Abstract

Background. Acute cholecystitis (AC) is a common biliary disorder, most often caused by gallstones obstructing the cystic duct and leading to gallbladder inflammation.

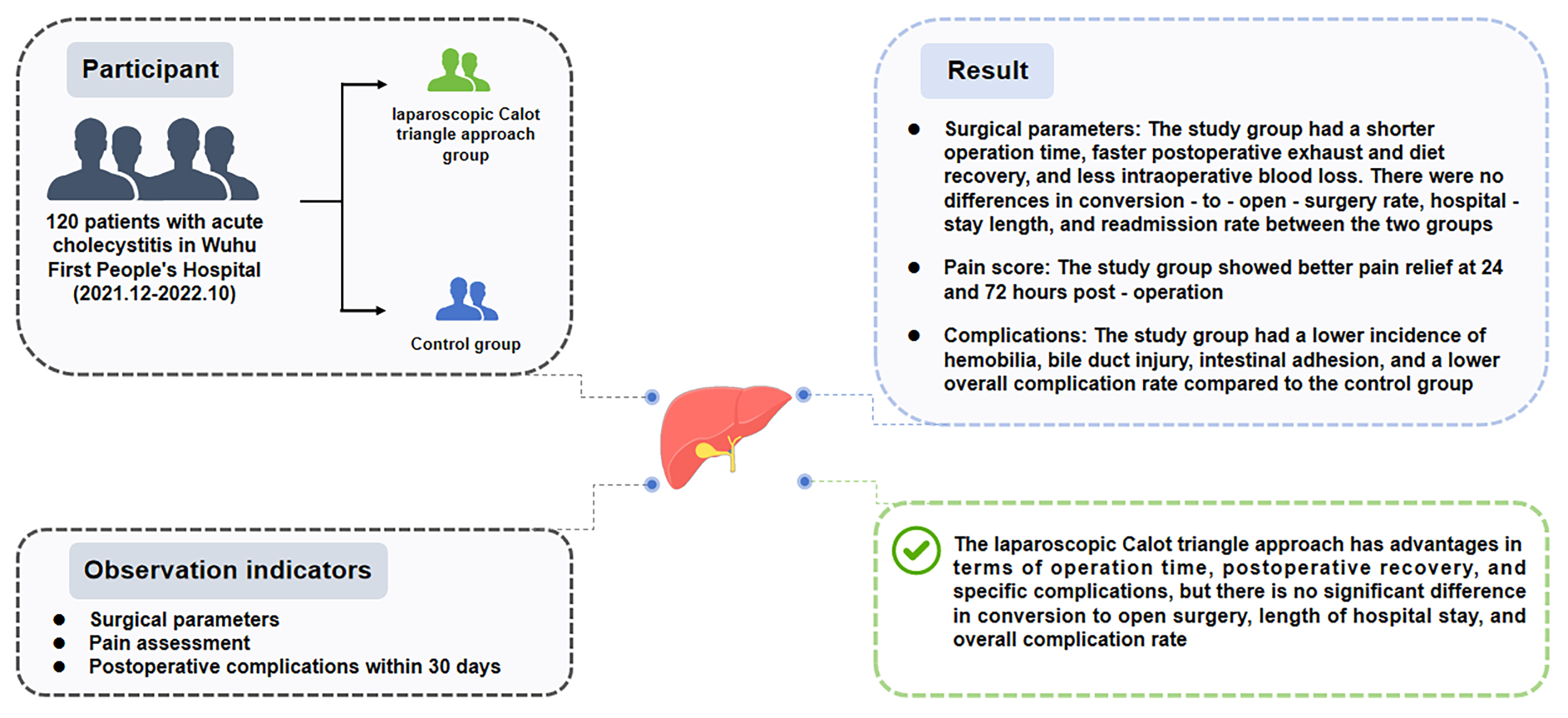

Objectives. This study aimed to compare the therapeutic efficacy and complication rates of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) performed using the Calot’s triangle approach vs traditional LC techniques in the treatment of AC.

Materials and methods. A retrospective analysis was conducted on 120 patients diagnosed with AC, with 60 patients undergoing LC using the Calot’s triangle approach (study group) and 60 patients treated with traditional LC techniques (control group). Surgical parameters, including operation time, intraoperative hemorrhage, postoperative recovery times, and 30-day postoperative complications were recorded. Intraoperative adhesion formation was evaluated through direct visualization and graded based on severity. Postoperative pain was assessed using the visual analogue scale (VAS).

