Abstract

Background. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the 6th most common cancer worldwide and claims roughly 700,000 lives each year; nearly 50% of global HCC fatalities occur in China.

Objectives. To conduct a comprehensive meta-analysis identifying predictors of sorafenib efficacy in combination with thermal ablation for HCC treatment.

Materials and methods. A comprehensive literature search was conducted up to October 2024, reviewing 720 identified studies. From these, 19 studies were selected that included a total of 3,341 participants with HCC at baseline. The meta-analysis examined the effects of sorafenib in combination with physical thermal ablation, using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Analyses were performed using two-sided methods and either fixed-effect or random-effects models, depending on the level of heterogeneity.

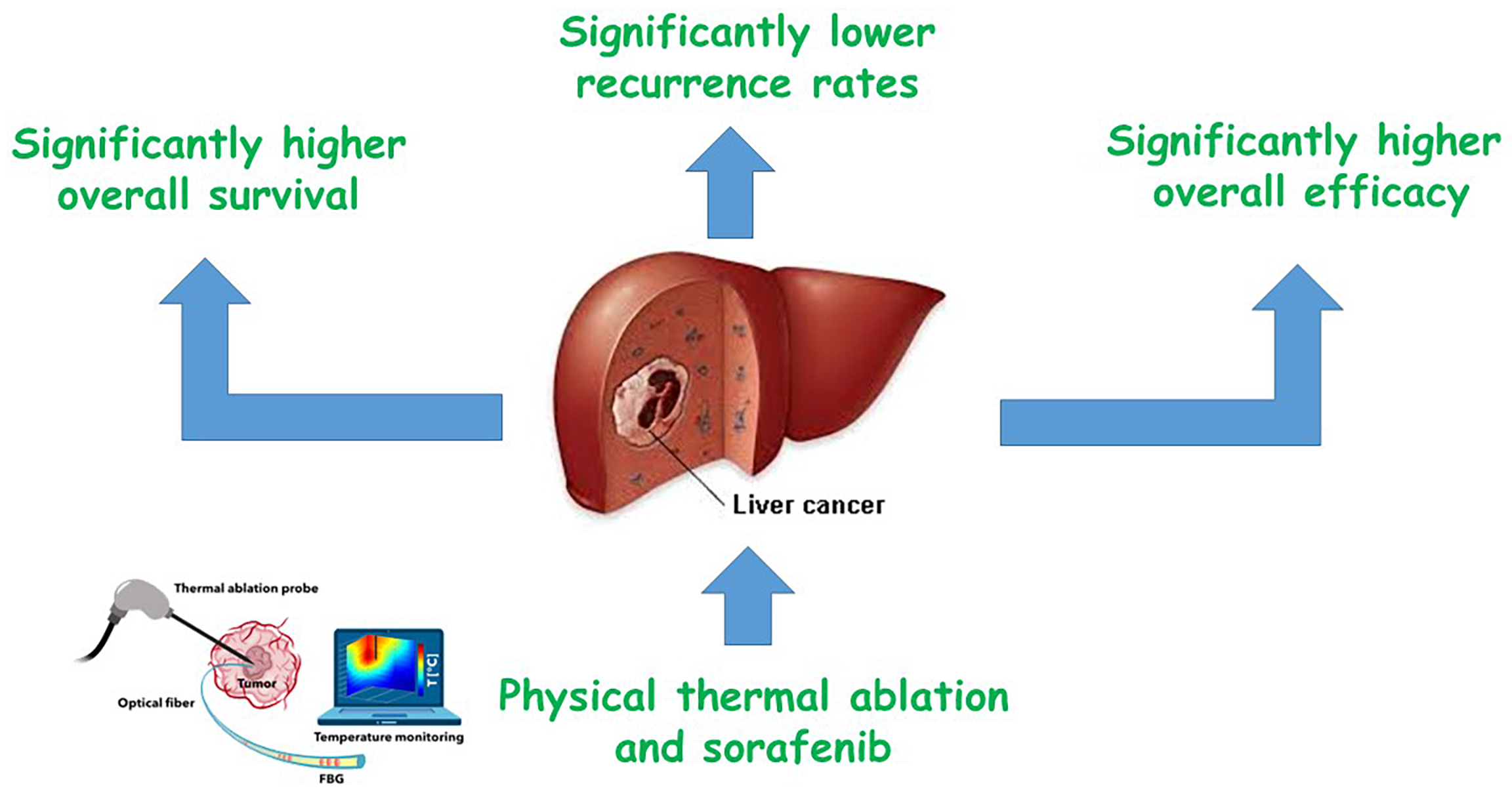

Results. The meta-analysis revealed that combining physical thermal ablation with sorafenib significantly improved outcomes in HCC patients: Overall survival (OS) was more than doubled (OR = 2.03; 95% CI: 1.55–2.67; p < 0.001), recurrence rates were significantly reduced (OR = 0.62; 95% CI: 0.39–0.98; p = 0.04), and overall treatment efficacy was markedly higher (OR = 2.53; 95% CI: 1.61–3.96; p < 0.001) compared with thermal ablation alone.

