Abstract

Background. The precise causal relationship between circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis has not yet been fully elucidated.

Objectives. To identify biomarkers that enable earlier and more accurate diagnosis of sepsis.

Materials and methods. The causal relationships between 41 circulating inflammatory factors, C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin (PCT) with sepsis and 28-day sepsis-related mortality were evaluated using two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses.

Results. This study revealed negative causal associations between genetically predicted circulating inflammatory factors–interleukin-6 (IL-6) (odds ratio [OR] = 0.923; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.854–0.998; p = 0.044), RANTES (OR = 0.926; 95% CI, 0.862–0.994; p = 0.033), and macrophage inflammatory protein-1β (MIP1β) (OR = 0.957; 95% CI, 0.919–0.996; p = 0.032) – and the risk of sepsis. Furthermore, positive causal relationships were observed between CRP and sepsis (OR = 1.140; 95% CI: 1.055–1.232; p = 0.001), as well as between CRP and 28-day sepsis-related mortality (OR = 1.241; 95% CI: 1.034–1.489; p = 0.020). Platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) levels were also elevated in sepsis (OR = 1.136; 95% CI: 1.003–1.286; p = 0.044). Mediation analysis indicated that CRP mediated the effects of IL-6 and RANTES on sepsis, accounting for 25.87% (OR = 0.980; 95% CI: 0.961–0.998) and 2.04% (OR = 1.002; 95% CI: 0.991–1.012) of the total effect, respectively. The robustness of these associations was confirmed through leave-one-out sensitivity analysis and funnel plots.

Conclusions. This study enhances our understanding of the mechanisms underlying sepsis and its associated mortality, and underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting inflammatory factors in its management.

Key words: C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, sepsis, Mendelian randomization analysis, circulating inflammatory factors

Background

Sepsis is a syndrome characterized by a systemic inflammatory response triggered by infection of the host with pathogenic agents such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, and it is often secondary to trauma, burns or shock.1, 2, 3 This condition frequently leads to dysfunction or failure of multiple organs, posing a serious threat to human life. It has been reported that the global burden of sepsis includes 48.9 million cases and 11 million sepsis-related deaths annually,4 while the overall incidence of sepsis among intensive care unit (ICU) patients in Asian countries is 22.4%.

The 30-day mortality rate of sepsis is approx. 17.4%, while that of severe sepsis can reach 26%, and may rise to 32.6% in low- and middle-income countries.5, 6, 7 Additionally, studies have reported that the incidence of sepsis can be as high as 38.6%, with mortality rates reaching 43.0% and continuing to increase at an alarming pace.8, 9, 10 Sepsis remains a major focus in the field of critical and emergency medicine, underscoring the urgent need to deepen our understanding of its pathophysiology, improve prevention strategies, and strengthen therapeutic approaches.

Identifying the etiology of sepsis is essential for reducing its incidence and improving treatment outcomes. The physiological and pathological processes of sepsis are highly complex, but the systemic inflammatory response remains one of its core pathological mechanisms. An excessive inflammatory reaction can lead to organ dysfunction in sepsis. Numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated significant increases in the protein levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in the liver tissue of septic rats.11

Serum concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10 are markedly elevated in rats with sepsis.12 In cellular models of sepsis, the secretion of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β increases sharply, amplifying the inflammatory response.13, 14 Clinical studies have confirmed these findings, demonstrating that procalcitonin (PCT) serves as a potential indicator of disease severity, whereas IL-6 is associated with the clinical progression of the syndrome.15 Both PCT and C-reactive protein (CRP) are significantly upregulated in sepsis.16 Moreover, increased IL-27 levels and decreased RANTES concentrations have been observed in neonates with sepsis.17

Observational studies often carry a risk of bias and false associations. The Mendelian randomization (MR) approach addresses this limitation by using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to infer causality. Mendelian randomization reduces confounding factors and bias, providing stronger evidence for causal relationships.18, 19 The two-sample MR method further minimizes distortion and interference by employing pooled statistical data from multiple studies. Moreover, this approach has been widely applied to improve causal inference through larger sample sizes and greater statistical power.

Objectives

To identify potential causal relationships and mediators between inflammatory factors and sepsis, this study employed a bidirectional MR design combined with mediation analysis. Additionally, the study aimed to provide guidance for the development of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies based on 41 circulating inflammatory factors (Table 1), as well as CRP and procalcitonin PCT, which may assist in the early diagnosis and treatment of sepsis.