Results. There was no statistically significant difference in the baseline characteristics between the 2 groups, confirming their comparability. The study group (Calot’s triangle approach) demonstrated significantly shorter average operation time, postoperative exhaust time, and diet recovery time compared to the control group. Additionally, patients in the study group had significantly lower intraoperative bleeding, lower VAS pain scores at 24 h and 72 h postoperatively, and a lower overall complication rate compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

Conclusions. The LC Calot’s triangle approach demonstrated shorter operation times and lower rates of certain complications compared with traditional LC techniques. However, the absence of statistically significant differences in some key outcomes highlights the need for further research to fully evaluate its clinical advantages and long-term benefits.

Key words: laparoscopic cholecystectomy, acute cholecystitis, Calot’s triangle approach

Background

Acute cholecystitis (AC) is a common biliary disorder that typically results from obstruction or inflammation of the gallbladder caused by gallstones.1 Patients commonly present with severe upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Without prompt intervention, AC may lead to serious complications, such as gallbladder perforation, abscess formation, or even pancreatitis.2 Therefore, timely and effective treatment is essential for preserving the health and preventing disease progression in patients with AC.

Laparoscopic surgery is a minimally invasive surgical technique performed through small incisions located in the abdomen. Compared with traditional open surgery, laparoscopic surgery offers several advantages, including reduced tissue trauma, faster postoperative recovery, and fewer complications.3 Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has been widely recognized as the standard treatment for AC. However, the selection of an appropriate surgical approach is critical to the success of the surgical procedure and the recovery of patients. Various surgical techniques are available for LC, including the conventional approach and the Calot-based approach (termed as Calot-guided LC in our present study).4, 5 Conventional LC techniques generally include the 4-port,6, 3-port7 and transumbilical single-port approaches.8

A comprehensive review of the literature on the efficacy and complications associated with the Calot-guided LC compared to conventional LC techniques, particularly in the context of AC, reveals distinct advantages and disadvantages for each method. Calot-guided LC enhances visualization of the cystic duct and artery, thereby reducing the risk of bile duct injuries.9 Additionally, this approach decreases the need for conversion to open surgery by enabling more accurate anatomical identification and facilitating early recognition of anatomical variations that are crucial in preventing complications.10 In contrast, conventional LC techniques benefit from greater familiarity and extensive clinical experience among surgeons, which may contribute to lower complication rates and shorter operative times, as they typically require less meticulous dissection compared with the Calot-guided approach.10 However, despite improved visualization, Calot’s triangle-guided LC still carries a risk of bile duct injuries, particularly in cases with significant inflammation or fibrosis, and may be associated with higher postoperative complication rates, such as bile leakage and infection, due to the complexity of the dissection.10

Conventional LC techniques also present a notable risk of bile duct injury and may result in a higher likelihood of conversion to open surgery when anatomical structures are difficult to identify.10 Notably, early LC (ELC) is generally recognized as the optimal treatment for AC, with Calot-guided LC offering particular advantages in this setting due to its superior anatomical identification and reduced risk of bile duct injuries.10, 11 Moreover, performing ELC within 24 h of presentation is associated with lower complication rates compared to delayed surgery.11 Overall, the surgeon’s experience should guide the selection of surgical approach, the patient’s condition, and the presence of inflammation or anatomical anomalies. Nonetheless, ELC remains the preferred treatment for AC, and the Calot-guided method may provide better intraoperative visualization and potentially fewer complications.

The LC Calot’s triangle approach is a relatively new approach for LC, which emphasizes the delicate dissection and protection of the LC Calot’s triangle structure to reduce complications such as common bile duct injury and thereby enhance surgical safety and success rates.12 However, most of the current clinical studies have focused on the clinical outcomes of different Calot-based approaches or the comparison of outcomes between previous conventional LC techniques (such as the 3-port approach and 4-port approach). Fewer studies have been conducted on the comparison of conventional LC techniques and the Calot-guided LC.

Objectives

This study aimed to compare the efficacy and complication rate of conventional LC techniques and the Calot’s triangle approach in the treatment of AC, with the goal of maximizing surgical success rates and improving postoperative recovery outcomes.

