Abstract

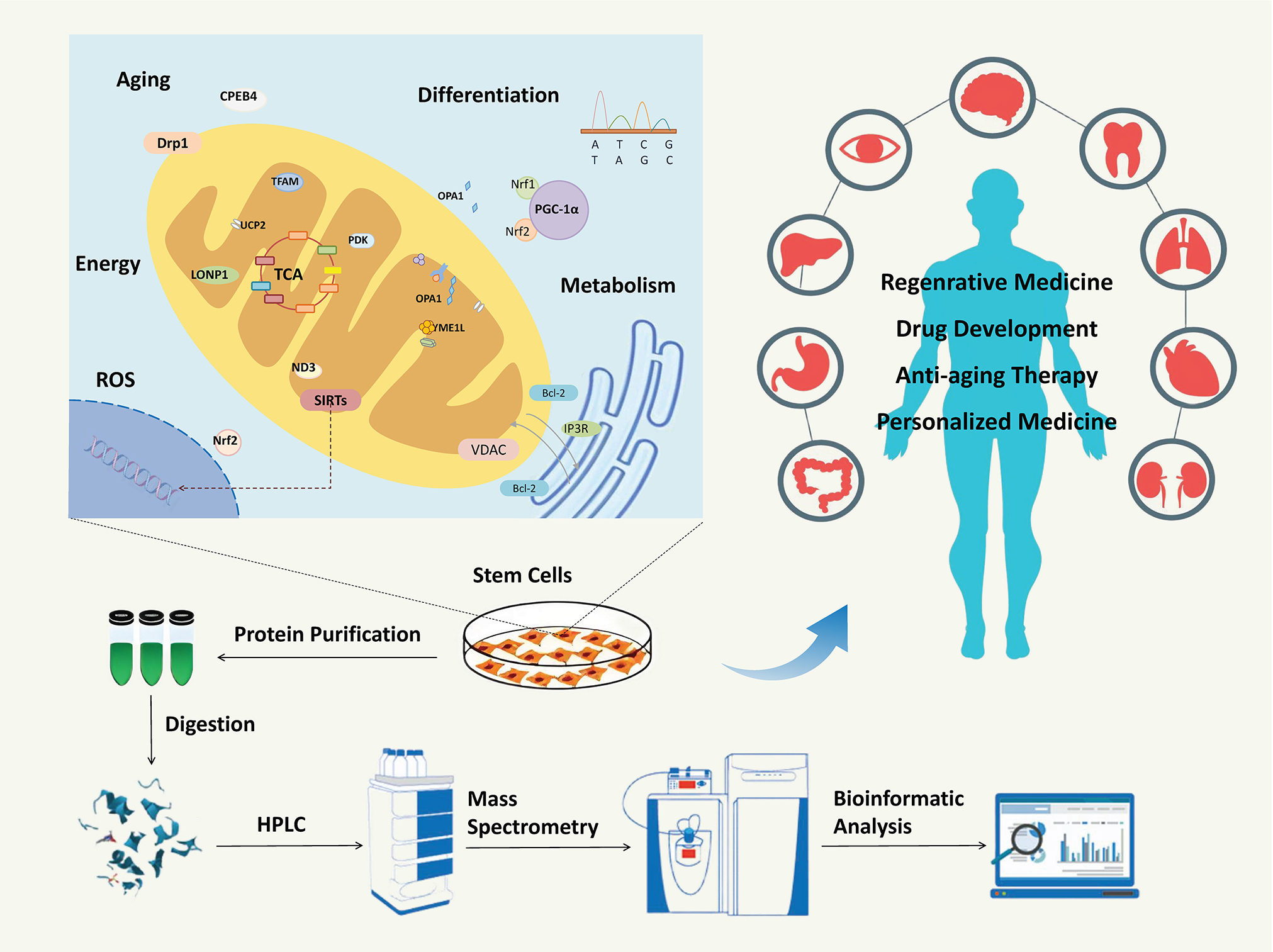

This review summarizes the latest advancements in stem cell (SC) mitochondrial proteomics. With the rapid development of biotechnology, mitochondrial proteomics has emerged as a pivotal area in SC research. The research methods used in mitochondrial proteomics include mass spectrometry (MS), with pre-MS sample processing, MS data acquisition employing both qualitative and quantitative approaches, and bioinformatics analysis to annotate and explore protein functions. In recent years, mitochondrial proteomics research has contributed to the establishment and expansion of our understanding of the roles of various mitochondrial proteins involved in regulating SC differentiation, metabolism and aging, including Drp1, Mfn1/2, OPA1, SIRT3, Bcl-2, YME1L, and PGC-1α. This multidisciplinary approach, combining qualitative and quantitative proteomics with bioinformatics, sheds light on the intricate regulatory mechanisms of mitochondrial proteins in SC. These findings provide a scientific basis for developing novel therapeutic targets and strategies, thereby advancing the field of regenerative medicine and personalized treatment paradigms.

