Abstract

Background. Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is an important treatment modality in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by reducing respiratory distress, improving gas exchange and reducing exacerbations without the need for intubation and invasive airways.

Objectives. To synthesize data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and perform a meta-analysis to understand the beneficial effects of NIV across different COPD stages.

Materials and methods. A systematic literature review was performed using MEDLINE (PubMed) and Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) al databases for RCTs that involved the administration of NIV vs usual treatment (oxygen supplementation, pharmacological agents, nasal cannulation) in patients with stable COPD, acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD), and post-exacerbation COPD (PECOPD). Mortality, exacerbation and intubation rates, and arterial blood gases (PaCO2 and PaO2 levels) were assessed in both groups. RevMan software was used to assess the risk of bias and calculate the pooled odds ratio (OR), mean differences (MDs) and subgroup analyses with a random-effects model.

Results. A total of 51 RCTs were included in the meta-analysis with information from 3,775 patients. Meta-analysis of the data showed that there was a significant decrease in mortality outcomes (p < 0.001), intubation frequency (p < 0.001) and PaCO2 levels (p < 0.001) but no significant improvement in exacerbation frequency (p = 0.12) and PaO2 levels (p = 0.69). Subgroup analyses demonstrated no significant difference between COPD stage on mortality outcomes (p = 0.32), PaCO2 level (p = 0.12) and PaO2 level (p = 0.64). There was a significant decrease in intubation rate in AECOPD patients receiving NIV and a statistically nonsignificant difference in exacerbation frequency in stable COPD patients using NIV.

Conclusions. The findings of this meta-analysis indicate a substantial overall enhancement in the frequency of exacerbations and intubations, mortality outcomes, and arterial gas levels among patients in various stages of COPD. Consequently, it is imperative to identify patients with COPD that are most likely to benefit from the use of NIV.

Key words: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, exacerbation, noninvasive ventilation, arterial blood gases, BiPAP

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), encompassing emphysema and chronic bronchitis, is a common, progressive disorder characterized by irreversible airflow limitation resulting from damage to both the airways and the lung parenchyma.1, 2 Globally, COPD remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, responsible for an estimated 3.1 million deaths in 2021, with the heaviest burden observed in low- and middle-income countries.3 Beyond its mortality toll, COPD significantly impairs daily functioning and quality of life, and drives substantial healthcare utilization through recurrent exacerbations that often necessitate hospitalization and intensified pharmacotherapy.4

Key risk factors for COPD encompass cigarette smoking; exposure to ambient air pollution; a history of childhood asthma; and α1-antitrypsin deficiency, a rare genetic disorder.4 These insults provoke pathological remodeling of the lung parenchyma, including destruction of alveolar walls, that impairs gas exchange, precipitating hypoxemia and hypercapnia, and in severe cases leading to acute hypercapnic respiratory failure (AHRF).5, 6 Resultant hypoxemia and systemic inflammation manifest as respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, fatigue, wheezing, cough, and chest tightness) and drive extrapulmonary complications, notably pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure, as well as adverse effects on endocrine, gastrointestinal, neuromuscular, and musculoskeletal systems.7, 8

Stable COPD refers to a state where symptoms are manageable and not worsening. Acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) is a sudden worsening of COPD symptoms. Post-exacerbation COPD (PECOPD) describes the recovery phase after an acute exacerbation. The diagnosis of COPD is based on symptom assessment, imaging tests, pulmonary function tests (spirometry), and physical examinations. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) has developed diagnostic criteria, including a post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio <0.7. The GOLD criteria also classify the severity of airflow limitations into various stages and are used with patient-reported outcomes and exacerbation history to guide COPD management decisions.2 Treatment plans for COPD aim to improve quality of life, alleviate symptoms and prevent disease progression.

Pharmacological management of acute COPD exacerbations typically includes systemic corticosteroids, inhaled short-acting bronchodilators, and antibiotics when there is clinical or microbiological suspicion of bacterial infection.9, 10 Adjunctive ventilatory support, preferentially noninvasive ventilation (NIV) in cases of hypercapnic respiratory failure, can avert the need for invasive mechanical ventilation, which is reserved for NIV failure or contraindications. However, systemic corticosteroids, while accelerating recovery and reducing relapse rates, carry risks of hyperglycemia, fluid retention and steroid-induced myopathy, and repeated high-dose bronchodilator use may precipitate tachycardia, tremor and tolerance. Pulmonary rehabilitation, although pivotal for restoring functional capacity and reducing future exacerbations, often struggles with poor adherence, transport barriers and limited program availability. Invasive mechanical ventilation requires endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy and increases the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia, barotrauma and prolonged weaning difficulties in COPD patients.

Noninvasive ventilation is an alternative to invasive ventilation techniques in which ventilator support (pressure-supported airflow) is provided through a noninvasive interface such as a nasal, oronasal or full-face mask to ventilator muscles. It is a comfortable alternative to intubation and avoiding immobility, and is used for managing conditions like acute COPD exacerbations and cardiogenic pulmonary edema-related respiratory failure. It reduces complications like ventilator-associated pneumonia and sinusitis by eliminating the need for sedation and endotracheal intubation, thereby minimizing hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) stays. Bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and negative pressure ventilation (NPV) are the most common types of NIV. BiPAP delivers 2 pressure levels for improved ventilation and airway stability, while CPAP provides constant pressure, typically used for milder respiratory issues and sleep apnea. The American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Journal guidelines recommend the use of BiPAP for acute-on-chronic respiratory acidosis secondary to COPD exacerbations. Studies have shown that NIV has reduced mortality outcomes in patients with acute exacerbations and decreased complications and length of hospital stay.11, 12, 13

Previous meta-analyses have shown mixed results regarding the benefits of NIV in stable COPD patients (generally defined as no exacerbation in last 4 weeks). In general, long-term or domiciliary NIV use resulted in a decrease in mortality and improved quality of life, whereas outcomes such as hospital admissions and gas exchange were variable.10, 14 Effects of NIV in AECOPD patients were associated with lower deaths, intubation rates, and hospital stays in a meta-analysis by Osadnik et al.9 In a meta-analysis comparing NIV with usual care in PECOPD patients, the exacerbation frequency was decreased when NIV was employed, with no significant differences in mortality rates or arterial gases.15 Thus, the beneficial effects of NIV in patients in different COPD stages are heterogeneous in terms of outcomes which can limit its applicability.

Objectives

This study aims to systematically synthesize and critically analyze the available literature on NIV across all GOLD stages of COPD, quantifying its effects on mortality, hospital length of stay, exacerbation frequency, arterial blood gas parameters, and health-related quality of life in both acute exacerbations and stable disease, while comparing different NIV modalities, initiation timings and ventilator settings by patient phenotype, and ultimately developing an evidence-based clinical framework to guide optimal NIV selection, timing and management in acute and chronic COPD.

