Abstract

Background. Stroke is a leading cause of disability and one of the primary causes of death worldwide. Stroke survivors often experience a range of symptoms, including impaired motor function, speech and language abnormalities, swallowing difficulties, cognitive deficits, visual disturbances, and sensory impairments.

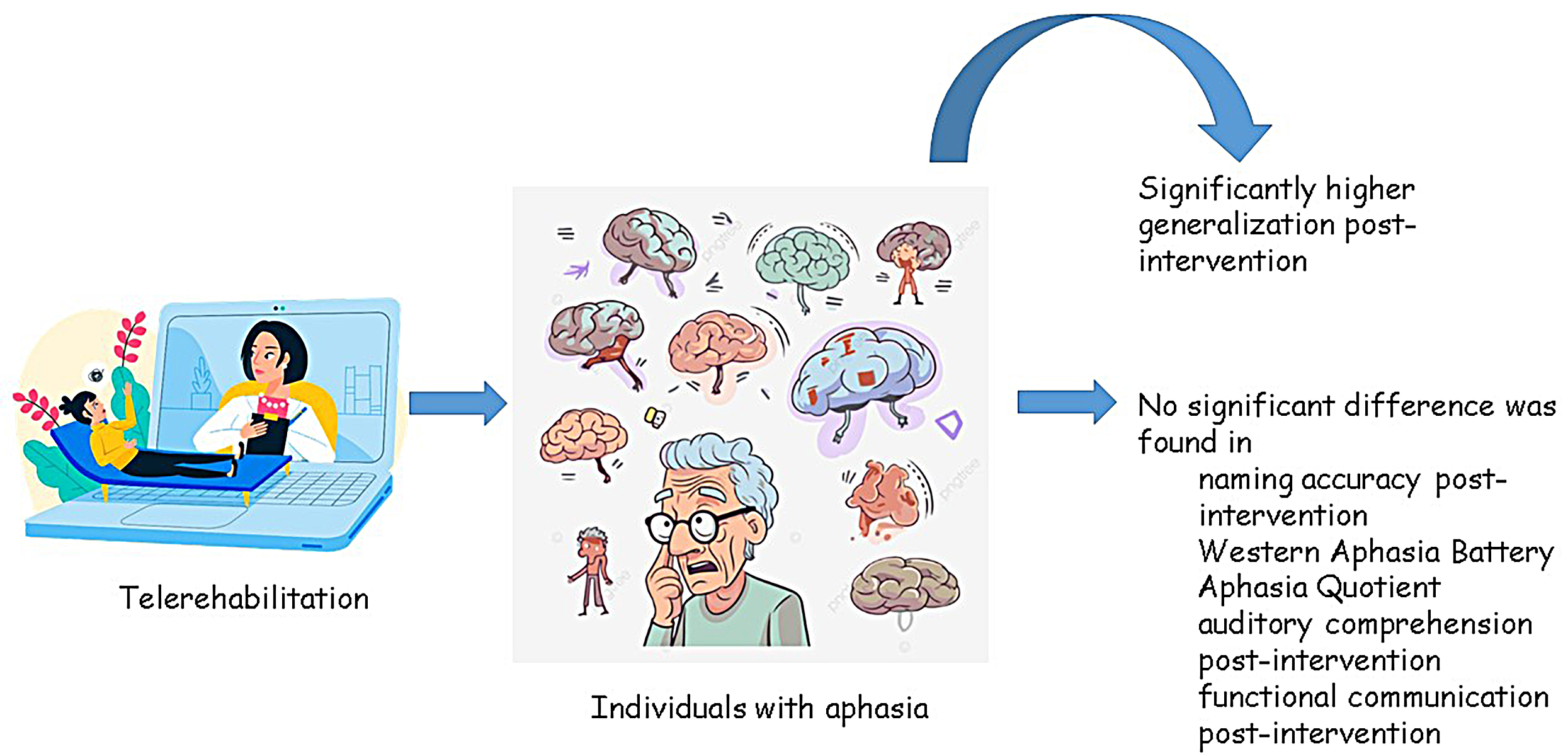

Objectives. This meta-analysis was conducted to assess and compare the relative effectiveness of telerehabilitation compared to traditional in-person speech and language therapy for individuals with aphasia.

