Abstract

Background. Human monkeypox is a zoonotic disease with increasing global prevalence. Although several studies have identified its potential risk factors, findings remain inconsistent, highlighting the need for a systematic evaluation.

Objectives. To systematically investigate risk factors associated with human monkeypox infections using meta-analysis.

Materials and methods. A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and The Cochrane Library databases was conducted on all records up to February 19, 2024. Eligible studies assessing risk factors for monkeypox were included. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated, and heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 statistics.

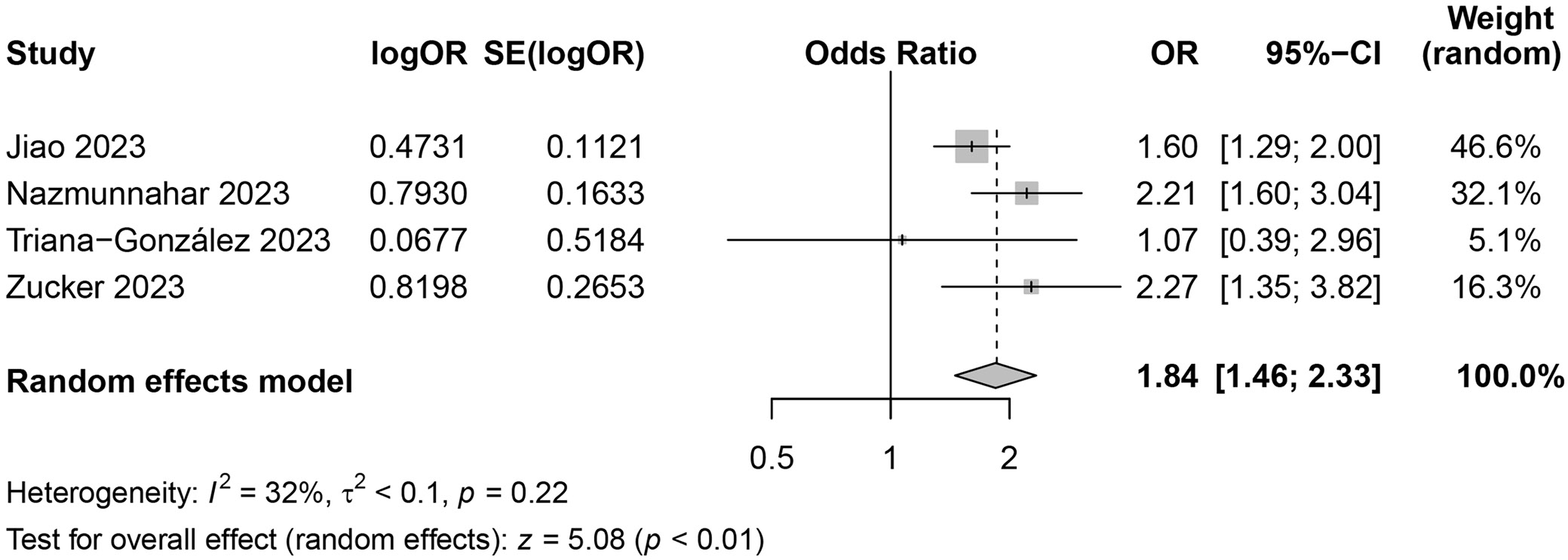

Results. Of the 1,844 articles identified, 9 studies met the inclusion criteria after screening, no publication bias was identified, and the meta-analysis results showed strong robustness. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection significantly increased monkeypox risk (OR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.13–4.34, p = 0.02, I2 = 93%). Concurrent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were also a significant risk factor (OR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.46–2.33), as was body mass index (BMI) higher than 30 kg/m2 (OR = 1.18, 95% CI: 0.19–7.53, p = 0.86), lower economic status (OR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.01–9.36, p = 0.52), education level (OR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.30–1.79, p = 0.50), or men who have sex with men (MSM) status (OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 0.84–1.75, p = 0.29).

Conclusions. HIV infection and concurrent STIs significantly increase monkeypox risk, underscoring the need for targeted prevention, including screening and risk reduction strategies in vulnerable populations, particularly MSM.

Key words: meta-analysis, risk assessment, virus, human monkeypox, literature search

Background

Human monkeypox is a sporadic zoonotic disease caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the orthopoxvirus genus.1, 2 The clinical presentation of monkeypox shares similarities with smallpox but is generally less severe, with key symptoms including fever, severe headaches, swollen lymph nodes, back pain, muscle aches, and fatigue.3 Within 1–3 days of the onset of fever, a characteristic rash typically develops, predominantly affecting the face and limbs. At this stage, individuals become contagious.

Monkeypox virus transmission occurs through direct contact with bodily fluids, lesions on the skin or mucous membranes, contaminated objects, or respiratory droplets from infected individuals.4 Two distinct genetic clades of MPXV have been identified: the Central African clade, which is associated with more severe disease, and the West African clade. The first human case of monkeypox was reported in 1970 in a 9-year-old boy from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Historically, human monkeypox was endemic to regions in West and Central Africa.1 However, in recent years, the incidence has been increasing.3 In 2022, a major outbreak occurred, involving more than 30 countries outside of Africa, including the UK, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Italy, the USA, and Canada.5, 6 This outbreak, the largest recorded outside Africa, prompted significant concern and led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a Public Health Emergency on July 23, 2022.7