Key words: stem cells, proteomics, mass spectrometry, mitochondria, bioinformatics

Introduction

Stem cells (SCs) are undifferentiated cells with self-renewal characteristics.1, 2 They can be classified by potency. Pluripotent SCs (e.g., embryonic SCs) can form tissues from all 3 germ layers.3 Multipotent SCs, such as hematopoietic SCs (HSCs), can differentiate into a restricted range of cell types within a specific lineage.4 Oligo-/unipotent SCs (e.g., spermatogonial SCs) generate only 1 or a few specific cell types.5 Biologically, their differentiation and proliferation are regulated by both genetic factors and external signals.6, 7 They can migrate to sites where they are needed, crucial for development and tissue repair. Additionally, many SCs can survive long-term, remaining in a quiescent state until activated. Due to their ability to generate diverse functional cells, SCs have become a major focus in modern biological and medical research. For example, in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, SC therapy has shown the effects of promoting neural regeneration, repairing damaged nerves, inhibiting inflammatory responses, and reducing neuronal apoptosis.8 For myocardial infarction, SCs succeed in reducing infarct size, abrogating adverse heart remodeling, and improving cardiac function.9, 10 In addition, the impressive therapeutic effects of SCs on vascular injury, corneal damage, osteoarthritis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and sepsis are also reported.5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Mitochondria are the dynamic cytoplasmic organelles with double-membrane structure. In addition to functioning as the cell’s “energy factory”, mitochondria play a crucial role in regulating calcium homeostasis, responding to oxidative stress, and controlling cell death. It is also the signal center for inducing gene transcription and post-translational regulation.15 Mitochondrial dysfunctions can occur due to a variety of factors. Mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) are a common cause of dysfunction. Since mtDNA encodes several essential proteins involved in the electron transport chain (ETC), which is critical for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, these mutations can lead to reduced ATP synthesis and an increase in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).16 Another contributor to mitochondrial dysfunction is defects in nuclear-encoded proteins, which constitute the majority of mitochondrial components. For instance, mutations in genes involved in mitochondrial protein import can prevent the proper assembly of mitochondrial complexes.17 Mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to the occurrence of various diseases. Congenital mitochondrial dysfunction is often manifested as mitochondrial myopathy or chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) in adults (where mitochondrial respiratory chain defects lead to muscle weakness due to energy deficiency18, 19) and Leigh syndrome in children with predominant central nervous system (CNS) symptoms. Beyond these, mitochondrial dysfunctions are also implicated in diseases related to the aging process. In Alzheimer’s disease, mitochondrial abnormalities lead to impaired bioenergetics and increased ROS production in neurons, which contribute to the accumulation of amyloid-β plaques and tau tangles.20, 21 In Parkinson’s disease, mitochondrial complex I deficiency is commonly observed, leading to dopaminergic neuron death.22, 23 Furthermore, the relationship between the SCs’ mitochondria and neurodegenerative diseases has been noticed by recent studies, which indicate the role of mitochondria as a main regulator of neural SC fates through redox modulation. Meanwhile, mitochondrial biogenesis, dynamics, or ROS scavenging can be impaired by abnormal metabolic products, such as amyloid-β peptide, which compromises SCs’ commitment, thereby exacerbating disease progression.24, 25, 26

Mitochondrial proteomics provides a holistic view of changes in protein composition, post-translational modifications and expression patterns. Through techniques such as two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry (MS), changes in the abundance of mitochondrial proteins can be detected. These findings can help elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms of the disease. Proteomics can also identify post-translational modifications (PTMs) of mitochondrial proteins, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination. For instance, altered phosphorylation patterns of mitochondrial proteins have been associated with changes in mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics.27, 28 By mapping these PTMs, proteomics can provide insights into how SCs mitochondrial functions are disrupted. Mitochondrial proteomics can also help in understanding the interactions between mitochondrial proteins. Proteomic techniques such as co-immunoprecipitation followed by MS can identify interacting proteins and how these interactions are affected in disease states. This knowledge may contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular events underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in SCs and could facilitate the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Objectives

This review summarizes the latest advancements in SC mitochondrial proteomics studies, including progress in sample processing, MS, data acquisition, and bioinformatics analysis. We aimed to advance our understanding of mitochondrial protein profiling technology and promote its applications in regenerative medicine and personalized therapy.

Research methods of mitochondrial proteomics

Mass spectrometry is an essential technology in proteomics research. It has become one of the most commonly used discovery and verification tools in the field of life sciences. The research methods of the MS-based technology mainly include pre-MS sample processing (mitochondrial extraction and purification), MS data acquisition and post-MS bioinformatics.

Sample processing

The conventional method for extracting mitochondria is differential centrifugation. During the extraction of mitochondria, it is necessary to pre-cool the equipment and maintain low temperatures throughout the homogenization process of tissues or cells to prevent protein denaturation and aggregation. Undissolved cells, cellular debris, and nuclei will first be removed by low-speed centrifugation (600 × g or 1,000 × g). Since mitochondria may be present in the flaky precipitate, resuspending the precipitate and performing 1 additional low-speed centrifugation can improve the mitochondrial yield. High-speed centrifugation (3,500 × g or 10,000 × g) was performed on the supernatant obtained from the low-speed centrifugation steps,29, 30 resulting in a crudely extracted mitochondrial precipitate, which has low purity and contains contaminants such as peroxisomes, endoplasmic reticulum and microsomes. Therefore, it can only be used for simpler applications, including analyzing the activity of certain mitochondrial enzymes and detecting mitochondrial morphology and apoptosis.