Materials and methods

Research design

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) is a research approach used to identify genetic variants associated with specific diseases or traits. This method involves scanning the entire genome of a large number of individuals to detect genetic markers linked to the condition or characteristic of interest. The present study is based on the most recent and comprehensive GWAS datasets from large populations to investigate the causal relationships of CRP, PCT and 41 circulating inflammatory factors with sepsis and 28-day mortality.

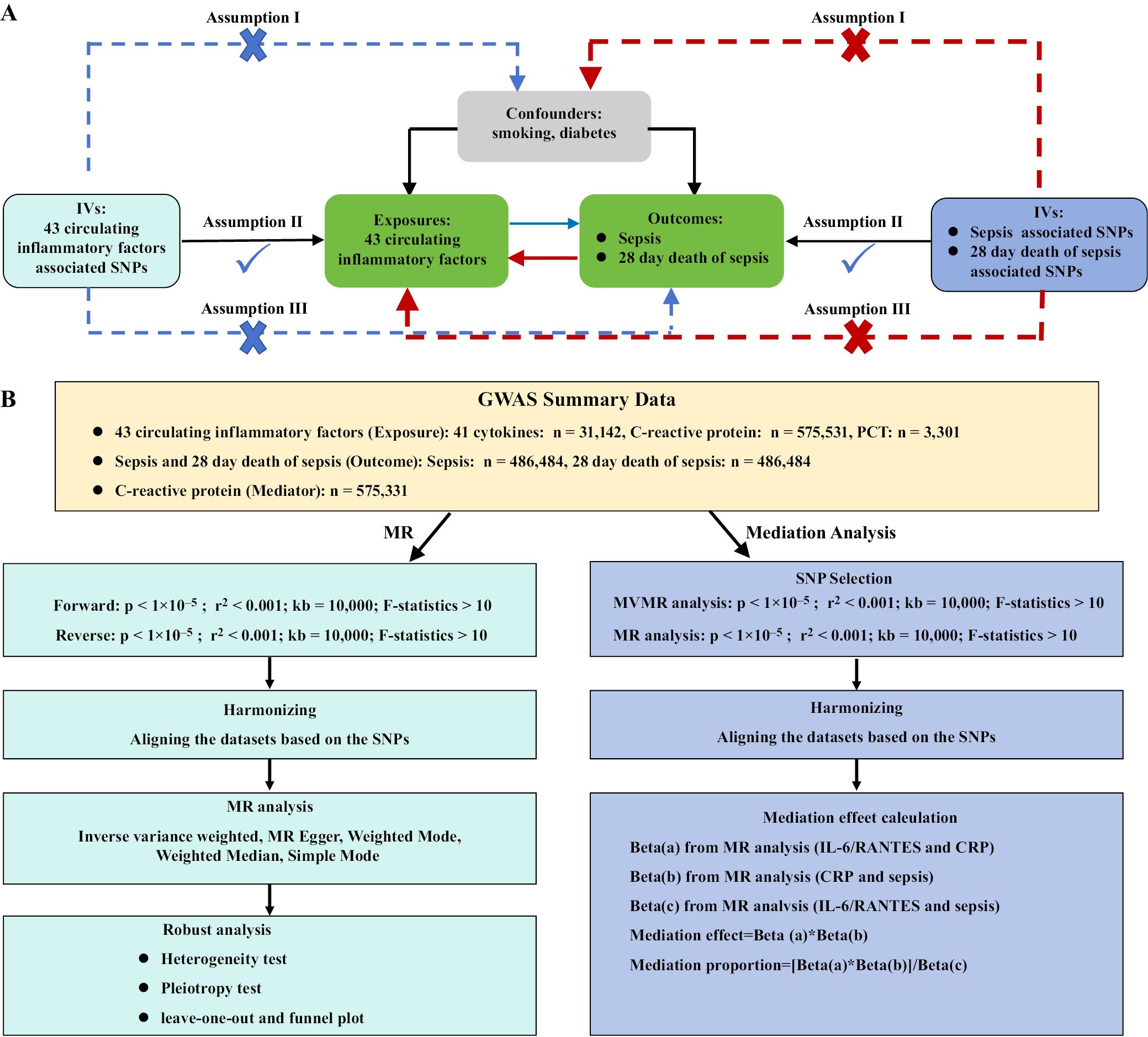

To ensure the validity of the research findings, the IV model in MR must satisfy 3 key assumptions: 1) the genetic variants are strongly associated with the exposure variables; 2) the genetic variants are independent of confounding factors that may influence the results (e.g., smoking, diabetes); and 3) the genetic variants affect the outcome variables only through the exposure variables. The overall research process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Collection of data on circulating inflammatory factors

Genetic instruments for the 41 circulating inflammatory factors were obtained from the most recent and comprehensive GWAS datasets, which combined summary statistics from 3 Finnish cohorts – the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study, FINRISK 1997, and FINRISK 2002 (n = 8,293);20, 21 13 European-ancestry cohorts (n = 21,758);22 and the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (n = 1,091).23 The GWAS data on 41 circulating inflammatory factors involved a total of 31,142 individuals.