As of September 2023, more than 90,000 cases of monkeypox had been confirmed globally, with over 30,000 reported in the USA.8 Studies indicate that monkeypox primarily spreads rapidly among men who have sex with men (MSM), rendering this group particularly vulnerable to infection.9 The modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA), an attenuated non-replicating orthopoxvirus, is currently the preferred vaccine for reducing the risk of human monkeypox infections.10 However, the global supply of vaccines falls significantly short of meeting the demand, particularly given the large population of MSM worldwide.9

Monkeypox continues to be a significant and ongoing threat to public health. The 2022 outbreak emphasized the urgent need to identify risk factors, particularly to safeguard vulnerable groups, including LGBTQ populations. Despite this urgency, existing studies are characterized by inconsistent findings, significant heterogeneity and the absence of standardized methodologies, which have hindered the development of effective prevention and treatment strategies. Furthermore, most research to date has been limited to descriptive epidemiology, lacking comprehensive analyses of potential risk factors. These limitations underscore the necessity of a systematic review and meta-analysis to consolidate available evidence, identify critical risk factors and provide actionable insights for improving clinical practice and public health responses.

Objectives

Based on current evidence, we hypothesized that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are significant risk factors for human monkeypox, particularly in vulnerable groups. To test this hypothesis, we designed this study to systematically analyze existing evidence and address 2 key research questions: 1) What are the main risk factors for human monkeypox infections? 2) Do these risk factors vary across different populations?

Materials and methods

Search strategies

To comprehensively evaluate the scientific evidence related to the risk assessment of human monkeypox infections, an integrated literature search strategy was developed in strict adherence to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines on databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and The Cochrane Library, covering records from the inception of each database to February 19, 2024. The search strategy was formulated using controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms) and free-text terms. For PubMed, the search strategy was as follows: (#1) (((((Monkeypox[MeSH Terms]) OR (Mpox[MeSH Terms])) OR (Orthopoxvirus infections[MeSH Terms])) OR (Monkeypox virus[MeSH Terms])) OR (Human Monkeypox[MeSH Terms])); (#2) (((Human Infection) OR (Human Illness)) OR (Infectious Disease)) OR (Infection); (#3) ((((Risk Factors[MeSH Terms]) OR (Epidemiology[MeSH Terms])) OR (Disease Surveillance[MeSH Terms])) OR (Public Health[MeSH Terms])) OR (Epidemiological Studies[MeSH Terms]); (#4) (((Risk Assessment) OR (Risk Evaluation)) OR (Risk Analysis)); (#5) (((#1) AND (#2)) AND (#3)) AND (#4). The detailed search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table 1. Logical operators and Boolean connectors were used for other databases, ensuring consistent search terms tailored to their respective syntaxes. Corresponding Chinese search terms were used for Chinese-language databases.

To ensure a comprehensive search, the reference lists of relevant studies and review articles were manually screened to identify additional eligible literature that may have been missed during the electronic database search. Grey literature was excluded to ensure methodological rigor. To handle duplicates, we employed systematic deduplication using bibliographic management software, followed by manual verification to identify studies recorded in multiple databases.

Literature inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) Original research on the risk assessment of human monkeypox infections, including but not limited to epidemiological studies, case-control studies, cohort studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and observational studies; 2) Research providing quantitative data on risk factors, epidemiological characteristics, clinical manifestations, or treatment outcomes of monkeypox infections; 3) Peer-reviewed and published articles; 4) Studies published in English or Chinese to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant research; 5) Studies with clear research design and methodology, including explicit research objectives, well-defined sample selection criteria, and robust data collection and analysis methods.

Literature exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: 1) Articles not subjected to peer review, including preprints, conference abstracts, expert opinions, and review articles; 2) Research not directly relevant to the study objectives, such as studies focused solely on the basic science of MPXV, animal models or non-human infection cases; 3) Studies with incomplete data or unclear findings; 4) For duplicate studies identified across multiple databases, only 1 version of the most complete study was retained.

Literature screening and data extraction

During the initial phase of literature screening, 2 researchers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the retrieved publications. Studies unrelated to the research topic were excluded based on the above inclusion and exclusion criteria. For publications that passed this preliminary screening, a full-text review was conducted to evaluate whether each study met the final inclusion criteria for analysis.

In the data extraction phase, 2 researchers independently extracted relevant information from each study using a standardized template comprising details such as the authors, publication year, study design, participant characteristics, and other essential data. Any disagreements during the data extraction process were resolved through open discussion or consultation with a 3rd researcher to ensure accuracy and consistency.

Quality and bias risk assessment of included literature

We evaluated the quality and risk of bias for the included studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS), a tool commonly used for observational studies. For cross-sectional studies, the assessment included checking how well the sample represented the population, whether the sample size was justified, how non-respondents were addressed and how exposure was measured. The comparability of studies was based on adjustments for important factors like age, sex and socioeconomic status. The outcome section focused on how the results were assessed and whether the statistical tests used were appropriate.

For case-control studies, the assessment looked at how cases and controls were defined and selected, whether they were comparable, and how exposure was measured. It also checked if the same method was used to measure exposure for both cases and controls and if non-responses were correctly handled.

Each study was given a score from 0 to 9. Scores of 6–9 indicated high quality, 4–5 meant moderate quality and 3 or less denoted low quality. Two reviewers carried out the assessments independently, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion or with help from a 3rd reviewer. This process ensured a consistent and fair evaluation.