Materials and methods

Study selection or inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared any type of NIV device (BiPAP, nocturnal) or administration device (full face, oronasal or nasal mask) with usual therapy such as oxygen supplementation, long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), pharmacological treatment (antibiotics, bronchodilators, steroids, theophylline, mucolytic agents, etc.), or sham NIV for our analysis. We included adult patients (≥18 years) with various phases of COPD, including stable COPD, PECOPD and AECOPD in our analysis. Patients diagnosed with COPD as per the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) system that uses the FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7 were included. Exclusion criteria included non-randomized studies and prospective and retrospective study designs.

Information sources

We conducted a systematic literature search of MEDLINE (PubMed) and Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in November 2024, encompassing the period of 1990–2024.

Search strategy

We conducted comprehensive searches of PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library from inception through May 2025 using both free-text keywords – “non-invasive ventilation,” “NIV,” “non-invasive positive pressure ventilation,” “BiPAP,” “VPAP,” “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” “pulmonary disease,” and “pulmonary emphysema” – and their corresponding Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. Titles and abstracts of all retrieved records were screened for relevance, and full texts of potentially eligible studies were reviewed in detail. To ensure completeness, we also examined the reference lists of included articles for additional reports (Table 1).

Data extraction process

Data extraction was performed using a standardized, pre-piloted form to capture key study characteristics and outcomes: study identifiers (authors, publication year), design (e.g. randomized trial, cohort study), intervention and comparator details, duration of follow-up, COPD phase (stable vs exacerbation), participant demographics (mean age), exacerbation frequency and severity, and arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) levels.

Data items

We analyzed the following outcomes – mortality, exacerbation frequency, endotracheal intubation rates, and arterial blood gas parameters (PaCO2 and PaO2) – comparing patients receiving NIV with control groups. Article screening and data extraction were performed by a single reviewer using the predefined extraction form to ensure consistency and completeness of the collected data.

Risk of bias assessment

We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool to assess the methodological quality of the included studies.16 This tool includes the following criteria: randomization, allocation concealment, blinding and completeness of follow-up. The risk of bias for each item was graded as high, low or unclear risk.

Quantitative data synthesis

We performed the meta-analysis and statistical calculations were performed using Review Manager (RevMan, v. 5; The Nordic Cochrane Center, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Binary outcomes such as mortality, exacerbation, and intubation rates were reported as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Meta-analyses for binary outcomes were done using a random-effects model (Mantel–Haenszel method). Continuous outcomes such as PaCO2 and PaO2 levels were reported as mean differences (MDs) with associated 95% CIs using the random-effects model (inverse variance method). Heterogeneity in the included studies was evaluated using I2 statistic, with small heterogeneity for I2 values of <25%, moderate heterogeneity for I2values of 25% to 50% and high heterogeneity for I2 values >50%.17 Forest plots were constructed and p < 0.05 was statistically significant. Subgroup analyses were also performed according to stage of COPD (stable COPD, PECOPD and AECOPD) and type of control treatment or comparator (pharmacological treatment + oxygen, LTOT, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), or only pharmacological treatment). Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s test and a funnel plot, where the log OR for each study was plotted against its standard error (SE) for the mortality outcome. The vertical line indicates the pooled OR representing the overall summary effect size.

Results

Identification of studies

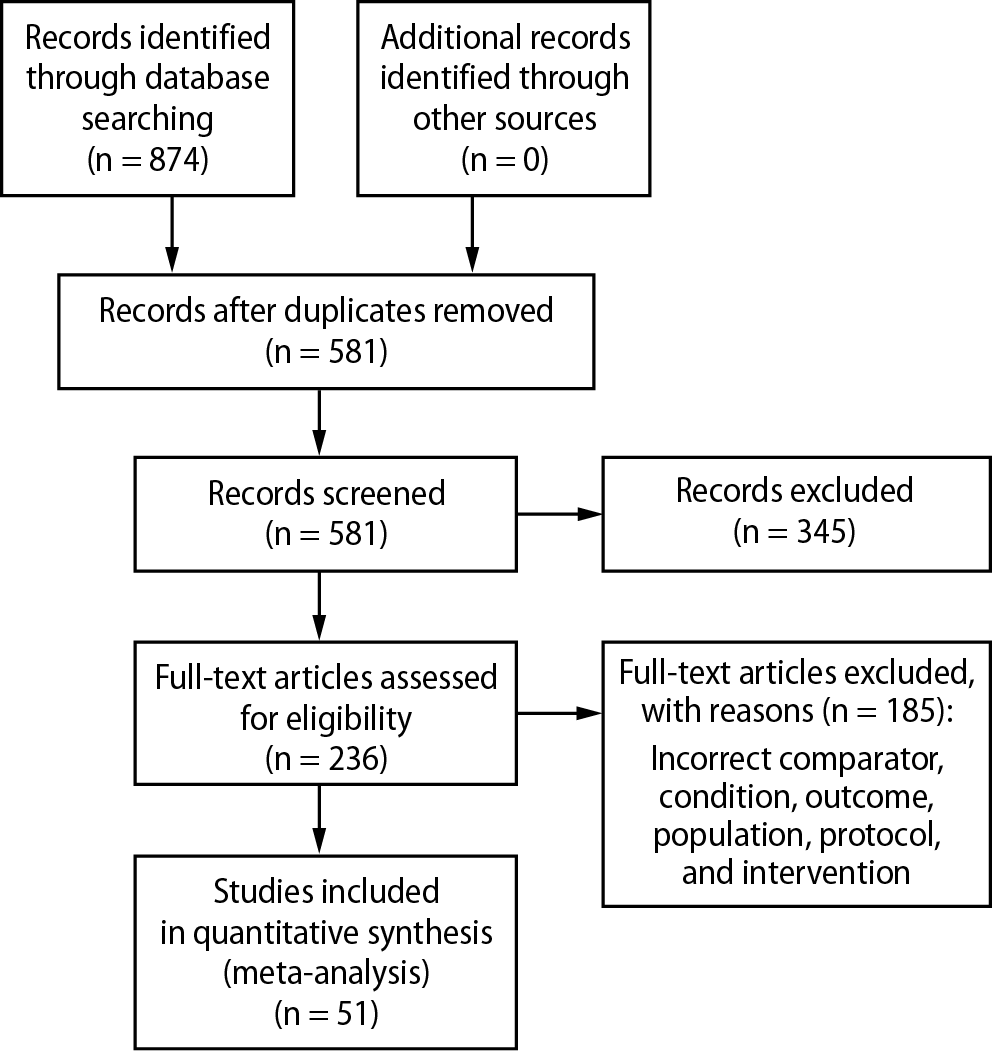

A total of 874 records were identified through database searching. After removing 345 duplicates and irrelevant records, 581 titles and abstracts were screened. Of these, 236 RCTs were assessed for eligibility. However, 185 RCTs were excluded due to reasons such as inappropriate comparator, intervention, condition, or population, missing required outcomes, or duplicate data. The selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. Table 2 shows the results of search strategy and Hits for COPD and NIV literature review.

