Abstract

Background. Healthcare systems can present unique challenges for individuals in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community, often making it difficult for them to access suitable and respectful care.

Objectives. The aim of this study was to perform a transcultural adaptations and to evaluate psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Development of Clinical Skills Scale (LGBT-DOCSS-ES). This adaptation is intended for application within Spanish-speaking healthcare settings.

Materials and methods. The LGBT-DOCSS was translated and adapted from the original English version into Spanish using a standardized process, including forward translation, back-translation, and expert panel review. Psychometric properties were tested on a sample of 270 participants from Spain. Internal consistency was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), Cronbach’s alpha, the discriminative power index, and McDonald’s omega (ω).

Results. The study included 270 participants, with 58.9% being female and 38.9% male. Of the respondents, 52.2% identified as heterosexual, 32.6% as homosexual and 13% as bisexual. The internal consistency of the Spanish version and its domains was good with an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.746. The alpha ranges for each subscale domains were between 0.769 and 0.822. The McDonald’s ω coefficient was 0.808.

Conclusions. The Spanish version of the LGBT-DOCSS-ES has good properties of factorial validity. This tool is a valuable resource for assessing cultural competence and clinical skills among healthcare providers in Spanish-speaking settings.

Key words: interdisciplinary, international, self-assessment, LGBT competence

Background

In 2023, 14% of the Spanish population identified themselves as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, or other (LGBT+), making Spain the country with the second-highest percentage of self-identified LGBT+ individuals globally, just behind Brazil at 15%.1 Despite this, LGBT+ individuals frequently experience significant disparities in healthcare, primarily due to stigma and discrimination.2 Stigma within the healthcare system continues to be a significant barrier, preventing LGBT+ individuals from accessing the care they require.3, 4

Spain consistently ranks among the leading European countries in LGBT+ equality, as noted in the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) 2023 report for Europe. The country’s progressive legislation, including the prohibition of conversion therapy practices and advancements in transgender healthcare, reinforces its position as a regional leader. Spain’s commitment to equality is also reflected in its participation in European initiatives to counter anti-LGBT+ measures in other nations.5

Healthcare professionals often lack sufficient training on LGBT+ specific health issues, which can contribute to the perpetuation of stereotypes and discriminatory practices.6 Existing literature highlights the importance of LGBT+-specific assessment tools in healthcare to improve cultural competence among healthcare providers. Research shows that culturally competent care enhances trust, satisfaction and health outcomes for LGBT+ individuals.7, 8 Such tools are crucial in providing inclusive and non-discriminatory care, addressing health disparities within LGBT+ populations and ensuring compliance with international guidelines on equality in healthcare services.9 This deficiency results in negative experiences for LGBT+ patients, fostering mistrust in the healthcare system and its professionals and ultimately leading some individuals to avoid seeking care altogether.10, 11 Such barriers can further exacerbate the physical and mental health challenges faced by LGBT+ populations.12 Studies such as Lattanner et al. indicate that structural stigma related to LGBT+ health issues has an effect size comparable to other well-established risk factors for poor health, including income inequality, racial or cultural segregation, and socioeconomic status.13 The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that healthcare services should be accessible to all and free from discrimination. The adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, with its commitment to “leave no one behind”, further underscores the need to address and improve the health and wellbeing of LGBT+ individuals.14

Research has demonstrated that healthcare professionals with greater cultural competence and specific clinical skills are crucial for providing inclusive and effective care to the LGBT+ community.15, 16, 17, 18 Increasing healthcare professionals’ competencies significantly enhances patient satisfaction and bolsters trust in the healthcare system.6, 19 Similarly, LGBT+ cultural competency training programs have improved healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors, increasing satisfaction and better health outcomes for LGBT+ patients.8 These programs typically focus on increasing awareness of LGBT health disparities, addressing unconscious biases and developing practical communication skills to ensure more inclusive and patient-centered care. Continuous education and training in LGBT+ cultural competency are essential for improving healthcare professionals’ attitudes and practices, promoting inclusive care, reducing health disparities and building trust within the LGBT+ community.6, 20, 21 It is therefore necessary to implement and promote research on the health of LGBT+ individuals to mitigate health inequities, provide inclusive healthcare services and improve the health of this population.22

