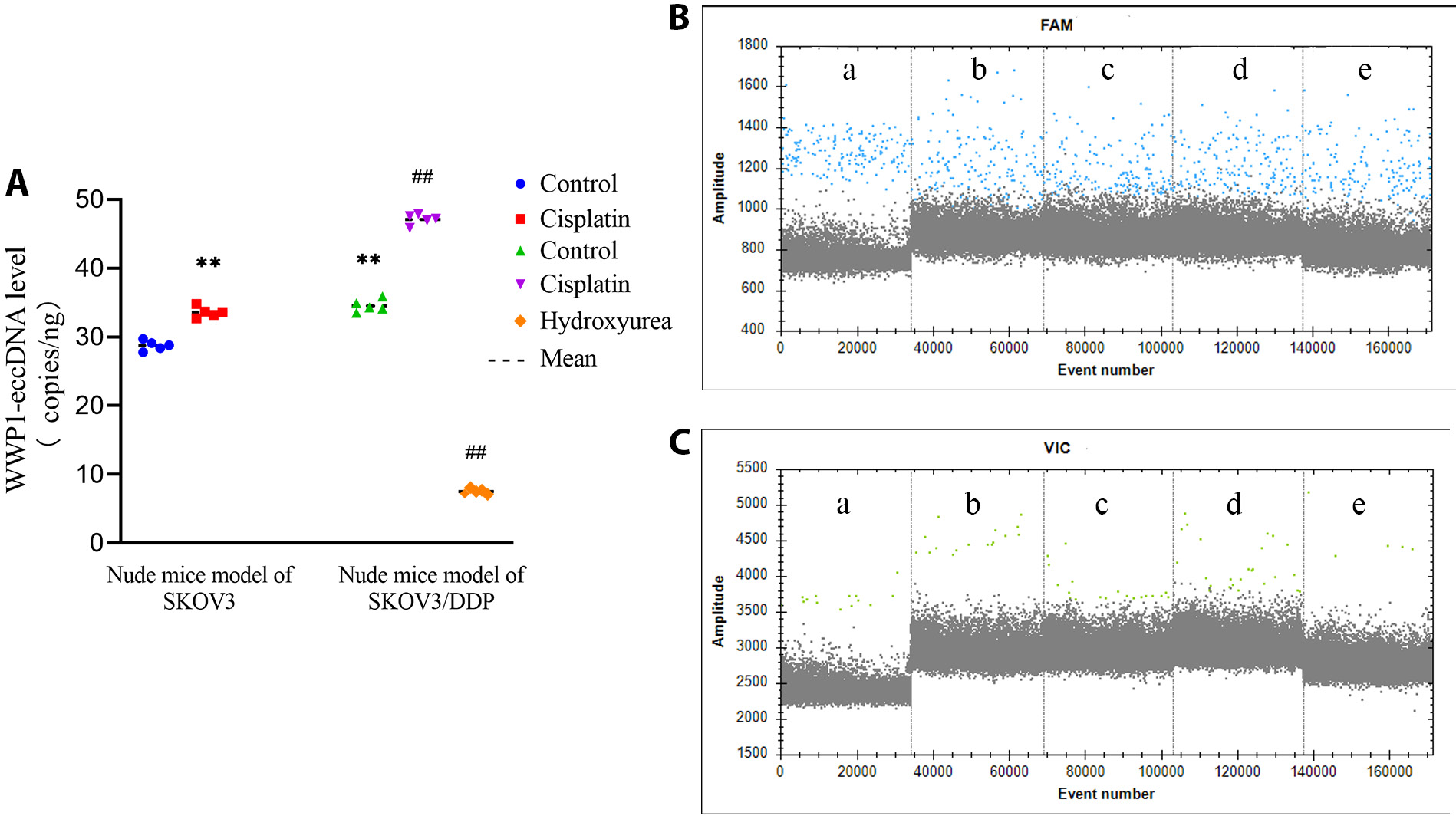

Cisplatin increases WWP1-eccDNA level

Digital droplet PCR analysis revealed notable differences in the copy numbers of WWP1-eccDNA across various treatment groups. Specifically, in the SKOV3 and SKOV3/DDP nude mice models, the cisplatin treatment significantly increased the copy number of WWP1-eccDNA compared to the control group. In contrast, the hydroxyurea treatment notably decreased WWP1-eccDNA levels in the SKOV3/DDP model. Additionally, the WWP1-eccDNA copy number in the control group of the SKOV3/DDP model was significantly higher than in the control group of the SKOV3 model (p < 0.01). These findings underscore the differential effects of cisplatin and hydroxyurea on WWP1-eccDNA abundance, indicating a potential mechanism through which these treatments modulate drug resistance profiles in the OC nude mice model (Figure 6, Table 5).

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to establish a highly sensitive and accurate ddPCR methodology for quantifying eccDNA copy numbers and to assess how different chemotherapeutic agents impact the copy number of WWP1-eccDNA in OC. The results of our linearity and reproducibility experiments unequivocally demonstrate that ddPCR outperforms traditional RT-qPCR in sensitivity and accuracy. Specifically, ddPCR achieved reliable detection of eccDNA at concentrations as low as 5 copies/μL, a marked improvement over RT-qPCR, which only provided consistent results starting at 100 copies/μL. These findings underscore the key advantages of ddPCR in oncological research, particularly when studying low-abundance genetic targets like eccDNA, which is pivotal in understanding tumor biology and resistance mechanisms.

