Abstract

Background. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complicated endocrinological disorder.

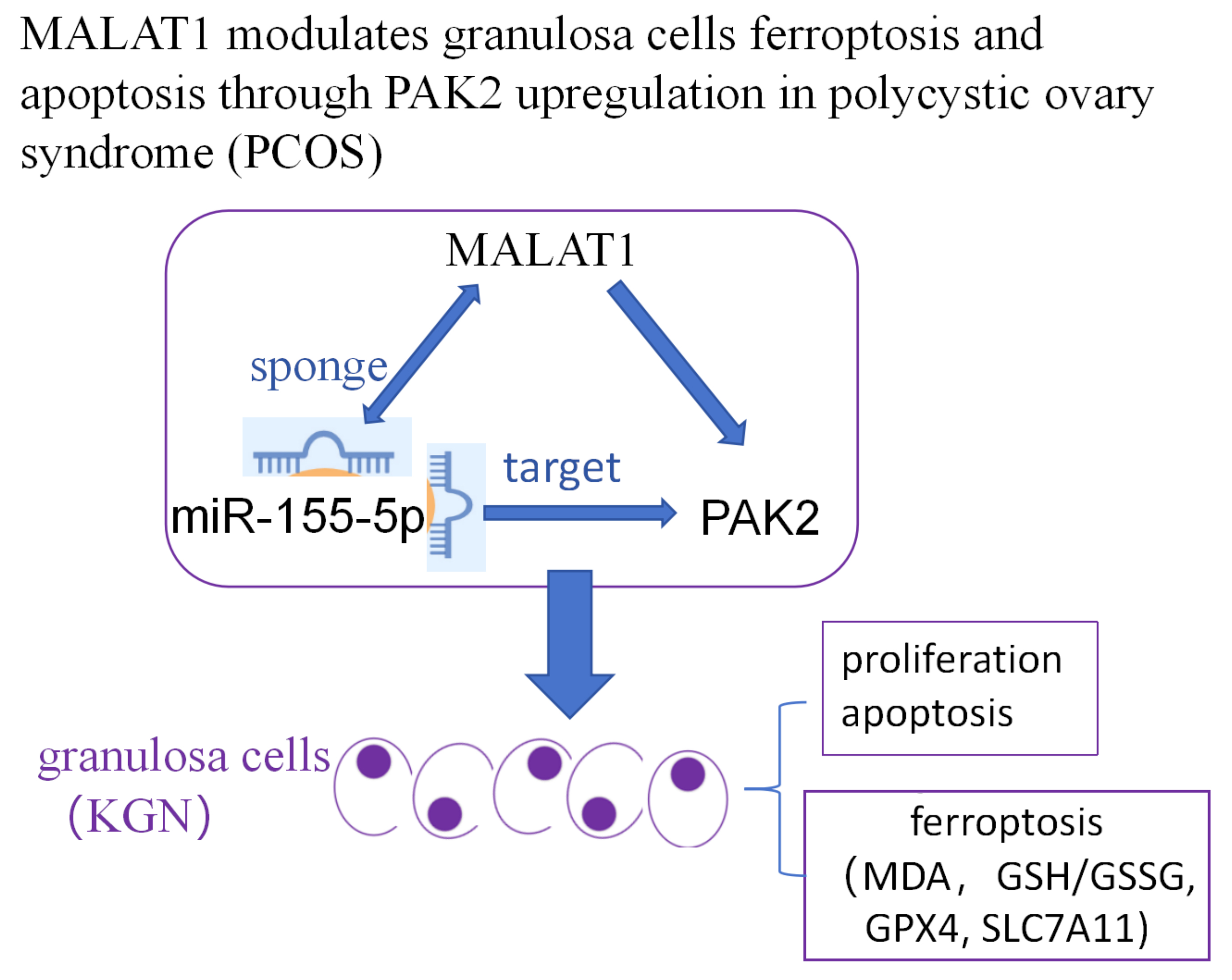

Objectives. We investigated the ferroptosis-regulated role of MALAT1 and its potential modulatory mechanisms in granulosa cells (GCs).