Study characteristics

A total of 51 RCTs, comprising 3,775 participants, met the inclusion criteria. These included patients with stable COPD (n = 1,187), PECOPD (n = 1,314) and acute exacerbation of AECOPD (n = 1,274). The RCTs compared nocturnal or domiciliary NIV to other COPD treatments, such as LTOT, oxygen supplementation, pharmacologic therapies, HFNC, standard nasal cannula, or sham interventions. Participants were male and female across different COPD stages, with varying baseline PaCO2 levels, presence of hypercapnia, history of recent exacerbations, and differing durations of NIV administration and follow-up. Most studies used BiPAP systems for NIV delivery, administered via nasal, full-face or oronasal masks. Detailed information on interventions and control groups is provided in Table 3.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69

Characteristics of participants

The included studies involved patients with stable COPD (19 studies), PECOPD (14 studies) and AECOPD (18 studies). Across all studies, the mean age of participants was over 60 years. In most studies, baseline PaCO2 levels exceeded 6 kPa, and the majority of patients presented with hypercapnia (Table 4).18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69

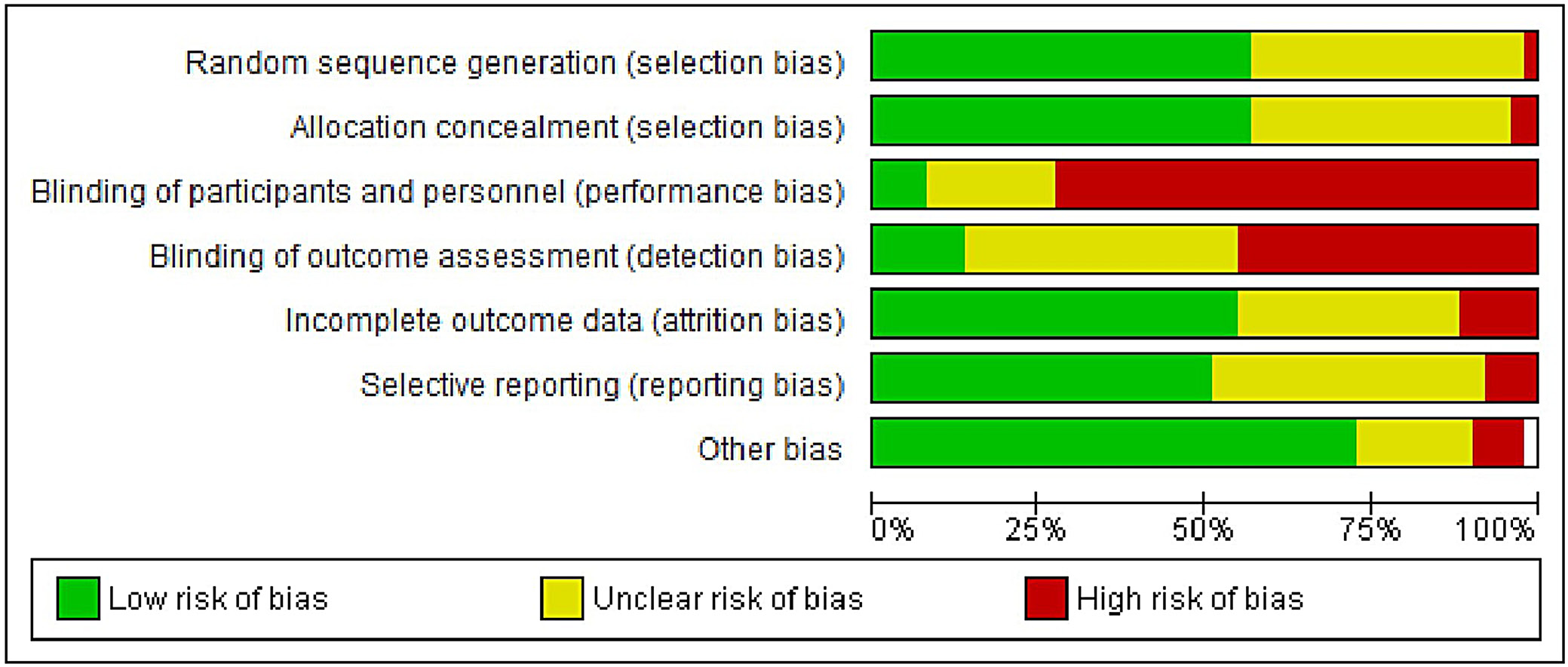

Bias assessment

The results of the risk of bias evaluation are presented in Figure 2. Overall, the studies demonstrated a high risk of detection and performance bias. This was primarily due to the inherent differences between NIV devices and their comparators, including interface types (e.g., nasal or oronasal masks), and the practical inability to blind participants and personnel to the intervention. These limitations may have influenced subjective and patient-reported outcomes. However, the funnel plot showed relative symmetry (Figure 3), and Egger’s test returned a p-value of 0.324, exceeding the conventional significance threshold of 0.05, suggesting a low risk of publication bias.