The GWAS data for CRP were obtained from the UK Biobank (n = 427,367) and the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium (n = 148,164), comprising a total of 575,531 participants.24 The GWAS data for PCT were derived from 3,301 healthy participants from the INTERVAL study.25

Further details regarding genomic (GM) statistics are available in the original publications. As indicated in Supplementary Table 1, the IEU OpenGWAS project also provides access to the corresponding GWAS datasets.

Collection of sepsis datasets

The OpenGWAS database includes summary statistics for sepsis and sepsis-related 28-day mortality, obtained from the IEU OpenGWAS project, which is based on data from the UK Biobank.26 This dataset comprises 11,643 sepsis patients of European ancestry and 474,841 controls, with a total of 12,243,539 SNP loci analyzed. Patients were classified as having confirmed sepsis according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 and ICD-10) codes.4 Because data on circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis were obtained from different research projects, there was no sample overlap. As this study did not involve the collection of individual participant data, ethical approval was not required.

Selection of genetic instrumental variables

First, a strong correlation must exist between the exposure factors and the instrumental variables selected for analysis. To ensure adequate screening of instrumental variables, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with p-values below the genome-wide significance threshold (1 × 10–5) were selected. Subsequently, the genetic distance was set to 10,000 kb, and the linkage disequilibrium (LD) parameter (R2) for the SNPs was set to 0.001. Next, we calculated the F-statistic using the formula:

F = [(R2/(1 − R2)) × (N − K − 1)/K]

Instrumental variables with F-values <10 were excluded to ensure a strong correlation between the exposure factors and IVs. Additionally, IVs showing associations with outcome variables at a p-value < 1.0 × 10–5 were removed. The Phenoscanner database27 (http://www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk/) was used to identify and exclude potential confounding factors (e.g., smoking, diabetes) related to the IVs. Finally, the exposure and outcome datasets were harmonized to remove non-concordant SNPs, leaving the remaining SNPs as valid genetic instrumental variables.

Bidirectional MR analysis

A bidirectional MR approach was used to assess the causal relationships between circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis. Mendelian randomization analysis was performed using the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method as the primary analytical strategy. The IVW approach combines all SNPs in a meta-analysis framework to generate a pooled causal estimate. Four additional complementary methods – MR-Egger, weighted mode, weighted median, and simple mode – were also applied. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the MR-Egger and weighted median methods. When IVs account for at least half of the total weight in the analysis, the weighted median method provides robust and reliable causal estimates.

Pleiotropy was assessed and corrected using the MR-Egger intercept test. Heterogeneity among SNPs selected for each exposure variable was evaluated by calculating Cochran’s Q statistic. The Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO) method was applied to detect outliers and provide corrected causal estimates. The p-value from the MR-Egger intercept test was used to assess the presence of pleiotropy among SNPs. A nonsignificant difference between Q and Q’ (p > 0.05) indicated that the IVW model was more appropriate for the analysis. Sensitivity analyses, including the leave-one-out method and funnel plots, were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the results and identify potential outliers.

After Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, a p-value < 0.001 (0.05/43) was considered indicative of a strong causal relationship, whereas p-values between 0.001 and 0.05 were regarded as evidence of a general association. Reverse causality analyses were performed using MR, MR-PRESSO, and the TwoSampleMR package in R v. 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The results were reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology–Mendelian Randomization (STROBE-MR) guidelines (Supplementary Table 2).28

Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis is a statistical approach used to examine the mechanisms through which an independent variable (X) influences a dependent variable (Y) via a mediator (M). The objective is to determine whether the effect of X on Y is direct or occurs indirectly through M. This technique is particularly valuable for identifying the underlying pathways that explain relationships between variables. In this study, we applied a simple mediation model in which the independent variables (41 circulating inflammatory factors) influence the mediator (CRP), which in turn affects the dependent variables (sepsis and sepsis-related 28-day mortality).

