Abstract

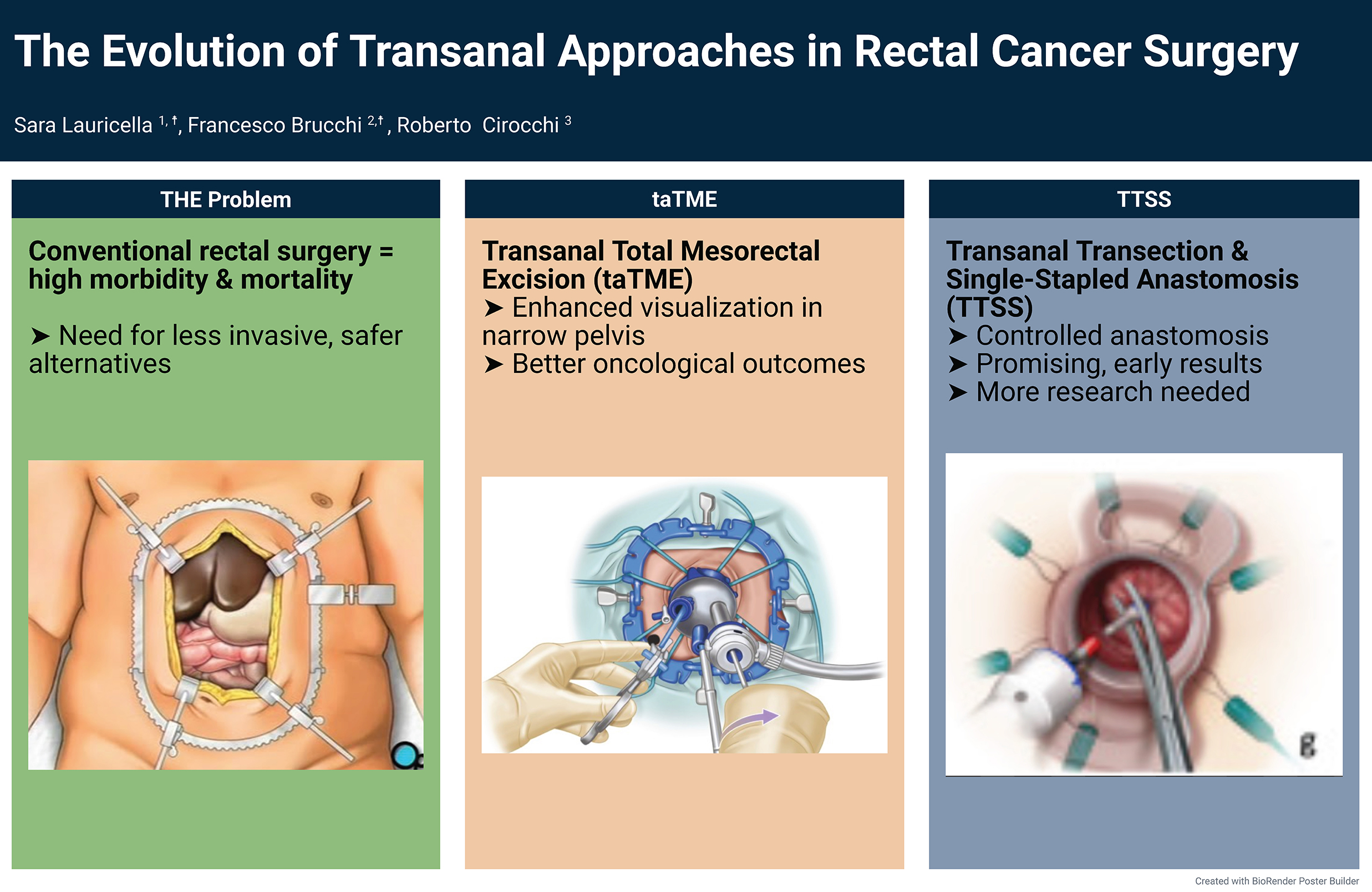

Minimally invasive techniques are progressively transforming colorectal (CRC) surgery. Given the high mortality and morbidity rates associated with conventional surgical treatments for CRC, the development of less invasive alternatives is crucial. The long-established use of transanal platforms for local excision of early-stage rectal cancers paved the way for the development of a transanal approach to total mesorectal excision (TME). Transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) has emerged as a novel technique for treating low CRC, offering superior and more accurate visualization of the presacral mesorectal plane compared to the abdominal approach, and providing particular advantages in the narrow male pelvis. The current data on oncological and functional outcomes are promising. The transanal transection and single-stapled anastomosis (TTSS) approach represents the latest advancement in transanal techniques for treating low CRC. Evolving from taTME, it provides a more controlled and potentially safer anastomotic technique. However, the data are still preliminary, and larger studies are needed to validate its effectiveness. This review explores the evolution of minimally invasive and transanal surgical techniques for low CRC treatment, comparing outcomes across various approaches with a focus on patient selection criteria and oncological results.