Meta-analysis results

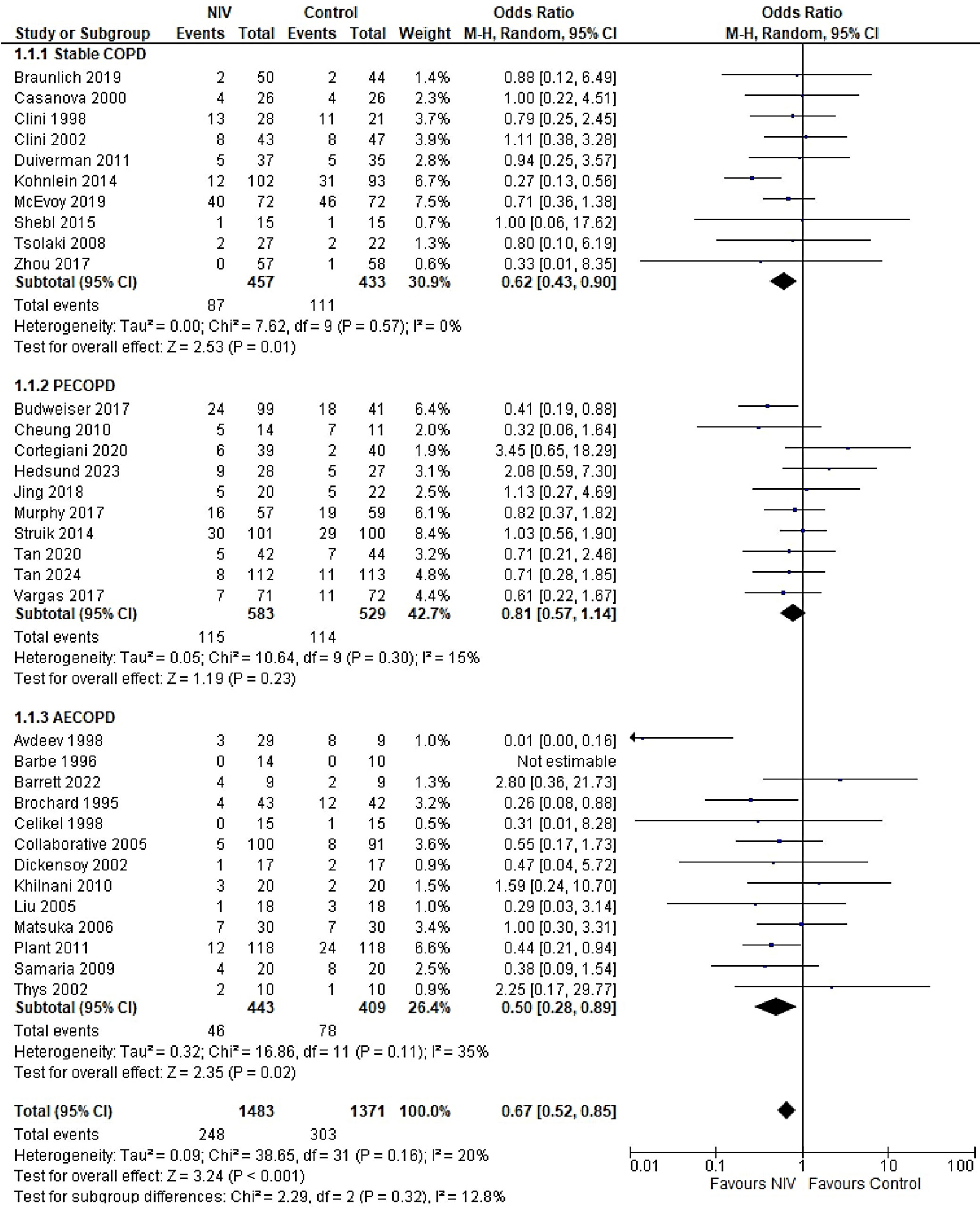

The overall risk of mortality was significantly lower in the NIV group compared to the control group (OR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.52–0.85, p < 0.001), with low heterogeneity observed across studies (I2 = 20%). However, when stratified by COPD stage, the difference in mortality was not statistically significant (p = 0.32). Mortality outcomes were reported across all COPD subgroups, each exhibiting low-to-moderate heterogeneity (I2 range: 0–35%). The highest heterogeneity was observed in the AECOPD subgroup (I2 = 35%), possibly due to variations in follow-up duration (Figure 4). The funnel plot for mortality outcomes demonstrated approximate symmetry, suggesting a low risk of publication bias, which was supported by Egger’s test results: stable COPD (p = 0.136), PECOPD (p = 0.211) and AECOPD (p = 0.141) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