Materials and methods

General information

A single-center retrospective study protocol was conducted, enrolling patients diagnosed with AC who underwent elective cholecystectomy at the First People’s Hospital of Wuhu (China) between December 2021 and October 2022. Patients were assigned to 2 groups. The study group was treated using a Calot-guided LC technique, which emphasized precise dissection within the anatomical landmarks of Calot’s triangle to minimize the risk of injury to vital structures. The control group underwent conventional LC, which involved broader anatomical exposure without the targeted precision of the Calot-based technique. Group allocation was determined based on factors such as anatomical complexity and disease severity, allowing surgeons to select the most appropriate technique for each patient to optimize operative safety and outcomes. In this study, the Calot-based approach was defined as a laparoscopic technique focused on the precise identification and dissection of the anatomical structures within LC Calot’s triangle, namely the cystic duct, cystic artery and common bile duct, to minimize the risk of injuries and complications during LC. In contrast, conventional LC included established methods such as the 3-port and 4-port techniques, which prioritized general exposure of the gallbladder and adjacent tissues without specific attention to detailed anatomical structures.

Based on a literature review, the postoperative visual analogue scale (VAS) score in the control group was 3.32 ±0.59, and it was expected to decrease by 1.22 in the study group; both of them had a similar standard deviation (SD). Additionally, α = 0.05 (two-sided) and 90% power were set. According to the formula for calculating sample size [N = (Zα/2 + Zβ)2 × (p1(1–p1) + p2(1–p2))/δ2], the sample size was calculated to be 90 cases. To account for a projected 15% loss to follow-up, a total of 120 patients were enrolled, with 60 in each group.

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the First People’s Hospital of Wuhu (approval No. YYLL20230051), and patient privacy was strictly maintained to ensure data confidentiality and security. Prior informed consent was obtained from all participating patients and their families. The research team collected relevant clinical and laboratory data from all patients while ensuring the anonymization and confidentiality of all included cases. Data collection encompassed a range of parameters, including sex, age, disease duration, family history, comorbidities, gallbladder wall thickness, type of disease (simple, gangrenous, or suppurative), and routine blood parameters.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Cases were selected for inclusion based on the following criteria: 1) Patients with physical examination findings and imaging results that fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for AC, including those with acute attacks of chronic cholecystitis13; 2) Patients who required surgical intervention and met the clinical indications for LC following a thorough clinical evaluation14; 3) Only those with complete clinical data were considered for inclusion to ensure comprehensive analysis and reporting.14

Patients were excluded from the study based on the following criteria: 1) Patients who developed serious complications, such as gallbladder perforation, abscess formation or pancreatitis; 2) Patients with a history of open surgery that might have impacted the surgical approach or outcomes; 3) Patients with significant comorbidities, including severe cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, malignant tumors, or immune system disorders; 4) Patients deemed suitable for LC but were intolerant to anesthesia; 5) Patients with a history of mental disorders or those who demonstrated poor compliance; 6) Patients with incomplete or insufficient clinical information that hindered a definitive diagnosis of AC or those deemed inappropriate for enrollment by other research teams.

Surgical techniques

Study group (LC Calot’s triangle approach)

For the Calot-guided LC approach, 1 key criterion was the anatomical consideration, which included the presence of clear visualization of the Calot’s triangle. This technique was typically favored in patients with identifiable anatomical landmarks in this region, allowing for safe dissection. Additionally, patients were required to have minimal or no prior surgical history that could lead to significant adhesions around the gallbladder or surrounding structures. The type and severity of AC also influenced the selection process. Patients presenting with uncomplicated AC, where the risk of biliary injury was lower, were often considered ideal candidates.

In the study group, LC was performed using the Calot’s triangle approach, which focused on the precise identification and dissection of the anatomical structures within the Calot’s triangle, specifically the cystic duct, cystic artery and common bile duct, to minimize the risk of injury to vital structures and reduce the incidence of intraoperative complications. Briefly, patients were placed in the supine position and underwent general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. After routine disinfection and surgical draping, the surgical field was fully exposed. A 1-cm transverse incision was made at the lower edge of the umbilicus, and a pneumoperitoneum needle was inserted to establish pneumoperitoneum via CO2 insufflation, with abdominal pressure maintained at 12–14 mm Hg (1 mm Hg = 0.133 kPa). The pneumoperitoneum needle was then removed, and a 10 mm trocar was inserted for the laparoscope.