Moreover, this study pioneers the application of ddPCR for the detection of genetic mutations in preserved clinical samples from asymptomatic individuals at high risk for OC.17 This innovative use of ddPCR holds considerable promise not only as a research tool but also for clinical applications, particularly in the early detection of genetic alterations associated with OC. By enabling the detection of low-level genetic markers in blood or other biosamples, ddPCR could facilitate early diagnosis and more timely therapeutic interventions, potentially improving patient outcomes.

Tumor MDR remains a critical challenge in cancer treatment, significantly affecting prognosis and treatment efficacy. Identifying and targeting novel molecular mechanisms involved in drug resistance is crucial for advancing therapeutic strategies. WWP1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase and proto-oncogene, is overexpressed or amplified in various cancers, including gastric, breast, liver, lung, and prostate cancers.7, 18, 19, 20 In these cancers, WWP1 primarily exerts its oncogenic effects by inhibiting the tumor suppressor PTEN, which leads to the activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway – an essential driver of MDR.21 These findings indicate that WWP1 may play a critical role in mediating drug resistance by modulating key signaling pathways that influence cell survival, proliferation and apoptosis.

In addition to its role in PTEN regulation, WWP1 has been shown to interact with miR-452, a microRNA involved in cancer cell migration and invasion, particularly in prostate cancer.22 This interaction further reinforces the multifaceted role of WWP1 in driving tumorigenesis and metastatic potential. In some hematological malignancies, such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML), WWP1 has been clearly identified as an oncogene. It can promote the progression of the cell cycle and help tumor cells evade apoptosis, thus maintaining the continuous proliferation of tumor cells.23 WWP1 is also involved in regulating other important cellular processes. During the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of tumor cells, WWP1 promotes the acquisition of mesenchymal characteristics by regulating the stability and activity of related proteins, thereby enhancing cell migration and invasion. This process contributes to tumor metastasis and drug resistance development.4 Given the central role of WWP1 in promoting cancer progression and MDR, developing inhibitors that target WWP1 could represent an effective therapeutic strategy to reverse drug resistance in cancer, potentially enhancing the efficacy of current chemotherapy regimens and improving clinical outcomes.

EccDNA, as a prevalent form of extrachromosomal genetic material, is implicated in the amplification of oncogenes and the regulation of tumor-associated genes. A recent study by Kim et al. conducted a comprehensive analysis of whole-genome sequencing data from 3,212 cancer patients, revealing that oncogenes are significantly enriched on eccDNA, particularly in cases involving gene amplification.24 This amplification is often associated with recurrent oncogenes and poor prognosis, indicating a strong link between eccDNA presence and increased tumor invasiveness. This widespread phenomenon across different cancer types further supports the potential importance of eccDNA in cancer biology.

Another key study highlighted the role of eccDNA in cross-resistance, especially through the amplification of the MYC oncogene.25 MYC, a key regulator of cellular processes such as growth and metabolism, is often amplified on eccDNA, contributing to resistance mechanisms that affect multiple chemotherapy drugs. The interaction between MYC and WWP1 is crucial in this context, as MYC-driven amplification of WWP1-eccDNA could significantly impact tumor resistance to chemotherapy. This underscores the importance of using ddPCR to evaluate the effects of different treatments on WWP1-eccDNA dynamics in cancer cells.

Hydroxyurea, a cell cycle-specific chemotherapeutic agent that inhibits nucleoside diphosphate reductase and prevents DNA synthesis during the S phase,26 was included in this study as a positive control. Research has shown that hydroxyurea can reduce tumor heterogeneity by eliminating eccDNA-containing MYC amplifications,27 bolstering its utility as a modulator of eccDNA expression. In this study, we observed that while cisplatin treatment increased WWP1-eccDNA levels, hydroxyurea treatment reduced them. This indicates that hydroxyurea’s ability to inhibit MYC-driven eccDNA amplification may contribute to reversing tumor resistance. These results provide insights into the differential impacts of chemotherapeutic agents on eccDNA biology and their potential to modulate drug resistance in OC.

Limitations

Despite its advantages in sensitivity and specificity, the ddPCR methodology used in this study has several notable limitations. The relatively high cost of consumables – such as fluorescent probes and droplet-generation chips – and the lower throughput compared to RT-qPCR may limit its feasibility for large-scale studies or routine use in resource-constrained clinical settings. Additionally, the linearization of circular DNA may be incomplete, leading to residual circular or partially linearized DNA species. To address these issues, future work will focus on optimizing reagent usage (e.g., reduced reaction volumes) and integrating automated platforms to enhance throughput. Collaborative efforts with clinical laboratories will also be prioritized to standardize protocols and improve technical proficiency.

Conclusions

Our study provides compelling evidence that WWP1-eccDNA plays a central role in mediating chemotherapy resistance in OC. The ability to accurately quantify WWP1-eccDNA levels using ddPCR presents new opportunities for monitoring drug resistance and assessing treatment efficacy. The enhanced sensitivity of ddPCR also has significant implications for early detection and monitoring of genetic alterations in cancer, offering a promising strategy for improving patient outcomes and advancing precision medicine in oncology. However, the current research is still at the animal model stage. In the future, further clinical data are needed to verify its broader applicability. Future studies should explore WWP1 inhibitors to reverse resistance. Clinically, ddPCR could monitor WWP1-eccDNA in liquid biopsies for early intervention, and our results indicate that targeting WWP1 and its associated eccDNA may offer a novel approach for overcoming drug resistance in OC.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as all data are already included in the manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.