Conclusions. In individuals with HCC, physical thermal ablation and sorafenib had significantly higher OS, lower recurrence rates, and high overall efficacy compared to physical thermal ablation. To validate this discovery, more research is needed, and caution must be implemented when interacting with its values.

Key words: hepatocellular carcinoma, sorafenib, overall survival, physical thermal ablation, overall efficacy

Background

Globally, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks as the 6th most common malignant tumor. Each year, approx. 700,000 people die from HCC worldwide, with China accounting for nearly half of these deaths.1, 2 Current primary treatment options include liver transplantation, surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation, percutaneous ethanol injection, transarterial chemoembolization, and sorafenib.3 Advances in medical technology and the development of various prognostic scoring systems, such as the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system and the Italian Liver Cancer (ITA.LI.CA) tumor staging system, have expanded the range of treatment options available to HCC patients.4 Although surgical resection is considered the first-line treatment for HCC, factors such as multiple lesions, unfavorable tumor location, and poor patient condition can render surgery unfeasible.5

Because the early symptoms of liver cancer are often subtle or absent, many patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, missing the optimal window for surgical intervention. The widespread use of liver transplantation is further limited by its high cost and the scarcity of available donor organs. As a result, physical thermal ablation has emerged as a less invasive and effective alternative therapy. Microwave ablation and radiofrequency ablation are the 2 main forms of physical thermal ablation used for liver tumors. Although they rely on different physical principles, both techniques utilize imaging guidance to accurately target the tumor and insert electrodes into the tissue. When the tumor tissue reaches a certain temperature, protein denaturation occurs, leading to tumor destruction and shrinkage. Xu et al. conducted a meta-analysis comparing the effects of radiofrequency ablation and hepatic resection in the treatment of liver cancer.6 The study found that, compared to the hepatic resection group, the radiofrequency ablation group had similar 1-year overall survival (OS), lower 5-year OS, a higher incidence of overall recurrence, shorter hospitalization duration, and a lower complication rate. This suggests that thermal ablation offers the advantages of a shorter treatment time and fewer complications compared to surgery. However, patients with HCC who undergo thermal ablation alone often face poor long-term prognosis and high recurrence rates.7 Sorafenib, a multi-targeted kinase inhibitor, addresses some of these challenges by inhibiting key components of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling cascade, including B-Raf, Raf-1 and other kinases, thereby suppressing tumor cell growth and differentiation.8 Additionally, by blocking receptors such as hepatocyte cytokine receptors (e.g., c-Kit), vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (e.g., VEGFR-2), and platelet-derived growth factor receptors (e.g., PDGFR-β), sorafenib reduces angiogenesis.9

According to a meta-analysis of 1,462 patients with advanced HCC, sorafenib reduced the risk of tumor progression and death while improving the disease control rate compared to placebo.10 Numerous studies have also demonstrated that sorafenib, whether used alone or in combination with other treatments, can extend the survival time of patients with HCC.11, 12, 13 However, sorafenib may also have adverse effects on normal liver tissue and can delay tissue healing following thermal ablation. Therefore, when considering both the positive and negative effects of sorafenib’s therapeutic action, the overall benefit of combining it with physical thermal ablation must be carefully balanced. Meta-analysis, by synthesizing disaggregated data, can provide a higher level of evidence to inform therapeutic decision-making.14

Objectives

We conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of sorafenib combined with physical thermal ablation in the treatment of HCC.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

For the purpose of creating a summary, the investigations demonstrating the effectiveness of sorafenib in combination with physical thermal ablation for the treatment of HCC were chosen.15

Information sources

Figure 1 represents the study selection process. Literature was included when the following inclusion criteria were met16, 17:1) The study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), observational, prospective, or retrospective in design; 2) The participants had been diagnosed with HCC; 3) The intervention included combination therapy with physical thermal ablation and sorafenib; 4) The study specifically evaluated the effectiveness of sorafenib combined with physical thermal ablation for HCC.