Materials and methods. Reverse transcripton quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was used to measure the relative expression of MALAT1/miR-155-5p/PAK2 in KGN cells after transfection. Online bioinformatic analysis was performed to predict the interactions between MALAT1/PAK2 and miR-155-5p. Dual luciferase assays were performed for relative luciferase activity in cell groups co-transfected with the pmiRGLO plasmids containing wild type (wt) or mutant type (mt) of MALAT1 (MALAT1-wt, MALAT1-mt), siRNA targeting MALAT1(si-MALAT1) miR-155-5p inhibitor or their control was transfected into KGN cells using Lipofectamine 2000. After 48 h, the transfected cells were collected for the following experiments. Cell viability and apoptosis were measured using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and flow cytometry. Malondialdehyde (MDA) level and reduced glutathione (GSH) / oxidized glutathione disulfide (GSSG) ratio were detected using commercial kits. Western blot was used to measure the relative protein changes in PAK2, SLC7A11 and GPX4.

Results. Knockdown of MALAT1 decreased cell viability, increased apoptosis and ferroptosis, which was reversed by miR-155-5p inhibition. MALAT1 downregulation inhibited PAK2, while miR-155-5p inhibition activated PAK2. The increase of relative luciferase activity in cells transfected with MALAT1-wt or PAK2-wt and miR-155-5p inhibitor suggests the bindings between miR-155-5p and MALAT1 or PAK2.

Conclusions. This study revealed a novel ferroptosis-modulated role of MALAT1 in PCOS in vitro via interactions with miR-155-5p/PAK2. Further in vivo and clinical studies are needed to validate these in vitro findings and fully assess the therapeutic potential of MALAT1 in PCOS.

Key words: PCOS, ferroptosis, MALAT1, PAK2

Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex endocrinological disorder affecting 8–13% of reproductive-aged women worldwide, with approx. 70% of cases remaining undiagnosed.1, 2 As an ovulatory disorder, PCOS is characterized by irregular menstrual patterns, metabolic disturbances and hyperandrogenism. However, the precise causes of PCOS remain unclear, and there is an urgent need for accurate and efficient diagnostic methods.3, 4 Beyond known risk factors such as obesity, elevated testosterone levels and male-pattern balding, previous studies have reported numerous genetic and protein alterations in patients with PCOS.5, 6 An increasing body of research suggests that noncoding RNAs may play an important role in the pathogenesis of PCOS.7 For example, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) BBOX1 antisense RNA1 (AS1) has been found to be upregulated in the follicular fluid of PCOS patients and is known to promote the proliferation of granulosa cells (GCs) by downregulating miR-19b.8 LncRNA HLA-F-AS1 is downregulated, while microRNA-613 expression is increased in the follicular fluid of PCOS patients; overexpression of HLA-F-AS1 has been shown to promote GC proliferation by inhibiting miR-613.9 Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript-1 (MALAT1) has been found to be downregulated in peripheral blood leukocytes from obese PCOS patients10 and similarly decreased in GCs from PCOS patients.11, 12 Previous studies have demonstrated that, in vitro, MALAT1 can regulate the viability and apoptosis of GCs and the human granulosa-like tumor cell line (KGN).13 In PCOS rat models, MALAT1 is also downregulated in ovarian tissues, and upregulation of MALAT1 has been shown to protect against PCOS via the miR-302d-3p/LIF axis.14 Mechanistically, MALAT1 modulates KGN cells and GCs in vitro through miR-125b/miR-203a/TGFβ signaling pathways.12 In GCs and KGN cells, MALAT1 promotes the degradation and ubiquitination of p53, thereby regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis.15 Recently, increased ferroptosis has been identified as being correlated with PCOS.7, 16 Ferroptosis in PCOS is associated with impaired mitochondrial dynamics, overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines and elevated oxidative stress.17 In PCOS rat models, inhibition of ferroptosis has been shown to significantly alleviate PCOS symptoms.7, 18 However, it remains unknown whether MALAT1 plays a role in mediating ferroptosis in KGN cells or GCs.