A second 1-cm transverse incision was created 1 cm below the xiphoid process to insert a 10-mm trocar, through which an electrocautery hook was introduced. Additionally, a 5-mm incision was made along the midclavicular line, 1 cm below the costal margin, and a 5-mm trocar was inserted to serve as the operation hole for a grasper. If severe adhesions were encountered, a 5-mm incision was established at the right anterior axillary line to function as a 4th port. Under laparoscopic visualization, the size of the gallbladder and its relationship with surrounding tissues were assessed. Adhesions were separated using a suction device, and Calot’s triangle, along with the porta hepatis, were carefully dissected.

The serous layer of Calot’s triangle was opened, followed by meticulous dissection of the cystic artery first, and then the cystic duct was identified. Once the anatomical relationship among the cystic artery, cystic duct, common bile duct, and common hepatic duct was confirmed, the cystic artery was prioritized for transection. After secondary confirmation of both the cystic artery and cystic duct, the cystic duct was subsequently clipped and transected. The gallbladder was excised and removed through the incision below the xiphoid process. Upon completion of the procedure, CO2 was released from the abdominal cavity, and all incisions were closed with routine suturing techniques. The emphasis on precise dissection and preservation of anatomical structures within Calot’s triangle differentiates this approach from more generalized dissection techniques.

Control group (conventional LC techniques)

The conventional LC techniques were selected based on specific clinical criteria. Anatomical challenges were a key consideration; for example, patients with a history of prior abdominal surgery or significant intra-abdominal scarring were more likely to require traditional approaches that provide broader surgical exposure. Additionally, patients suffering from severe or complicated AC, such as those with perforation or abscess formation, often necessitated the generalized exposure provided by traditional methods.

In the control group, LC was performed using conventional LC techniques, including both the 3-port and 4-port techniques. Unlike the LC Calot’s triangle approach, these conventional LC techniques prioritized general exposure of the gallbladder and surrounding tissues without a specific focus on the precise dissection of Calot’s triangle structures. The patients were positioned supine, and general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation was administered. Once a satisfactory level of muscle relaxation was achieved, an artificial pneumoperitoneum was established using the subumbilical closed technique, with an abdominal pressure maintained between 1.3 kPa and 2.0 kPa. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was conducted through either the 3-port or 4-port approach, depending on the surgeon’s assessment of the case. For the 3-port approach, a 10-mm trocar was inserted at the lower margin of the umbilicus for the laparoscope, while 2 additional 5-mm ports were placed – 1 below the xiphoid process and the other at the intersection of the right midclavicular line and the costal margin. For the 4-port approach, an additional 5-mm port was inserted 5 mm below the right anterior axillary line to assist in cases of severe adhesions.

During the procedure, the gallbladder was elevated, and general dissection was performed to expose the cystic duct and cystic artery. These structures were subsequently clipped and transected with Hem-o-lok clips. The gallbladder was then detached from the liver bed and retrieved through the umbilical incision. Hemostasis was secured, and routine subhepatic drainage was performed when indicated. Although conventional LC techniques also required identification of the cystic duct and cystic artery, they did not prioritize the same degree of precision in the dissection and preservation of Calot’s triangle structures as was applied in the study group.

Observation indicators

Both groups received identical pre- and postoperative care. The following parameters were recorded for com- parative analysis: operation time, intraoperative hemor- rhage, conversion to open cholecystectomy, time to first postoperative flatus, time to diet resumption, postopera- tive length of stay, and 30-day postoperative complications.

Pain was evaluated using the VAS, where higher scores indicated more severe pain. The VAS scores were compared preoperatively and at 24 h and 72 h postoperatively.

The incidence of 30-day postoperative complications, including biliary leakage, hemobilia, bile duct injury, intestinal adhesion, and incision infection, was recorded.

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS v. 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The normality of continuous variables was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data that conformed to a normal distribution were expressed as mean ±SD, and differences between the 2 groups were analyzed using the independent samples Student’s t-test. Data that did not follow a normal distribution were presented as median with interquartile range (IQR; M (25%, 75%)), and differences between the 2 groups were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Differences among 3 or more related samples were analyzed using Friedman’s test for nonparametric repeated measures. Categorical data were reported as counts and percentages (n (%)) and statistically analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 test of independence with Yates’s continuity correction. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 to establish statistical significance.