The effects of the 41 circulating inflammatory factors on sepsis and sepsis-related 28-day mortality can be divided into direct and indirect components. The indirect effect represents the influence of these inflammatory factors on sepsis and 28-day mortality mediated through CRP, whereas the direct effect reflects their influence independent of CRP.29 The proportion of the total effect explained by mediation was estimated by dividing the indirect effect by the overall effect and calculating the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using the delta method.

Results

Selection of genetic IVs

We screened IVs for CRP, PCT and 41 circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis, respectively. Ultimately, 1,198 SNPs for inflammatory factor, 627 sepsis-associated SNPs, and 1,036 SNPs related to 28-day mortality of sepsis were included. The F-statistics of the genetic IVs that were strongly correlated with inflammatory factors were all greater than 10, indicating a low likelihood of bias influencing the estimates (Supplementary Tables 3,4).

Two-sample MR

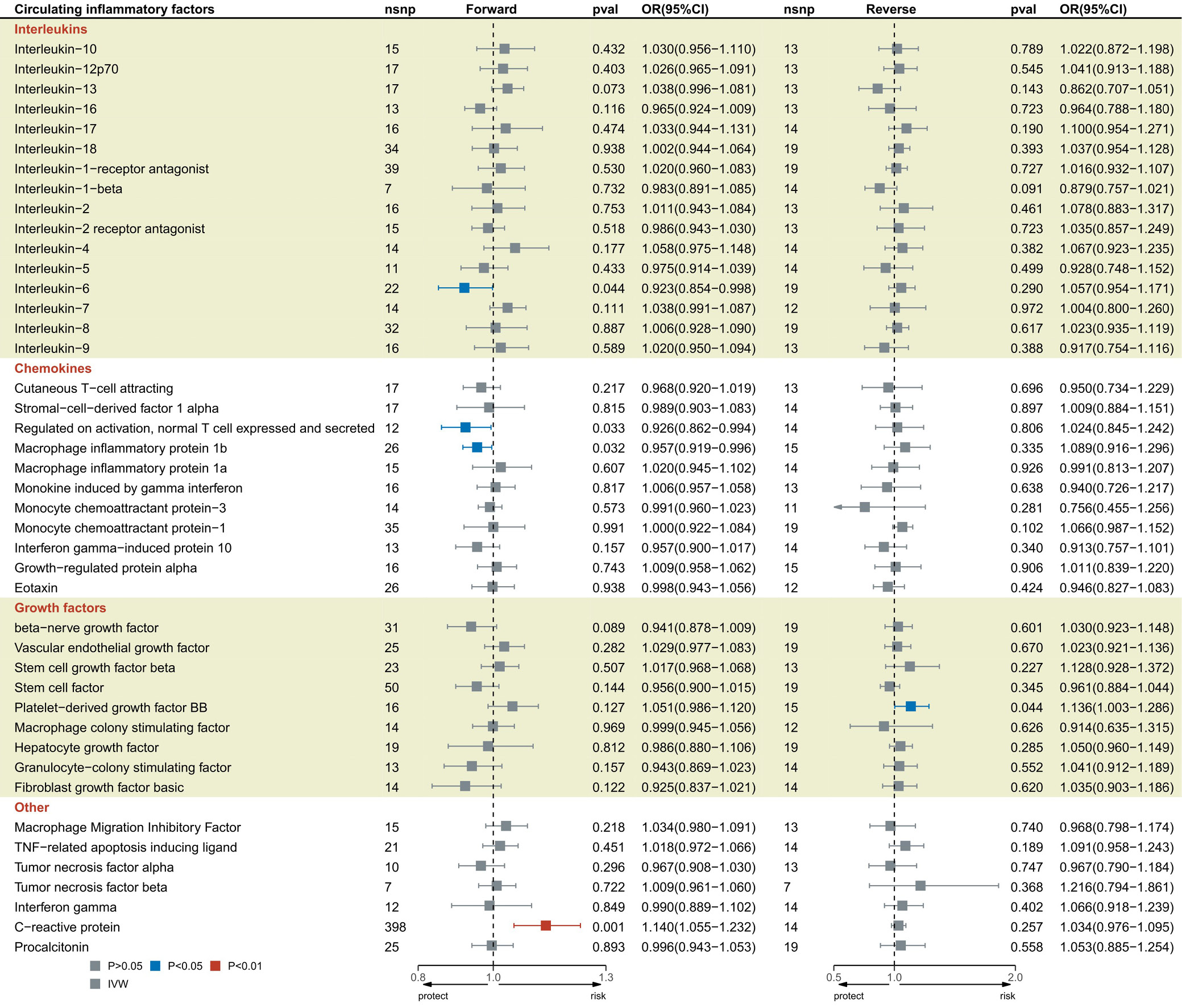

Impacts of 41 circulating inflammatory factors, CRP, and PCT on sepsis

This study identified 2 causal correlations between CRP, PCT and 41 circulating inflammatory factors and the risk of sepsis (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 3). Interleukin 6 (odds ratio (OR) = 0.923, 95% CI: 0.854–0.998; p = 0.044), RANTES (OR = 0.926, 95% CI: 0.862–0.994; p = 0.033), and macrophage inflammatory protein 1 beta (MIP1β) (OR = 0.957, 95% CI: 0.919–0.996; p = 0.032) were all related to the reduced risk of sepsis. Elevated CRP levels were positively associated with the risk of sepsis (OR = 1.140, 95% CI: 1.055–1.232; p = 0.001). Platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGFbb) noticeably increased in sepsis (OR = 1.136, CI: 1.003–1.286; p = 0.044). According to Cochran’s Q test results, the selected SNPs did not exhibit significant heterogeneity (p > 0.05; Supplementary Table 5). Similarly, the MR-Egger intercept test indicated no evidence of pleiotropy or outliers (p > 0.05; Supplementary Table 5). Finally, the leave-one-out analysis confirmed the robustness of the results (Supplementary Fig. 1–5).