For mitochondrial proteomics, further purification is required. The sucrose density gradient centrifugation method has become a common method for mitochondrial purification due to its simple operation and low cost. It uses a sucrose buffer solution, which has a similar dispersion to the cytoplasm phase as the suspension medium and separates cell components of different densities in cell or tissue homogenates through gradient centrifugation.31, 32, 33, 34 However, sucrose of high concentrations has a high viscosity and high osmotic pressure, which can easily lead to repeated contraction and swelling of mitochondria. Several new density gradient media can purify mitochondria with intact morphology but are generally more expensive. Due to its low diffusion constant, Percoll® forms a very stable gradient that usually does not penetrate the biological membranes. Therefore, it minimizes the rupture of organelles and is commonly used for separating platelet mitochondria.35, 36, 37 Nycodenz contains sorbitol as an osmotic stabilizer. Due to its high density, low viscosity and minimal impact on osmotic pressure, the yield of intact mitochondria is significantly higher.38, 39, 40 As a dimer of Nycodenz, OptiPrep has the advantage of forming an automatic gradient in a short period.41, 42, 43

The disadvantages of traditional methods include: 1) reliance on costly ultracentrifugation equipment; 2) prolonged centrifugation causing mechanical damage to mitochondrial membrane; and 3) unavoidable contamination from cytoplasmic organelles, cellular debris and gradient medium, resulting in low sample purity. These shortcomings have brought about many limitations to mitochondrial proteomic research. Therefore, some researchers have attempted to use magnetic beads to sort mitochondria. Boussardon et al. used transgenic technology to induce the expression of biotinylated outer membrane protein OM64 in Arabidopsis thaliana mitochondria. After the plant tissue was lysed, it was incubated with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads for 1 min, exposed to a magnetic field for 2 min, and then washed 5 times after discarding the supernatant. The success rate, purity and integrity of mitochondrial sorting were significantly higher than those of density gradient centrifugation.44 Chen et al. achieved rapid sorting of mitochondria using immunomagnetic beads by constructing a fusion protein of mitochondrial outer membrane protein and tag protein, and detected the high-purity mitochondrial metabolites.45 However, these methods are only applicable to cell models and cannot be used for tissues and cells directly from humans or animals. Moreover, the knock-in of tag protein genes is time-consuming and labor-intensive, with a low success rate. Therefore, there is still a need to develop simpler, faster, less damaging and highly purified mitochondrial separation methods.

Mass spectrometry data acquisition

Qualitative mass spectrometric analysis

“Bottom-up” is a proteomic qualitative method that analyzes small peptide fragments directly. The basic process is to digest protein samples into a mixture of peptide segments and separate them with chromatography. Then, the peptide segments are fragmentated using MS, and the ion peak data from the fragmentation spectra is obtained to perform bioinformatics analysis. The identified peptide segments are then assembled into proteins through database matching to achieve protein identification. “Top-down” is another qualitative analysis experiment that enables global analysis on fragmented proteins. The intact proteins are separated from complex biological samples using separation techniques such as liquid chromatography (LC) or 2D gel electrophoresis. Then, techniques such as electron capture dissociation (ECD) are employed to allow low-energy free electrons to interact with protonated multi-charged protein or peptide ions. This interaction generates fragmentation during the exothermic phase. Protein identification is then achieved based on the fragmentation spectrum information and protein mass. Unlike enzymatic digestion-based methods, it can achieve high sequence coverage and retain the correlation information between multiple post-translational modifications. “Top-down” also has some drawbacks, such as difficulties in analyzing fragmented proteins in the gas phase. In contrast, “Bottom-up” involves enzymatically digesting proteins into peptide segments, making them easier to separate, ionize and fragment in the gas phase. As a result, “bottom-up” has become a more widely used method for proteomic qualitative analysis.

Quantitative mass spectrometric analysis

Quantitative proteomics is a method for precisely identifying and quantifying all proteins expressed by the genome or all proteins within a complex mixture system. It can be used to screen and identify the differentially expressed proteins between samples. Common quantitative methods include MS quantification, immunoassay and gene expression analysis.46 Mass spectrometry-based protein quantification methods can generally be divided into labeling and non-labeling techniques.47