A cross-cultural study comparing 7 European countries, including Spain, highlighted significant training needs related to LGBT+ health issues, particularly in areas such as understanding sexual orientation, gender identity, and discrimination against LGBT+ individuals. These training needs were especially pronounced among Spanish health professionals, underscoring the critical role of targeted education in addressing health disparities.23 The concept of LGBT cultural competence refers to the ability of healthcare professionals to provide respectful, informed, and inclusive care to LGBT patients. It encompasses 3 key domains: Knowledge (understanding the unique health needs and disparities faced by LGBT individuals), Attitudes (awareness of biases and commitment to non-discriminatory care) and Clinical Preparedness (confidence in addressing LGBT health concerns in practice).8, 24, 25 Various frameworks have been proposed to measure LGBT cultural competence, including self-assessment tools, patient-reported experiences and structured evaluations of provider training.8, 26, 27 The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Development of Clinical Skills Scale (LGBT-DOCSS) is one of the few validated instruments designed specifically to assess these competencies in healthcare settings, focusing on the readiness of professionals to engage with LGBT patients in a culturally sensitive manner.25 It has been widely used to evaluate the competencies of diverse healthcare professionals, including physicians, nurses, medical students, and allied health practitioners, making it a versatile tool for assessing LGBT-inclusive clinical skills across different medical and educational contexts.28, 29, 30 Unlike other instruments, such as the Sexual Orientation Counselor Competency Scale (SOCCSS),26 which primarily assesses counseling-related skills, or the Gay Affirmative Practice Scale (GAP),27 which focuses on affirmative attitudes rather than Clinical Preparedness, the LGBT-DOCSS is specifically tailored for healthcare professionals. Its structured 3-domain model allows for a more targeted assessment of both attitudinal and practical dimensions of LGBT patient care.25 This specificity, along with its strong psychometric properties, was the key reason for selecting LGBT-DOCSS as the basis for this study.

As no comparable tool is currently available in Spain, this study aimed to perform a cross-cultural adaptation and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the LGBT-DOCSS (LGBT-DOCSS-ES).

Materials and methods

Adaptation process

The linguistic and cross-cultural adaptation of the LGBT-DOCSS followed the standardized 6-step approach proposed by Beaton et al., ensuring methodological rigor in its adaptation to Spanish.31 The adaptation process involved 6 stages: 1) initial translation, 2) synthesis of translations, 3) back translation, 4) expert committee review, 5) pre-testing of the translated version, and 6) final evaluation.

The initial translation of the LGBT-DOCSS-ES into Spanish was conducted independently by 2 bilingual translators with expertise in healthcare terminology. Following this, these translations were synthesized to ensure consistency and conceptual clarity. This Spanish version was back-translated into English by bilingual translators blind to the original English content. A native English speaker reviewed the back-translated version to check for discrepancies.

Additionally, an expert committee, consisting of native speakers with clinical backgrounds, compared both the original and back-translated versions of the LGBT-DOCSS. Through consensus, the committee established the final Spanish version, ensuring that it preserved the conceptual intent of the original tool. The expert committee included a diverse group of professionals: a public health specialist, a psychologist, a medical doctor, a nurse, and a paramedic. Each committee member had at least 5 years of experience in their respective fields and specific familiarity with the LGBT community. This collective expertise ensured that the adapted version was culturally and clinically relevant. Specific linguistic adjustments were made to enhance accessibility for Spanish-speaking healthcare professionals.

In the final phase, cognitive interviews were conducted with a convenience sample of 35 healthcare professionals to assess the translated version’s clarity, cultural applicability and linguistic accuracy. Participants were selected based on their current employment in healthcare and ability to provide feedback on language and cultural relevance. No significant issues were identified, but based on minor observations, small adjustments were made to enhance readability and relevance. These adjustments ensured that the scale is both linguistically accessible and conceptually appropriate; however, the primary aim of this study was to validate the psychometric properties of the Spanish version for use in Spanish-speaking healthcare settings.

