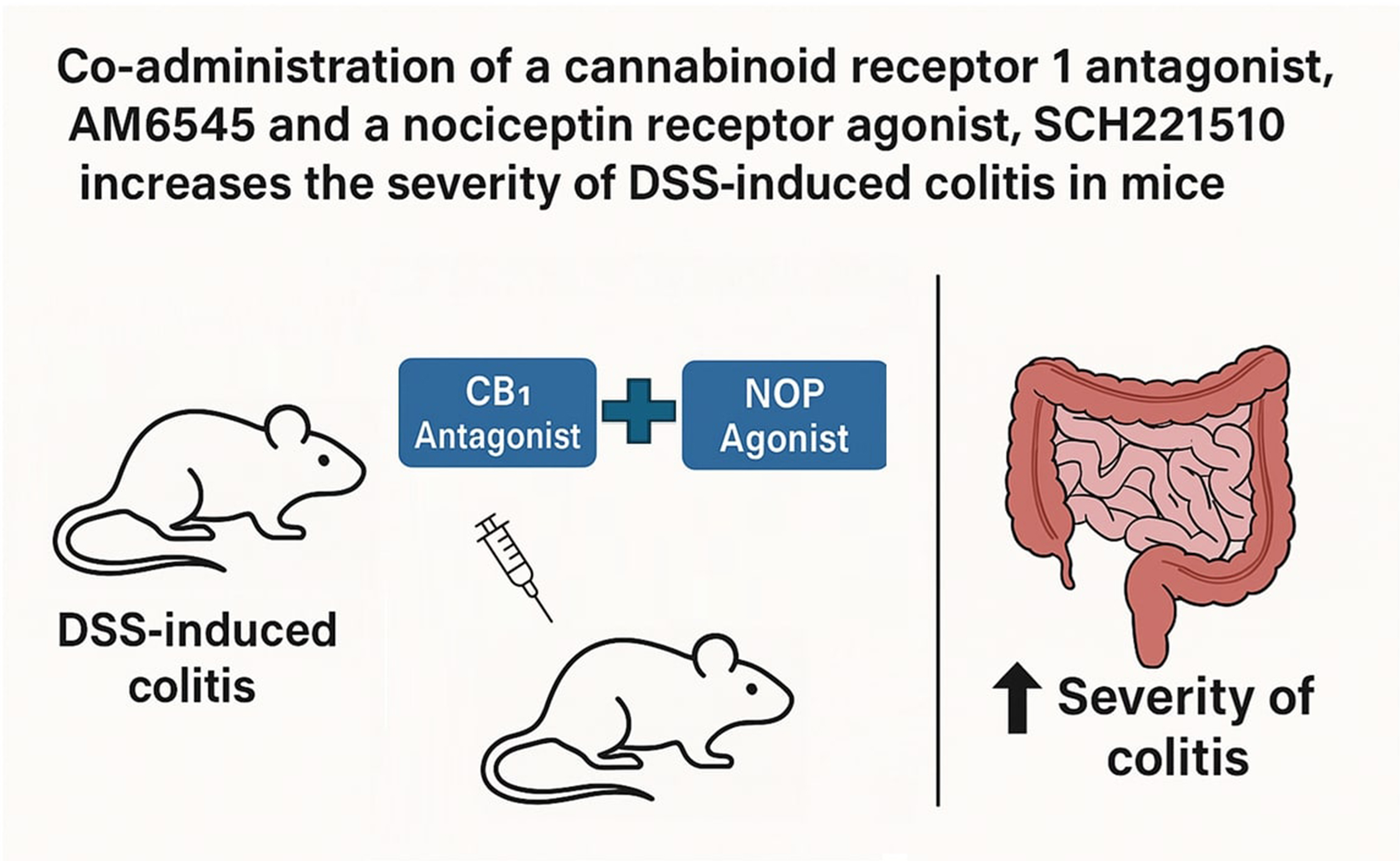

Abstract

Background. Despite the broad range of treatment options available for intestinal inflammation, the development of novel therapeutics remains essential due to the diminishing effectiveness of current therapies over time. Both the endocannabinoid system (ECS) and nociceptin/orphanin FQ peptide (NOP) receptors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diseases associated with intestinal inflammation, highlighting their potential as therapeutic targets.

Objectives. We hypothesized that an interaction exists between cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2) and the NOP receptor, which may hold therapeutic relevance for the treatment of colitis.

Materials and methods. In this study, we used 3 selective ligands: a CB1 antagonist (AM6545), a CB2 antagonist (AM630) and a NOP agonist (SCH221510) in a mouse model of colitis induced by 3% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS). Quantification of several secondary messengers was conducted using western blot analysis. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was employed to assess CB1 expression levels in colonic tissue, while liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was used to evaluate the concentrations of endocannabinoids and related lipid mediators.

Results. We observed a statistically significant increase in the macroscopic score and a nonsignificant increase in the microscopic score in inflamed mice treated with both AM6545 and SCH221510 compared to those treated with SCH221510 alone. Additionally, the combination-treated group exhibited significantly lower levels of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) and significantly higher levels of phosphorylated protein kinase B (p-AKT) and β-arrestin relative to the SCH221510-only group.

Conclusions. Our study offers novel insights into the interaction between the ECS and the NOP receptor, which may inform the development of new therapeutic strategies for inflammatory conditions such as colitis.