Objectives

Interestingly, using online bioinformatic tools, we identified that PAK2 may be regulated by MALAT1 through competitive binding to miR-155-5p. Downregulation of PAK2 in PCOS ovarian tissues has been shown to trigger oxidative stress via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and mediate apoptosis in KGN cells through the β-catenin/c-Myc/PKM2 signaling axis.19 Additionally, miR-155-5p has been reported to enhance glycolysis in KGN cells, which may be linked to increased cell proliferation.20 Based on these findings, we hypothesized that MALAT1 may play a regulatory role in the proliferation, apoptosis and ferroptosis of KGN cells through the miR-155-5p/PAK2 axis. This study primarily employed in vitro experiments to validate this hypothesis.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatic analysis

The StarBase online database (https://rnasysu.com/encori/agoClipRNA.php?source=lncRNA) was used to predict the binding sites between MALAT1, PAK2 and miR-155-5p. First, the potential binding sites between MALAT1 and miR-155-5p were predicted using the miRNA-Target (lncRNAs) option. Next, the binding sites between miR-155-5p and PAK2 were predicted using the miRNA-Target (mRNA) option.

Cell culture and transfection

The KGN cells (cat. No. CL-0603; Procell, Wuhan, China) were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a cell incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) at 37°C with 5% CO2. The siRNA targeting MALAT1 (si-MALAT1) and its negative control (si-NC), as well as the miR-155-5p inhibitor and its corresponding control (Ctrl inhibitor), were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Suzhou, China). Cells were seeded in 24-well plates, and si-MALAT1, miR-155-5p inhibitor or their respective controls were transfected into KGN cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (cat No. 11668030; Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 48 h, the transfected cells were collected for subsequent experiments.

CCK-8 method

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2,500 cells per well. Each experimental group included at least 3 replicates, along with control wells and blank wells containing culture medium only. On the 2nd day, 10 µL of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCL-8) working solution (cat. No. G1613; Sevicebio, Wuhan, China) was added to each well containing 90 µL of culture medium. The plates were then incubated for an additional 1.5 h in a cell incubator, after which the optical density (OD) values were measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader (MK; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Apoptosis analysis

After transfection, cells were collected and centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min at 4°C. Apoptosis was assessed using the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Kit (cat No. G1511; Servicebio). The binding buffer was precooled to 4°C and used to resuspend the cells at a density of 3 × 106 cells/mL. To each 100 µL of cell suspension, 5 µL of Annexin V-FITC and 5 µL of propidium iodide (PI) were added. After incubating in the dark at room temperature for 10 min, 400 µL of binding buffer was added. Cell apoptosis was then evaluated using a flow cytometer (CytoFlex; Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA).

RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted from the cell samples in each group using the TRIzol Kit (cat. No. R0016; Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Briefly, cells were lysed in TRIzol, followed by the addition of 100 µL of chloroform replacement (cat. No. G3014-01; Servicebio) to every 1 mL of RNA extraction mixture. After vortexing for 15 s, the mixture was left at room temperature for 5 min and then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The upper colorless aqueous phase was carefully transferred to new centrifuge tubes, and total RNA was precipitated using isopropanol. Subsequently, 75% ethanol was added to remove residual salts and isopropanol. The RNA pellet was dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. The concentration and purity of total RNA were measured with ultraviolet spectrophotometry at A260.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction

The BeyoFast™ SYBR Green One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (cat. No. D7268S; Beyotime) was used to measure the relative expression of MALAT1, with GAPDH as the internal reference, using total RNA as the template. According to the manufacturer’s protocol, a 20 μL reaction system was prepared for each well in a 96-well plate, consisting of 10 µL SYBR Green One-Step Reaction Buffer (×2), 2 µL Enzyme Mix (×10), 2 µL Primer Mix (3 μM each), 2 μL RNA template, and RNase-free water to a final volume of 20 μL. The reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) cycling conditions were set as follows: reverse transcription at 50°C for 30 min, pre-denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 15–30 s. Primers used in this study were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and included the following sequences:

MALAT1 Forward (F):

5’-GCTCTGTGGTGTGGGATTGA-3’;

MALAT1 Reverse (R):

5’-GTGGCAAAATGGCGGACTTT-3’;

GAPDH Forward (F):

5’-GGTGGTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACA-3’;

GAPDH Reverse (R):

5’-CCAAATTCGTTGTCATACCAGGAAATG-3’.