The labeling method obtains peptide or protein quantification from the primary mass spectrometry (MS1) peaks of mixed samples with differential labeling.48 Currently, labeled quantitative proteomics methods can be divided into chemical labeling and metabolic labeling. Common chemical labeling methods include Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) and other isobaric peptide labeling methods.49, 50 These methods can generate isobaric MS1 peaks for multi-channel labeling. After the fragmentation of the isobaric peaks, different reporter ions are released during secondary mass spectrometry (MS2) and tertiary mass spectrometry (MS3) scans for relative quantitative analysis. Tandem Mass Tag labels the amino groups of peptides with 2, 6 or 10 isotopes. It compares the protein expression levels in different sample groups simultaneously by detecting the label intensities in MS. It has recently become a commonly used high-throughput screening technique in quantitative proteomics.49 Tandem Mass Tag allows multiple samples to be processed, labeled and analyzed in 1 batch with small errors, high parallelism and good stability. The iTRAQ refers to the use of 4 or 8 isotopic specific labels for the amino groups of peptides and the use of MS to detect label intensity for relative quantification of protein content.50 It offers strong separation capability, wide applicability, quantitative labeling, and high automation and accuracy. Billing et al. used ITRAQ-based MS to analyze the mitochondrial proteome of pluripotent FDCP-Mix cells and identify stage-and lineage-specific mitochondrial changes in hematopoietic progenitor cells. They linked the proteins in cellular differentiation with mitochondrial transport, fatty acid degradation and oxidative phosphorylation. This approach improved the efficiency of peptide identification.51

The metabolic labeling method Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Cultures (SILAC) uses 2 different isotopes, light or heavy, to label essential amino acids, which will be incorporated metabolically into cellular proteins. The protein is then identified and quantified using MS analysis.52 It can label living cells in vivo with a stable labeling effect and high efficiency. The requirement on sample amounts is low, and multiple proteins can be identified and quantified synchronously with small errors. However, it cannot be applied on tissue or fluid samples. Labeling in animal models is usually too costly to perform.

Label-free technology is a protein quantification method that does not rely on isotopic labeling. Based on the intensity of the parent ion of the peptides, it calculates the signal intensity of each peptide segment on liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC-MS-MS) for relative quantification.53 First, the sample to be tested is digested into peptide segments. Then, the digested sample is analyzed using a mass spectrometer to quantify the protein by detecting the mass and abundance of the peptide segments in the sample. In label-free technology, the capturing frequency of peptides in MS is considered to be positively correlated with the abundance in the mixture. Therefore, an appropriate mathematical formula can link the count of peptide segments in MS to the amount of protein in samples. Compared with traditional labeling methods, label-free technology has the advantages of simple operation, high throughput, high sensitivity, and high applicability,53 and thus has been widely used in proteomic research.

Additionally, based on the Data Independent Acquisition (DIA) mode, sequential windowed acquisition of all theoretical fragment ions (SWATH) has become a new technology that can also perform on label-free samples.54 It divides the entire scanning range of MS into several intervals, sequentially performs high-speed MS1 scans on all peptide precursor ions within each mass range, and then collects MS2 fragment ion data for relative or absolute protein quantification.54 Detection accuracy of SWATH surpasses traditional label-free approaches. It has superior identification performance on low-abundance proteins and peptides, fewer restrictions on sample quantity, complete and comprehensive data retention, good reproducibility, and high traceability. However, SWATH has much higher requirements for analysis algorithms than labeled techniques.

Bioinformatics

Based on qualitative and quantitative proteomics techniques, bioinformatics research can explore the potentially related processes and involved mechanisms by annotating differentially expressed proteins in samples with Gene Ontology (GO; http://www.geneontology.org), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; https://www.

kegg.jp) pathway, and Protein–Protein Interaction Networks (PPI; https://cn.string-db.org).

Gene Ontology is an internationally standardized gene function classification system that provides a dynamic and controllable vocabulary to comprehensively describe the attributes of genes and gene products in organisms. It consists of a set of predefined GO terms that define and describe the functions of gene products. The GO annotations library mainly provides annotations for GO terms. The KEGG database is a database that systematically analyzes the metabolic pathways of gene products in cells and the functions of these gene products. This database helps to study genes and expression information as a whole network. It integrates data from genomes, chemical molecules and biochemical systems, including metabolic pathways (PATHWAY), drugs (DRUG), diseases (DISEASE), gene sequences (GENES), and genomes (GENOME). The PPI is formed by proteins interactions that participate in various aspects of life processes such as signaling, gene expression, energy metabolism, and cell cycle regulation. Constructing an interaction network of differentially expressed proteins can help us discover the trends of change and key protein nodes at the proteomic level.

The comprehensive utilization of qualitative and quantitative strategies in mitochondrial proteomics, combined with in-depth bioinformatics analysis, possesses significant scientific value in research. It can help discover the influence of mitochondrial proteins on SC biological processes, including self-renewal, differentiation and aging, thereby providing insights into the relationship between mitochondria and clinical status, such as cancer, cardiovascular and neurological disease.55 Based on the establishment of a SC mitochondrial protein database, this multi-faceted research approach will not only unravel the functional architecture underlying mitochondrial proteome complexity but also promote the new therapeutic strategies development for personalized and regenerative medicine.56, 57, 58