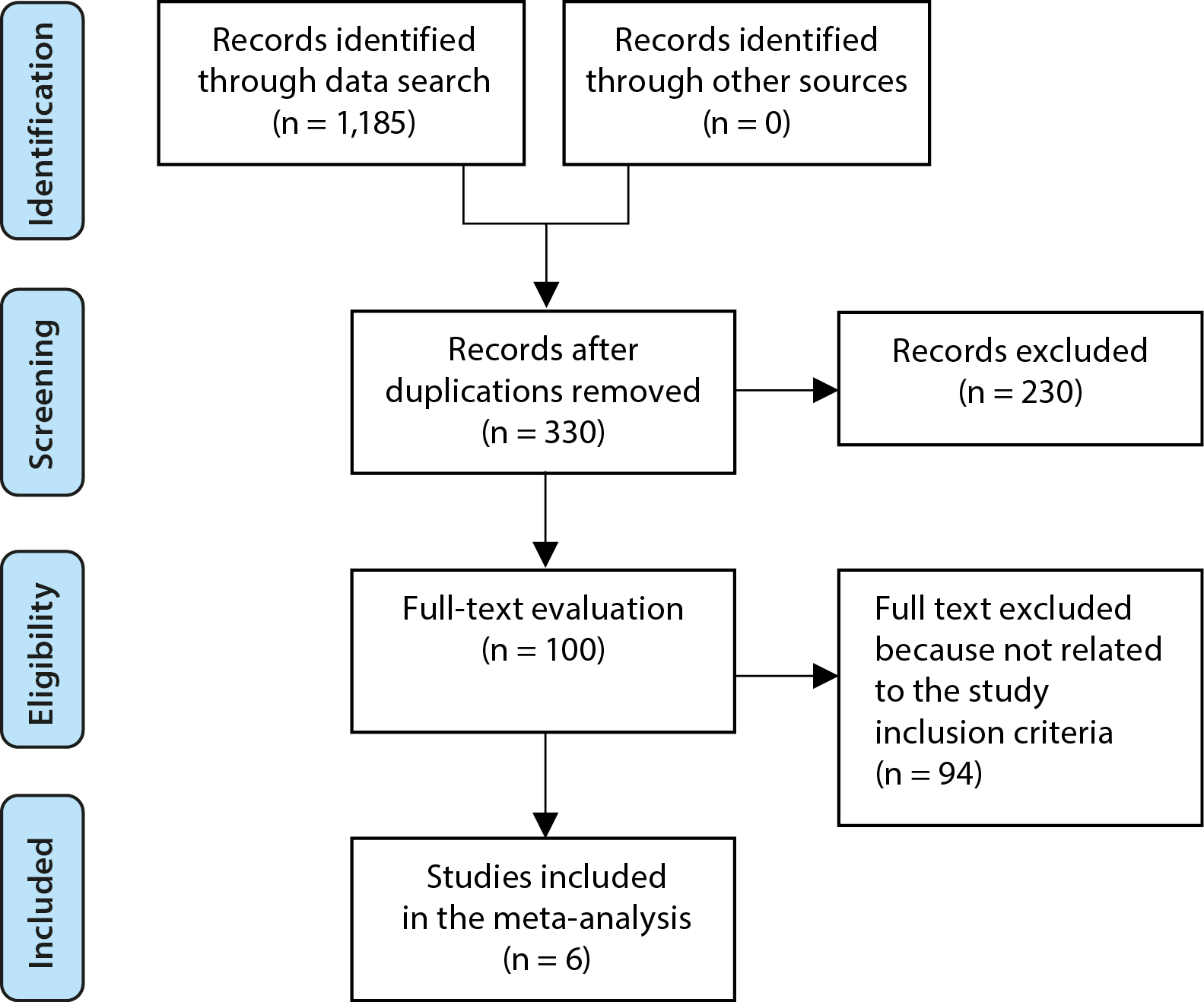

Materials and methods. A comprehensive literature search was conducted up to October 2024, reviewing 1,185 identified studies. Ultimately, 6 studies were selected that included a total of 168 participants with aphasia at baseline. The meta-analysis examined the relative effectiveness of telerehabilitation compared to traditional in-person speech and language therapy using continuous outcomes, with mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) calculated. Analyses were performed using either fixed-effect or random-effects models, depending on heterogeneity.