For miR-155-5p, the RT-qPCR analysis was performed using the miRNA 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (by stem-loop) (cat. No. MR101-01; Vazyme, Beijing, China) and the miRNA Unimodal SYBR qPCR Master Mix Kit (cat. No. MQ102-C1; Vazyme), with U6 as the internal reference. The cDNA synthesis reaction system included 10 µL RNA template, 1 µL RT primer (2 µM), 2 µL RT Mix, 2 µL HiScript II Enzyme Mix, and RNase-free ddH2O to the final volume. The reaction was carried out under the following conditions: 25°C for 5 min, 50°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 min. The RT primer used for miR-155-5p was 5’-GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACAACCCC-3’. The qPCR primers for miR-155-5p were:

Forward (F): 5’-CGCGTTAATGCTAATCGTGATA-3’;

Reverse (R): 5’-AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT-3’.

The qPCR reaction system consisted of 10 µL 2× miRNA Unimodal SYBR qPCR Master Mix, 0.4 µL forward primer, 0.4 µL reverse primer, 2 µL cDNA template, and RNase-free ddH2O to the final volume. The qPCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s. Relative expression levels were analyzed using the 2–ΔΔCT method in Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA).

Western blot

Total proteins were extracted using RIPA with supplementation of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) on ice (cat. No. P0013B; Beyotime). The protein concentration was determined using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Bioss, Beijing, China). Then 5 × loading buffer was added and the protein samples were boiled for 20 min. Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) method was used to separate the proteins. The proteins on the gel were then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST) was used to dilute the skim milk to 5%, which was then used to block the membranes for 1 h at 37°C. The primary antibodies were diluted using TBST at 1:1,000, which included the anti-GPX4 (cat. No. bs-3884R; Bioss), anti-SLC7A11(cat. No. bs-6883R; Bioss) and anti-PAK2 (cat. No. 19979-1-AP; Proteintech, Wuhan, China). The anti-GAPDH was diluted at 1:10,000 (cat. No. bs-10900R; Bioss). The primary antibodies were used to incubate the membranes for 1 h at 37°C. TBST was used to wash the membranes for 3 times, 5 min each time. The secondary antibody (cat. No. AB0101; Abways, Shanghai, China) was diluted at 1 : 20,000 using TBST and was used to incubate the membranes for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed using TBST 3 times, 8 min each time. The eclectrochemiluminescence (ECL) kit was applied onto the membranes, and the immunoblotting image was taken on an ECL imaging machine (Servicebio). ImageJ (National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, USA) was used to analyze the grey values.

Dual-luciferase reporter gene assays

Plasmids containing the wild-type and mutant sequences of MALAT1 (MALAT1-wt, MALAT1-mt) and PAK2 (PAK2-wt, PAK2-mt) were constructed using the pmiRGLO vector (Promega, Madison, USA). The KGN cells were transfected with MALAT1-wt/mt or PAK2-wt/mt along with either the miR-155-5p inhibitor or control inhibitor using Lipofectamine 2000. The Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (cat. No. RG028; Beyotime) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions, and dual luciferase activity was measured using a laboratory luminometer.

Analysis of MDA and GSH/GSSG ratios

The MDA Kit (cat. No. S0131S; Beyotime) and the GSH/GSSG Ratio Detection Kit (cat. No. S0053; Beyotime) were used following the standard procedures provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were measured colorimetrically at 532 nm using a laboratory spectrophotometer, according to the product instructions. Total glutathione levels and reduced glutathione (GSH) levels were measured on a microplate reader at 405 nm. Oxidized GSH levels were calculated by subtracting the measured GSH levels from the total glutathione levels.

Statistical analyses

A non-normal distribution was assumed due to the small sample size. Briefly, the statistical significance of differences was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc analysis for multiple group comparisons and the Mann–Whitney U test for two-group comparisons, performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). Statistical analysis results were presented in the supplementary tables. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Basic calculations, including relative expression levels, protein expression, and luciferase activity, were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp.). Figures were generated using GraphPad, with triplicate data displayed as scatter plots showing the median and range. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Downregulation of MALAT1 is associated with increased apoptosis and ferroptosis in KGN cells

We confirmed using RT-qPCR that MALAT1 expression was significantly reduced in KGN cells transfected with siRNA targeting MALAT1, showing a fold change (Fc) of 0.320 ±0.040 (Figure 1A). Downregulation of MALAT1 reduced cell viability and induced apoptosis in KGN cells (Figure 1B–E). Additionally, MALAT1 knockdown increased MDA content and decreased the GSH/GSSG ratio in KGN cells (Figure 2A,B).