Studies were excluded if they did not assess the effectiveness of this combination therapy, focused solely on physical thermal ablation, or lacked meaningful comparative significance.18, 19

Search strategy

A search protocol was established using the PICOS framework, defined as follows: the population (P) consisted of individuals with HCC; the intervention or exposure (I) was combination therapy with sorafenib and physical thermal ablation; the comparison (C) involved comparing the combination therapy to physical thermal ablation alone; the outcomes (O) included OS, recurrence rates and overall efficacy; and the study design (S) was unrestricted, with no limitations placed on study type.20

A thorough search of the Google Scholar, Embase, Cochrane Library, PubMed, and OVID databases was conducted through October 2024, using a predefined set of keywords and additional terms, as detailed in Table 1.21, 22 To avoid including studies that did not establish a clear link between the effectiveness of sorafenib combined with physical thermal ablation for HCC, duplicate records were removed. The remaining articles were compiled into an EndNote file (Clarivate, London, UK), and their titles and abstracts were reassessed for relevance.23, 24

Selection process

The meta-analysis method was then used to organize and assess the process that followed the epidemiological proclamation.25, 26

Data collection process

Some of the criteria used for data extraction included the name of the first author, study details, year of publication, country or region, population type, study categories, quantitative and qualitative assessment methods, data sources, outcome measures, clinical and therapeutic characteristics, and statistical analysis approaches.27

Data items

When a study yielded differing values, data related to the evaluation of the effectiveness of sorafenib combined with physical thermal ablation for HCC were independently extracted.

Research risk of bias assessment

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies and evaluated the quality of the methodologies employed in the papers selected for further analysis. An unbiased review of the methods used in each study was conducted by both authors.

Effect measures

Sensitivity analysis was limited to studies that assessed and documented the effectiveness of sorafenib in combination with physical thermal ablation for HCC.

Synthesis methods

Using a dichotomous approach and a random or fixed-effect model, the odds ratio (OR) and a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were determined. A range of 0–100% was used to determine the I2 index. Heterogeneity was assessed, with thresholds of 0%, 25%, 50%, and 75% indicating no, low, moderate, and substantial heterogeneity, respectively.28 To ensure that the exact model was used, additional structures that show a high degree of similarity with the related inquiry were also examined. The random effect was used.28 A subclass analysis was performed by splitting the original estimation into the previously specified consequence groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was utilized in the analysis to define the statistical significance of differences across subcategories.

Reporting bias assessment

Both quantitative and qualitative methods were employed to measure the bias in the investigations: the Egger’s regression test and funnel plots, which display the logarithm of the ORs against their standard errors (SEs). The presence of investigation bias was determined by p ≥ 0.05.29

Certainty assessment

Each p-value was assessed using two-tailed testing. Graphs and statistical analyses were generated using Review Manager v. 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

Out of 720 identified studies, 19 papers published between 2011 and 2024 met the inclusion criteria and were selected for this analysis.30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 Table 2 presents the findings of these studies. At baseline, the combined studies included a total of 3,341 participants with HCC, with individual study sample sizes ranging from 30 to 1,114 subjects.

As illustrated in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, in individuals with HCC, combination therapy demonstrated significantly higher OS (OR = 2.03; 95% CI: 1.55–2.67; p < 0.001) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 57%), lower recurrence rates (OR = 0.62; 95% CI: 0.39–0.98; p = 0.04) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 75%), and greater overall efficacy (OR = 2.53; 95% CI: 1.61–3.96; p < 0.001) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 44%), compared to physical thermal ablation alone.

Due to insufficient data on variables such as age, ethnicity and gender, the application of stratified models to investigate the effects of specific factors was not possible. Using both the quantitative Egger’s regression test and visual inspection of the funnel plots, no evidence of publication bias was detected (p = 0.89, 0.87 and 0.91, respectively), as shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7. However, it was noted that there was no evidence of selective reporting bias, although the majority of the included RCTs exhibited poor technical quality.

Discussions

A total of 3,341 HCC participants were included at baseline across the studies selected for this meta-analysis.30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 In individuals with HCC, combination therapy demonstrated significantly higher OS, lower recurrence rates, and greater overall efficacy compared to physical thermal ablation alone. However, further studies are required to confirm these findings, and caution should be exercised when interpreting their significance, as they may affect the robustness and reliability of the reported outcomes. .49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59

Chemotherapy and ablation have been employed extensively in the treatment of cancer, including advanced renal cell carcinoma and small cell lung cancer.60, 61 Physical thermal ablation has the benefits of minimal damage, rapid recovery and repeated application in the treatment of HCC. However, the lesion’s size and the presence of heat dissipation make full ablation challenging and increase the chance of local recurrence. Recurrence is more likely when the tumor’s diameter exceeds 3.0 cm.62, 63 Therefore, the goal of therapy improvement is to lower the rate of tumor recurrence following thermal ablation. Radiofrequency ablation combined with sorafenib achieves greater efficacy and survival, prolongs the radiofrequency interval, and reduces recurrence rates.