Statistical analyses

A comprehensive meta-analysis was conducted to quantify the primary outcomes and effect sizes related to monkeypox infection risk assessment. Data analysis was performed using the R v. 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Combined odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated to estimate the pooled effect sizes. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic, where an I2 value greater than 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. A random-effects model was specified for all analyses, as it was anticipated that the studies would exhibit considerable variability in terms of participants, interventions, study designs, and outcome measures, which, in turn, suggests that the true effect size might differ across studies. Funnel plots and Egger’s regression tests were employed to assess potential publication bias. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Search results

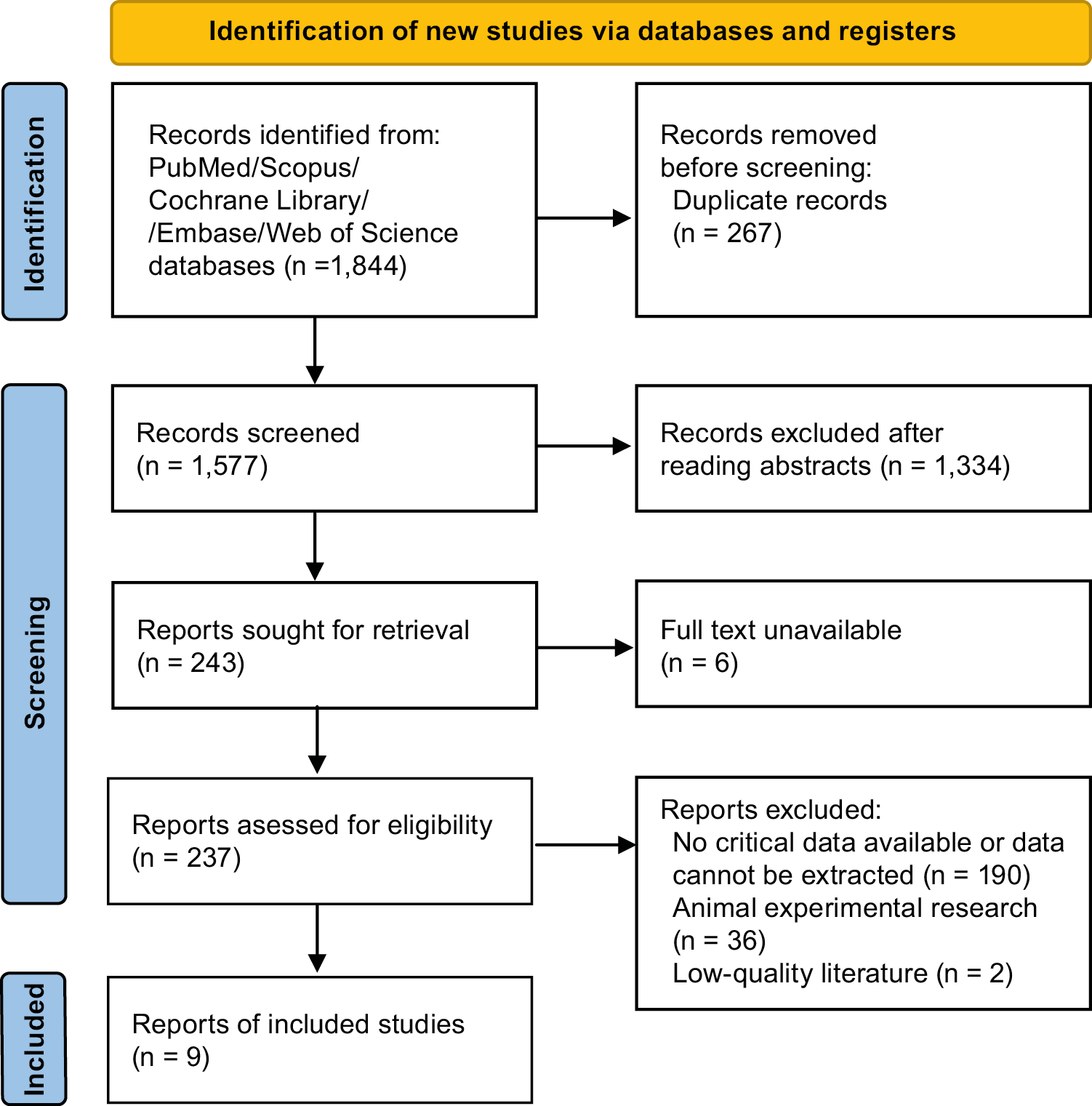

The initial database search identified 1,844 articles. After removing duplicates (n = 267), 1,577 records were screened based on their titles and abstracts. Of these, 1,334 articles were excluded as they were unrelated to the research objectives. Subsequently, 237 articles with accessible full texts were subjected to a thorough review in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. At this stage, 190 articles were excluded due to the absence of key data or because the data could not be extracted. Additionally, 36 studies involving animal experiments and 2 studies of poor quality were excluded. Ultimately, 9 studies met the inclusion criteria4, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Basic characteristics and quality assessment of literature

Most of the included studies were cross-sectional in design, while 1 was classified as a case-control study. Their sample sizes varied significantly, ranging from 72 to 8,088 participants. The median age of participants across the studies was 18 to 45 years, with the majority being male. The quality assessment of the included literature yielded scores ranging from 6 to 8, reflecting a moderate-to-high overall quality, and confirming that the studies met the quality standards required for inclusion in this analysis.