Results

Comparison of baseline data

A total of 120 patients with AC were included in this study. All patients were randomly divided into 2 groups and underwent LC using either the Calot-guided LC technique or conventional LC techniques. Results from the Shapiro–Wilk test assessing the normality of continuous variables are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The baseline characteristics of both groups are presented in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found between groups in terms of sex, age, disease duration, family history, comorbidities, type of disease, gallbladder wall thickness, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, and platelet count (Pearson’s χ2 test/Mann–Whitney U test/independent samples Student’s t-test: p > 0.05), indicating comparability for subsequent analyses.

Comparison of surgery status

The surgical status of the 2 groups is shown in Table 2. The results of whether the continuous variables conformed to a normal distribution were shown in Supplementary Table 2. Compared with conventional LC, the Calot-guided technique was associated with significantly shorter operation time, reduced intraoperative blood loss and earlier postoperative recovery, including shorter times to first flatus and diet resumption (Mann–Whitney U test/independent samples Student’s t-test: p < 0.001). At the 30-day follow-up, the LC Calot’s triangle approach had 3 readmissions (5.0%, 3/60), whereas the conventional LC techniques had 6 (10.0%, 6/60). There were no significant differences in readmission rates (Pearson’s χ2 test of independence with Yates’s continuity correction: p = 0.488), conversion to open cholecystectomy (Pearson’s χ2 test of independence with Yates’s continuity correction: p > 0.999), and postoperative length of stay (Mann–Whitney U test: p = 0.351) between the groups. Overall, the Calot-guided LC demonstrated improved surgical outcomes, including reduced operation times and postoperative recovery metrics, without significant differences in readmission rates or conversion to open surgery compared to the conventional LC techniques.

Comparison of pain scores before and after surgery

Pre- and postoperative pains were evaluated using the VAS, with higher scores indicating more severe pain. Normality analysis revealed that pre- and postoperative VAS scores in both groups were non-normally distributed (Supplementary Table 3). Therefore, the Friedman test was employed for statistical analysis. Patients in the study group experienced significantly greater pain relief at both 24 h and 72 h postoperatively (degrees of freedom (df) = 2, Z = 187.995, p < 0.001) (Table 3), suggesting improved postoperative pain control in this group.

Comparison of postoperative complications

The incidence of biliary leakage and incision infection was slightly lower in the Calot-based approach (1 case and 2 cases, respectively) than in the conventional LC techniques (2 cases and 3 cases, respectively), although this difference was not statistically significant (Pearson’s χ2 test of independence with Yates’s continuity correction: df = 1, p > 0.999). In contrast, subjects receiving Calot-guided LC exhibited a significantly lower incidence of hemobilia (0% vs 11.7%, Pearson’s χ2 test of independence with Yates’s continuity correction: df = 1, p = 0.019), bile duct injury (1.7% vs 15%, Pearson’s χ2 test of independence with Yates’s continuity correction: df = 1, p = 0.008) and intestinal adhesion (0% vs 10%, Pearson’s χ2 test of independence with Yates’s continuity correction: df = 1, p = 0.036). The complication rate was significantly lower in the study group (6.7%) compared to the conventional LC group (26.7%) (Pearson’s χ2 test of independence with Yates’s continuity correction: df = 1, p = 0.003) (Table 4). These findings suggested that the LC Calot’s triangle approach may reduce the risk of postoperative complications, underscoring its potential advantages in terms of surgical safety and clinical efficacy.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that, compared with conventional LC techniques, the Calot-guided approach significantly improved key surgical outcomes, including shorter operative time, faster postoperative recovery duration, and a reduced incidence of specific complications such as bile duct injuries and hemobilia. Although no statistically significant differences were found in postoperative hospital stay or conversion rates to open surgery, these findings indicated that Calot’s triangle approach might offer unique benefits in enhancing surgical safety and recovery for patients with AC. These benefits are especially evident in cases with minimal inflammation and clearly identifiable anatomical structures, highlighting the potential of Calot’s triangle approach in supporting individualized treatment choices in clinical practice.