Key words: rectal cancer, transanal excision, transanal endoscopic surgery, transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME), transanal transection and single-stapled anastomosis (TTSS)

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) poses a significant global health challenge due to its high incidence and mortality rates,1 making it one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Effective management of CRC requires a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to ensure the best possible outcomes for patients. Recently, the management of early CRC has progressed considerably, driven by advancements in diagnostics, surgical techniques and multimodal therapies.2 When treated appropriately, the prognosis for patients diagnosed with stage I rectal cancer is generally favorable, with 5-year survival rates exceeding 90%.3

Local excision has been fundamental for select early-stage rectal tumors. Transanal local excision (TAE) was initially used as a minimally invasive method to remove small lesions. However, as technology advanced, novel approaches such as transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), transanal endoscopic operation (TEO) and transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) emerged. These techniques build upon TAE and have significantly enhanced surgical precision, visualization and access, while reducing patient morbidity and improving postoperative outcomes.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 By combining the benefits of local excision with oncological results comparable to those of more radical surgeries, these techniques offer a promising alternative for select patients with early-stage CRC.9 However, these advanced techniques require highly specialized training and expertise, and not all centers have the necessary equipment or experienced surgeons to perform these procedures effectively. Additionally, appropriate patient selection remains crucial for achieving optimal outcomes.

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) has further pushed the boundaries of minimally invasive surgery by eliminating external incisions and reducing associated risks such as wound infections and hernias.10 Initially developed in animal models, NOTES has been explored through various natural orifice routes.11, 12 Although its clinical application is still considered experimental, it holds considerable potential for future therapeutic use. Meanwhile, hybrid approaches like transanal total mesorectal (taTME), which builds on the principles of the Transanal Abdominal Transanal Proctosigmoidectomy (TATA) technique, have shown promise in offering safe, precise and minimally invasive alternatives for CRC surgery.13 The development of taTME has been driven by the need to enhance visualization and access within the deep and narrow pelvic cavity – an anatomical region that poses significant challenges for traditional laparoscopic or open surgical approaches. The pioneering work of Sylla et al.14 has paved the way for a more targeted and effective approach to CRC resection. By combining transanal and transabdominal approaches for mesorectal dissection (the precise removal of rectal tissue and surrounding lymphatics), taTME addresses limitations of conventional transabdominal total mesorectal excision (TME). This dual approach enables more precise dissection, improved visualization of critical pelvic anatomy and tighter control of distal resection margins (the cut edge closest to the anus).15

A recent advancement in transanal approaches for low rectal tumors is transanal transection and single-stapled anastomosis (TTSS). Introduced in 2019, TTSS was designed to overcome the limitations of earlier transanal methods by balancing oncological efficacy with functional outcomes. Although TTSS appears promising, the available data remain preliminary.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are twofold. First, to map the historical evolution of transanal surgical techniques used in the management of rectal tumors. Second, to compare contemporary transanal approaches – including TEM, TEO, TAMIS, taTME, and TTSS – with respect to morbidity, recurrence rates and survival outcomes.

Methodology

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library databases. The search strategy used a combination of free-text terms and MeSH terms. Key search terms included: “transanal,” “rectal cancer,” “early-stage rectal cancer,” “transanal excision,” “transanal endoscopic surgery,” “TEM,” “TEO,” “TAMIS,” “taTME,” and “TTSS.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) were applied to combine these terms. No date limit was applied, and studies published up to January 2025 were included. Studies were included if they were original research, written in English and focused on transanal surgical management of CRC. There were no limitations on the number of participants or the age of patients. Exclusion parameters included studies on non-surgical treatments, studies not available in full text and articles unrelated to the topic of transanal surgical techniques for CRC. Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts and reviewed full texts to assess eligibility based on predefined criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or, if necessary, by consulting a 3rd reviewer. Data were collected on various aspects, including general disease information, surgical details (e.g., type of procedure, surgical approach, instrumentation) and outcomes (e.g., morbidity, complication rates, recurrence rates, etc.). The most pertinent articles were selected for inclusion in this review.