The role of mitochondrial proteins in stem cell differentiation

Mitochondrial dynamics is an important part of SC physiology and can have a profound impact on SC fate by regulating mitochondrial morphology and function. Some key proteins related to mitochondrial dynamics are members of the dynamin-related protein family that function as GTPase. They have large molecular weights and include dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), mitofusin 1/2 (Mfn1/2) and optic atrophy protein 1 (OPA1).59, 60 Drp1, as a key mitochondrial fission protein, plays an important role in modulating mitochondrial morphology and function. Studies have shown that Drpl inhibition will lead to mitochondrial elongation and increase its bioenergetic efficiency.61 Mfn1/2 is a key protein for mitochondrial outer and inner membrane fusion. Lack of Mfn1/2 leads to decreased ATP levels and slower SC growth. The OPA1 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that plays a central role in the precise regulation of mitochondrial fusion and fission. It exists in 2 main forms: transmembrane long form (L-OPA1) and soluble short form (S-OPA1). The long form of OPA1 anchors to the inner mitochondrial membrane, while the short form is released from the inner membrane via proteolysis. The OPA1 responds to changes in membrane potential through the ratio of its isoforms, and this isoform cleavage behavior is activated under depolarization conditions, leading to the transition from L-OPA1 to S-OPA1. This process is crucial for maintaining the stability and morphology of the mitochondrial network.62 In addition, OPA1 also directly participates in the regulation of mitochondrial cristae morphology, which further regulates the function of the ETC and ATP synthesis capacity by affecting the structure and number of cristae, thereby affecting the energy state and differentiation potential of SCs.63

Besides Drp1, Mfn1/2 and OPA1, there are some other mitochondrial proteins and related transcription factors that play important roles in regulating SC energetics and influencing cellular lineage commitment.64, 65 As a mitochondrial deacetylase, SIRT3 can affect SC differentiation by directly regulating a variety of key enzymes involved in mitochondrial energy metabolism through deacetylation.66 PGC-1a is a transcriptional co-activator that can induce mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration, thereby improving cellular metabolic reprogramming. In pluripotent SCs, overexpression of PGC-1α has been shown to activate transcription factors such as Nrf-1 and 2, which can promote mitochondrial protein synthesis and functional optimization, thereby increasing mitochondrial gene expression and respiratory chain activity, inducing differentiation into specific cell types, such as neural precursor cells.65

Mitochondrial proteins that induce apoptosis also play an important role in SC development reprogramming. During the self-renewal of SCs, anti-apoptotic proteins in the Bcl-2 family (e.g., Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, and Mel-1) are highly expressed.67 These proteins inhibit apoptosis by preserving mitochondrial membrane integrity.67 This mechanism maintains stemness and supports cellular diversity. On the other hand, Bax, as a pro-apoptotic protein in the BCL-2 family, is generally present in the cytoplasm. After being activated, it will translocate to the surface of mitochondria to form a pore across the membrane, leading to a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, an increase in membrane permeability, and the release of apoptotic factors.68 These changes ultimately promote SC apoptosis, eliminating redundant or misprogrammed cells during development.

Mitochondrial proteomics can provide important help for us to better understand the differentiation regulation mechanism of SCs. Researchers used proteomics and metabolomics approaches to reveal the key role of mitochondrial proteins in the differentiation process of neural SCs and progenitor cells.69 By analyzing the state transitions of neural stem and progenitor cells (NSPCs) between rest and activation, researchers found that significant changes in 5 mitochondrial proteases (including YME1L, PITRM1, METAP1D, LACTB, and HTRA2) have a significant impact on cellular energetics. Particularly, YME1L plays a crucial role in maintaining the resting state with fatty acid oxidation as the main energy source. The deletion of YME1L triggers differentiation programs, leading to irreversible transitions to other metabolic states. These findings provide a new perspective for understanding the fate determination of SCs and provide potential targets for future therapeutic strategies. Shekari et al. used subcellular proteomic methods that combined subcellular separation with MS techniques to identify 3,183 proteins associated with mitochondria, rough endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus, and microsomes in human embryonic SCs (hESCs).70 Among these proteins, a total of 160 differentially expressed proteins were enriched in multiple signaling pathways. Meanwhile, it was also found that Bax protein has a specific localization in the subcellular structure Golgi apparatus in hESCs, and can rapidly translocate to mitochondria and initiate apoptosis programs when hESCs DNA is damaged.70 Therefore, Bax’s rapid response and translocation ability may be a key factor in regulating apoptosis in hESCs, and may directly affect the self-renewal and differentiation potential of SCs.

Mitochondrial proteins and energy metabolism of stem cells

Mitochondria are the main sites of cellular energy metabolism. In undifferentiated SCs, mitochondria usually exhibit immature morphology, featuring the spherical structure and short cristae of mitochondria, which can provide a much larger surface area to increase the efficiency of ATP synthesis to meet the energy requirements of SCs. At this time, glycolysis is the main metabolic pathway for mitochondria. Some key mitochondrial proteins play a crucial role in the energy metabolism and stemness maintenance of SCs: 1) Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) protects SCs from ROS-induced damage by establishing proton leakage across the inner mitochondrial membrane and reducing oxidative phosphorylation efficiency71; 2) ATPase inhibitor (IF1) directly inhibits the activity of ATP synthase to ensure that SCs maintain a high rate of glycolysis72; 3) Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) inhibits the phosphorylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) to convert pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, effectively limiting pyruvate’s entry into the tricarboxylic acid cycle.73 These mitochondrial proteins synergistically provide energy and maintain stemness through metabolic regulation.