Results. In individuals with aphasia, telerehabilitation demonstrated significantly greater improvements in generalization post-intervention compared to face-to-face treatment (MD = 11.53; 95% CI: 3.64–19.43; p = 0.004). However, no significant differences were found between telerehabilitation and face-to-face treatment in naming accuracy post-intervention (MD = 3.09; 95% CI: 1.98–8.16; p = 0.23), Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) aphasia quotient (MD = –0.54; 95% CI: –9.96–8.88; p = 0.91), auditory comprehension post-intervention (MD = 0.66; 95% CI: –8.83–10.14; p = 0.89), or functional communication post-intervention (MD = –0.95; 95% CI: –10.19–8.29; p = 0.84).

Conclusions. In individuals with aphasia, telerehabilitation showed significantly greater improvements in generalization post-intervention compared to face-to-face treatment. However, no significant differences were observed between the 2 approaches in naming accuracy, WAB aphasia quotient, auditory comprehension, or functional communication post-intervention. To validate these findings, further research is needed, and caution should be exercised when interpreting the current results due to the limited number of included studies.

Key words: aphasia, telerehabilitation, generalization post-intervention, Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) aphasia quotient, face-to-face treatment

Background

Stroke is a leading cause of disability and one of the leading causes of death globally.1 Stroke survivors frequently have a variety of symptoms, such as reduced motor functions, speech abnormalities, swallowing issues, cognitive deficits, vision impairment, and sensory disturbances.2 Aphasia affects about 1/3 of stroke patients.3 Communication problems brought on by aphasia frequently prevent patients and caregivers from engaging in social activities. People with aphasia have a number of deficits in some or all language modalities that can affect speech production and/or comprehension, reading and/or writing, and gesture.4 Word-finding difficulties are a sign of mild aphasia, while significant impairment of all language modalities is a sign of global aphasia.5 Research indicates that even years after the beginning of aphasia, people might still benefit from rehabilitation programs. However, only some obtain self-tailored treatment, and when they do, it is usually limited to the first few months post-stroke.4 Within the first 5 years following the incident, nearly half of stroke survivors express dissatisfaction with the absence of social or clinical assistance.6 Stroke survivors, particularly those in rural areas, have limited access to long-term rehabilitation. One of the additional factors is that individuals with brain damage frequently have several comorbidities, which makes it more challenging for them to get to a rehabilitation facility.7 Howe et al. investigated the contextual factors that prevent persons with aphasia from engaging in social activities. Individuals with aphasia believed that social integration was hampered by the absence of services following hospital-based speech treatment and the inability to interact with other aphasics. Participants also mentioned having trouble traveling to and from social settings.8 Given all of these restrictions, it is vital to offer therapies that guarantee aphasia patients’ ongoing care in order to improve their social engagement. Therefore, cutting-edge telecommunications technology appear to be the answer to this problem.

The provision of rehabilitation services through information and communication technology is known as telerehabilitation.9 Its main goals is to decrease inpatient hospital stays and boost community services, such as rehabilitation after hospital ward discharge. Assessment, monitoring, prevention, intervention, supervision, education, consultation, and counseling are some of the specific services that can be included in telerehabilitation. These services are intended to assist people with impairments.10

Objectives

This study aimed to use a meta-analysis to evaluate the relative effectiveness of telerehabilitation compared to traditional in-person speech and language therapy for individuals with aphasia.11

Methods

Information sources

Figure 1 summarizes the overall study framework. Studies were incorporated when they met the following inclusion criteria12, 13: 1) The study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), observational study, prospective study, or retrospective study; 2) The participants included individuals diagnosed with aphasia; 3) Telerehabilitation was integrated as part of the intervention; 4) The study compared the effects of telerehabilitation with traditional in-person speech and language therapy in individuals with aphasia.