Transanal local excision

The TAE, first introduced by Parks in 1970, was a pioneering endoluminal approach for the resection of select rectal tumors.16 At its inception, TAE provided a less invasive alternative to traditional abdominal procedures, offering key benefits such as reduced recovery times, shorter length of stay (LOS) and lower complication rates for carefully selected patients.17, 18 Transanal local excision can be performed for selected early tumors that lack adverse prognostic factors, such as poor differentiation or lymphovascular invasion.2 The American Radium Society also supports the use of TAE for stage cT1N0 CRC, as defined by endorectal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging, provided specific patient selection criteria are met.19 The tumor should be smaller than 3 cm in size and well or moderately differentiated. It must be located in the low rectum and involve <30% of the rectal circumference. There should be no evidence of nodal involvement. Negative margins (greater than 3 mm) are required, and the excision must be feasible as a full-thickness procedure.

This technique is relatively straightforward and can be performed with ease. It does not require specialized equipment or an extensive learning curve; rather, anal retractors are used to facilitate access and visualization, making it a more cost-effective treatment option. One of the key advantages of TAE is its minimal impact, if any, on anorectal and urogenital function. However, one limitation is that visualization during the procedure can be suboptimal, potentially affecting the quality of the oncologic resection margins. This issue is further compounded by concerns about the high rates of tumor fragmentation and recurrence associated with TAE, which are likely linked to margin positivity – reported in over 10% of cases, even in the most experienced centers.20, 21 In a prospective Norwegian study, patients with T1 CRC treated with TAE had significantly higher 5-year local recurrence rates, reduced survival rates and lower disease-free survival (DFS) rates compared to those who underwent radical surgery.22

For T2 tumors, TAE may be considered in highly selected patients, particularly those who are not optimal candidates for more radical surgery due to comorbid conditions. However, the risk of locoregional recurrence is higher for T2 tumors, and neoadjuvant chemoradiation may be used to downstage the tumor before considering TAE.23, 24

Transanal endoscopic surgery: TEM, TAO, TAMIS

A decade later, several anorectal surgical techniques incorporating various instruments were developed. Transanal endoscopic surgery (TES) refers collectively to techniques – including TEM, TEO and TAMIS – that employ endoscopic platforms to excise rectal lesions.

Transanal endoscopic surgery platforms are currently employed for the treatment of endoscopically unresectable rectal adenomas, as well as for early-stage rectal cancers (T1 lesions).5, 7 They are also employed in cases where previous resections have been incomplete or performed piecemeal,25 and in selected cases of more advanced rectal cancers, typically in palliative or experimental settings. Beyond selected early-stage rectal cancers, TES has been successfully applied for the removal of various other types of tumors. It has also proven effective in treating benign conditions, including stricturoplasty, repair of complex urogenital fistulas and anastomotic leakage.26, 27, 28, 29, 30

The TEM platform, originally developed by Gerald Buess in 1982, was introduced as an advanced endoscopic tool for the local resection of rectal tumors.31 Transanal endoscopic microsurgery has emerged as an effective technique for the treatment of early-stage CRC and large sessile adenomas that cannot be removed locally or through conventional colonoscopic resection. The procedure employs a specialized rigid operating rectoscope, typically ranging from 12 to 20 cm in length, which is introduced transanally to provide enhanced visualization and precision during excision. This rectoscope features an optical system that offers a magnified, three-dimensional (3D) view of the surgical area, enabling precise full-thickness resections perpendicularly through the bowel wall into the perirectal fat, and is paired with endoscopic instruments. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is particularly advantageous for tumors located in the mid and upper rectum, which are difficult to access with conventional transanal excision techniques. The procedure maintains a stable pneumorectum using carbon dioxide insufflation, which enhances visibility and facilitates meticulous dissection and suturing.6, 32

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery has been shown to provide superior oncological outcomes compared to TAE for T1 rectal lesions. It is associated with lower rates of positive surgical margins and a reduced risk of local recurrence. Research by Christoforidis et al. demonstrated that TEM resulted in fewer positive margins (2% vs 16%, p = 0.017) and better DFS for tumors located ≥5 cm from the anal verge.33 Sgourakis et al. also found that TEM significantly lowered the chances of positive margins and local recurrences compared to TAE.34 These findings were further supported by a more recent meta-analysis, which showed that TEM achieved a higher rate of negative microscopic margins, a lower rate of specimen fragmentation and a reduced rate of lesion recurrence, with no significant difference in postoperative complications when compared to TAE.35 These findings collectively suggest that TEM offers oncological superiority over TAE.