Procedure

A cross-sectional study was conducted between May 2024 and December 2024, enrolling 270 participants through convenience sampling via social media platforms such as Instagram and a dedicated Facebook group for healthcare professionals. The convenience sampling approach was chosen to maximize accessibility and participation among healthcare professionals actively engaged on social media platforms. This method enabled the recruitment of a diverse sample representing various healthcare professions, including nurses, medical doctors and health sciences students. For the calculation, the recommendations for this type of study were considered, which indicated recruiting between 5 to 10 participants per item, with a minimum of 180 (18 items), according to Argimon-Pallás.32

All participants who met the inclusion criteria, i.e., being medical and/or healthcare students or professionals and voluntarily agreed to participate, completed an anonymous survey after receiving comprehensive study information and giving their informed consent. The inclusion criteria ensured that participants were either medical or healthcare students or active professionals, allowing us to capture perspectives from individuals at different stages in their careers.

The data were collected, and sample access was controlled via the Webankieta platform, which utilized IP filtering for enhanced security. This filtering mechanism ensured that if multiple questionnaires were submitted from the same IP address, only the first completed response was considered, minimizing the risk of duplicate entries. No such instances were detected during data collection.

A convenience sampling approach was employed due to its feasibility and accessibility in reaching healthcare professionals actively engaged on social media platforms. This method allowed for rapid recruitment of a diverse group of participants from various healthcare fields, including nurses, medical doctors and health sciences students. While convenience sampling offers practical advantages, such as ease of implementation and cost-effectiveness, it also introduces limitations regarding the representativeness of the sample. Participants who voluntarily responded to the survey may have had a greater pre-existing interest in LGBT+ healthcare issues, which could introduce a selection bias. Additionally, the sample may not fully reflect the broader population of Spanish-speaking healthcare professionals, particularly those who are less active on digital platforms. However, efforts were made to include individuals from diverse geographic locations, professional backgrounds and demographic groups, as reflected in Table 1. The potential impact of these limitations on the generalizability of the findings is further addressed in the Limitations section.

Psychometric evaluation

To validate the psychometric properties of the LGBT-DOCSS-ES, internal consistency and factorial validity were assessed. The factorial structure was examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), employing the Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimation method, which is appropriate for ordinal data. Model fit was evaluated using the Hu–Bentler 2-index strategy, incorporating standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) indices. The criteria for acceptable model fit were set as SRMR < 0.09, along with at least one of the following: CFI > 0.96, TLI > 0.96 or RMSEA < 0.06. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) to evaluate the reliability of the total scale and its factors. In addition, the discriminative power index was employed to determine the contribution of individual items to the internal consistency of each factors. The interpretation of α values followed conventional thresholds: α ≥ 0.9 was considered excellent, 0.8 ≤ α < 0.9 good, 0.7 ≤ α < 0.8 acceptable, 0.6 ≤ α < 0.7 questionable, 0.5 ≤ α < 0.6 poor, and α < 0.5 unacceptable. R v. 4.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)was used along with RStudio33 GUI and psy,34 lavaan,35 psych,36 and diagram packages.37

Measures

The survey consisted of 2 sections: 1. Demographic questionnaire: This section collected information on age, gender identity, sexual orientation, place of residence, relationship status, medical occupation, and prior participation in LGBT-related training. The phrasing of demographic questions regarding gender identity and sexual orientation followed international recommendations to ensure inclusivity and accuracy. Gender identity was assessed with the options: cisgender female, cisgender male, nonbinary, transgender man, and transgender woman. Sexual orientation was measured using the categories: heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, other, and “I prefer not to respond”.

LGBT-DOCSS – The LGBT-DOCSS, which assessed healthcare practitioners’ clinical skills in LGBT patient care, was developed and validated by Bidell in the USA.25 It consists of 18 items and is categorized into three factors: Clinical Preparedness, Attitudinal Awareness and Basic Knowledge. Respondents use a 7-point Likert scale, rating their agreement with each statement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Eight of the items are scored inversely to ensure that higher scores consistently reflect more affirmative attitudes, greater knowledge and a higher willingness to engage with LGBT patients. The total LGBT-DOCSS score is derived by averaging the scores of all items. Additionally, factors scores are calculated by averaging the items related to Basic Knowledge, Attitudinal Awareness and Clinical Preparedness. Higher points on the factors and overall indicate better Clinical Preparedness, more positive attitudes and greater knowledge of LGBT healthcare.

Ethical consideration

The research adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Bioethics Committee at Wroclaw Medical University in Poland (approval No. KB 976/2022) as well as from the University of Valencia (approval No. 2024-ENFPOD-3314668). This study is a component of the Health Exclusion Research in Europe (HERE) initiative. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines to ensure the reliability and clarity of the observational study reporting.