In differentiated SCs, mitochondria have a complex inner membrane system and abundant cristae structures. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) is a protein complex between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes, and its subunits are primarily composed of pore-forming proteins such as voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT) and cyclophilin D (CyP-D). Some specific physiological or pathological conditions, such as Ca2+ concentration stimulation and oxidative stress, can activate CyP-D and cause the mPTP channel to open, which leads to a sharp increase in mitochondrial membrane permeability and activating oxidative phosphorylation.74, 75 Appropriate mPTP opening can help maintain the stability of the intracellular environment and promote the smooth differentiation of SCs into specific cell types. Hu et al. reported that transferring functional mitochondria via extracellular vesicles from mouse mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to damaged pancreatic cells restored mPTP-related protein function, cellular energy metabolism and ATP supply.74 However, excessive mPTP opening may lead to SC apoptosis and affect the differentiation process. In the induced pluripotent SC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) from patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), mPTP was found to have excessive opening and related to the upregulated oxidative stress.75 By suppressing excessive mPTP opening, the cellular energetics of iPSC-CM can be improved with alleviate oxidative stress.75

Mitochondrial Lon protease 1 (LONP1) is a mitochondrial matrix protease that plays an important role in mitochondrial function maintenance and protein quality control. It is involved in fatty acid oxidation and degradation of damaged or misfolded mitochondrial proteins. In addition, LONP1 regulates mitochondrial DNA replication and transcription, affects respiratory chain protein synthesis, and is essential for energy metabolism in human iPSCs.76 During the process of iPSCs differentiation into cardiomyocytes, the upregulation of LONP1 activity helps to orchestrate the metabolic shift from glycolysis to fatty acid oxidation, ensuring the balance between glucose and fatty acid oxidation. LONP1 deficiency may induce mitochondrial dysfunction, impairing cardiomyocytes’ energy production and cardiac function.76 These findings highlight the importance of LONP1 in maintaining energy metabolism and mitochondrial function during SC differentiation and help to understand the underlying mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction-related diseases.

Mitochondrial proteomics is of great significance for studying the relationship between mitochondrial proteins and SC bioenergetics. Retinoblastoma 1 (RB1) is one of the best known tumor suppressor genes.77 Recent studies have shown that it promotes mitochondrial energy metabolism through the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) pathway during the differentiation of iPSCs into cardiomyocytes.78 Using specific RB1 gene knockout and TMT-labeled quantitative proteomics techniques, researchers analyzed the effects of RB1 deletion on mitochondrial proteins in adult mouse colon and lung tissues. By analyzing samples from 6 mice of each genotype, a total of 8,063 proteins were identified. Among them, mitochondrial proteins associated with the respiratory chain and OXPHOS were significantly downregulated. Moreover, the mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate, mitochondrial mass and the mitochondrial-to-nuclear DNA ratio all decreased.79 This result unveils a new role of RB1 in maintaining mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, which could inform the development of therapeutic strategies for mitochondrial dysfunction-related diseases.

Mitochondrial protein and stem cell aging

With age, the function of SCs gradually declines. Mitochondrial proteins play an important role in this process. Some studies have shown that oxidative damage and abnormal expression of mitochondrial proteins are closely related to SC aging. For example, with the help of cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), SIRT3 can catalyze the deacetylation of mitochondrial proteins, coordinate metabolic responses to oxidative stress and fluctuating energy demands, and maintain mitochondrial health.80 In HSCs, SIRT3 is highly expressed, whereas in differentiated hematopoietic cells, its expression is suppressed. Studies have shown that the loss of SIRT3 may cause the loss of quiescent state in HSCs, while overexpression of SIRT3 may improve aging HSCs function. Therefore, SIRT3 may become a potential target for anti-aging therapy in SCs.81

There are multiple critical connections between mitochondrial homeostasis and SC aging, involving multiple proteins and signaling pathways. Autophagy-related proteins, such as Beclin1, p62 and LC3, play a key role in maintaining mitochondrial function and SC vitality by clearing damaged mitochondrial components.82 Mitochondrial fusion and fission-related proteins, such as Mfn1/2, and Drp1, are crucial for maintaining the normal morphology and function of mitochondria.83 Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) is involved in maintaining the stability of mitochondrial DNA, which has an important impact on SC aging.84 Additionally, the ROS scavenging system, as well as the mTOR signaling pathway, also plays key roles in regulating SC growth, metabolism, survival, and function by affecting mitochondrial protein homeostasis.85