Key words: nociceptin, colitis, cannabinoid

Background

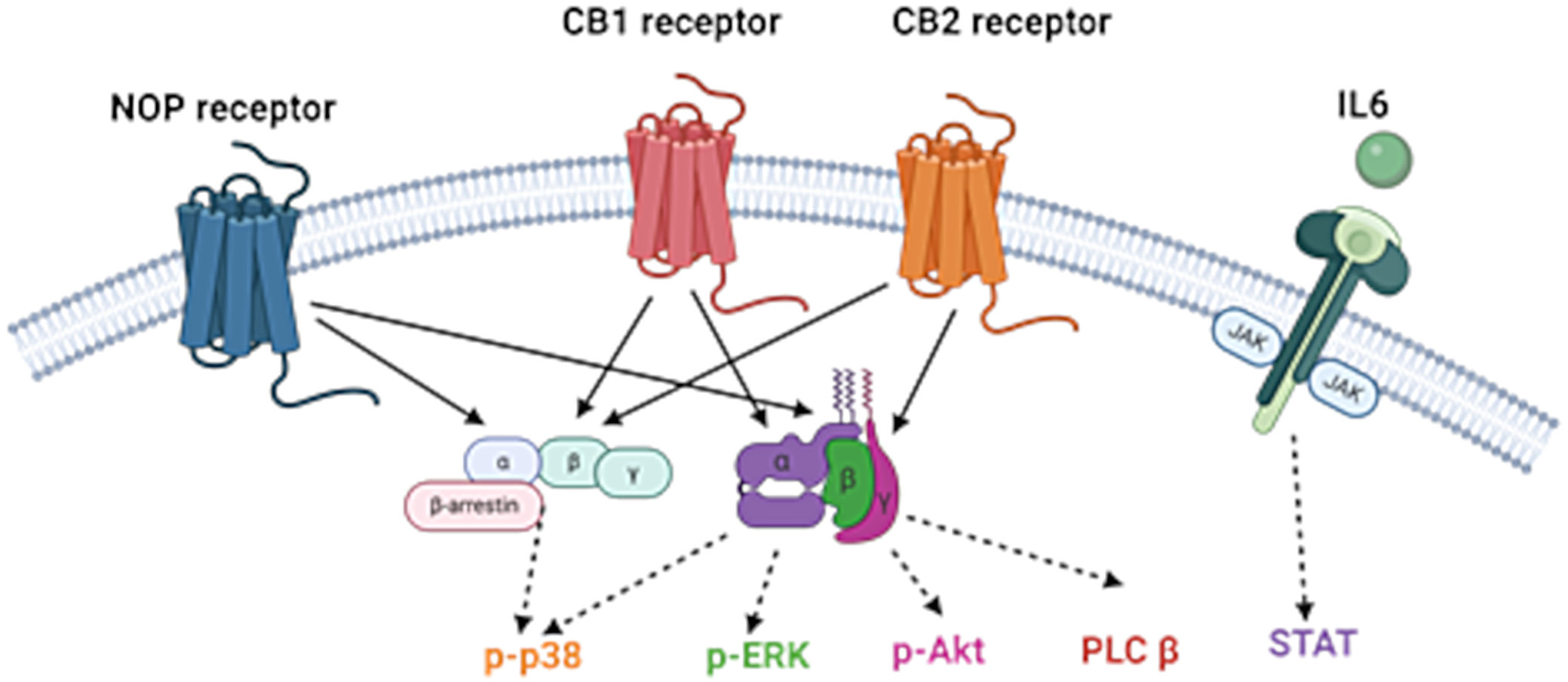

Despite the wide variety of treatment options for intestinal inflammation, novel therapeutics is still under development due to the loss of efficacy and adverse effects of the current therapies. Both the endocannabinoid (eCB) system (ECS) and the nociceptin receptor (NOP) are implicated in the pathogenesis of diseases associated with intestinal inflammation, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The ECS consists of receptors, endogenous cannabinoid ligands (eCBs) and enzymes that metabolize the ligands. The “classical” endocannabinoid receptors consist of 2 G protein-coupled receptors: cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2). The ECS is part of a larger network of lipid molecules (the endocannabinoidome (eCBome)), which partly share receptors and, particularly, biosynthetic and catabolic pathways with eCBs.1 Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) is primarily expressed in the central nervous system, whereas cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) is predominantly located in peripheral tissues, including immune cells and the mucosa of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Within the GI tract, CB1 is mainly localized in the enteric plexus,2 while CB2 expression is largely restricted to the lamina propria.3

Modulation of cannabinoid receptors has proven highly effective in alleviating intestinal inflammation in animal models.4, 5 In a study by Massa et al.6 using a 2,4-dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (DNBS)-induced colitis model in mice, treatment with the CB1 agonist HU210 provided significant protection against colitis, while administration of the CB1 antagonist SR141716A worsened inflammation. Additionally, Singh et al.7 demonstrated that the CB2 agonist JWH-133 markedly reduced inflammation in both a dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis model and in interleukin (IL)-10-deficient mice, compared to controls.