A more cost-effective alternative to TEM was introduced a few years later: the TEO platform by Karl Storz (Tuttlingen, Germany). This innovative and more straightforward tool has gained widespread adoption. The TEO platform utilizes a rigid rectoscope (working length: 7.5–15 cm), curved laparoscopic operating instruments and a two-dimensional (2D) visualization system.36 The indications for TEO are comparable to those of TEM, although, like TEM, it presents challenges in excising lesions close to the anal verge. Transanal endoscopic operation benefits from lower costs associated with standard laparoscopic instruments, equipment and setup, making it more accessible to surgeons with prior laparoscopic experience.

Both TEM and TEO utilize rigid platforms, with the telescope fixed to a rigid steel proctoscope. Initially, these rigid platforms provided a stable surgical field but were limited by their lack of flexibility and the restricted field of view they offered. These limitations often resulted in prolonged setup times and difficulties in maneuvering instruments, especially in the distal rectum.37

Due to the significant costs associated with TEM and the extensive learning curve required to master the technique, an alternative transanal approach utilizing a single, disposable, multichannel port was introduced in 2010 by Atallah et al., now known as TAMIS.38 This advancement has contributed to the wider implementation of TES techniques, with a range of ports now available. The development of flexible platforms, in contrast to the rigid operating rectoscope, has resulted in reduced setup times and operative times,39 atraumatic retraction, and better compatibility with standard laparoscopic instruments and conventional CO2 insufflator, which are more accessible and cost-effective compared to the specialized, high-cost equipment required for TEM.38, 40 Additionally, TAMIS requires a less steep learning curve compared to TEM, as it utilizes familiar laparoscopic instruments and techniques, making it easier for surgeons with existing laparoscopic expertise to adopt the procedure.40 It also provides more flexibility in patient positioning; unlike TEM, which often necessitates specific positioning depending on the tumor’s location, TAMIS can be performed with the patient in a standard position.41 However, it poses challenges in suturing due its narrower operative field and more frequent instrument conflicts compared to TEM.37, 42 The longer channels of the TEM and TEO systems, on the other hand, facilitate intraluminal retraction of the rectum, allowing for better access and visibility during resection. In contrast, TAMIS often requires an assistant to maneuver the laparoscope, increasing complexity, and can be more difficult to access and removing rectal lesions behind a haustral valve.

While TAMIS is particularly effective for lesions in the mid to upper rectum, it has also been successfully used for lesions in the lower rectum.43 Furthermore, TAMIS has been associated with lower overall complication rates and fewer 30-day readmissions compared to rigid platforms like TEM, potentially leading to improved short-term postoperative outcomes for patients.44

Transanal endoscopic surgery offers several advantages over radical surgery, including lower morbidity and mortality rates, as well as faster recovery.2 While some studies comparing TEM to radical surgery for early-stage CRC have reported comparable outcomes in terms of local recurrence and overall survival (OS),45, 46 a more recent meta-analysis demonstrated a significantly increased risk of local recurrence following TEM. The analysis reported a risk ratio (RR) of 2.51 with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of 1.53–4.21, indicating a more than twofold increase in recurrence compared to radical surgery. This highlights the importance of careful patient selection to optimize treatment outcomes.47 The local recurrence rates for T1 early-stage rectal tumors treated with TES vary widely across studies, ranging from 2.4% to 26%.48 This variability may be attributed to the substantial risk of occult lymph node metastasis in T1 tumors, particularly when unfavorable histopathological features are present. For instance, a study by O’Neill et al. reported a 3-year local recurrence rate of 2.4% for T1 rectal tumors treated with TEM,49 while Stipa et al. found a higher rate of 11.6%.50 Additionally, a meta-analysis by Dekkers et al. reported an overall pooled recurrence incidence of 9.1% for T1 CRC treated with local resection techniques, including TEM.51 These variations highlight the importance of patient selection and the need for careful postoperative surveillance to detect and manage recurrences early.