Meta-analysis results

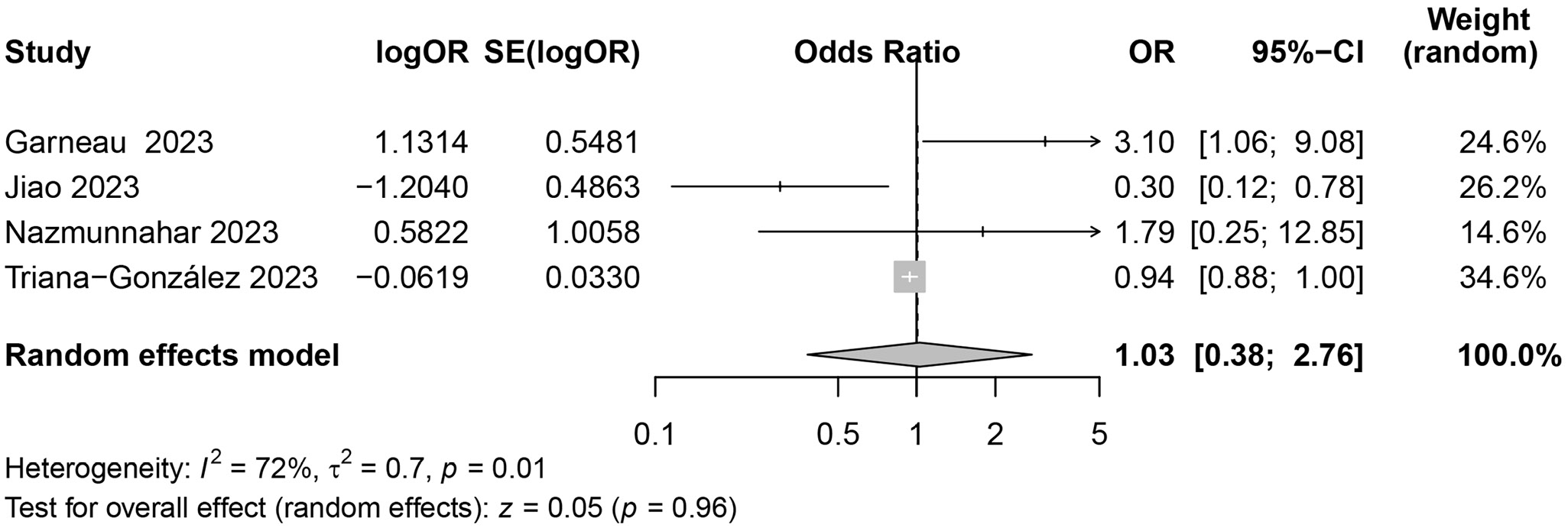

Age

This section examines whether demographic factors, such as age, contribute significantly to the risk of monkeypox infection. To assess the impact of age as a predictive factor for the risk of monkeypox infections, this meta-analysis included 4 studies covering various regions, populations and research designs. The analysis revealed high statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 72%, p = 0.01), which may indicate significant differences among the studies in terms of methodology, population characteristics, geographical locations, and age group categorization. The combined data showed that the overall effect size for age (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.38–2.76, p = 0.96) did not demonstrate statistical significance (Figure 2). The high heterogeneity observed across the included studies (I2 = 72%) suggests substantial variability in study design, population characteristics and age group categorizations.

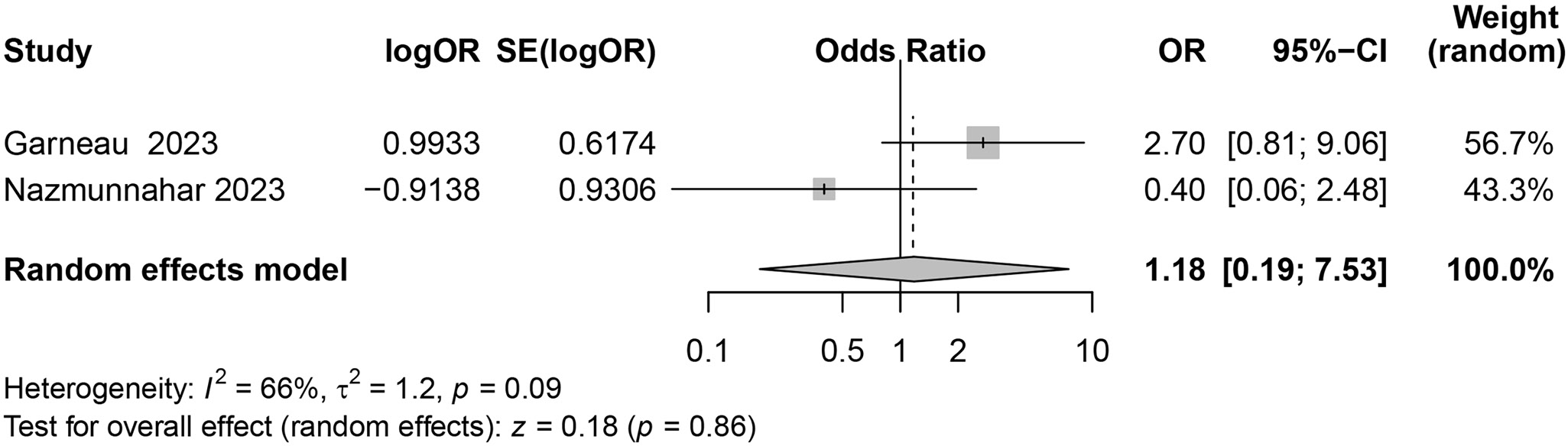

Body mass index >30 kg/m2

This meta-analysis synthesized the results of 2 studies to explore the potential impact of body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2 on the risk of monkeypox infections. The studies showed significant heterogeneity in the included literature (I2 = 66%, p = 0.09). The overall effect size (OR = 1.18, 95% CI: 0.19–7.53, p = 0.86) suggested that BMI > 30 kg/m2 did not constitute a significant risk factor for monkeypox infections (Figure 3). The analysis revealed substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 66%), potentially reflecting differences in sample sizes and study populations.