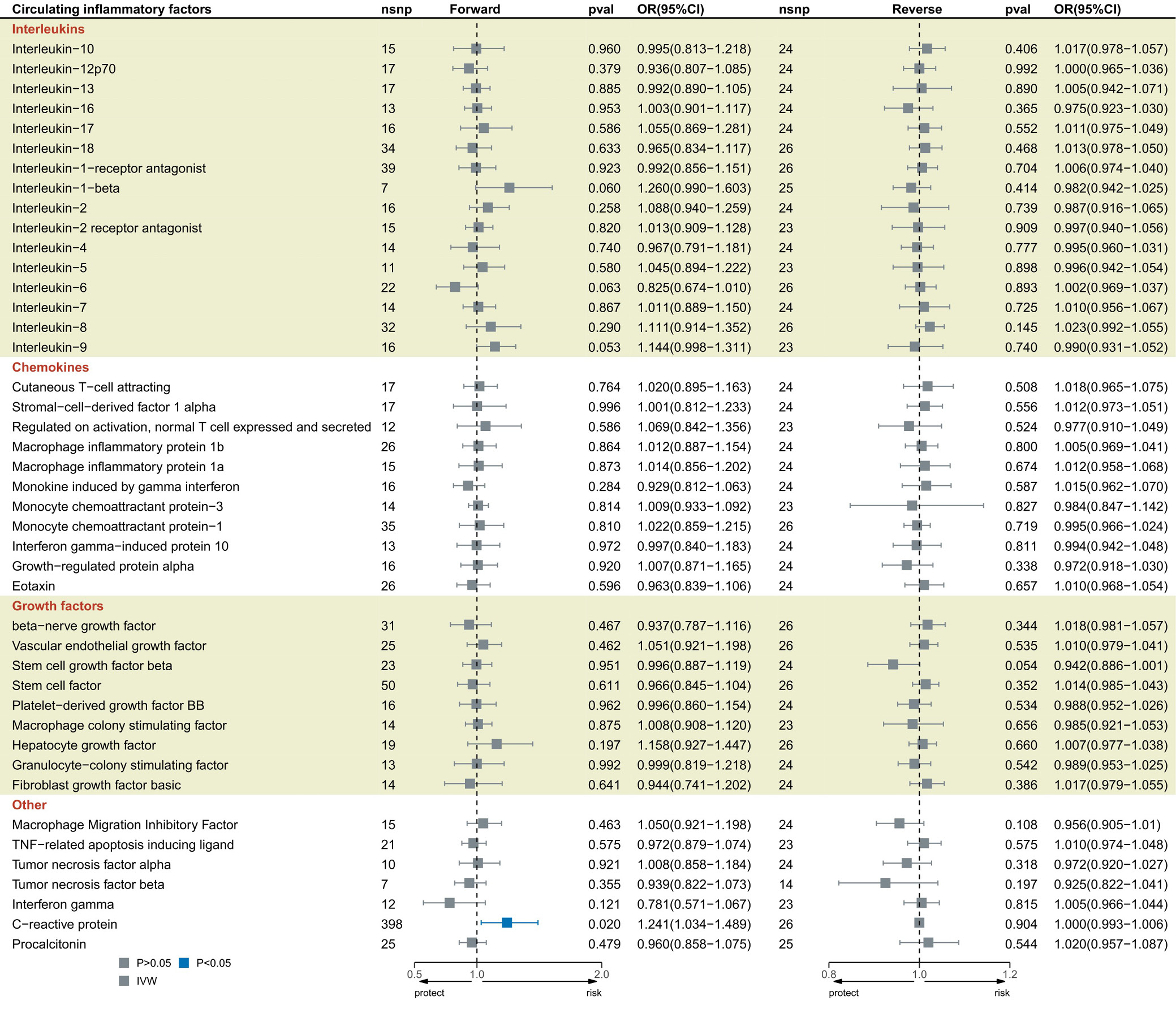

The influence of 41 circulating inflammatory factors, CRP, and PCT on the 28-day mortality of sepsis

The IVW results indicated that CRP, PCT and the 41 circulating inflammatory factors were causally associated with 28-day sepsis-related mortality (Figure 3; Supplementary Table 4). Genetically predicted CRP was associated with an increased risk of 28-day sepsis mortality (OR = 1.241; 95% CI: 1.034–1.489; p = 0.020). Cochran’s Q test results showed no significant heterogeneity among the selected SNPs (p > 0.05; Supplementary Table 6), and the MR-Egger intercept test revealed no evidence of pleiotropy or outliers (p > 0.05; Supplementary Table 6). Finally, the leave-one-out analysis and funnel plot confirmed the stability of the CRP results (Supplementary Fig. 11,12). The Bonferroni-corrected analysis revealed a strong association between CRP levels and the prevalence of sepsis, although this does not imply direct causation (OR = 1.140; 95% CI: 1.055–1.232; p = 0.001).

The mediating proportion of CRP in the relation between 41 circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis

We analyzed whether CRP acted as a mediator to strengthen the effects of 41 circulating inflammatory factors on sepsis. It was found that IL-6 and RANTES were associated with elevated CRP, and in turn, elevated CRP correlated with an enhanced risk of sepsis. As presented in Supplementary Table 7, our research showed that the mediating proportion of CRP in IL-6-based prediction of sepsis was 25.87% (OR = 0.980, 95% CI: 0.961–0.998), and that of CRP in RANTES-based prediction of sepsis was 2.04% (OR = 1.002, 95% CI: 0.991–1.012).

Discussion

This research evaluated the causation between CRP, PCT and 41 circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis/28-day sepsis-associated mortality. Also, mediation analysis was utilized to reveal the mediators of their causal relationships. Important findings were obtained: IL-6, RANTES and MIP1β were protective factors for sepsis, while CRP was a risk factor for the onset and 28-day mortality of sepsis. No significant causal relationships were observed between 39 inflammatory factors – including IL-10, PCT and β-NGF – and sepsis or 28-day sepsis-related mortality. Sepsis was identified as the cause of elevated PDGFbb levels. The mediation analysis indicated that the CRP-mediated predictive contribution of IL-6 and RANTES to the onset of sepsis was 25.87% and 2.04%, respectively.