T1 tumors larger than 4 cm, involving more than 30% of the bowel circumference, and exhibiting high-risk histological features are associated with an increased risk of local recurrence following local excision. In these cases, the TES approach should be avoided.52, 53, 54, 55, 56 For T2 or more advanced lesions, TME, with or without neoadjuvant therapy, is the standard treatment.

Importantly, studies have not shown any long-term complications related to continence or anorectal function resulting from the transanal placement of ports in TES, further supporting its safety profile in both oncologic and benign applications.57, 58, 59

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) is a minimally invasive approach that accesses the abdominal cavity via natural orifices. Initially performed on humans in 2008, NOTES introduced the potential for “scarless surgery”.60 This technique involves the controlled puncture of an organ (e.g., stomach, rectum, vagina, etc.) with an endoscope to gain access to the abdominal cavity.61, 62

This technique has been explored for a variety of procedures, including cholecystectomy, appendectomy and peritoneoscopy. Various access routes have been tested, such as transgastric, transvaginal, transvesical, and transcolonic approaches.61, 63 The primary advantages of NOTES include reduced postoperative pain, faster recovery, fewer wound infections, and improved cosmetic outcomes due to the absence of external scars.63, 64

Despite its promising potential, NOTES remains an experimental technique with several challenges. These include the risk of infection, the need for reliable closure of viscerotomy sites and the development of specialized instruments tailored to the procedure.62, 63 Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) have highlighted critical goals and obstacles that must be addressed before NOTES can be widely adopted in clinical practice.62

While NOTES represents an exciting advancement in minimally invasive surgery, further research and technological development are essential to ensure its safety and efficacy before it becomes standard practice in clinical settings.

Transanal natural orifice specimen extraction

Transanal natural orifice specimen extraction (ta-NOSE) combines the benefits of laparoscopic techniques with the natural orifice approach for specimen removal. The method enables for the complete resection of the colon or rectum laparoscopically, followed by the extraction of the resected specimen via a natural orifice, usually the anus, without the need for a traditional mini-laparotomy. This eliminates some of the risks associated with conventional open surgery, such as larger incisions and subsequent complications like infections, hernias, postoperative pain, and prolonged recovery. At first, transvaginal and ta-NOSE were used for benign diseases,65, 66, 67, 68, 69 but over time, both techniques were explored for CRC treatment.70, 71, 72, 73

Cheung et al. conducted the first trial of laparoscopic colectomy with ta-NOSE in 2009.70 The study involved 10 patients with left-sided CRC (4 cm or less in size) who underwent laparoscopic resection followed by transanal specimen retrieval using the TEO device setup. The authors showed that the technique is feasible for carefully selected patients with left-sided CRC.

The largest cohort study on NOSE for CRC was conducted by Franklin et al., who usually employed transanal specimen extraction during laparoscopic anterior resection (LAR).73 In their prospective study involving 179 patients, they reported successfully performing laparoscopic TME, followed by transanal specimen retrieval using specialized instruments. The study found a low overall complication rate (5.0%), with an anastomotic leak rate of 1.7% and rectal stenosis occurring in 2.0% of cases.

Additionally, several studies have shown that ta-NOSE is both feasible and safe. For instance, Ng et al. demonstrated that ta-NOSE, when combined with LAR for sigmoid and CRC, resulted in lower operative blood loss and shorter LOS compared to conventional LAR.74 Similarly, Xu et al. found that laparoscopic-assisted NOSE colectomy for left-sided CRC resulted in lower postoperative pain and faster recovery of gastrointestinal function compared to conventional laparoscopic colectomy.75 The technique consists of standard laparoscopic dissection and vascular control, followed by specimen extraction through the rectum using specialized instruments designed to protect the rectal and anal tissues.

Studies have shown that, in addition to benefits such as reduced postoperative pain, shorter LOS, and improved cosmetic outcomes, ta-NOSE maintains oncological safety by ensuring adequate lymph node retrieval and clear resection margins.76, 77

Transanal total mesorectal excision

For patients with rectal cancer who are not eligible for local surgery, transabdominal resection is recommended. Total mesorectal excision is a cornerstone in the surgical treatment of CRC,78 aiming to achieve complete removal of the mesorectum, which contains lymph nodes and potential sites of tumor spread, while preserving key anatomical structures.79 In 1982, Prof. Richard Heald revolutionized CRC surgery by identifying that cancer primarily spreads through lymphatic and venous pathways rather than distally along the rectum. He emphasized the importance of the “holy plane”, an avascular space between the mesorectum and its surrounding structures, as the key to precise dissection.80 Heald’s concept demonstrated that incomplete resection within this “danger zone” could explain high local recurrence rates, making proper TME within this plane a critical factor in reducing recurrence and improving outcomes. Initially performed as an open procedure, TME quickly became the standard of care in rectal cancer treatment.81, 82