Studies were excluded if they did not assess the relative effectiveness of telerehabilitation compared to traditional in-person speech and language treatment, focused solely on face-to-face interventions, or lacked meaningful comparative significance.14, 15

Search strategy

A search protocol was developed using the PICOS framework, defined as follows: the population (P) consisted of patients with aphasia; the intervention (I) was telerehabilitation; the comparison (C) involved comparing telerehabilitation to face-to-face treatment; the outcomes (O) included generalization post-intervention, naming accuracy post-intervention, and Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) Aphasia Quotient scores; and the study design (S) was unrestricted, with no limitations on study type.16

A thorough search was conducted across the databases Google Scholar, Embase, the Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Ovid up to October 2024, using a set of keywords and additional terms as outlined in Table 1.17, 18 To avoid including studies that did not address the relative effectiveness of telerehabilitation compared to traditional in-person speech and language therapy for individuals with aphasia, duplicate records were removed. The remaining articles were compiled into an EndNote file (Clarivate, London, UK), and their titles and abstracts were re-assessed for relevance.19, 20

Selection process

The meta-analysis method was subsequently used to organize and assess the process in accordance with established epidemiological guidelines.21, 22

Data collection process

The data collection process included the following criteria: authors’ names, study details, year of publication, country or region, population type, study categories, quantitative and qualitative assessment methods, data sources, outcome measures, clinical and therapeutic characteristics, and statistical analysis approaches.23

Data items

When a study yielded multiple values, data related to the evaluation of the relative effectiveness of telerehabilitation compared to traditional in-person speech and language therapy for individuals with aphasia were independently extracted.

Research risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in the selected studies and the quality of the methods used were carefully assessed. The methodology of each study was objectively reviewed to ensure consistency and rigor.

Effect measures

Sensitivity analysis was restricted to studies that assessed and documented the relative effectiveness of telerehabilitation compared to traditional in-person speech and language therapy for individuals with aphasia. A subgroup analysis was conducted to compare the correlation between telerehabilitation and traditional in-person treatment across different patient variables, examining the sensitivity within aphasia subgroups.

Statistical analyses

Using a conservative approach and a random-effects model, the mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. The I2 index was employed to assess heterogeneity, with values ranging from 0 to 100%; thresholds of 0%, 25%, 50%, and 75% indicated no, low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.24 To ensure that the appropriate model was applied, additional structures demonstrating a high degree of similarity to the relevant inquiry were also examined.24 Subgroup analysis was conducted by dividing the original estimates into the predefined outcome groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to determine the statistical significance of differences across subcategories.

Reporting bias assessment

Both quantitative and qualitative methods were employed to assess bias in the included studies. The Egger regression test and funnel plots, which plot the logarithm of the odds ratios (ORs) against their standard errors (SEs), were utilized. The presence of publication bias was determined using a threshold of p ≥ 0.05.25

Certainty assessment

Two-tailed tests were applied to examine each p-value. Review Manager v. 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to perform the statistical analyses and generate the graphs.

Results

Out of 1,185 identified studies, 6 papers published between 2014 and 2021 met the inclusion criteria and were selected for this meta-analysis.7, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 The findings from these studies are summarized in Table 2. At baseline, the included studies collectively involved 168 participants with aphasia. The sample sizes of the selected studies ranged from 10 to 40 subjects.