The abnormal production and regulation of inflammatory factors play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Imbalances in these mediators can trigger dysregulated immune responses, leading to an excessive inflammatory cascade. Interleukin 6 is produced rapidly and transiently during infection or trauma, contributing to host defense by promoting acute-phase responses, hematopoiesis and immune activation, thereby playing a key role in the inflammatory process.30, 31

Several previous studies have examined the relationship between IL-6 and sepsis. Clinical research has shown that IL-6 levels are elevated in septic patients admitted to the ICU,32, 33 and that IL-6 is strongly correlated with sepsis severity.34 These findings suggest that IL-6 may serve as a potential biomarker for disease severity in sepsis. Elevated IL-6 levels may also indicate treatment response and prognosis.35 This conclusion is further supported by animal studies.36 Moreover, the combined measurement of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 has demonstrated strong predictive value for sepsis-associated myocardial injury and is closely related to patient outcomes.37

However, our research findings did not support these conclusions. More studies are necessary in the future to elucidate the causation. While some studies have shown that IL-6 can have protective effects in specific contexts, such as protecting cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress at the early stage of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced sepsis, it is important to note that literature and experimental results show that IL-6 is a complex marker with both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory roles in sepsis. Given the complex and dual roles of IL-6 in sepsis, clinicians should interpret elevated IL-6 levels with caution.