The ECS has been shown to engage in crosstalk with other signaling systems, including the endogenous opioid system (endorphins). The opioid receptor family consists of 4 major subtypes: delta (DOP), kappa (KOP), mu (MOP), and nociceptin/orphanin FQ peptide receptor (NOP). The interaction between the ECS and opioid receptors occurs at multiple levels, including direct receptor–receptor interactions and shared signal transduction pathways, as extensively reviewed by Scavone et al.8 Notably, most studies have focused on the interaction between the endocannabinoid system and the classical opioid receptors, i.e., DOP, KOP and MOP. Despite its structural similarity to other opioid peptides,9 nociceptin exclusively binds to NOP and does not interact with DOP, KOP or MOP receptors. Accordingly, no classical opioid ligand – such as dynorphin, β-endorphin or enkephalins – has been found to bind to the NOP receptor,10 which is now frequently excluded from the classical opioid receptor group. NOP has been extensively studied in the context of inflammatory conditions, including intestinal inflammation.11 Moreover, a functional connection between the ECS and NOP has been demonstrated in several studies. For example, Rawls et al.12 showed that activation of the NOP receptor is essential for cannabinoid agonists to induce hypothermia in rats. Similarly, Cannarsa et al.13 reported that Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) reduced NOP expression in the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line, an effect that was blocked by the selective CB1 antagonist AM251.

Objectives

Given the functional similarities between the eCB and NOP systems, as well as their reported anti-inflammatory properties, we hypothesized that interactions between CB1, CB2 and NOP receptors may offer therapeutic potential for the treatment of IBD. Therefore, we investigated the possible reciprocal actions between ECS and NOP in an animal model of colitis. We utilized AM6545, a peripherally restricted neutral antagonist for the CB1 receptor, chosen for its demonstrated efficacy in other inflammation-related models.14, 15 AM630 was selected as the CB2 receptor ligand, based on its demonstrated effectiveness in various studies, including its ability to reverse the anti-inflammatory effects of the CB2 agonist JWH-133 in chronic colitis observed in IL-10–/– mice.7 SCH221510 was selected as a selective NOP receptor ligand based on the findings of Sobczak et al.16, who demonstrated that systemic administration of this compound significantly reduced inflammation in mice with 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis – an effect that was reversed by the selective NOP antagonist J-113397. Figure 1 shows the biological roles of CB1, CB2 and NOP in inflammatory pathways.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male BALB/c mice were sourced from the vivarium at the University of Lodz, Poland. The mice weighed approx. 22 g and were 6–8 weeks old. They were housed in plastic cages lined with sawdust, maintained at a constant temperature of 22°C, under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 5:00 AM). The mice had free access to chow pellets (Agropol S.J., Motycz, Poland) and tap water. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Medical University of Lodz (protocol No. 2/LB191/2021) and conducted in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 22 September 2010 (2010/63/EU). Measures were taken to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used. Each in vivo experiment involved groups of 4–10 mice. The colitis induction and procedures were performed in Animal Research Facility at the Medical University of Lodz. All sections of this project adhered to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines for animal research.17

Induction of colitis and evaluation of macro- and microscopic score

Experimental colitis was induced by administering 3% DSS in the drinking water for 5 days, as previously described.18 On day 5, DSS was replaced with tap water. Treatments were administered from day 3 to day 6. SCH221510 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) was selected as a selective NOP receptor agonist. AM6545 and AM630 (both from Tocris Bioscience) were used as selective antagonists for CB1 and CB2, respectively. The control group received vehicle administration, while the following ligand doses were used: SCH221510 at 3 mg/kg, AM6545 at 3 mg/kg and AM630 at 5 mg/kg.16, 19, 20 All compounds were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) twice daily for 4 consecutive days.

On day 7, animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and macroscopic assessments were performed, including evaluation of colon length, degree of inflammation, and the presence of erythema, ulceration, necrosis, as well as the depth and surface area of lesions. Colonic samples for histological evaluation and further tests were collected and respective analyses were performed. Sections of the distal colon were flattened with the mucosal side up, stapled onto cardboard strips and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for at least 24 h at 4°C. After fixation, the tissues were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm sections, mounted onto slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The slides were reviewed in a blinded manner using a Zeiss Axio Imager 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany). Images were captured with a digital camera connected to an image analysis software system. The microscopic total damage score was assessed using an established scoring system,21 evaluating parameters such as muscle thickening, cellular infiltration, destruction of mucosal architecture, goblet cell depletion, and the presence of crypt abscesses.

Western blot analyses

Colonic tissue was homogenized using the Precellys Evolution tissue homogenizer (Bertin Instruments, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) in 10 volumes of lysis buffer containing 150 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 2 mM Tris-EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 1% Igepal, 2.5% deoxycholic acid, and 10 µL of 1× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, Poznań, Poland). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Protein concentration in supernatants was then quantified using Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Separation of proteins (20 mg/well) was performed on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (20–40 mA/gel) in electrophoretic buffer (0.1% SDS, 192 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris, pH 8.3). Proteins separated by electrophoresis were transferred to Invitrolon membranes using a semi-dry electroblotting system (pore size, 0.45 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in transfer buffer containing 20% (v/v) methanol, 192 mM glycine and 25 mM Tris, with a pH 8.3. The membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in 5% non-fat dry milk Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST; 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) to saturate non-specific protein binding sites. Membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies specific to the following proteins: anti-extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) (ab86299; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (sc-8019; Santa Cruz, Dallas, USA) and anti-β-arrestin-1 (ab31868; Abcam), at 4–8°C. An anti-β-actin antibody (sc-47778; Santa Cruz) was used as a loading control. Appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was applied for 1 h at room temperature and then the bands were visualized using a Super-Signal™ West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as a substrate for the localization of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) activity. Qualitative and quantitative analysis was performed by measuring integrated optical density (IOD) using GelProAnalyz-er v. 3.0 for WindowsTM program (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, USA).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription and real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the Total RNA Mini Plus Kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland). Briefly, tissue samples were homogenized in 400 µL of lysis buffer containing Fenozol Plus reagent. The homogenates were subsequently centrifuged, and the supernatants were collected and washed. The purified RNA was subsequently eluted into collection tubes using 50 µL of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. The quantity and purity of the isolated RNA were measured using a spectrophotometer (BioPhotometer; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). For complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) synthesis, 1 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the Maxima cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following incubation conditions: 10 min at 25°C, 120 min at 37°C and 5 min at 85°C. Quantitative analysis was performed using TaqMan fluorescent probes on a Mastercycler® ep realplex4 S system (Eppendorf) to assess the expression of mouse CB1 (cnr1), with hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (hprt1) used as the endogenous control. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. The threshold cycle (Ct) values of the target genes were normalized to the Ct values of the housekeeping gene hprt1. The relative messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels were calculated using the formula 2^(–ΔCt) × 1000.