It has been demonstrated that radiofrequency ablation and the kinase inhibitor sorafenib work in concert. Its role in tumors is to suppress angiogenesis, which lowers heat loss and indirectly improves ablation. Additionally, sorafenib itself prevents the growth and development of tumor cells. Millions of people have benefited from the first-line therapy of liver cancer with sorafenib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks several receptors, including RAF-1, VEGFR-2 and FLT-3.11 According to studies, sorafenib may cause capillary damage and VEGF and PDGF inhibition as the mechanism of hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR). Direct pressure on the hands and feet causes the vessels to become mechanically injured once more, which causes an inflammatory reaction and the development of blisters.64 As is well known, serious side effects might result in treatment suspension and ultimately impact the patient’s ability to survive. Studies have also indicated that diarrhea is a predictor of improved OS in individuals with HCC using sorafenib.64, 65 According to Reig et al., a higher chance of survival was linked to the occurrence of dermatological side effects within 60 days of starting sorafenib.66 The quality of life may be impacted, and the anti-tumor efficacy may be limited if the adverse reaction results in a dose adjustment or interruption of sorafenib, regardless of whether it has a direct impact on survival. Therefore, to increase the lifespan and quality of life for patients with HCC, sorafenib dose adjustments and standardized treatment are required.

Not all of the studies included in this meta-analysis were RCTs. The number of original publications was limited, and the retrospective cohort studies were subject to recall and selection biases. Furthermore, the majority of the study populations were Chinese, with only a small proportion of Japanese and Spanish participants, making the overall study cohort racially non-representative and limiting generalizability. Notably, HCC is the 2nd most common cause of cancer-related mortality in China, after lung cancer, with China accounting for approx. 27% of global cancer deaths.67

China now has the highest prevalence of liver cancer (about 55% of the global total rate) and the highest number of fatalities due to hepatitis B virus infection, aflatoxin exposure, alcohol misuse, and environmental pollution.68 The fact that the majority of the research participants in this meta-analysis were Chinese may be due in large part to the fact that China still has a long way to go in reducing the incidence and mortality of liver cancer. The heterogeneity of other parameters was noteworthy, with the exception of radiofrequency interval and overall efficacy. Variations in sample size, tumor characteristics (size and number), patient age, and prior treatment history may account for these differences. The effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation in conjunction with sorafenib in patients with HCC has also been meta-analyzed by Chen et al.69

The best treatment for HCC is still being investigated. According to a thorough comparative study of HCC scoring systems published in the World Journal of Hepatology, a customized approach for patients with HCC should be created, and the appropriate scoring system should be chosen based on the patient’s circumstances.4 Whether a treatment is curative, palliative, or a combination of both, as in this study (radiofrequency ablation + sorafenib), depends on the patient’s characteristics and liver function. Thus, the development of a treatment plan for HCC requires the integration of several fields, including oncology, interventional radiology, and hepatobiliary surgery. Depending on the patient’s development, side effects, and complications, customized settings and modifications would be required at any moment. In the treatment of HCC, physical thermal ablation in conjunction with sorafenib is superior to radiofrequency ablation or microwave ablation alone, per the present meta-analysis. Patients receiving combination therapy should be regularly monitored for adverse effects. Despite the use of random-effects models and subgroup analysis in this investigation, the reliability of the findings may still be impacted by study heterogeneity. More high-caliber research is still required to prove that physical thermal ablation plus sorafenib is superior than physical thermal ablation alone.

Limitations

Nevertheless, the excluded studies did not meet the necessary standards to be incorporated into the meta-analysis. Moreover, we did not have enough information to determine whether factors such as race, sex and age had an impact on results. Bias may have increased as a result of the incorporation of incomplete or erroneous data from earlier studies. The individuals’ age, gender, nutrition and race were likely sources of bias in addition to their nutritional status. Unintentionally skewed values might arise from incomplete data and unpublished research.

Conclusions

In individuals with HCC, combination therapy demonstrated significantly higher OS, lower recurrence rates, and greater overall efficacy compared to physical thermal ablation. Further research is needed to confirm these findings, and caution should be taken when interpreting their significance. Further exploration of this issue would have an impact on the significant of the evaluated assessments.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)