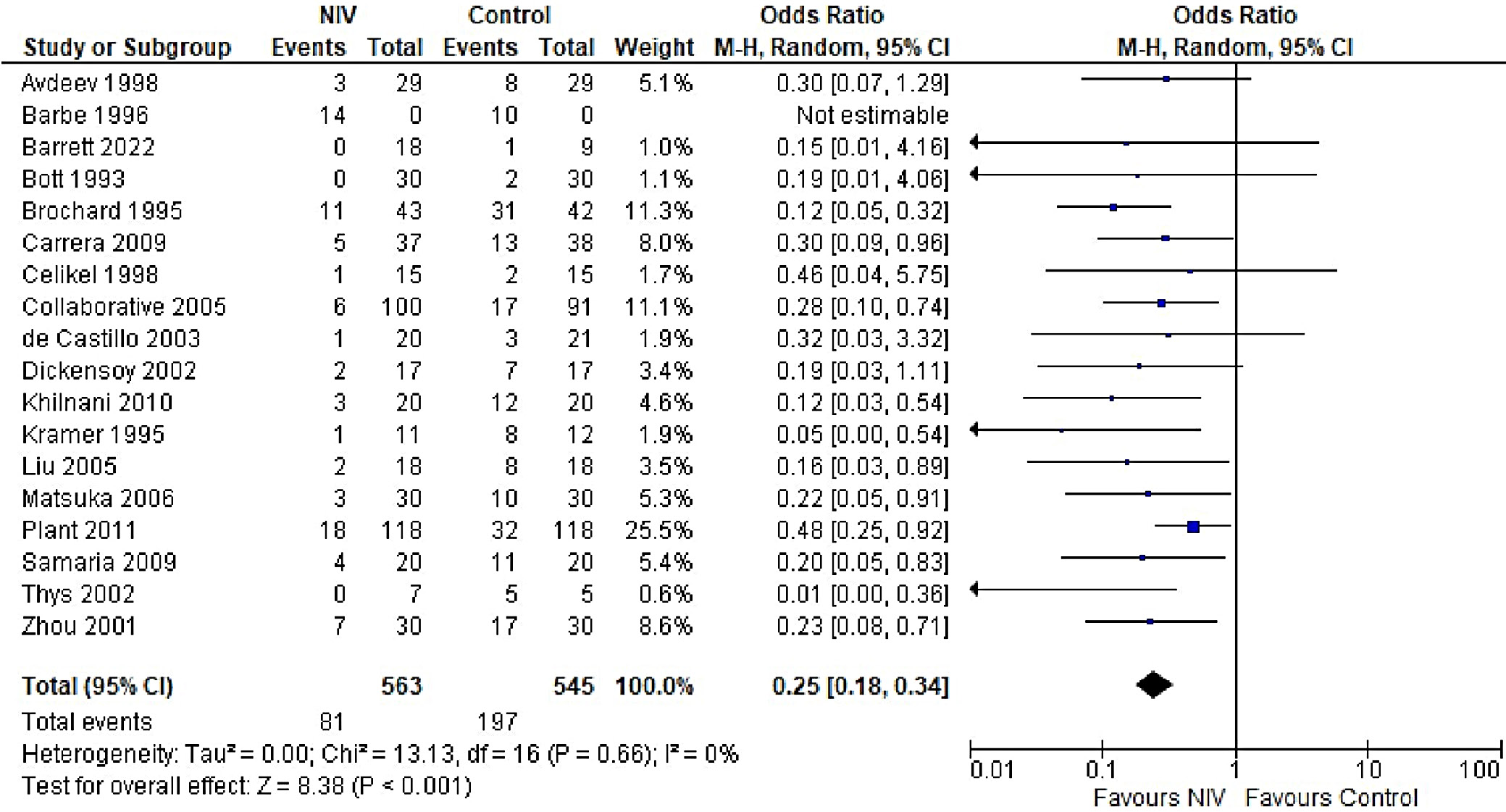

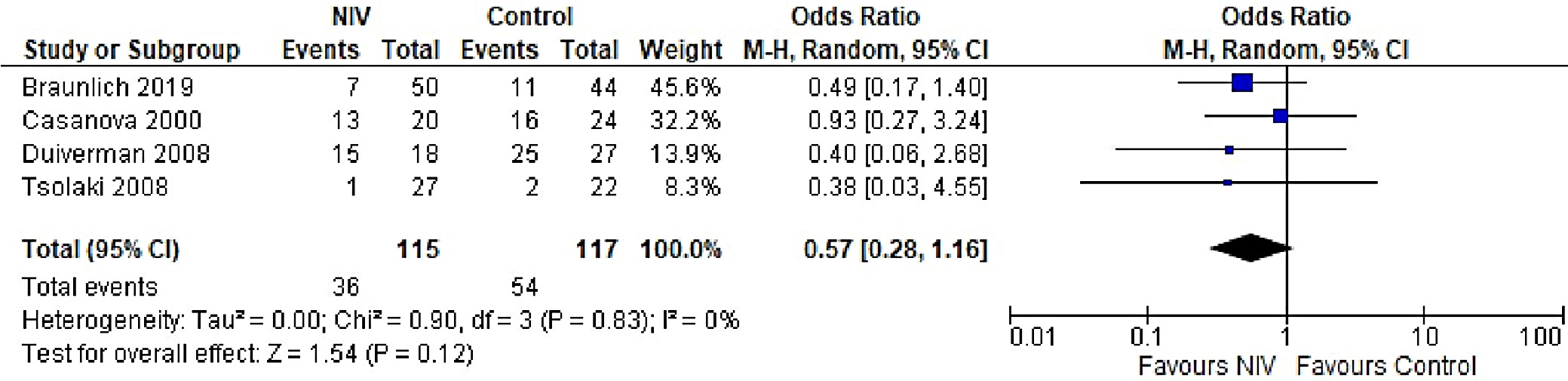

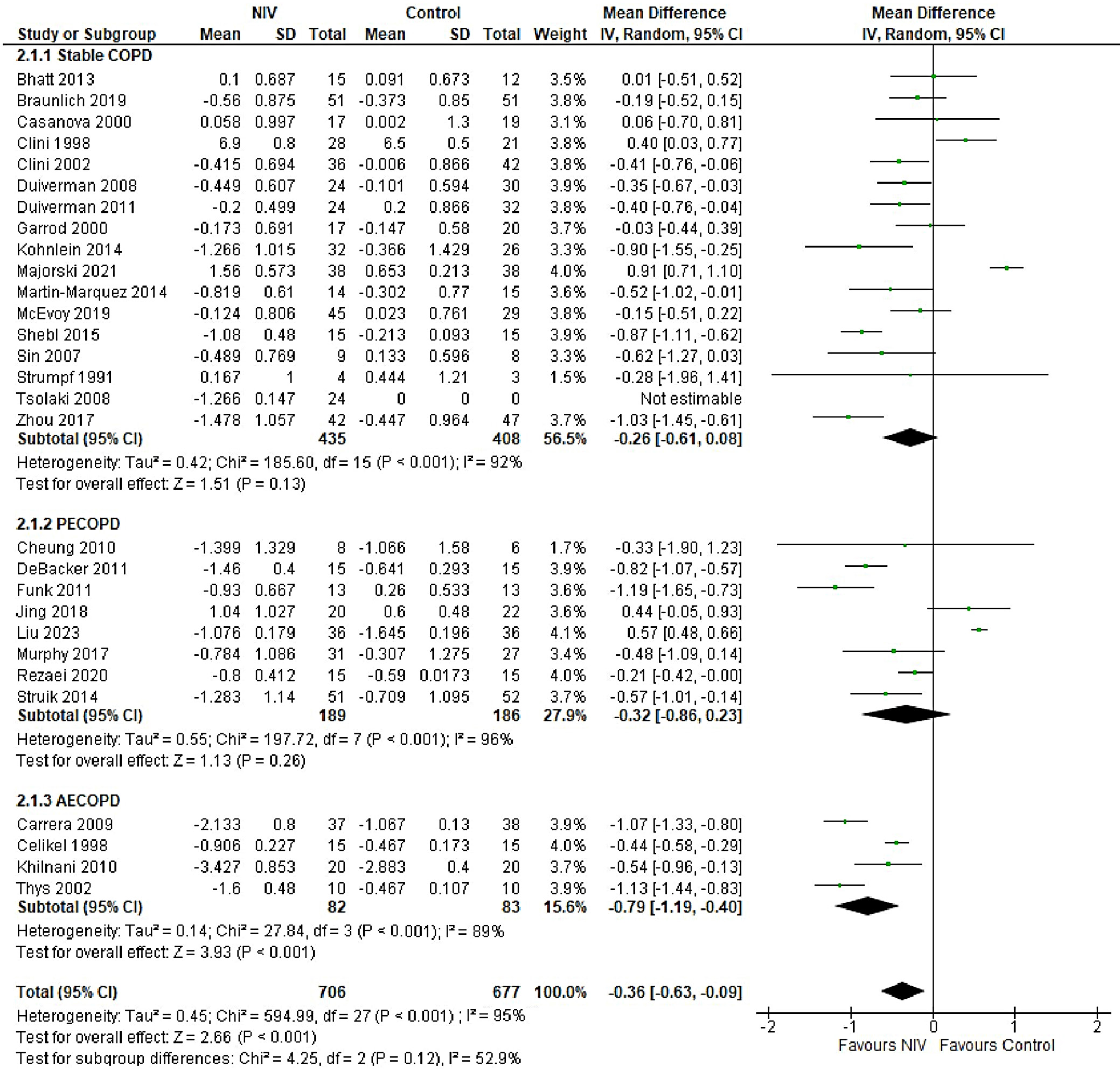

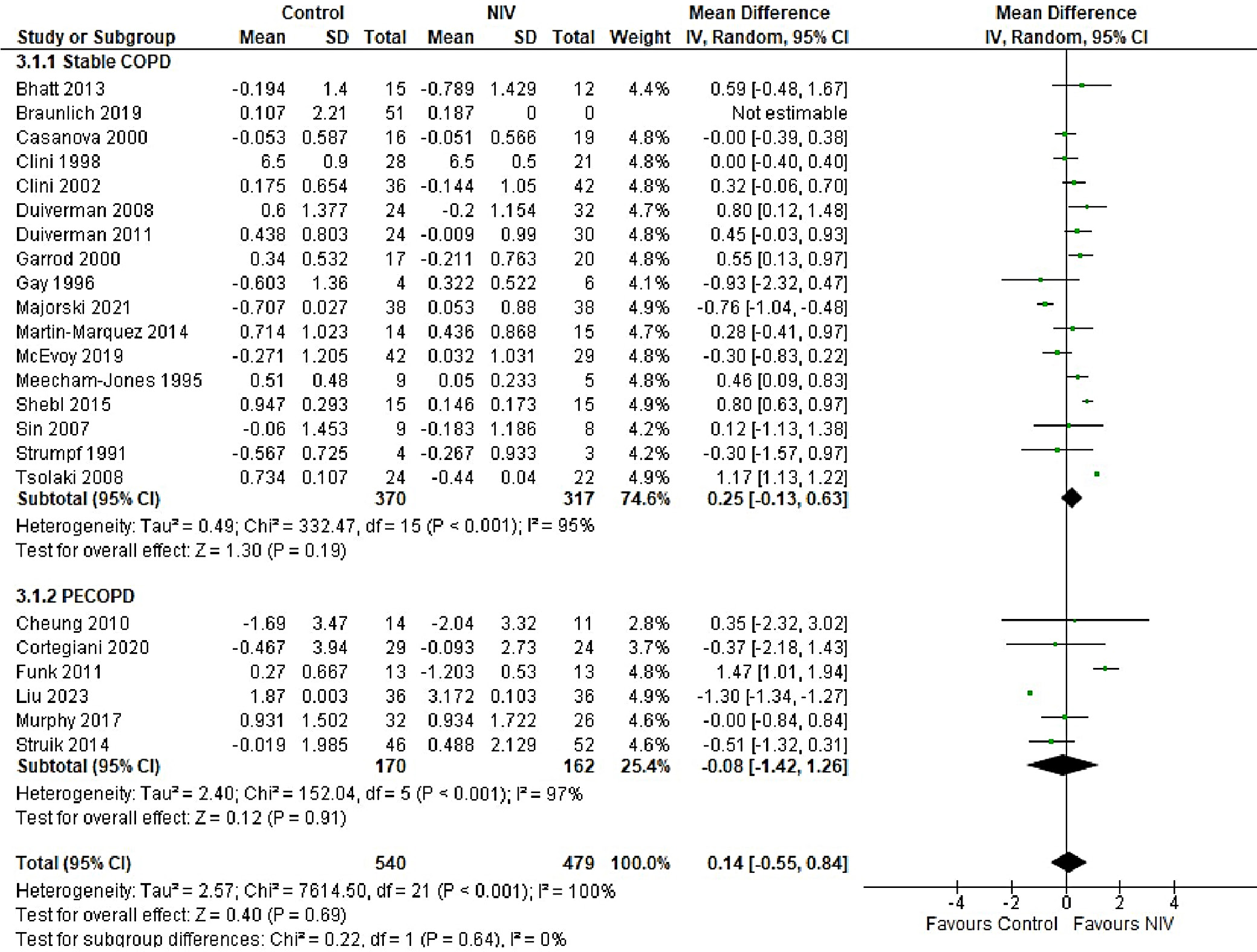

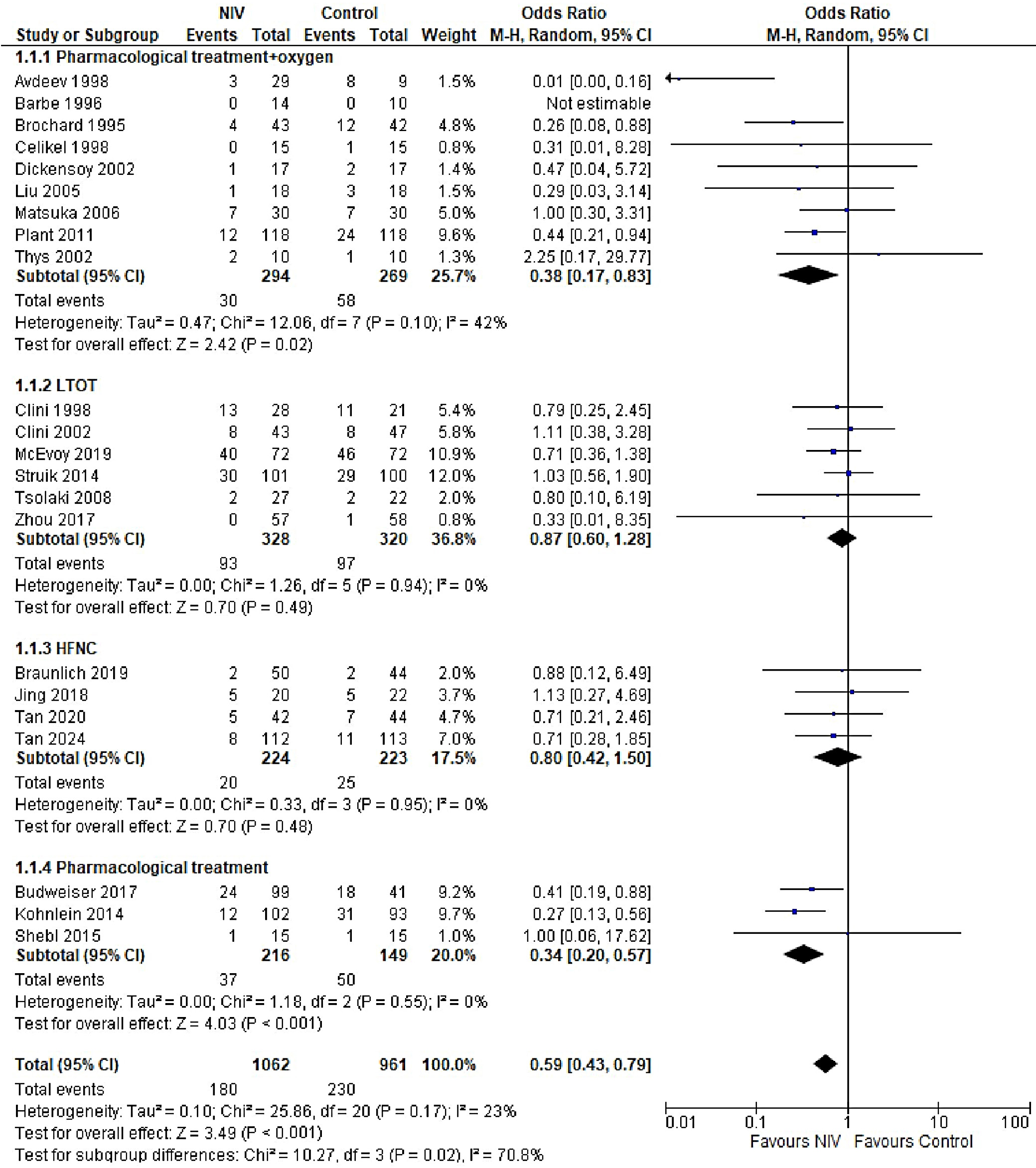

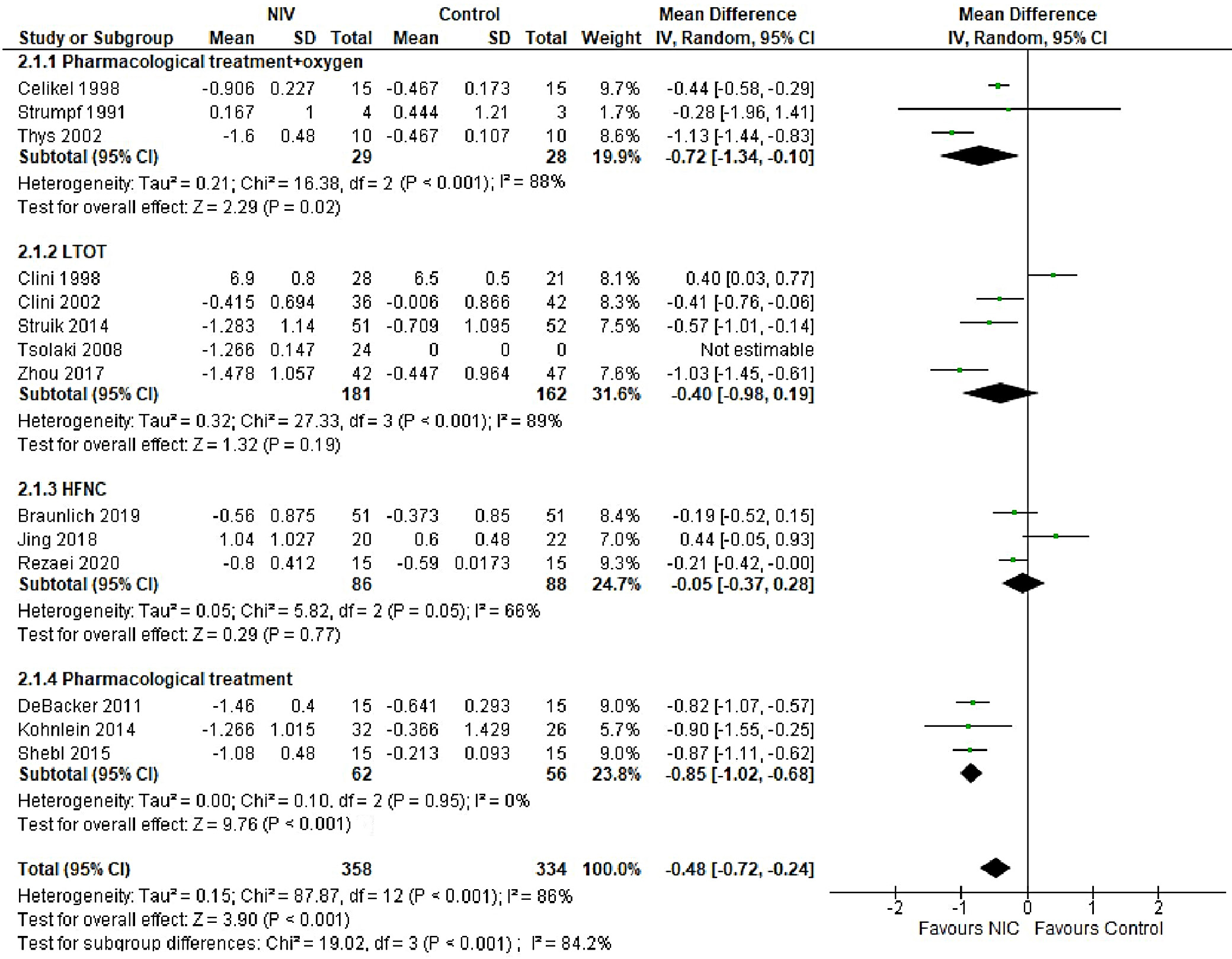

In patients with AECOPD, NIV significantly reduced the risk of intubation compared to the control group (OR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.18–0.34, p < 0.001). This analysis, based on 18 trials, showed no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), suggesting consistency in patient characteristics and study conditions (Figure 5). The funnel plot appeared symmetrical, and Egger’s test confirmed a low risk of publication bias (p = 0.173) (Supplementary Fig. 2). In patients with stable COPD, the exacerbation rate did not differ significantly between the NIV and control groups (OR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.28–1.16, p = 0.83), based on data from 4 studies. The low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) likely reflects similar patient profiles and consistent definitions of stable COPD (i.e., no exacerbations within the last 4 weeks). One trial27 (Casanova et al.) showed a nonsignificant result, possibly due to a slightly different definition of stability (no exacerbations in the past 3 months). The type of control intervention did not influence the direction of the results (Figure 6). The funnel plot suggested a low risk of publication bias (Supplementary Fig. 3). Continuous outcomes, such as PaCO2 and PaO2 levels, were analyzed across COPD subgroups, reported as changes in arterial blood gases from baseline to follow-up. Noninvasive ventilation was associated with a significantly greater reduction in PaCO2 levels compared to the control group (MD = –0.36, 95% CI: –0.63 to –0.09; p < 0.001), although high heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 