Quantitative analysis of eCBs and eCB-like mediators

The extraction, purification and quantification of eCBs from tissues were conducted following previously established procedure.22 In summary, tissues were homogenized and subjected to extraction with a mixture of chloroform, methanol and Tris–HCl (50 mmol/L, pH 7.5) in a 2:1:1 (vol/vol) ratio. The extraction solvent contained 15 internal standards: d8-arachidonoylethanolamide (d8-AEA) at 5 pmol, d5-2-arachidonoylglycerol (d5-2-AG), d4-palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) and d2-oleoylethanolamide (OEA) at 50 pmol each, and d4-docosahexaenoyl ethanolamide (DHA-EA) and d4-eicosapentaenoic ethanolamide (EPA-EA) at 10 pmol each (all standards were obtained from Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA). The lipid-containing organic phase obtained after extraction was dried down, weighed and subjected to pre-purification through open-bed chromatography on silica gel. Fractions were collected by eluting the column with chloroform/methanol mixtures in ratios of 99:1, 90:10 and 50:50 (v/v). The 90:10 fraction was utilized for the quantification of 2-AG, AEA, DHA-EA, EPA-EA, OEA, and PEA using liquid chromatography–atmospheric pressure chemical ionization–mass spectrometry (LC/APCI-ITMS). This involved using a Shimadzu high-performance liquid chromatography apparatus (LC10ADVP) coupled to a Shimadzu (LCMS-2020) quadrupole mass spectrometry through a Shimadzu atmospheric pressure chemical ionization interface (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). Mass spectrometry detection was performed with the following m/z values: 356 and 348 (molecular ions + 1 for d8-AEA and AEA), 304 and 300 (molecular ions + 1 for d4-PEA and PEA), 330 and 326 (molecular ions + 1 for d4-OEA and OEA), 376 and 372 (molecular ions + 1 for d4-DHA-EA and DHA-EA), 384 and 379 (molecular ions +1 for d5-2-AG and 2-AG), and 346 and 350 (molecular ions + 1 for d4-EPA-EA and EPA-EA). Liquid chromatography analysis was conducted in the isocratic mode using a Discovery C18 column (Supelco, Sigma-Aldrich, Prague, Czech Republic) (15 cm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) with methanol/water/acetic acid (85:15:1 by vol) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The levels of eCBs and eCB-like compounds in tissues were quantified using isotope dilution with the deuterated standards mentioned earlier, and results were expressed as pmol per mg of tissue weight.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism v. 8.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, USA). Due to the small sample size per group, which limited the ability to reliably assess normality, the Kruskal–Wallis test was employed for multiple group comparisons. Results are presented as the χ2 test statistic (H), including degrees of freedom (df) and p-value, with post hoc analysis performed using Dunn’s test. Data are presented as median values with corresponding minimum and maximum ranges. Outliers were identified and excluded using the Robust Regression and Outlier Removal (ROUT) method. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