RANTES is a chemokine involved in regulating cell migration, and its levels progressively increase during infection in patients with sepsis.38, 39 Elevated concentrations of RANTES have also been observed in plasma samples from cats with sepsis and septic shock.40 A small-scale MR analysis previously reported that higher RANTES levels were associated with a reduced risk of sepsis,2 indirectly supporting our findings that elevated RANTES concentrations may be protective. RANTES plays an important role in promoting inflammation and activating other inflammatory mediators such as IL-6. It may serve as an early biomarker of inflammation, aiding in the early diagnosis and monitoring of sepsis. However, similar to CRP, these markers should be interpreted with caution.

Clinical evidence shows no noticeable correlation of MIP1β with the high risk of sepsis.41 However, an opposite conclusion was proposed in another prospective and retrospective case-control study that MIP1β acted as a useful clinical marker in children with sepsis, distinguishing it from other febrile illnesses.42 Another prospective clinical study also corroborated that MIP1β could be applied to distinguish patients with and without sepsis. Our MR analysis illustrated that MIP1β shared a negative causal association with sepsis and might have a protective impact on sepsis, which warrants verification. Mechanistically, MIP1β is a member of the chemokine family with chemotactic and pro-inflammatory properties. The release of MIP1β can activate TCC88 at the site of infection, enhancing the host’s resistance to pathogens.43 Future research should further investigate its causal role in sepsis, particularly its influence on inflammatory pathways, and large-scale clinical studies are needed to validate its prognostic significance.

C-reactive protein is an acute-phase protein synthesized in response to cytokine secretion.44 Clinical observational studies have demonstrated that CRP possesses the highest diagnostic accuracy for sepsis45, 46 and serves as one of the most effective prognostic biomarkers for this condition,47 making it valuable for predicting treatment outcomes in sepsis.48

This research supports our results that CRP is a significant risk factor and acts as a mediator for IL-6 and RANTES to predict 25.87% and 2.04% of sepsis, respectively. Although our study demonstrates a strong link between CRP levels and the prevalence of sepsis, it is important to note that CRP is not an ideal indicator of therapy effectiveness and can be influenced by factors other than infection, such as trauma, surgery, immune system dysregulation, and medications. Given the complexity of sepsis and the multifactorial nature of CRP elevation, further studies are necessary to elucidate the exact role of CRP in the pathogenesis and management of sepsis. This will help in developing more accurate diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies.

It has been revealed that many inflammatory factors, including IL-1RA, IL-1β, IL-7, IL-4, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-16, IL-17, and IL-18, are feasible serum biomarkers for sepsis and exert a significant predictive role in the prognosis of this disease.2, 36, 37, 41, 42, 49, 50, 51, 52 CAP-1 and TNF-α levels are elevated in patients with sepsis.36, 49 While TNF-α is a key mediator of the inflammatory response in sepsis, genetic polymorphisms may influence individual susceptibility to its development.53

Studies have shown that sepsis is associated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) levels, while severe sepsis-related mortality or sequelae are linked to reduced interferon gamma (IFN-γ) concentrations.41 TRAIL levels are inversely correlated with sepsis severity,54 whereas PCT, IP10 and HGF have been identified as potential serum biomarkers with high diagnostic value and strong prognostic utility in sepsis.42, 50, 55 Serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) are remarkably correlated with the survival rate of septic patients.56, 57 Additionally, previous MR analyses have reported a positive causal relationship between beta nerve growth factor (β-NGF) and sepsis.2, 3 However, in our study, 39 of the circulating inflammatory factors examined did not show significant causal associations.

The reverse MR analysis showed an increase in PDGFbb in sepsis. Previous clinical and preclinical research results supported our finding that the PDGFbb levels are significantly elevated in sepsis.58 The mechanism of this correlation may be related to the inhibitory function of PDGFbb in immune cell activation and cytokine production. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB protects against sepsis by reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.58 This discovery suggests a potential role for PDGFbb in sepsis treatment. While our analysis suggests a potential role for PDGFbb in sepsis treatment, it is important to note that the current understanding of PDGFbb as a therapeutic target in sepsis is still in its early stages. Further studies are necessary to validate the therapeutic potential of PDGFbb and to explore its mechanisms of action in the context of sepsis.

To our knowledge, although previous studies have conducted two-sample MR analyses investigating the causal relationships between 41 circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis, our study offers distinct advantages and provides several novel and suggestive findings. Fang et al. used the MR approach to demonstrate that β-NGF increased the risk of sepsis, whereas RANTES and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) were associated with a reduced risk.2 However, their study employed a two-sample unidirectional MR design and was limited by a relatively small GWAS sample size.

Lin et al. conducted a two-sample bidirectional MR study, demonstrating that the predicted circulating RANTES, basic-FGF and β-NGF levels were causally correlated with changes in the risk of sepsis.3 However, these 2 MR analyses did not examine the association between inflammatory factors and sepsis-related mortality, nor did they perform mediation analysis.