95%). When stratified by COPD subgroup, trials involving Acute exacerbation chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) patients demonstrated a significant reduction in PaCO2 with NIV (MD = –0.79, 95% CI: –1.19 to –0.40; p < 0.001; I2 = 89%), while trials in stable COPD and PECOPD populations did not show statistically significant benefits. The high heterogeneity likely reflects variations in patient characteristics, control interventions and follow-up durations (ranging from 3 to 12 months) (Figure 7). The funnel plot appeared symmetrical, suggesting a low risk of publication bias, which was supported by Egger’s test for the stable COPD subgroup (p = 0.119) (Supplementary Fig. 4). No significant difference in PaO2 levels was observed between the NIV and control groups in trials involving stable COPD and PECOPD patients (MD = 0.14, 95% CI: –0.55 to 0.84; p = 0.69) (Figure 8). High heterogeneity (I2 = 100%) was likely attributable to differences in patient characteristics, ventilator settings, comparator treatments, and follow-up durations. The subgroup analysis did not reveal a statistically significant difference (p = 0.64). The funnel plot appeared symmetrical (Supplementary Fig. 5), indicating a low risk of publication bias, which was confirmed by Egger’s test for the stable COPD subgroup (p = 0.159). Subgroup analyses based on the type of control treatment revealed a significant reduction in mortality when the comparator was pharmacological therapy combined with oxygen supplementation (OR = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.17−0.83; p = 0.02; I2 = 42%) or pharmacological therapy alone (OR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.20−0.57; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%) (Figure 9). However, no significant reduction in mortality was observed when NIV was compared with LTOT or