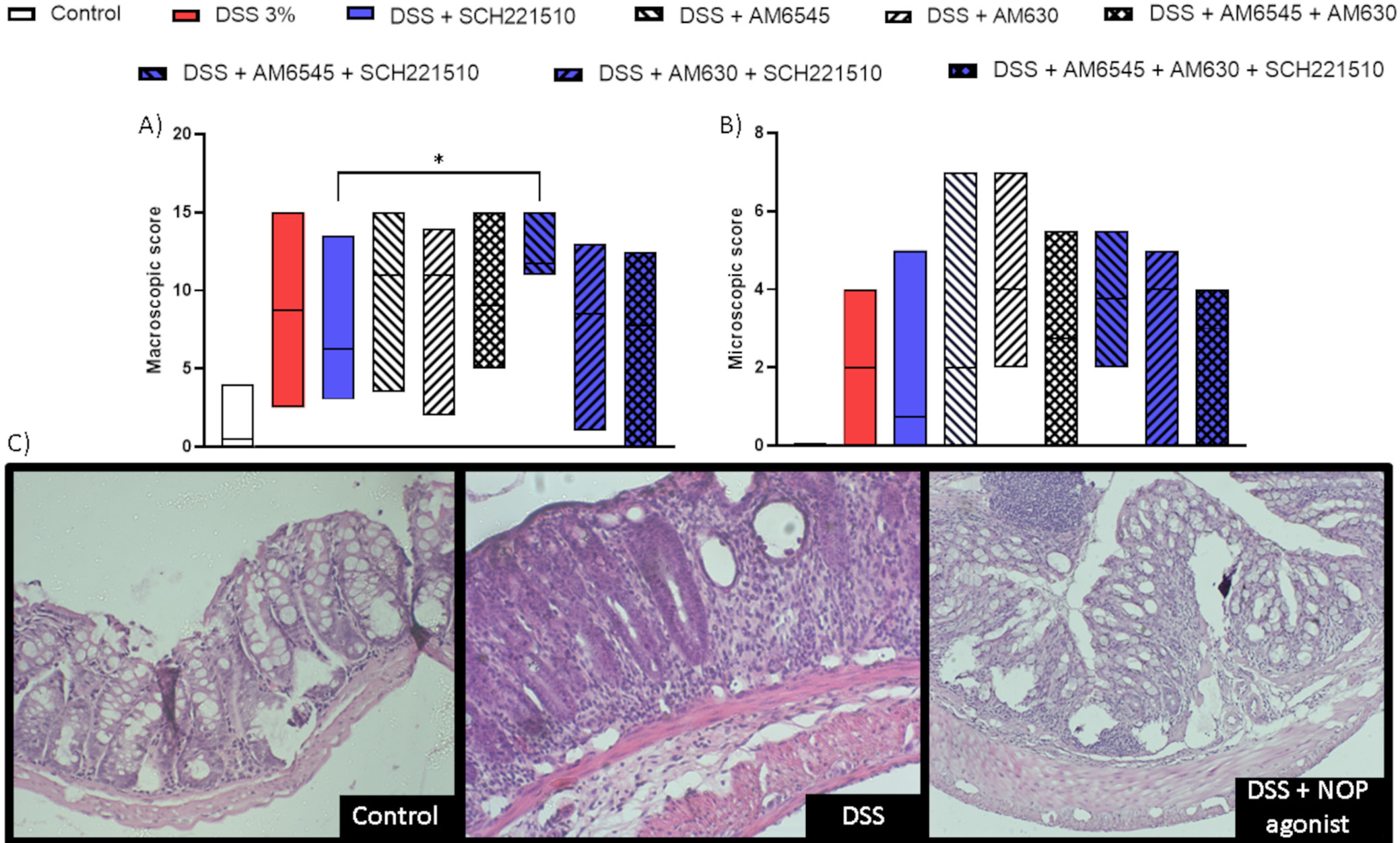

First, we performed a mouse semi-chronic model of colitis induced using DSS with selective ligands of CB1, CB2 and NOP receptors (AM6545, AM630 and SCH221510, respectively) given alone or in combination. A statistically significant increase in the macroscopic score was observed in inflamed mice treated with SCH221510 + AM6545, but not with SCH221510 + AM630, when compared to mice treated with SCH221510 alone (H(8) = 35.52, p < 0.001; Dunn’s test: 11.75 (11.00–15.00) vs 6.25 (3.00–13.50), p = 0.032; Figure 2A, Table 1).

Concurrently, only a nonsignificant increase in the microscopic score was found in mice treated with SCH221510 + AM6545 compared to mice treated only with SCH221510 (H(8) = 16.33, p = 0.03; Dunn’s test: 3.75 (2.00–5.50) vs 0.75 (0.00–5.00), p > 0.083; no significance between groups was achieved as assessed with Dunn’s test; Figure 2B,C, Table 1). Thus, for further experiments, we chose AM6545.