Western blot analysis was performed to assess changes in the relative protein expression levels of the anti-ferroptosis markers SLC7A11 and GPX4. The results showed that knockdown of MALAT1 significantly inhibited the expression of both SLC7A11 and GPX4 in KGN cells (Figure 2C–E). Taken together, these findings indicate that MALAT1 knockdown induces both apoptosis and ferroptosis while reducing cell viability in KGN cells. Furthermore, MALAT1 was found to modulate PAK2 expression in KGN cells by competitively acting as a molecular sponge for miR-155-5p. Bioinformatic analysis using the StarBase online database predicted the binding sites between MALAT1/PAK2 and miR-155-5p (Figure 3A,B). Based on the predicted binding sites, pmiRGLO plasmids containing MALAT1-wt/mt and PAK2-wt/mt were constructed. Dual-luciferase activity assays were performed after KGN cells were transfected with MALAT1-wt/mt or PAK2-wt/mt along with either the miR-155-5p inhibitor or control inhibitor. The results revealed that relative luciferase activity was significantly enhanced in cells transfected with MALAT1-wt and miR-155-5p inhibitor (Figure 3C) and was similarly increased in cells transfected with PAK2-wt and miR-155-5p inhibitor (Figure 3D). These findings verified the direct binding interactions between MALAT1/PAK2 and miR-155-5p in KGN cells. Furthermore, downregulation of MALAT1 in KGN cells led to a significant increase in miR-155-5p expression (fold change, 2.39 ±0.22; Figure 3E). Inhibition of miR-155-5p increased PAK2 mRNA expression (fold change, 1.94 ±0.15; Figure 3F) as well as PAK2 protein levels (Figure 4B). The mRNA expression level of PAK2 was suppressed by MALAT1 knockdown (fold change, 0.49 ±0.05) but was restored by co-treatment with the miR-155-5p inhibitor (fold change, 0.92 ±0.07) in KGN cells (Figure 4A. Similarly, MALAT1 knockdown reduced PAK2 protein levels, which were reversed upon miR-155-5p inhibition (Figure 4A,C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that MALAT1 regulates PAK2 expression by competitively binding to miR-155-5p.

miR-155-5p downregulation enhances cell viability and inhibits apoptosis and ferroptosis

Inhibition of miR-155-5p significantly increased cell viability and reduced apoptosis in KGN cells (Figure 5). Additionally, downregulation of miR-155-5p decreased MDA content, increased the GSH/GSSG ratio, and elevated the protein expression levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 in KGN cells (Figure 6), suggesting that miR-155-5p downregulation also reduces ferroptosis in KGN cells.

Downregulation of miR-155-5p reverses the impacts of MALAT1 knockdown in KGN cells

As described above, knockdown of MALAT1 reduced cell viability and induced apoptosis and ferroptosis in KGN cells. We further validated that inhibition of miR-155-5p could reverse the effects of MALAT1 knockdown in these cells (Figure 7). Specifically, the reduction in cell viability caused by MALAT1 knockdown was restored by miR-155-5p downregulation (Figure 7A), and the increase in apoptosis induced by MALAT1 knockdown was reversed by miR-155-5p inhibition (Figure 7B–E). The increase in MDA content induced by MALAT1 knockdown was reversed by miR-155-5p inhibition (Figure 8A). Similarly, the reductions in the GSH/GSSG ratio and the relative protein expression levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 caused by MALAT1 knockdown in KGN cells were restored by downregulation of miR-155-5p (Figure 8B–E). These findings demonstrate that miR-155-5p inhibition can effectively reverse the impacts of MALAT1 knockdown in KGN cells.

Discussion

The significance of this study lies in its investigation of MALAT1’s role in regulating apoptosis and ferroptosis in KGN cells, providing new insights into the pathophysiology of PCOS. Prior research has shown that MALAT1 downregulation is associated with increased apoptosis and decreased proliferation in GCs, contributing to ovary dysfunction in PCOS.15, 21 Abnormal GC death, particularly through apoptosis, has been identified as a key factor driving disrupted folliculogenesis in PCOS, ultimately leading to anovulation and infertility.22 Ferroptosis, a relatively newly characterized form of programmed cell death distinct from apoptosis, is marked by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation.21, 23 In recent years, studies have found that ferroptosis-related genes are dysregulated in GCs from PCOS patients and that inhibition of ferroptosis can alleviate PCOS symptoms in animal models.7, 21 Interestingly, another study reported that MALAT1 knockdown promotes ferroptosis in ectopic endometrial stromal cells in endometriosis, suggesting a potential connection between MALAT1 and ferroptosis regulation.24