The introduction of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (LaTME) brought the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, such as reduced postoperative pain and shorter LOS. However, concerns emerged regarding its oncological safety. The COLOR II trial83 demonstrated that LaTME offered similar oncological outcomes to open surgery while enhancing recovery. Despite these benefits, LaTME presented significant challenges, including a 17% conversion rate to open surgery, particularly in anatomically difficult cases such as patients with a narrow pelvis.83, 84 To address these limitations, robotic TME (RoTME) was introduced, offering improved dexterity, enhanced 3D visualization and better ergonomics. While studies like the ROLARR trial showed similar oncological outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic approaches, robotic surgery has been linked to increased costs and longer procedure times.85

To tackle the challenges of achieving optimal distal mesorectal dissection, taTME was developed. By initiating dissection from the anus, surgeons could achieve better visualization and precision when accessing the distal rectum. In the late 2000s, experimental work by Mark Whiteford, Patricia Sylla, et al. demonstrated the feasibility of NOTES transanal rectosigmoid resection in swine and cadaveric models, laying the groundwork for clinical application.86, 87 The first clinical description of taTME was published in 2010, marking a significant advancement in minimally invasive colorectal surgery.14 Transanal TME employs a “bottom-up” approach, combining the principles of precise oncological resection, minimally invasive techniques and enhanced visualization.88 This comprehensive technique integrates key advancements from the last 3 decades of rectal cancer surgery.

Transanal TME offers several potential advantages for mid and low rectal cancers, particularly in anatomically challenging cases such as those involving obesity, a narrow pelvis or previous pelvic irradiation. By combining transanal and abdominal approaches, the technique enhances visualization, facilitates precision in dissecting the mesorectal plane and ensures improved specimen quality.89 Early studies reported promising results, with low occurrences of positive circumferential resection margins and improved oncological radicality.90 Registry data have further informed the discussion around taTME. The International taTME registry compiled data from 720 cases and reported high rates of intact TME specimens (85%), low positive margin rates (2.7%) and low rates of anastomotic leakage (5.5%) when performed by experienced surgeons.91 However, concerns over the complexity of the technique and the need for structured training programs have tempered its adoption. Following an initial wave of enthusiasm supported by promising outcomes from expert centers,92 data from national studies in Norway93 and the Netherlands94 raised concerns about the procedure’s safety. These studies revealed significantly higher local recurrence rates for taTME compared to the laparoscopic approach, prompting questions about its risks. The Norwegian moratorium, released in 2019, reported an initial recurrence rate of 9.5% following a median follow-up period of 11 months.95 A nationwide audit in Norway raised concerns about the long-term oncological results of taTME, reporting a local recurrence rate of 11.6% after 2 years in 157 patients who had undergone the procedure. This contrasted with a recurrence rate of 2.4% in a cohort from the Norwegian CRC Registry.93

To further support the oncologic safety of taTME, Roodbeen et al. published findings from the International taTME Registry.96 Among 2,803 patients undergoing primary taTME, the 2-year local recurrence rate was 4.8%. The 2-year DFS and OS rates were 77% and 92%, respectively. Additionally, taTME has shown functional outcomes and quality of life similar to those achieved with LaTME.97, 98 Despite these promising findings, the broad implementation of taTME has been hindered by a demanding learning curve99, 100 and concerns over oncological and functional outcomes.101, 102, 103, 104 Studies suggest that a center must perform at least 20–30 cases to achieve proficiency, underscoring the need for structured training programs such as cadaveric workshops and proctorships.105 It is widely agreed that taTME should only be performed by well-trained colorectal surgeons in high-volume centers to minimize complications and ensure oncological adequacy.90

In summary, taTME marks a major progress in rectal cancer surgery, providing enhanced visualization and access to the distal rectum. While early results are promising, caution must guide its adoption, with emphasis on rigorous training, adherence to oncological principles and ongoing evaluation of outcomes. Future studies and registry data will continue to refine its role within the spectrum of surgical options for rectal cancer.