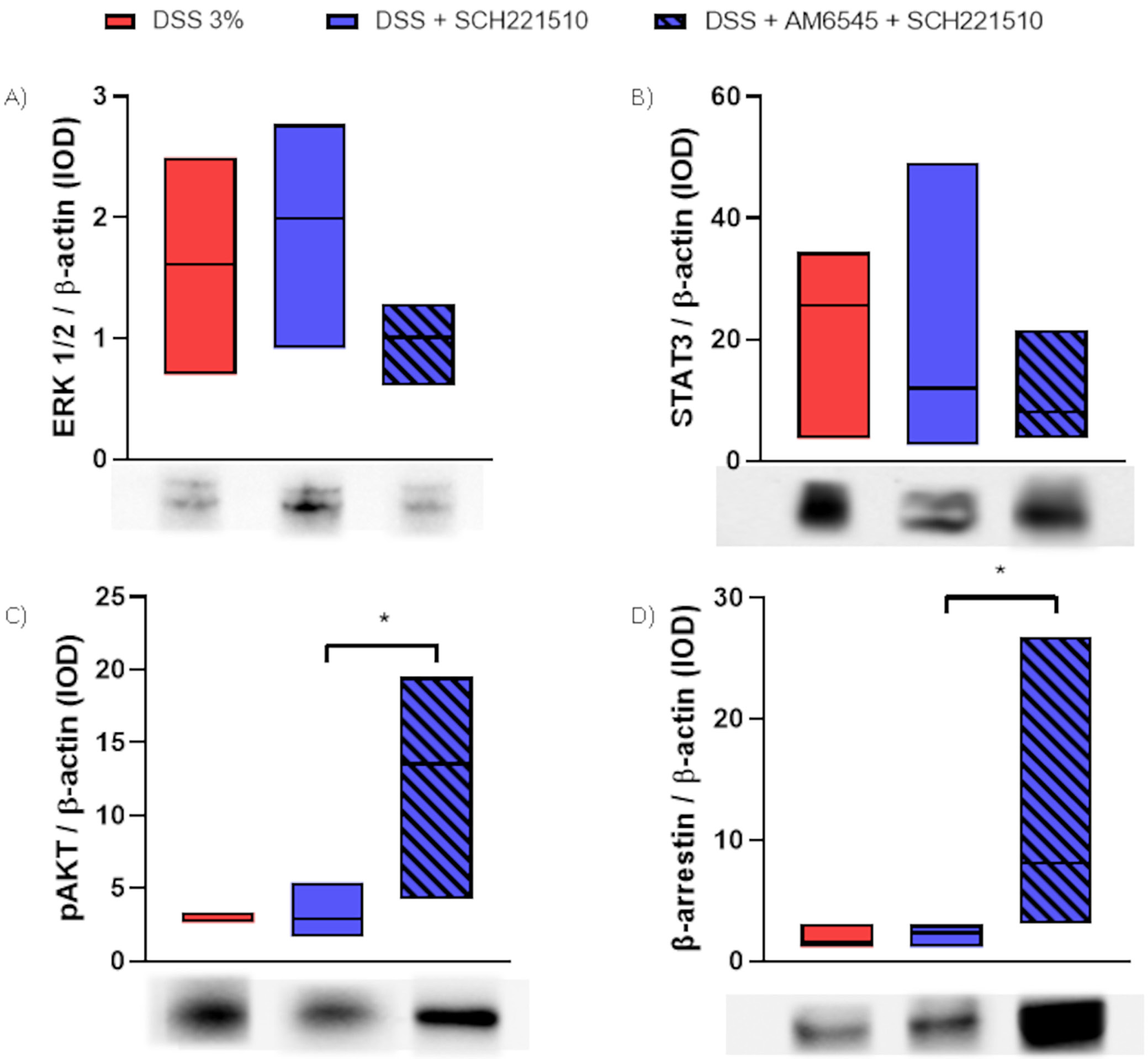

Next, we investigated the protein levels of a few secondary messengers in mice treated with SCH221510, AM6545 (alone or with combination) or vehicle (Figure 3A–D, Table 1). We found a reduction in the levels of ERK 1/2 in mice treated with SCH221510 + AM6545 compared to mice treated with SCH221510 solely (H(2) = 2.99, p = 0.23; Dunn’s test: 1.01 (0.61–1.28) vs 1.99 (0.91–2.77), p > 0.252). A similar trend was noticed when we assessed STAT3 (H(2) = 1.52, p = 0.50; Dunn’s test: 8.04 (3.70–21.61) vs 11.97 (2.65–49.12), p > 0.999) in mice treated with SCH221510 + AM6545 or SCH221510 only, respectively. Conversely, we observed a significant increase in the levels of β-arrestin in mice treated with SCH221510 + AM6545 compared to mice treated with SCH221510 only (H(2) = 7.47, p = 0.01; Dunn’s test: 8.07 (3.00–26.77) vs 2.35 (1.14–3.01), p = 0.047), as well as in the levels of phospho-AKT (pAKT) (H(2) = 8.23, p = 0.006; Dunn’s test: 13.52 (4.19–19.52) vs 2.91 (1.67–5.40), p = 0.031).

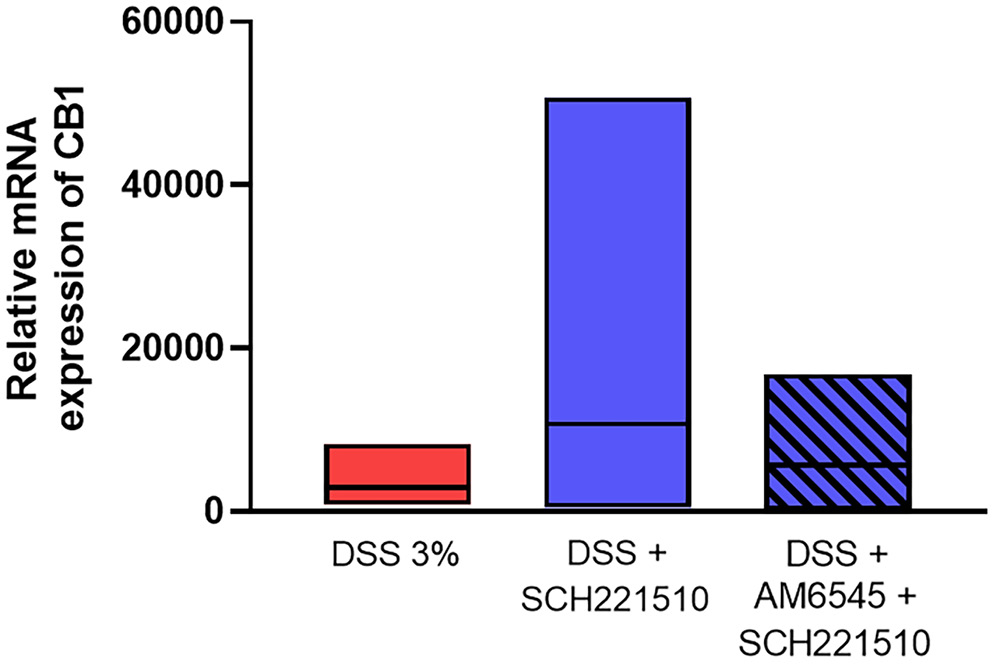

Next, we proceeded to examine the relative expression of CB1 receptor in the studied groups. We found that SCH221510 increased the relative expression of CB1 in inflamed mouse colon compared to mice treated with vehicle (H(2 = 1.74, p = 0.42; Dunn’s test: 10736 (448–50738) vs 2888 (807–8282), p > 0.999), although in statistically nonsignificant manner (Figure 4, Table 1)