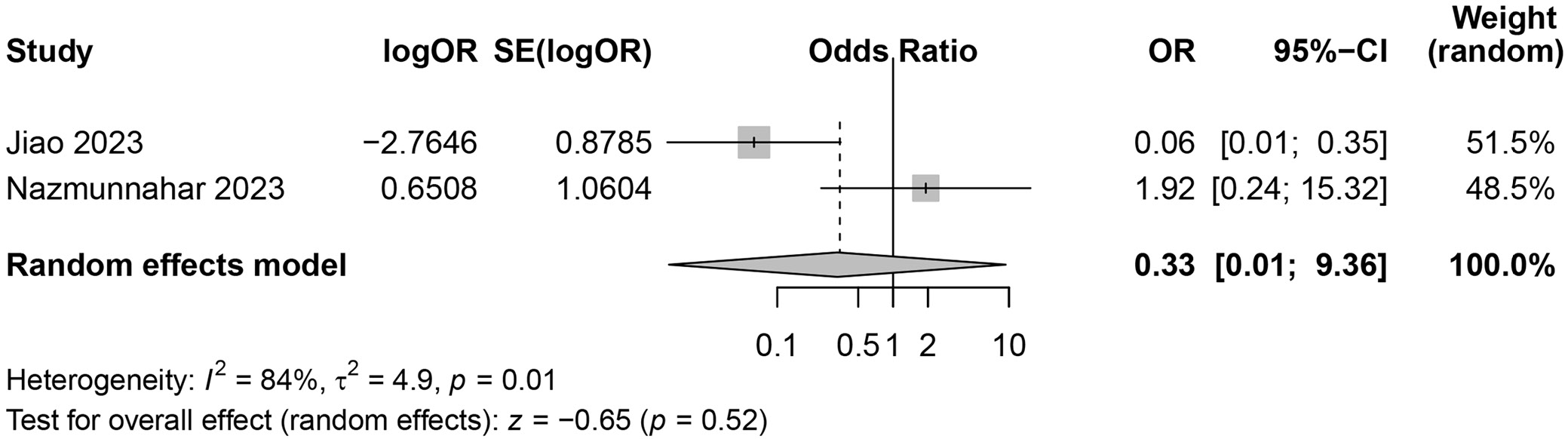

Economic status

Economic status was assessed to determine whether lower income levels increase susceptibility to monkeypox. Results from 2 studies were synthesized when the meta-analysis was adopted to assess the potential impact of economic status on monkeypox infection risk. The heterogeneity test indicated the significant heterogeneity between the included studies (I2 = 84%, p = 0.01). The combined overall effect size (OR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.01–9.36, p = 0.52) revealed that compared to higher economic status, lower economic status did not significantly increase the risk of monkeypox infections (Figure 4). The high heterogeneity observed (I2 = 84%) underscores the variability in how economic status was defined and measured across studies.

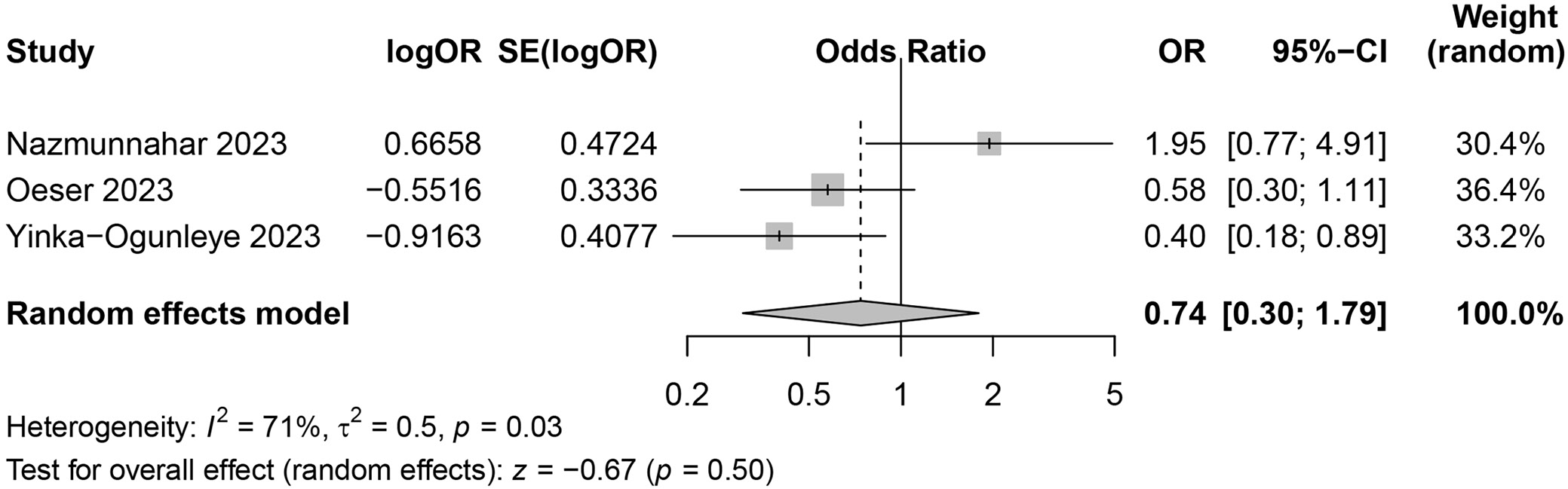

Education level

This meta-analysis combined the results of 3 studies to explore the potential impact of education level on the risk of monkeypox infections. The heterogeneity test revealed significant differences among the included studies (I2 = 71%, p = 0.03). The combined overall effect size (OR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.30–1.79, p = 0.50) revealed that the education level did not constitute a significant risk factor for monkeypox infections (Figure 5). Although education level was analyzed to evaluate its role in monkeypox risk, the significant heterogeneity (I2 = 71%) may arise from variations in educational systems and participant awareness in different regions.