As illustrated in Figure 2, telerehabilitation resulted in significantly greater generalization post-intervention in individuals with aphasia (MD = 11.53; 95% CI: 3.64–19.43; p = 0.004), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), compared to face-to-face treatment. However, no significant differences were observed between telerehabilitation and face-to-face treatment in naming accuracy post-intervention (MD = 3.09; 95% CI: 1.98–8.16; p = 0.23; I2 = 0%), WAB (MD = –0.54; 95% CI: –9.96–8.88; p = 0.91; I2 = 0%), auditory comprehension aphasia quotient post-intervention (MD = 0.66; 95% CI: –8.83–10.14; p = 0.89; I2 = 0%), or functional communication post-intervention (MD = –0.95; 95% CI: –10.19–8.29; p = 0.84; I2 = 0%), as shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6.

The use of stratified models to examine the effects of specific variables was not possible due to the lack of detailed data on factors such as age, gender, severity, and ethnicity in the comparison outcomes. No indication of publication bias was detected based on visual interpretation of the funnel plots or the quantitative Egger regression tests (p = 0.87, 0.88, 0.89, 0.86, and 0.85, respectively), as shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9. Nonetheless, it was noted that most of the included RCTs exhibited suboptimal technical quality, although no evidence of selective reporting bias was identified.

Discussions

The meta-analysis included 6 studies, which collectively involved 168 participants with aphasia at baseline.7, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 In individuals with aphasia, telerehabilitation showed significantly greater generalization post-intervention compared to face-to-face treatment. However, no significant differences were found between telerehabilitation and face-to-face treatment in naming accuracy post-intervention, WAB aphasia quotient, auditory comprehension post-intervention, or functional communication post-intervention. Further research is needed to confirm these findings, and caution should be exercised when interpreting the results, as many of the comparisons were based on a small number of included studies, which may impact the statistical significance and robustness of the assessments.31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41

The validity and reliability of telerehabilitation systems for speech and language disorders are increasingly supported by evidence. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of telepractice in the evaluation of acquired language disorders42 and in the treatment of these conditions,43 particularly regarding speech and voice impairments in individuals with Parkinson’s disease.44 Additionally, telerehabilitation has shown promise in addressing fluency disorders, with multiple studies reporting that telerehabilitation is both feasible and effective, leading to positive clinical outcomes in the treatment of stuttering in children,45 adolescents46 and adults.47 However, the effectiveness of telerehabilitation applications specifically targeting aphasic impairments – such as telerehabilitation for anomia48 or the evaluation of apraxia of speech49 – remains poorly supported and requires further investigation.50

Agostini et al. demonstrated the feasibility and efficacy of telerehabilitation for addressing lexical deficiencies in chronic stroke patients by showing comparable outcomes between in-person and telerehabilitation settings.7 Additionally, Latimer et al. reported that computer-based therapy may reduce the societal costs associated with managing health services for individuals with chronic aphasia.51 The rationale for telerehabilitation lies in its ability to activate mechanisms similar to those engaged in traditional therapies.52 Initial findings from clinical practice suggest that telerehabilitation is well-suited for speech and language therapy and can be effectively applied to lexical retrieval training. For example, interacting with a touchscreen can replicate many of the same therapeutic processes as writing on paper.

Two technological strategies show promise for delivering remote speech and language therapy. The 1st approach, known as asynchronous telerehabilitation, involves self-administered, computer-based activities that allow patients to complete structured training independently, without requiring the immediate presence of a speech-language pathologist. Therapists can later review the patient’s progress and adjust the complexity of the exercises based on individual needs.53 Kurland et al. demonstrated that for individuals with chronic aphasia, unsupervised home practice combined with weekly video teleconferencing support was effective.54

The 2nd approach, known as synchronous telerehabilitation, uses two-way videoconferencing, allowing the speech-language pathologist to be present in real time. This method enables therapists to provide live remote treatments while reducing the time and financial burden associated with travel.28

The currently available research indicates that the topic of speech and language telerehabilitation has not been adequately explored through meta-analyses. While telerehabilitation appears to be an acceptable mode of service delivery for individuals with motor impairments following stroke – showing comparable effectiveness to in-person therapy52 – such results have not yet been consistently confirmed for individuals with aphasia. To advance therapeutic practice, it is essential to incorporate emerging evidence on the application of telerehabilitation in aphasia treatment. Despite an extensive search strategy, only 6 trials out of 1,185 identified studies met the inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis.