HFNC. The funnel plot for control-treatment subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 6) displayed high symmetry, suggesting a low likelihood of publication bias. Similar effects were observed for PaCO2 levels (Figure 10), with a significant reduction associated with NIV compared to pharmacological treatment combined with oxygen (MD = −0.72, 95% CI: −1.34 to −0.10, p = 0.02, I2 = 88%) and pharmacological treatment alone (MD = −0.85, 95% CI: −1.02 to −0.68, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%). The funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. 7) displayed a high degree of symmetry across various control treatments, indicating a low risk of publication bias.

Discussion

This paper provides an updated synthesis of the evidence for using NIV instead of usual care to manage different stages of COPD. Important outcomes such as mortality, exacerbations, intubation, and arterial gas levels (e.g. PaCO2 and PaO2 were assessed to determine the long- and short-term effects of NIV on patients at different stages of COPD. The findings of this study emphasize the importance of NIV in reducing mortality and morbidity, as well as the incidence of adverse events such as exacerbations and intubations, in COPD patients. Although several trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated the beneficial effects of NIV on survival, hospital admissions and length of stay, as well as improving quality of life, there are challenges associated with NIV devices that limit their applicability. These include mask leaks, difficulty wearing the device, mask discomfort, and severe hypoxia. Therefore, it is necessary to understand which patient baseline characteristics are most likely to benefit from NIV, the ideal length of treatment and continuous monitoring protocols, and training on the appropriate use of devices and ventilator settings.