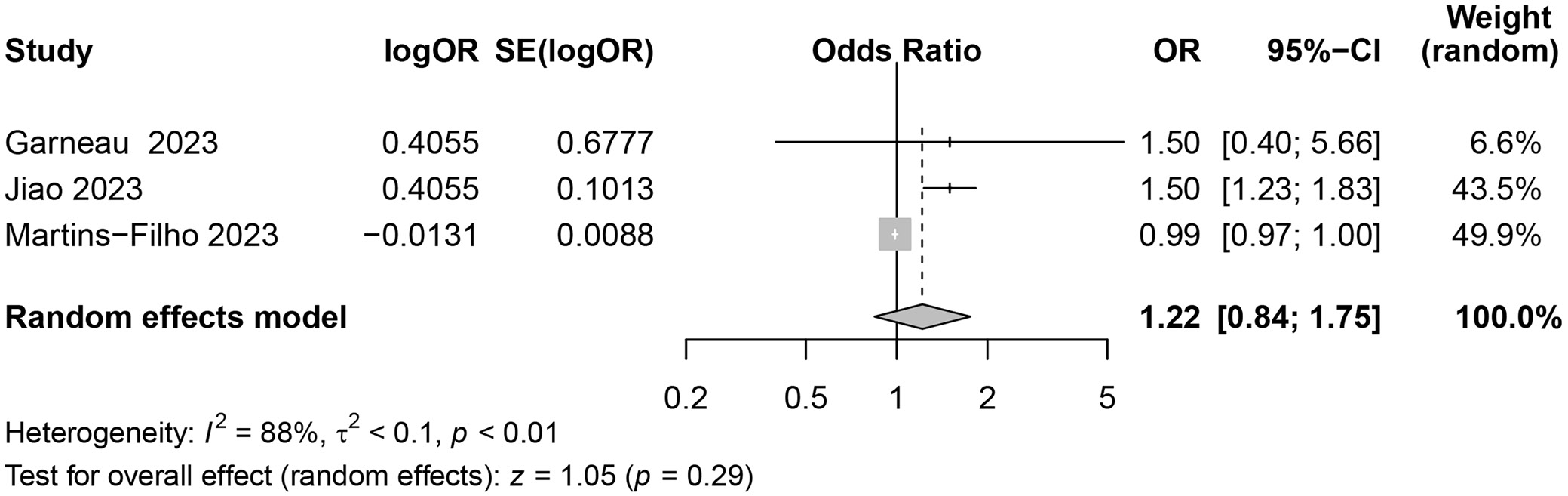

Men who have sex with men

This meta-analysis synthesized the results of 4 studies to explore the potential impact of MSM on the risk of monkeypox infections. The heterogeneity test revealed significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 88%, p < 0.01). The combined overall effect size (OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 0.84–1.75, p = 0.29) indicated that the MSM did not significantly increase the risk of monkeypox infections (Figure 6), likely due to differences in clinical presentations, symptom recognition and healthcare access within this population.