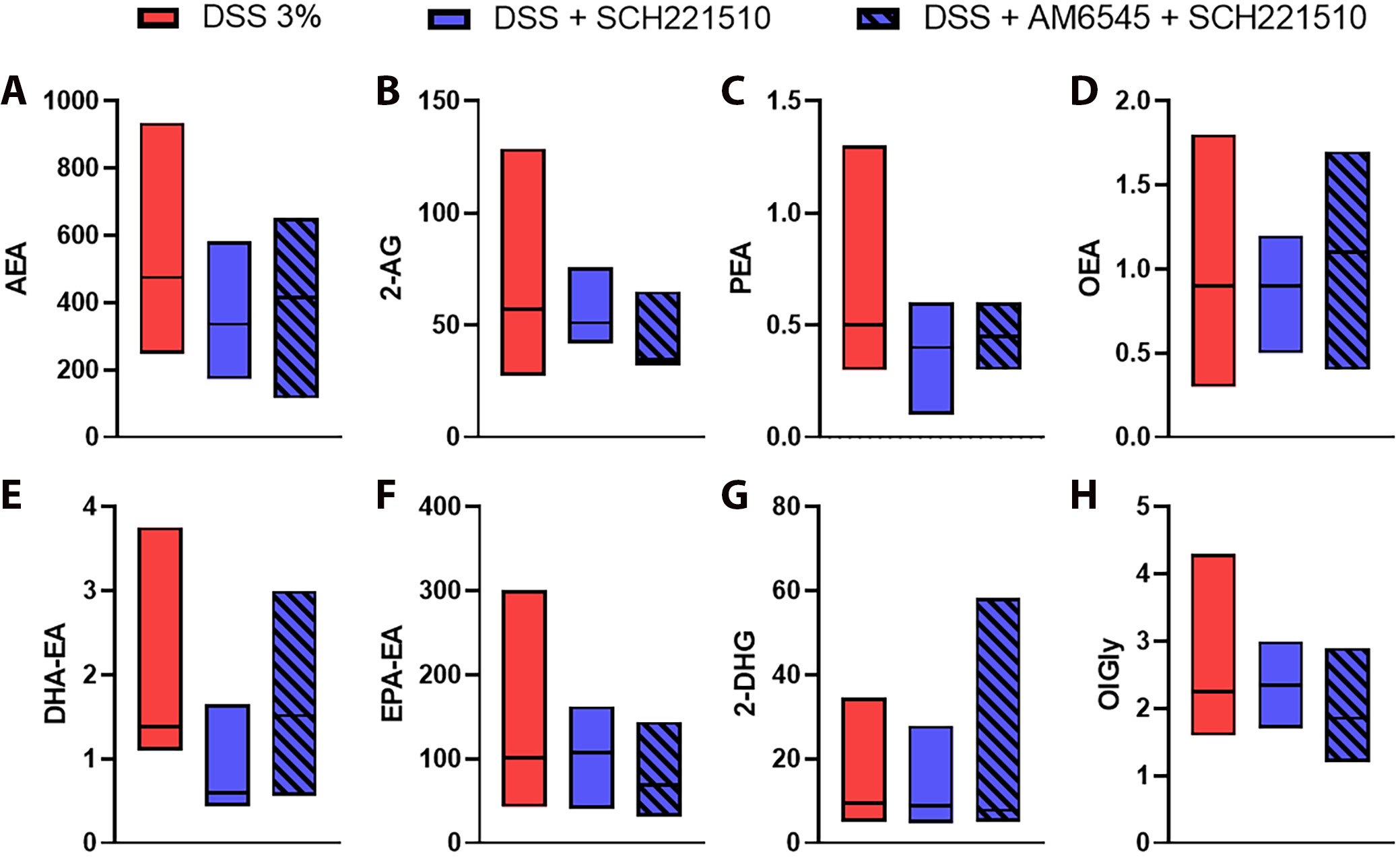

Lastly, we investigated the levels of eCBs and eCBome mediators in mice administered with DSS and treated with SCH221510 and SCH221510 + AM6545. We found no statistically significant difference comparing mice treated with SCH221510, alone or in combination with AM6545 (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

This is the first study to address the in vivo crosstalk between the components of the eCB and NOP systems. We showed that selective blockade of the CB1 receptor in combination with SCH221510, a selective NOP ligand, unlike the latter agonist alone, exacerbates inflammation in a semi-chronic model of colitis induced with DSS assessed macro- and microscopically. The interaction probably occurs at the cellular level as the extent of activation of 2 assessed secondary messengers (ERK1/2 and β-arrestin) was found to be different between the mice treated with NOP agonist + CB1 antagonist and the NOP agonist only. ERK-dependent signaling was shown to be a major signaling pathway regulating nociceptin and its receptor in human peripheral leukocytes, as selective blockage of ERK prevented the phor-bol-12-myristate-13-acetate induced downregulation of NOP mRNA.23 ERK1/2 is also one of the major players in CB1-related signaling pathways as acute stimulation with THC increases ERK1/2 activation in the dorsal striatum24 and hippocampus.25 β-arrestin is also a crucial messenger in NOP26 and CB127 signaling. In our study, we observed a decrease in ERK1/2 levels and a significant increase in β-arrestin levels after the administration of AM6545. Both effects may result from AM6545 counteracting the endocannabinoid-mediated activity of CB1, potentially contributing to the exacerbation of inflammation observed with the antagonist. This antagonistic action may also interfere with the protective effects of SCH221510 in inflamed mice. Additionally, co-administration of SCH221510 and the CB1 antagonist was associated with increased Akt phosphorylation, further supporting this interaction.