Zhi et al. performed a bidirectional MR analysis of circulating inflammatory factors and 28-day sepsis-related mortality, revealing inverse associations between IL-10 and sepsis, as well as between MCP-1 and sepsis-related mortality. In contrast, elevated MIP1β concentrations showed a positive association with both the incidence and mortality of sepsis.59 However, their study did not include mediation analysis. In contrast, our research employed a bidirectional MR approach using the most recent and comprehensive GWAS datasets to investigate the risk of sepsis and 28-day mortality. Furthermore, we performed mediation analysis to identify potential mediators underlying the observed causal relationships. Notably, although previous MR analyses identified β-NGF and MCP-1 as significant factors, our results showed no significant causal associations between these 2 markers and the risk of sepsis or 28-day sepsis-related mortality. Meanwhile, CRP was identified as a significant predictor of sepsis onset and 28-day mortality, as well as the principal mediator through which IL-6 and RANTES influenced sepsis risk. In addition, PDGFbb emerged as a potential key therapeutic target for sepsis. Heterogeneity and pleiotropy were evaluated, and the results were rigorously tested using multiple sensitivity analyses, confirming the robustness and validity of our findings. C-reactive protein levels rise later than those of IL-6 and, therefore, are not an ideal indicator of therapeutic effectiveness. Although elevated CRP concentrations can indicate the presence of inflammation, they may also be influenced by non-infectious factors such as trauma, surgery or immune dysregulation. Our findings suggest a potential link between IL-6, RANTES, MIP1β, CRP, PDGFbb, and sepsis severity, but further studies are warranted to elucidate whether these biomarkers play a causative role in the progression of sepsis or if they are merely markers of the underlying disease process.

Limitations

The limitations should also be mentioned. First, because most of the participants recruited in GWAS are from Europe, this population restriction might limit the application of our findings to other populations. Second, although our findings identify the mediators and causal links between CRP, PCT and 41 circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis, the underlying mechanisms require more investigation.

Conclusions

We identified strong causal associations between IL-6, RANTES and MIP1β and the risk of sepsis. C-reactive protein showed a robust causal relationship with an increased risk of sepsis and was also associated with 28-day sepsis-related mortality. In contrast, 39 inflammatory factors, including IL-10, PCT and β-NGF, showed no significant causal relationships with sepsis risk or 28-day mortality. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB levels were elevated in septic patients. Moreover, CRP acted as a mediating factor in the effects of IL-6 and RANTES on sepsis. These findings may provide valuable insights for the early identification of sepsis and the development of potential therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15881855. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the effect of IL-6 on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the effect of RANTES on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the effect of MIP1β on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Fig. 4. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the effect of CRP on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the effect of sepsis on PDGF-BB levels.

Supplementary Fig. 6. Funnel plot assessing asymmetry in the MR estimates for the effect of IL-6 on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Fig. 7. Funnel plot assessing asymmetry in the MR estimates for the effect of RANTES on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Fig. 8. Funnel plot assessing asymmetry in the MR estimates for the effect of MIP1β on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Fig. 9. Funnel plot assessing asymmetry in the MR estimates for the effect of CRP on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Fig. 10. Funnel plot assessing asymmetry in the MR estimates for the effect of sepsis on PDGFbb levels.

Supplementary Fig. 11. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the effect of CRP on sepsis (28-day death) risk.

Supplementary Fig. 12. Funnel plot assessing asymmetry in the MR estimates for the effect of CRP on sepsis (28-day death) risk.

Supplementary Table 1. Sources and details of the GWAS summary statistics used for CRP, PCT and 41 circulating inflammatory factors.

Supplementary Table 2. Analytical methods used for MR and mediation analysis.

Supplementary Table 3. Bidirectional MR estimating causal effects between circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis risk.

Supplementary Table 4. Bidirectional MR results estimating causal effects between circulating inflammatory factors and sepsis (28-day death).

Supplementary Table 5. Heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy assessments for MR analyses of circulating inflammatory factors on sepsis risk.

Supplementary Table 6. Heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy assessments for MR analyses of circulating inflammatory factors on sepsis (28-day death).

Supplementary Table 7. Two-step MR analysis quantifying mediation effects of IL-6 and RANTES on the relationship between CRP and sepsis risk.

Data Availability Statement

Summaries of sepsis and circulating inflammatory factors were acquired from the IEU OpenGWAS Project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/) and OpenGWAS databases.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.