There is a clear need for further research in this field, as the selected studies suggest that speech and language telerehabilitation is a relatively new approach to aphasia rehabilitation, with the potential for significant improvements. However, because all included studies involved small sample sizes, future research with larger cohorts is necessary to generate more robust and compelling evidence. Additionally, inadequate reporting and a lack of clarification from study authors often made it difficult to determine the risk of bias. For example, Zhou et al. reported that patients were randomly assigned to either the training or control group, but they did not provide details about the randomization process.27

Additionally, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) revealed that the methodological quality of the included studies ranged from extremely low-to-moderate, making it impossible to draw definitive conclusions about the efficacy of telerehabilitation compared to traditional in-person treatment. The certainty assessments were significantly influenced by issues related to indirectness of evidence and risk of bias. Specifically, the quality of evidence was downgraded due to unclear or inadequate methods for patient randomization in RCTs, the nonrandomized allocation of participants between groups, and the lack of reported details on allocation concealment.

Additionally, in accordance with the Core Outcome Set for aphasia research proposed by Wallace et al., evaluations related to the indirectness of evidence were downgraded by 1 level for all outcomes except the WAB.55 This downgrade stems from the use of surrogate outcome measures – defined as measures used in place of a true clinical endpoint – since most tests assessing language abilities were conducted within standardized language evaluation settings rather than within natural communication contexts.56

Successful communication depends on having language and communication abilities that enable the conveyance of messages through spoken, written, nonverbal, or combined modalities. Formal measures of communication success range from analyzing real-world discourse interactions to sampling conversations during specific activities.4 As previously noted by Brady et al., surrogate outcome measures of communicative and linguistic abilities are often employed as formal assessments of receptive and expressive language, typically using standardized language tests. This reliance is largely due to the lack of comprehensive, reliable, valid, and internationally accepted tools for evaluating communication in naturalistic settings.4

Due to the considerable variation observed in the results, for which no reasonable explanation could be identified, the certainty rating for the generalization outcome was also downgraded by 1 level for inconsistency. These findings highlight the need for further research and will likely have a significant impact on the ability to predict the treatment’s overall effectiveness. As a result, additional high-quality RCTs, as well as data on the cost-effectiveness of telerehabilitation, are needed to strengthen future research in speech and language telerehabilitation. Although the search strategy included 6 databases and considered studies published in conference proceedings, the grey literature was not explored. In cases where information appeared incomplete or missing, the authors were contacted; however, no responses were received.

Limitations

Although 1,185 studies were initially screened, only 6 ultimately met the inclusion criteria, comprising a total sample size of 168 participants. This small sample size may limit the generalizability and statistical power of the findings. Additionally, the quality of the included studies was uneven, with several methodological flaws that could affect the reliability and validity of the results. Furthermore, inconsistencies in participant characteristics – such as age, gender and cultural background – across the included studies may further limit the external validity and applicability of the conclusions.

Telerehabilitation showed significant improvements in generalization post-intervention; however, no significant differences were observed in naming accuracy, auditory comprehension, or functional communication, which may limit its broader clinical applicability. Additionally, the article does not provide data on the long-term effects of telerehabilitation, making it impossible to evaluate its sustained effectiveness in long-term rehabilitation. Furthermore, the comparison between telerehabilitation and face-to-face treatment did not fully account for specific implementation details or individual patient differences, which may affect the interpretation and applicability of the results.

Conclusions

In individuals with aphasia, telerehabilitation demonstrated significantly greater generalization post-intervention compared to face-to-face treatment. However, no significant differences were observed between telerehabilitation and face-to-face treatment regarding naming accuracy post-intervention, WAB aphasia quotient, auditory comprehension post-intervention, or functional communication post-intervention. Further research is needed to confirm these findings, and caution is warranted when interpreting the results, as many comparisons were based on a limited number of included studies. This limitation may impact the strength and significance of the assessed outcomes.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)