Mitochondrial proteome analysis can help us further evaluate the role of the above proteins and pathways in SC aging and may provide new strategies for delaying SC aging. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 4 (CPEB4) is an RNA binding protein that can bind to the polyadenylation element sequence of target RNA to regulate the translation. Through immunoprecipitation combined with RNA sequencing technology, researchers found that CPEB4 can specifically bind to messenger RNA encoding mitochondrial proteins in SC,86 indicating that CPEB4 may regulate mitochondrial proteomic activity by regulating mitochondrial translation. By performing low-input mass spectrometric analysis of adult muscle SCs at different aging stages in mice, 368 mitochondrial proteins associated with CPEB4 were identified, revealing their significance in SC energetics and aging. To test whether the restoration of CPEB4 expression can reverse the cell cycle stagnation in aged SC, researchers conducted experiments in a mouse muscle transplantation model and demonstrated that increasing CPEB4 levels in aged SCs alone was sufficient to rescue their regenerative capacity and promote the formation of new muscle fibers.86

Mitochondrial proteins and ROS

Reactive oxygen species are a class of oxygen-containing substances with high reactive activity that play a role in signal transduction between mitochondrial and cellular communication. During oxidative phosphorylation under physiological conditions, electrons are transferred through the ETC on the inner membrane of mitochondria, and some electrons leak out before reaching the terminal oxidase and reducing oxygen molecules to produce ROS. Maintaining appropriate levels of ROS is crucial for the function of SCs. Suppressing ROS in neural or hematopoietic SCs below physiological levels can significantly reduce their regenerative potential, manifested by impaired proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal abilities.61, 87

When cells are under various pathological conditions, such as hypoxia, aging or chemical inhibition of mitochondrial respiration, the rate of mitochondrial ROS production increases, inducing mitophagy and affecting SC signaling pathways.88 The KEAP1-Nrf2 pathway is important for antioxidation. By detecting the binding site of KEAP1, Zeb et al. found that only phosphoglycerate mutase 5 (PGAM5), a mitochondrial serine-threonine protein phosphatase, responded to moderate mitochondrial ROS production and accumulated to induce PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy.88 Nrf2 protects the heart from oxidative damage and plays an antioxidant stress role in skin diseases.89 Koch et al. demonstrated impaired Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress response and reduced mitochondrial protein abundance in atopic dermatitis.90 These findings suggest that KEAP1-mediated regulation on cellular ROS levels acts as a negative feedback mechanism, enabling excessive ROS to be cleared by mitochondrial autophagy.

Mitochondrial proteomic research helps to further understand the pathogenesis of oxidative stress injury and reveal potential intervention targets. Ginsenoside Rb1 (GRb1) is a protopanaxadiol isolated from the root of Panax ginseng, which plays an important role in inhibiting apoptosis and stabilizing mitochondrial function. In a proteomic analysis of ischemic myocardial SCs, the NADH dehydrogenase subunit of mitochondrial complex I was identified as a GRb1-regulated effector protein, primarily through reduced complex I-dependent oxygen consumption and inhibited enzyme activity.76 Furthermore, Venkatesh et al. found that GRb1 binds to the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 3 (ND3) subunit, trapping mitochondrial complex I in an inactive form. This interaction reduces NADH dehydrogenase activity and ROS production, significantly alleviating myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury.76

Clinical application of stem cell mitochondrial proteomics

Regenerative medicine and stem cell therapy

Regenerative medicine is an emerging field in health science research that focuses on generating and developing specific functional biological substitutes to restore, replace, or improve tissue and organ function. With no immune suppression and reduced toxicity, it can avoid the huge costs incurred by lifelong anti-rejection therapy. Recently, organoid culture technology has gradually emerged. It can construct three-dimensional (3D) cellular structures resembling real human organs, providing a valuable platform for disease modeling and drug screening.

Stem-cell-based therapies, including human PSCs and MSCs, are central to regenerative medicine. The mechanism of SC-mediated mitochondrial transfer shows clinical potential. For example, iPSC-derived mesenchymal SCs have been shown to treat neuronal damage post-cerebral infarction through the mitochondrial delivery mechanism.91 In addition, MS and bioinformatics analysis are now used to study traditional Chinese medicine’s (TCM) effects on mitochondrial proteomics in lung MSCs, aiming to identify new targets and approaches for pulmonary fibrosis.92, 93

Mitochondrial proteomics also contributes a lot to the identification of key biomarkers of signaling pathways and is crucial for understanding the behavior of cells and organoids in various therapeutic environments. In a COVID-19 study, RNA sequencing and proteomic analysis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) proteins revealed a differential protein: The mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS).94 Enhancing MAVS expression in MSCs via electroporation (to improve plasmid transfection efficiency) increased interferon production and innate immune response, reduced viral distribution, and offered a potential new COVID-19 treatment strategy.94

Drug development and disease treatment

The study of mitochondrial proteome can also provide new ideas for drug development and disease treatment. By analyzing the role of mitochondrial proteins in the occurrence and development of diseases, we can not only screen potential therapeutic drugs and reveal their mechanisms of action but also evaluate drug efficacy and safety. Using proteomic technology, clinicians can monitor the changes in mitochondrial proteome in patients after treatment, and judge the efficacy of drugs and potential adverse reactions. This process is crucial for drug selection and dose adjustment in personalized medicine. For example, the proteomic analysis identified a new acute myeloid leukemia subtype (Mito-AML) dependent on mitochondrial complex I and sensitive to venetoclax, a small molecule Bcl-2 inhibitor that disrupts mitochondrial OXPHOS to induce apoptosis.95 Studies based on mitochondrial proteomics also highlight endogenous/exogenous mitochondrial-targeted molecules, which show promising hope for clinical application. Resveratrol, e.g., enhances SC survival under oxidative stress by regulating mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy.96, 97 Understanding these molecules’ effect on mitochondrial function and cellular biological processes aids in the design of more effective drugs.