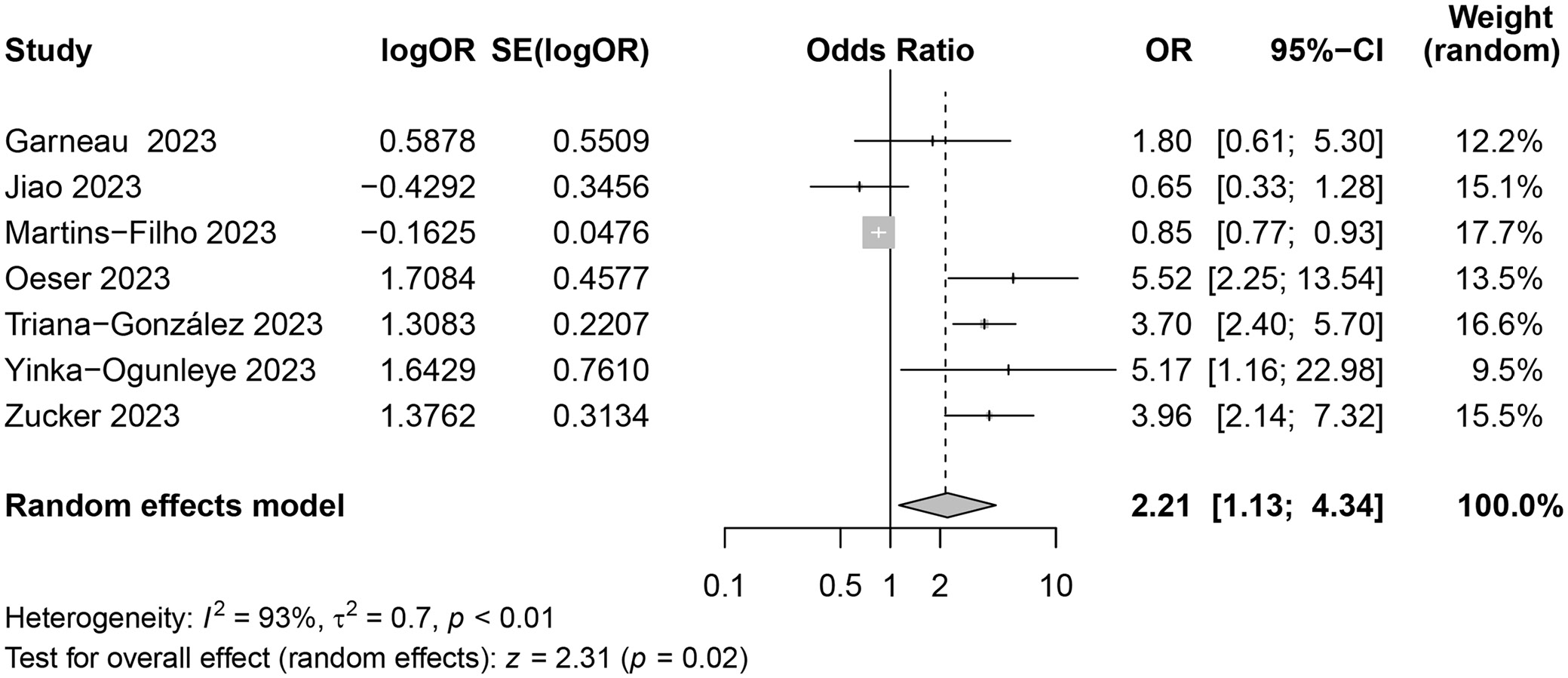

Human immunodeficiency virus infections

The association between HIV infection and monkeypox risk was explored. This meta-analysis synthesized the results of 7 studies to explore the potential impact of HIV infections on the risk of monkeypox infections. The heterogeneity test indicated the high heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 93%, p < 0.01). The combined overall effect size (OR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.13–4.34, p = 0.02) demonstrated that HIV infections significantly increased the risk of monkeypox infections (Figure 7). Despite high heterogeneity (I2 = 93%), the findings consistently demonstrate a significant increase in risk, highlighting the impact of immune suppression.

Other concurrent sexually transmitted infections

This meta-analysis combined the results of 4 studies to discuss the potential impact of other concurrent STIs on the risk of monkeypox infections. The heterogeneity test revealed relatively low heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 32%, p = 0.22). The combined overall effect size (OR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.46–2.33, p < 0.01) indicated that other concurrent STIs significantly raised the risk of monkeypox infections (Figure 8). The influence of concurrent STIs on monkeypox risk, with the relatively low heterogeneity (I2 = 32%), suggests that damaged mucosal barriers may facilitate viral transmission.

Publication bias

A funnel plot was constructed to assess potential publication bias. The analysis revealed some studies lying outside the funnel, with noticeable asymmetry (Supplementary Fig. 1). To further evaluate publication bias quantitatively, Egger’s test was applied. This regression-based method examined the relationship between effect size estimates and their standard errors (SEs). The results indicated minimal publication bias among the included studies.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the robustness of the results. By sequentially excluding each study and reassessing the individual contributions, minimal changes were observed in the combined effect size and its CI, demonstrating consistent findings (Supplementary Fig. 2,3). These results suggest that the study findings are robust and reliable.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive and robust risk assessment of human monkeypox infections, distinguishing itself from previous research by integrating diverse datasets in a meta-analysis. Unlike earlier studies, which primarily focused on descriptive epidemiology or isolated populations, this work consolidates findings across multiple regions and populations, providing a global perspective on risk factors. Additionally, the analysis incorporated stringent quality assessments and addressed heterogeneity through advanced statistical modeling. Importantly, the findings challenge previous assumptions about the influence of socioeconomic and demographic factors, while reinforcing the roles of HIV infection and concurrent STIs as significant risk factors. For instance, the data revealed that age, BMI > 30 kg/m2, lower economic status, education level, and MSM status did not significantly increase the risk of monkeypox infections. However, HIV infections and the presence of other STIs were significantly associated with an elevated risk of monkeypox infections. Overall, this study refines the understanding of monkeypox transmission dynamics and provides important insight into informing targeted public health strategies.

The risk assessment for human monkeypox infections is a complex issue influenced by various demographic and behavioral factors. Garneau et al.8 reported that age >40 years was not a risk factor for hospitalization in patients with monkeypox infections. Similarly, Jiao et al.11 conducted a large cross-sectional survey among young MSM in China and found no significant relationship between age and the perception of monkeypox infection risk. In contrast, another study demonstrated a significant association between perceived monkeypox infection risk and sociodemographic attributes, with younger age groups more likely to perceive moderate-to-high risk.13 This was attributed to their greater engagement with internet-based communication and increased health awareness in the digital era. Consequently, the age range of 18–35 years may not constitute a risk factor for monkeypox infections,17, 18 which aligns with the findings of our study, where age ranging from 18 to 45 years was not identified as significant risk factor for human monkeypox infections.

Some research suggests that BMI is a key factor in assessing the risk of viral infections, as obesity is linked to increased severity of infectious diseases.19 However, in this study, a BMI > 30 kg/m2 was not a significant risk factor for monkeypox infections. This may be attributed to the inclusion of individuals with only mild obesity, which may not be sufficient to significantly increase susceptibility to infection. Additionally, Cénat et al.20 indicated that low-income populations face higher risks of viral infections due to limited access to healthcare services, overcrowded living conditions and poor nutrition. Similarly, individuals with lower education levels may have reduced awareness of preventive measures or engage in behaviors that increase viral exposure.21, 22 While economic status and education level are important determinants of viral infections, the findings of this study revealed that neither factor significantly influenced the risk of monkeypox infections, and we hypothesized that this could be attributed to enhanced efforts in promoting awareness of human monkeypox prevention and other viral infections.