Transanal transection and single-stapled anastomosis

The TTSS approach represents the latest and most promising advancement in transanal techniques for the treatment of low rectal cancers. The TTSS technique seeks to integrate the strengths of 2 well-established surgical strategies. From traditional TME, it draws upon the long-established dissection technique, honed over generations, and has been proven to be both safe and effective in both conventional open surgeries and minimally invasive approaches. From taTME, it incorporates the concept of transanal transection (TT) and the single-stapled (SS) anastomosis, though with significant technical variations.106

The technique, introduced by Spinelli et al. in 2019, was initially tested on a small cohort of patients undergoing low rectal surgery. The complications consisted of 1 grade IIIa and 3 grade I events, as defined by the Clavien–Dindo classification. The proof-of-concept study demonstrated that TTSS is both safe and feasible in all patients.107

In contrast to taTME, the TTSS technique involves placing the transanal purse string only after the full peri-mesorectal dissection is completed, performed from above through either a conventional or less invasive abdominal approach. After fully mobilizing the lower rectum and mesorectum from the pelvic floor muscles, a full-thickness, circumferential rectotomy is performed using electrocautery.

In TTSS, the rectal cuff below the transection site is fully detached from the pelvic floor before sectioning. This enables the surgeon to place the lower purse string for the anastomosis without the need for further complex or risky maneuvers to mobilize it. Following the transection, a single-stapled anastomosis is created to connect the remaining rectal stump with the proximal bowel (colon or ileum). The single-stapled method eliminates some of the complications associated with double-stapled anastomosis, such as uneven cuff lengths and potential weak points.

Clinical studies have demonstrated that TTSS is linked to reduced rates of anastomotic leakage (AL) and improved functional outcomes compared to double-stapled (DS) techniques.106, 108

In the study by Spinelli et al.,106 both SS techniques – taTME and TTSS – resulted in considerably lower AL rates than the DS technique. The reintervention rate was also reduced in the TTSS group compared to DS, with a significant difference observed (2% vs 12%). These findings suggest that the TTSS approach offers greater safety regarding AL, with fewer patients needing re-intervention for leaks. While overall 30-day complication rates were similar across all 3 techniques (DS, taTME and TTSS), the TTSS group had significantly fewer complications at 90 days compared to the DS group. Additionally, the operative time was notably longer in the taTME group when compared to both TTSS and DS.

Similarly, Harji et al. noted a considerable decrease in AL rates with TTSS in CRC surgery compared to the DS technique.109 Interestingly, no significant difference was found in the low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) scores between patients who underwent TTSS and those who received the DS technique (p = 0.228).

The taTME technique is recognized for being linked to longer operative times and higher procedural costs, primarily due to the requirement for specialized transanal equipment. These factors contribute to taTME being a more expensive surgical option overall. On the other hand, the TTSS is more cost-efficient, utilizing only a single circular stapler (of any available type) in conjunction with basic, low-cost instruments. As a result, TTSS represents a more affordable alternative to taTME, particularly in resource-limited settings, while still preserving the benefits of transanal surgery.

Although the precise number of cases needed to master TTSS remains unclear, initial results suggest that TTSS may be less complex than taTME, potentially requiring fewer cases to achieve comparable outcomes.107 However, larger, comparative, and multicenter studies are necessary to confirm and further support these results.

Limitations

First, the inclusion of heterogeneous studies, differing in research scope, study design, participant demographics, and contexts, introduces variability that may affect the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, no date limit was applied, and studies published up until January 2025 were included, which may result in the inclusion of studies with varying levels of methodological rigor and relevance to current practices. Although the study aimed to cover a broad range of research, the inclusion criteria were limited to original studies written in English, which could exclude relevant data published in other languages.

Conclusions

Over the past few decades, transanal surgical techniques for rectal cancer have evolved significantly. The progression from TAE to more advanced methods, such as TEM, TEO, and later TAMIS, has resulted in notable advancements in treatment options for patients with early-stage rectal cancer. These techniques offer greater precision, less invasive surgery and improved functional outcomes. More recent approaches, such as taTME and TTSS, are particularly effective for low rectal tumors that are not suitable for local excision. These newer methods enhance precision in mesorectal plane dissection, ensure better specimen quality and show promising oncological results.

In conclusion, appropriate patient selection is crucial for achieving optimal outcomes. Surgeons must be well-informed about the various available treatment options. Furthermore, as these techniques continue to evolve, further research and larger studies are needed to refine patient selection and validate long-term outcomes.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technology

Not applicable.