In PCOS, ferroptosis-related genes have been linked to impaired oocyte quality.25 Enhanced ferroptosis in ovarian GCs from PCOS patients is associated with oocyte dysmaturity, increasing the risk of infertility.26 GPX4 acts as a key antioxidant regulator of ferroptosis by reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and enhancing cellular resistance to ferroptosis.27 Additionally, GSH is synthesized from cysteine via the System Xc– (comprising SLC7A11 and SLC3A2) and the transsulfuration pathway, with GSH consumption leading to GPX4 inactivation.28 SLC7A11, an upstream modulator of ferroptosis, inhibits lipid peroxidation accumulation and protects cells from ferroptosis by increasing cysteine availability and facilitating GSH synthesis.29

Recent studies have begun exploring ferroptosis-related regulatory mechanisms in PCOS using both cell and animal models. For example, PPAR-α has been shown to inhibit ferroptosis in GCs by interacting with FADS2, reducing MDA levels, and increasing GSH and GPX4 expression.23 miR-93-5p has been identified as a potential target in PCOS, as it can promote apoptosis and ferroptosis in GCs.30, 31 However, to date, no studies have specifically examined the role of MALAT1 in ferroptosis regulation within the context of PCOS. In this study, we demonstrated that downregulation of MALAT1 in KGN cells reduces GSH, GPX4 and SLC7A11 levels, thereby promoting ferroptosis. This reveals a previously uncharacterized ferroptosis-related function of MALAT1 in the pathophysiology of PCOS in vitro. Furthermore, our research builds on previous findings by elucidating a novel MALAT1/miR-155-5p/PAK2 regulatory axis in KGN cells, expanding the understanding of MALAT1’s role as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA). While the ceRNA function of MALAT1 has been established in various biological contexts, e.g., sponging miR-211-5p to regulate FOXO3 in H2O2-induced GCs,32 regulating the MALAT1/miR-212-5p/MyD88 axis in osteoarthritis,33 and controlling the MALAT1/miR-216a-5p/FOXA1 pathway in prostate cancer,34 our study is the first to report MALAT1’s modulation of miR-155-5p and its downstream effects on PAK2 in KGN cells.

Previous studies have shown that miR-155-5p is differentially expressed in follicular fluid exosomes from PCOS patients and is involved in glycolysis-related pathways in KGN cells, potentially influencing cell proliferation and apoptosis.20 Additionally, PAK2 has been shown to upregulate PKM2, a key glycolysis indicator, thereby mediating cell proliferation.30 In the context of PCOS, PAK2 has been implicated in regulating KGN cell apoptosis and proliferation via the β-catenin/c-Myc/PKM2 signaling pathway.19, 35 PAK2 regulates glycolytic processes and cell proliferation through the β-catenin/c-Myc/PKM2 signaling pathway in PCOS, underscoring the importance of altered glucose metabolism in the pathological mechanisms driving PCOS development.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Obtained in vitro, our findings may not fully capture the complex conditions within the ovary environment in vivo, limiting their direct applicability to PCOS. Additionally, while we examined apoptosis and ferroptosis, other cell death pathways, such as autophagy, might also play roles in GC dysfunction. Lastly, the absence of clinical validation means the relevance of MALAT1 as a therapeutic target remains uncertain. Future studies should use in vivo models and patient samples to confirm these results.

Conclusions

This study reveals that MALAT1 regulates apoptosis and ferroptosis in KGN cells through the miR-155-5p/PAK2 pathway, providing new insights into GC dysfunction in PCOS. Our findings highlight MALAT1 as a potential therapeutic target, suggesting that targeting the MALAT1/miR-155-5p/PAK2 axis could mitigate cellular damage in PCOS. Further research in animal models and clinical settings is needed to validate these findings and explore MALAT1’s potential as a treatment target.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14872220. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Mann–Whitney U test results.

Supplementary Table 2. Results of Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-v2.jpg)

.jpg)

-v3.jpg)