Data from the WHO showed that as of May 9, 2023, the monkeypox outbreak had spread to 111 countries or regions, with 87,314 cases reported globally. A distinctive feature of this outbreak was that most infections occurred in the MSM group. In contrast, the risk of monkeypox infections among the general population remains relatively low, suggesting MSM could represent a potential risk group.23 However, our meta-analysis findings indicated that MSM status was not a significant risk factor for monkeypox infections. This discrepancy may arise from the variability in the clinical presentation of monkeypox among confirmed MSM cases. Many cases exhibit atypical symptoms, with genital and perianal rashes often appearing as the first symptom, or even progressing to empyesis before systemic symptoms develop. These atypical presentations could lead to misdiagnoses within the MSM group, ultimately contributing to an insignificant risk assessment in this population.24

In the risk assessment of human monkeypox infections, HIV infections emerge as significant contributory factors. During the 2022 monkeypox outbreak, approx. 95% of global cases occurred among MSM, with 40% of these cases involving individuals with HIV infections. Surveys have revealed that HIV-positive MSM, primarily aged 18–40 years, are often sexually active, with some reporting more than 3 partners for oral or anal sex and engaging in group or heterosexual sexual activities. While it remains unconfirmed whether monkeypox is transmitted sexually, the detection of the virus in the semen of male patients suggests the potential for sexual transmission.25, 26 Individuals with lower CD4+ T-cell counts and uncontrolled HIV viral loads exhibit more severe symptoms of monkeypox. In the USA, although HIV-positive individuals account for only 38% of monkeypox cases, they represent up to 94% of monkeypox-related deaths. These observations strongly support the notion that HIV infection is a significant risk factor for human monkeypox infections.27 In this study, HIV infection was found to significantly increase the risk of monkeypox infection, consistent with findings from previous research. This increased risk can be attributed to 2 primary factors: the more pronounced clinical presentation of monkeypox in individuals with HIV and the immunosuppression associated with HIV infection, which reduces immune defense and increases susceptibility to monkeypox.28, 29

The presence of concurrent STIs further exacerbates the risk of human monkeypox transmission. Studies have demonstrated that monkeypox can occur in individuals with as little as 1 sexual encounter or those who are sexually active, with the risk amplified among MSM. Additionally, 41% of monkeypox patients reported a recent history of other STIs, such as chlamydia, gonorrhea or syphilis. These findings underscore the necessity of screening individuals diagnosed with monkeypox for HIV and other STIs.24, 30 The results of this study confirmed that concurrent STIs significantly increased the risk of monkeypox infection. This is likely because STIs can damage the skin barrier or mucosal surfaces, facilitating viral entry and spread. Based on these findings, prevention and control measures for human monkeypox should emphasize reducing high-risk behaviors, such as having multiple sexual partners among MSM, and actively screening for HIV and other STIs.

Lastly, vaccination is key to preventing monkeypox, especially in vulnerable groups such as MSM. However, the limited global supply of vaccines shows the need for other preventive measures alongside treatment strategies. Vaccines like the MVA can lower the risk of infection, but they are often unavailable in regions with new outbreaks. Early and regular screening for monkeypox, combined with proper management of HIV, is essential to reduce severe cases. Public health efforts should include educational campaigns to help MSM and the general public understand monkeypox symptoms and how it spreads. Vaccination programs should focus on high-risk groups, including MSM and people with HIV, while addressing vaccine shortages through better planning and international cooperation. Increasing access to antiviral treatments and setting up systems to track outbreaks would also help control the spread of monkeypox.

Limitations

However, this study has some limitations. The included studies primarily focused on specific regions and populations, such as MSM groups in developed countries, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other regions or demographic groups. Regional differences in healthcare systems and cultural factors may influence monkeypox transmission and risk factors. Additionally, small sample sizes in some studies, particularly for BMI, socioeconomic status and education level, reduced statistical power and may have contributed to nonsignificant results. Variability in study quality, as assessed with the NOS, and significant heterogeneity observed in certain analyses highlight the need for larger, high-quality studies involving diverse populations to validate these findings.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that age, BMI > 30 kg/m2, lower economic status, education level, and MSM status were not significant risk factors for human monkeypox infection, whereas HIV infection and concurrent STIs were identified as significant risk factors. Therefore, prevention and control measures for human monkeypox should focus on advocating reduced high-risk behaviors, such as limiting multiple sexual partners within the MSM population, and actively screening for HIV and other STIs. These findings provide valuable insights for implementing targeted and effective interventions to prevent and manage monkeypox infections.

Future research should focus on larger multicenter studies to validate these findings across diverse populations and geographic regions. Longitudinal studies are also needed to explore the long-term relationships between HIV, other STIs and monkeypox, particularly in immunocompromised populations. Additionally, efforts to standardize study designs and data collection methods would help reduce heterogeneity and improve comparability across studies. Taken together, the findings from this study could serve as a valuable reference to improve prevention and treatment strategies for human monkeypox infections.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15188222. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Search strategy.

Supplementary Fig. 1. Funnel plots for assessing publication bias. A. Age; B. BMI; C. Economic status; D. Education level; E. MSM status; F. HIV infection; G. Concurrent STIs.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Sensitivity analysis. A. Age; B. BMI; C. Economic status; D. Education level.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Sensitivity analysis. A. MSM status; B. HIV infection; C. STIs.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.