Acute cholecystitis is a common cause of abdominal emergencies, with LC being the standard of care. While conventional LC techniques – including the 4-port, 3-port and single-port methods – have been widely adopted, each comes with its own set of limitations. For example, although the 3-port method reduces the number of incisions, it still requires multiple entries, which can increase postoperative discomfort and visible scarring.15, 16 In contrast, the Calot-guided LC emphasizes precise dissection within Calot’s triangle, facilitating safer identification of vital anatomical structures, including the cystic artery, common bile duct and common hepatic artery.17 Compared with conventional LC techniques, the Calot-guided LC emphasizes meticulous anatomical precision, potentially reducing intraoperative complications and improving patient outcomes.

Our findings align with previous research. Al-Rekabi et al.14 demonstrated that isolating and clipping the cystic artery outside Calot’s triangle minimized stapler-related injuries and improved bleeding control. Additionally, studies by Fateh et al. confirmed the benefits of Calot’s triangle approach in reducing risks such as bile duct injury due to its emphasis on precise anatomical dissection.18, 19 However, unlike previous studies, our findings showed no statistically significant differences in conversion rates to open surgery or postoperative length of stay. These discrepancies may stem from variations in patient characteristics or the surgeon’s level of experience. Furthermore, the Calot-guided approach may reduce the risk of gastrointestinal paralysis and bowel distension after surgery, thereby supporting faster restoration of intestinal function.20 In addition, the overall incidence of complications was significantly lower in the study group compared to the control group in this study. A surgical strategy using the LC Calot’s triangle approach emphasizes the fine dissection and protection of the structures surrounding the gallbladder, including the gallbladder artery and the common bile duct. As a result, the risk of postoperative complications such as bleeding and biliary leakage and consequent readmission can be reduced.21 Cholecystitis and surgical trauma can trigger inflammatory and immune responses. Compared with conventional techniques, the Calot-based strategy may minimize tissue injury and allow for more refined dissection, thus attenuating inflammation, edema and associated complications.22 Additionally, patients in the study group experienced significantly greater pain relief at both 24 h and 72 h after surgery, suggesting the advantages of the Calot-guided LC in postoperative pain management.

The lack of statistically significant differences in certain outcomes warrants further consideration. First, it is essential to determine whether the study was adequately powered to detect clinically meaningful differences, particularly in rare events such as conversion to open surgery. A post hoc power analysis based on the observed effect sizes could clarify whether the sample size was sufficient. Furthermore, while the benefits of the Calot-guided approach are evident in several aspects, its broader clinical impact should be interpreted in the context of existing literature and variability in practice. Comparison with previous studies evaluating alternative surgical techniques may offer valuable insights into the relative efficacy and safety of the Calot-guided LC approach, thereby supporting evidence-based clinical decision-making. Additionally, the challenges in patient selection and surgical execution inherent to each method might influence outcomes and warrant further exploration in future research.

Limitations

While our study aimed to demonstrate differences between Calot’s triangle approach and conventional LC techniques in treating AC, it is essential to evaluate whether the study had sufficient statistical power to detect these differences across all measured outcomes. The initial sample size calculation was based on anticipated differences in postoperative pain scores between the 2 groups. However, for secondary outcomes such as conversion rates to open surgery and incidence of specific complications, the sample size may have been insufficient to identify smaller yet clinically significant effects. Conducting a post hoc power analysis could elucidate the potential limitations related to statistical power. Moreover, future studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to validate the observed trends with greater confidence. In addition, this study is subject to several inherent limitations, including its single-center setting, retrospective design, and lack of stratification based on surgeon experience. To comprehensively assess the relative efficacy and safety of these surgical approaches, future research should employ multicenter, prospective designs with standardized assessments of operator proficiency.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that the LC Calot’s triangle approach may provide significant benefits over conventional LC techniques, particularly in reducing operation time, expediting postoperative recovery, and minimizing specific complications like bile duct injuries and hemobilia. However, no statistically significant differences were observed in the conversion to open surgery, length of hospital stay or overall complication rates. These findings suggest that while the Calot-guided LC has distinct advantages, its broader clinical impact may vary based on surgeon experience and patient selection criteria. Further multicenter, prospective studies are needed to fully validate these findings and better assess the role of Calot’s triangle approach in managing AC.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15381600. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. The results of the normality test of baseline data.

Supplementary Table 2. The results of the normality test of surgery status.

Supplementary Table 3. The results of the normality test of pain scores.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.