Results

Participants

The study included 270 participants, with 58.89% identifying as female, 38.89% as male and 2.22% as nonbinary, transgender men, or transgender women. The median age of participants was 34 years (range: 18–67). Regarding residence, 32.96% lived in cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants, 20.00% in cities between 100,000 and 500,000, 19.26% in cities between 20,000 and 100,000, 5.19% in cities with up to 20,000 inhabitants, and 22.59% in villages. In terms of sexual orientation, 52.22% identified as heterosexual, 32.59% as homosexual and 12.96% as bisexual. Most participants were in a formal relationship (39.63%), including 28.15% who were married and approx. 11% who were in other legally recognized unions, such as registered partnerships or civil unions. Additionally, 23.33% of participants were single. Nurses and their specialties, including midwives, represented the largest professional group (65.95%). In the past 5 years, 39.63% of participants reported attending courses on LGBT patient issues, while 60.37% stated that they had not participated in such training. Sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

LGBT-DOCSS-ES results

The mean total score was 5.19 (standard deviation (SD) = 0.72), with a range from 3 to 7. The mean score for Clinical Preparedness was 4.16 (SD = 1.36), with scores ranging from 1.29 to 7. The Attitudinal Awareness factors showed the highest mean score of 6.77 (SD = 0.59), with a range from 1.43 to 7. The Basic Knowledge factors had a mean score of 4.23 (SD = 1.58), ranging from 1 to 7. Detailed descriptive statistics for each factors and the total score are provided in Table 2.

Analysis of individual questionnaire items

Table 3 illustrates the results for individual questionnaire items, emphasizing a notable ceiling effect observed in items 3, 5, 7, 9, 12, 17, and 18.