Although we did not observe a statistically significant difference, the increase in relative mRNA expression of CB1 in inflamed mice treated with the NOP receptor agonist was evident. The levels of CB1 expression in inflamed mice receiving vehicles were similar to those treated with a combination of NOP agonist and CB1 antagonist. The results are contrary to the effects reported in the literature, which consistently show an increase in CB1/2 expression in active disease and downregulation of these receptors in quiescent disease.28, 29 In 1 study, a dose-dependent downregulation of NOP expression was found after treatment with THC, and the effect was abolished by the co-administration of AM251, a potent CB1 antagonist.13 Taken together, a dependency between the assessed receptors on CB1 mRNA levels is evident but further in vitro studies are warranted to fully elucidate this phenomenon, which: 1) in view of the anti-inflammatory effects of CB1 receptors mentioned above, might contribute to the exacerbation of inflammation-counteraction of SCH221510 protective effect, observed with the CB1 antagonist, and 2) would be in agreement with the reduction of ERK1/2 activity and increase of β-arrestin levels observed here.

Conflicting results regarding the expression levels of CB1/CB2 and eCBs in patients with IBD are evident in the literature. For instance, Di Sabatino et al.30 reported increased CB1 expression and stable levels of 2-AG and PEA in inflamed and uninflamed tissue of patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, while the level of AEA was decreased in inflamed tissue. Conversely, Grill et al.31 found that CB1 transcripts in IBD are downregulated compared to healthy controls. D’Argenio et al.4 presented results indicating an increase in AEA levels in the inflamed rectum or the most inflamed area in patients with UC. We concluded our project by thoroughly evaluating the level of eCBs and eCB-like mediators using high-performance liquid chromatography. Our aim was to assess whether the results observed in the previous experiments are influenced by the level of eCBs. No statistically significant differences were observed, suggesting that the anti-inflammatory effects of NOP receptor activation, either alone or in combination with CB1 blockade, are not mediated by changes in the colonic levels of these inflammatory markers.

Limitations

We acknowledge the limitations of our study, with the primary drawback being the difficulty in specifically elucidating the interaction between the ECS and the NOP receptor. The complexity of the ECS, encompassing both classical and non-classical cannabinoid receptors, a diverse range of ligands, and multiple enzymes involved in their synthesis and degradation, posed a significant challenge in the absence of prior detailed research in this area. Thus, the primary goal of the study was to assess the level at which the interaction between cannabinoid receptors and NOP occurs. By conducting experiments fully in vivo, we succeeded in demonstrating significant differences in secondary messengers in the chosen model. One possible explanation for our observation is that CB1 and NOP form heterodimers under certain conditions, exhibiting distinct biological effects. Importantly, it has been demonstrated that opioid receptors, NOP and CB1, can heterodimerize with other receptors. For instance, Evans et al.32 showed that prolonged NOP activation in cells expressing either opioid receptors or NOP results in the internalization of opioid receptors, while activation of opioid receptors leads to the internalization of NOP receptors. Interaction of µ-opioid receptor/NOP heterodimers with N-type calcium channels and their internalization. This phenomenon occurred exclusively in the presence of NOP. On the other hand, in the case of CB1/µ-opioid heterodimer, activation of either receptor alone within the heterodimer elicited effective Gi signaling. Conversely, the co-activation of both receptors led to the inhibition of their Gi-mediated responses.33 Advanced methods such as immunofluorescence, crystallography, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations34, 35 are the next steps to reveal the structural features responsible for this reciprocal activity between CB1 and NOP, and the possibility for heterodimerization of both receptors.

Conclusions

Our study offers new insights into the interaction between the ECS and NOP system in the context of intestinal inflammation. We hope that the present results will help pave the way to further specific research in this field and to reconsider the ECS as a possible therapeutic target for intestinal inflammation. Indeed, targeting this system in IBD was originally regarded as a promising approach in preclinical studies, but it ultimately failed as results in patients with IBD were unsatisfactory.36 This was due, at least in part, to central nervous system adverse effects observed following treatment with CB1 receptor agonists, which consequently have a narrow therapeutic window in this and other disorders. A deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of the ECS in IBD may lead to the development of more effective therapeutics. For example, the use of endocannabinoid degradation inhibitors or peripherally restricted CB1 agonists, either indirectly enhancing CB1 receptor activation or selectively targeting peripheral CB1 receptors, offers the potential to avoid the central nervous system side effects associated with brain-penetrant CB1 agonists.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14176773. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Results of Dunn’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons, performed following the Kruskal–Wallis test, to analyze group differences in endocannabinoid level analyses.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.