Anti-aging treatment

Mitochondrial proteomics is a powerful tool for anti-aging research, especially for studying SC energetic disorders and aging-related diseases. It not only helps to reveal the mechanism of targeted mitochondrial proteins (e.g., CPEB4), but also provides new strategies for mitochondrial transfer and anti-aging drug development. Through untargeted proteomics analysis, Zhao et al. revealed that mitochondrial proteins spontaneously released by NSCs were significantly enriched in extracellular vesicles (EVs).84 Morphological and functional analysis confirmed the presence of ultrastructurally intact mitochondria in EVs, maintaining membrane potential and respiratory activity. Transferring these mitochondria from EVs to NSCs with mitochondrial DNA defects can rescue mitochondrial function and increase the survival rate of SC.84 This mechanism provides a new therapeutic strategy for multiple sclerosis and neural degeneration diseases. Other proteomic studies have found the potential of bone marrow MSC-derived EVs in anti-aging therapy, especially in preserving mitochondrial function. All these findings underscore the critical role of proteomics in understanding SC anti-aging mechanisms and advancing SC-based therapeutic strategies, especially for diseases involving mitochondrial damage.

Personalized medicine

Personalized medicine, also known as precision medicine, is a medical model that integrates multi-dimensional biological information (e.g., genomics, proteomics and metabolomics) to design optimal treatment plans tailored to individual patients. Its goal is to maximize the therapeutic effect and minimize the adverse effects. The core principles include precise diagnostic testing and customized interventions based on patient’s unique molecular profiles.

Current applications of personalized medicine primarily focus on identifying genetic variations and developing personalized treatment strategies, particularly in oncology.57, 98 It also encompasses omics-based approaches for disease risk assessment, drug response prediction, and treatment outcome optimization.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) have attracted wide attention as a distinct cell population within tumors, critically involved in tumorigenesis, progression, recurrence, and treatment resistance. Integrating multi-omics analysis, especially mitochondrial proteomics, provides new insights into the intrinsic molecular mechanisms of CSCs. In a study by Skvortsov et al., CSCs were isolated and enriched from patient tumor tissues using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS), laser microdissection, and 3D culture methods.98 Subsequent proteomic profiling of mitochondrial protein expression identified specific surface markers (e.g., CD44, CD24, CD133, ALDH), which reflect the energy metabolism and functional status of tumor cells.98 This approach is crucial for understanding tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment dynamics.

In clinical practice, SC mitochondrial proteomics shows promise for disease diagnosis and classification. Analysis of patient mitochondrial proteomes can enhance early diagnosis and accuracy, refine disease subtyping, and guide personalized treatment. Diseases-specific alterations in the mitochondrial proteome (e.g., in neurodegenerative diseases,99 cardiovascular diseases4 and cancers57) can serve as biomarkers. For instance, detecting mitochondrial proteins linked to proliferation, apoptosis or metabolic abnormalities in SCs can aid clinicians in diagnosing disease subtypes, assessing disease severity, and tailoring treatment more accurately. This can help improve therapeutic outcomes, reduce adverse reaction risks, and optimize patient care. Thus, SC mitochondrial proteomics holds significant potential in personalized medicine and may become a cornerstone of future clinical practice.

Limitations

First, it remains unclear whether different sample preparation techniques (e.g., density gradient centrifugation vs magnetic beads isolation) or protein quantification methods (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ and SILAC) exhibit different efficiency in detecting signaling pathway proteins in SCs. Second, the sensitivity of current techniques may not be sufficient to detect low-abundance proteins that might be involved in key processes such as SC self-renewal, differentiation and apoptosis. This limitation could result in an incomplete characterization of the mitochondrial proteome. Third, standardized protocols for SC mitochondrial proteomics are lacking. Most research groups employ custom methods for sample collection, preparation and data analysis, leading to inconsistencies that hinder cross-study comparisons and impede comprehensive understanding. Fourth, future studies should critically compare existing SC proteomics datasets to assess the presence or absence of specific signaling pathway proteins. Finally, clinical studies are needed to verify the biological roles of specific proteins implied by the SC mitochondrial proteomics. Addressing these limitations is essential to establish the methodology’s applicability in answering specific biological questions and advancing SC research.

Conclusions

As a focal point in current life sciences, mitochondrial proteomics provides critical insights into the roles of mitochondrial proteins in SC differentiation, energy metabolism, and aging. These discoveries drive progress in regenerative medicine, anti-aging therapies, drug development, and bioengineering innovations. Advances in protein detection technology, deeper mechanistic studies of SC signaling pathways, expanded clinical trials and interdisciplinary collaborations will accelerate the clinical translation of mitochondrial proteomics.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.