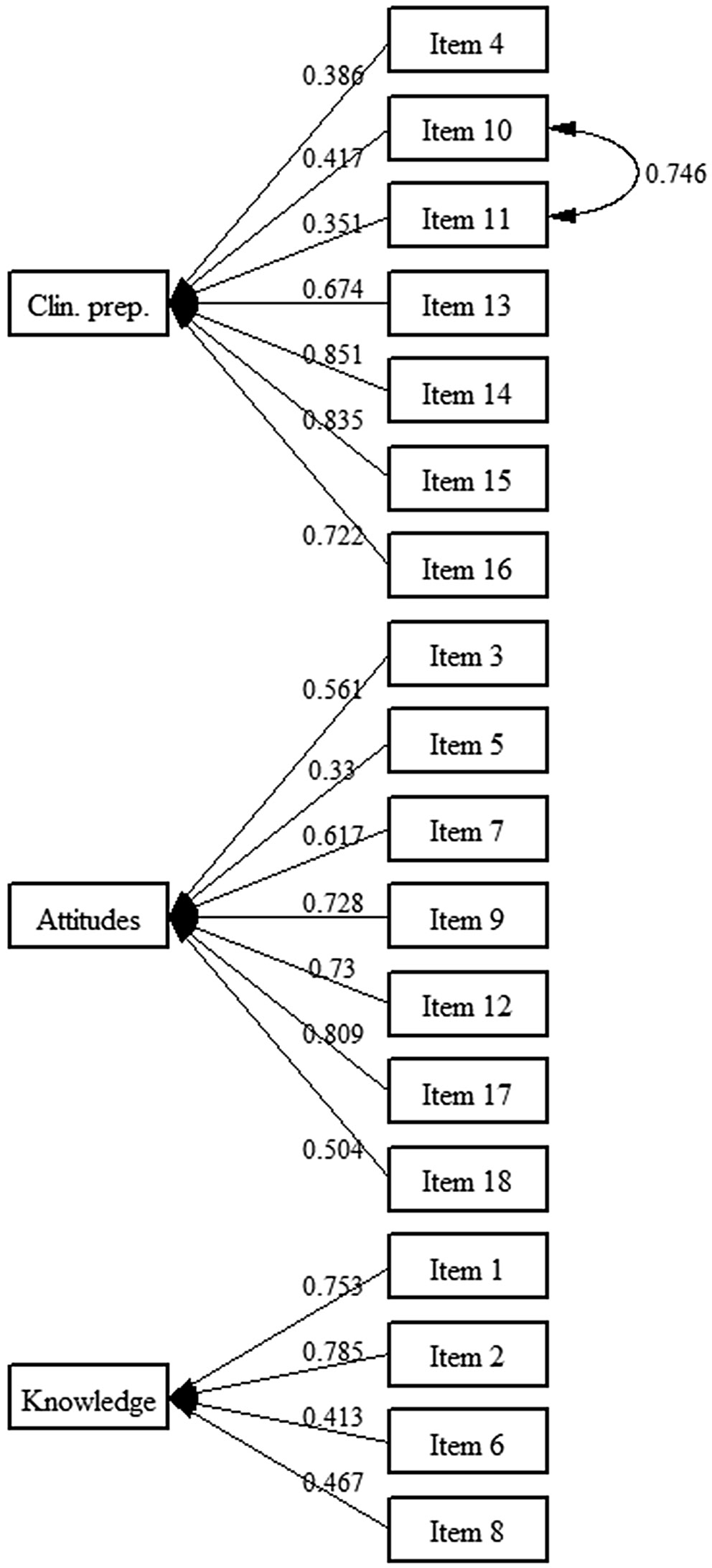

Confirmatory factor analysis

As the LGBT-DOCSS-ES questionnaire items are measured on an ordinal scale, the DWLS approach was utilized for CFA. The initial 3-factor model exhibited suboptimal fit indices. To improve model fit, a correlation between items 10 and 11 was incorporated, following recommendations from modification indices. This adjustment resulted in improved fit indices, meeting recommended thresholds (SRMR < 0.09, RMSEA < 0.06). The added correlations linked items within the same factor, ensuring consistency in measurement. This adjustment preserved the original factor structure of the LGBT-DOCSS. Detailed results are shown in Table 4.

Internal consistency analysis of the LGBT-DOCSS-ES

The factor loadings for individual items ranged from 0.33 to 0.851, all of which were statistically significant (p < 0.05). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the 3 factors demonstrated acceptable internal consistency: Clinical Preparedness (α = 0.822), Attitudinal Awareness (α = 0.781) and Basic Knowledge (α = 0.769). The overall reliability of the scale was satisfactory, with a total Cronbach’s alpha of 0.746. McDonald’s ω index (ω = 0.808) further confirmed the strong internal consistency of the scale. Detailed results for factor loadings and internal consistency are presented in Table 5.

An additional reliability analysis examined whether removing individual items would significantly impact internal consistency. While minor increases in Cronbach’s alpha were observed (e.g., excluding Item 4 slightly raised α for Clinical Preparedness to 0.830), these changes were negligible and did not justify item deletion. Full results of this analysis are presented in Table 6. The path diagram for the CFA of the LGBT-DOCSS-ES is illustrated in Figure 1. The final version of the LGBT-DOCSS-ES is presented in Table 7.

Discussion

The results suggest that the LGBT-DOCSS-ES demonstrates good psychometric properties, indicating that it is a reliable tool for assessing clinical skills in Spanish-speaking healthcare professionals. This finding supports the scale’s applicability in evaluating LGBT cultural competence in diverse linguistic and healthcare contexts. Only minor adjustments to certain expressions were made to ensure cultural appropriateness, but the primary focus remained on evaluating the scale’s psychometric properties. Findings from this study align with previous research on the LGBT-DOCSS, supporting its cross-cultural applicability.

The internal consistency of the Spanish version of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Development of Clinical Skills Scale (LGBT-DOCSS-ES) aligns with findings from other adaptations of the scale, including the Polish (LGBT-DOCSS-PL) and Japanese (LGBT-DOCSS-JP) versions, which have demonstrated stable psychometric properties across different cultural contexts.25, 38, 39 While some variations exist between language adaptations, previous research suggests that the scale maintains its reliability, supporting its use in evaluating LGBT clinical skills among healthcare professionals.25 These results indicate that the Spanish version maintains the scale’s reliability, confirming its utility for assessing LGBT clinical skills.