The risk of bias assessment using the Cochrane tool revealed high performance and detection biases. Blinding of personnel and participants was not possible, as NIV devices and interfaces differ from usual care. Such treatments as pharmacological interventions and sham treatments may not always be feasible. This introduces an inherent bias when subjective outcomes such as quality of life and symptom assessment are measured. Therefore, this study only included objective measurements such as mortality, intubation and exacerbation rates, and arterial blood gases, which are not subject to bias and provide more reliable results regarding the efficacy of NIV. Our study showed that NIV use across different COPD stages decreases mortality. However, there was no significant difference in mortality outcomes between PECOPD patients receiving NIV or usual care.

The effect of NIV on COPD varies between patients with stable COPD and those with PECOPD. Some meta-analyses have reported nonsignificant differences in mortality outcomes among patients with stable COPD and PECOPD. However, other studies, including our analysis, have demonstrated a mortality benefit in patients with stable COPD.14, 70 This benefit may be attributed to persistent hypercapnia commonly observed in stable COPD patients, in contrast to PECOPD patients, where hypercapnia may be transient and often accompanied by additional complications. In patients with AECOPD, NIV was found to significantly reduce mortality rates, which could be linked to a reduced need for intubation – thus minimizing the risk of prolonged hospital and ICU stays and associated infections. The exacerbation rate among patients with stable COPD was significantly lower with NIV compared to usual care. Although this analysis included only a limited number of studies (n = 4), it provides preliminary evidence that long-term or chronic use of NIV may help reduce exacerbation frequency in COPD patients. A greater reduction in PaCO2 levels in stable COPD patients likely contributes to improved alveolar ventilation and respiratory muscle function, particularly in cases of chronic hypercapnia, which may predispose patients to fewer exacerbations. Consistent with previous meta-analyses and the GOLD report, our findings demonstrated a significant improvement in PaCO2 levels in all patients receiving NIV compared to usual care. However, no significant improvement was observed in PaO2 levels between the 2 groups. The beneficial effect of NIV in lowering PaCO2 is attributed to enhanced alveolar ventilation, increased tidal volume and reduced respiratory muscle fatigue as a result of the positive airway pressure delivered by NIV devices, which facilitates more effective CO2 elimination.2, 11, 71 However, destruction of alveolar units and underlying lung pathology can impair oxygen diffusion into the bloodstream, thereby limiting the impact of NIV on arterial oxygenation and often necessitating supplemental oxygen. Moreover, because several studies included oxygen supplementation or LTOT in the standard treatment arms, the differences in PaO2 levels between NIV and comparator groups were often attenuated, rendering the effect of NIV on oxygenation statistically nonsignificant. Subgroup analyses revealed that NIV significantly reduced both mortality and PaCO2 levels when compared to pharmacological or standard oxygen therapy. In contrast, differences were nonsignificant when compared to LTOT and HFNC therapy. These findings may be attributed to the superior ventilatory support provided by NIV, which enhances alveolar ventilation and facilitates CO2 clearance – mechanisms not fully addressed by oxygen or pharmacologic therapy alone. Notably, HFNC delivers heated and humidified oxygen while also generating low-level positive airway pressure, promoting CO2 washout, which may explain its comparable or potentially superior efficacy to NIV in certain clinical scenarios.

Limitations

Despite our study proving a comprehensive and current review and quantitative evidence on the use of NIV in COPD patients in different stages, it has certain limitations that require consideration when generalizing these results. The high heterogeneity present in the results of this analysis, particularly for arterial blood gas levels, PaCO2 and PaO2 is related to heterogenous patient populations and baseline demographics. Differences in baseline PaCO2 levels, comorbidities, and severity of COPD can affect the magnitude of effect of NIV, thereby affecting the efficacy of NIV. Other factors, such as ventilator pressure settings and duration of application, concomitant treatments, comparators such as supplemental oxygen treatment, variable lengths of follow-up between different studies, also result in heterogeneity. However, analyzing studies with homogenous populations regarding patient characteristics results in a limited number of studies included in each subgroup, underpowering the study. Differences in the definitions of outcomes, such as exacerbation, which are often not specified in the trials, also makes combining of results challenging. The numbers of exacerbations and intubations have not been reported for most studies prior to the use of NIV. This lack of information makes it difficult to determine the effectiveness of NIV in decreasing the frequency of attacks. As discussed above, the high risk of detection bias makes it necessary to interpret the results with caution as they may not be generalizable in larger patient populations and the efficacy of NIV can be overestimated without blinding. To provide more robust evidence on the use of NIV, it is important to identify patient subgroups, such as those with hypercapnic respiratory failure, certain comorbidities, and stages of COPD, that are most likely to benefit from NIV use. Additionally, since the efficacy of NIV depends upon its correct use and adherence particularly in case of long-term use, trained personnel are required to administer it, and patients and their caregivers should be educated on the proper use of masks to maximize the benefits offered by NIV.

Since NIV devices demonstrated particular benefit in AECOPD patients by reducing mortality, intubation rates and PaCO2 levels, their integration into clinical practice appears most justified in this subgroup. Moreover, the inconsistent effects of NIV on PaO2 and PaCO2 levels suggest that NIV may not be the optimal ventilation strategy when oxygenation is the primary therapeutic goal. Instead, its use should be focused on improving alveolar ventilation and respiratory muscle function. Understanding the differential effects of NIV across COPD stages may assist clinicians in selecting appropriate candidates who are most likely to derive significant benefit from this intervention.

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis, we demonstrated that NIV devices reduce mortality, exacerbation frequency and intubation rates in patients across different stages of COPD, including stable COPD, PECOPD and AECOPD. The impact of NIV on gas exchange was variable: NIV significantly reduced PaCO2 levels, but the improvement in PaO2 was not statistically significant. The efficacy of NIV also varied depending on the COPD stage, with the greatest benefit observed in patients with AECOPD. The high heterogeneity among studies likely reflects differences in patient populations, baseline characteristics, NIV settings, and duration of use. These findings highlight the need to individualize NIV therapy based on patient-specific factors to optimize clinical outcomes.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17072868. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. Funnel plot for mortality outcome a) in stable COPD patients b) in PECOPD patients and c) in AECOPD.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Funnel plot for intubation in AECOPD patients.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Funnel plot for exacerbation in stable COPD patients.

Supplementary Fig. 4. Funnel plot for PaCO2 levels a) in stable COPD patients b) in PECOPD patients and c) in AECOPD.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Funnel plot for PaO2 level a) in stable COPD patients b) in PECOPD patients.

Supplementary Fig. 6. Funnel plot for mortality in intervention group stratified by type of control treatment.

Supplementary Fig. 7. Funnel plot for PaCO2 levels in intervention group stratified by type of control treatment.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.