In each version, the 2 original factors, such as Clinical Preparedness, Attitudinal Awareness and Basic Knowledge, consistently demonstrated strong internal reliability across different language adaptations.38 The findings from the LGBT-DOCSS-ES align closely with those reported for the Polish version, further supporting the scale’s stability in diverse healthcare settings.38 In contrast, the original validation by Bidell reported slightly higher reliability scores across all factors.25 Notably, the Japanese adaptation introduced an additional factor related to Clinical Training, which was not observed in the Polish or Spanish versions.39 This suggests that, in certain cultural contexts, formalized clinical training may play a more distinct role in shaping LGBT competency, whereas in other regions, the original 3-factor structure remains sufficient.

This difference in factor structure could be attributed to variations in healthcare education systems and the emphasis placed on LGBT-related training. In Japan, where formalized LGBT medical education remains limited, a separate “Clinical Training” factor may reflect the necessity of structured instruction in LGBT patient care. Conversely, in Spain and Poland, where LGBT topics are increasingly integrated into broader medical education, Clinical Preparedness, Attitudinal Awareness and Basic Knowledge appear to be conceptualized as more interrelated dimensions. This highlights the importance of contextualizing LGBT competency assessment within specific cultural and educational frameworks. Cultural differences may influence the factor structure of the LGBT-DOCSS-ES by shaping perceptions of competencies like Clinical Preparedness, Attitudinal Awareness and Basic Knowledge within different healthcare contexts. For instance, societal attitudes towards LGBT individuals and varying healthcare training standards across cultures can lead to different emphases on specific items within these factors. These variations suggest that while core competencies remain consistent, cultural context may shift the relative importance or interpretation of certain items. Norms and values can significantly impact how respondents interpret survey items, influencing the overall findings.40, 41

This factorial structure of the instrument reflects the content that some authors suggest should be included in a competency training program aimed at healthcare professionals to improve care for individuals in the LGBT community.42 The linguistic adaptation process in all versions involved minor modifications to ensure cultural relevance. In the Spanish version, expressions were slightly adjusted to ensure they resonated with local healthcare professionals, a practice similarly observed in the Polish and Japanese adaptations. Notably, while all adaptations followed a standardized translation process, differences in healthcare terminology and cultural attitudes towards LGBT healthcare led to nuanced linguistic adjustments. The Polish and Japanese versions required additional refinements to align with their respective medical and social frameworks, illustrating the flexibility needed when implementing competency assessments across diverse populations. Significantly, these modifications did not impact the core structure or reliability of the scale.

The LGBT-DOCSS-ES provides a reliable and valid tool for assessing Clinical Preparedness, Attitudinal Awareness and Basic Knowledge of healthcare professionals regarding LGBT patient care. Its application can support scientific research exploring healthcare disparities, educational programs aimed at improving LGBT-related competencies among medical students and practitioners, and workforce training initiatives designed to enhance inclusive healthcare practices. In Spain, this instrument can be particularly valuable for identifying knowledge gaps among healthcare professionals, informing curriculum development in medical and nursing schools, and guiding policy recommendations to improve LGBT healthcare inclusion. Future studies can further explore its use in longitudinal assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions and training programs focused on LGBT competency development.

Limitations

While the sample size was adequate to address the primary objectives, expanding the participant pool could provide deeper insights, especially for subgroups such as non-binary individuals. Additionally, relying exclusively on online data collection may have excluded individuals without stable internet access, potentially reducing the inclusivity of the sample. While convenience sampling effectively recruited a diverse group of healthcare professionals, it may have introduced selection bias, as individuals with a preexisting interest in LGBT+ healthcare were more likely to participate. This could have influenced the overall results by overrepresenting respondents with greater knowledge or more positive Attitudinal Awareness toward LGBT+ patients. Furthermore, the reliance on digital recruitment strategies may have limited participation from healthcare professionals who are less engaged with online platforms, affecting the representativeness of the sample. Finally, relying on self-reported data may have introduced response bias, as participants might have given socially desirable answers, especially considering the sensitive nature of LGBT healthcare topics. Future research should consider employing stratified or random sampling methods to enhance the generalizability of findings to the broader population of Spanish-speaking healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

The findings of this study on the translation and cultural adaptation of the Spanish version of the LGBT-DOCSS-ES indicate that the tool demonstrates acceptable internal consistency and validity. The LGBT-DOCSS-ES holds potential value for research. Compared to the original instrument, the psychometric properties and outcomes of the transcultural adaptation were consistent with those of the original English-language validated version of the LGBT-DOCSS.

Data availability statement

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are openly available in [repository name] at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14741597.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.