Abstract

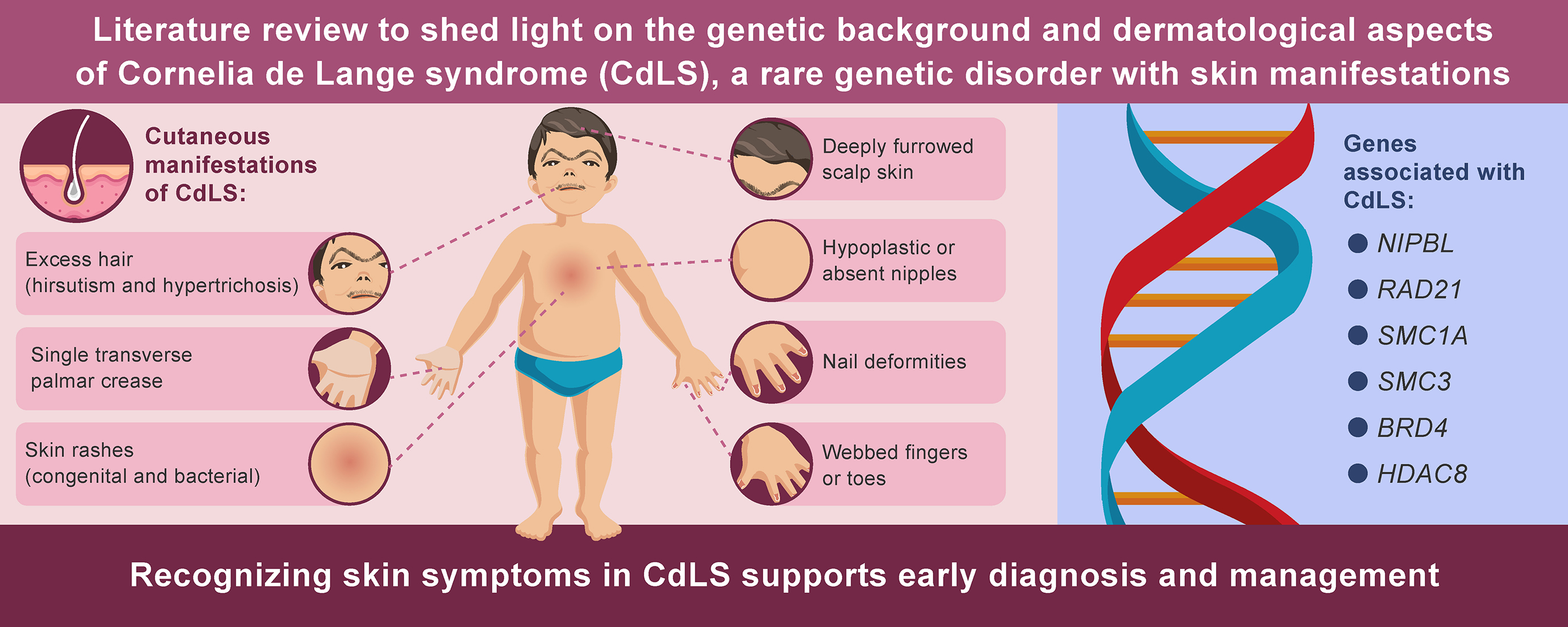

Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS) is a complex genetic disorder affecting multiple body systems. It is characterized by distinctive facial features, skeletal anomalies, neurological and developmental impairments, physiological cutaneous manifestations such as hirsutism and synophrys, and numerous other signs and symptoms. Among affected individuals, the clinical presentation of CdLS varies widely, ranging from relatively mild to severe forms. Additionally, CdLS increases the frequency of certain dermatoses, including cutaneous bacterial infections and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Six genes have been identified in association with CdLS: NIPBL (Nipped-B-like protein), RAD21 (double-strand break repair protein rad21 homolog), SMC1A and SMC3 (structural maintenance of chromosomes 1A and 3), BRD4 (bromodomain-containing protein 4), and HDAC8 (histone deacetylase 8). Cornelia de Lange syndrome is estimated to occur in 1 out of every 10,000–30,000 live births, making it a rare condition and posing diagnostic challenges due to its low incidence. The present review aims to raise awareness of CdLS among dermatologists by providing a brief overview of the syndrome and summarizing the current literature on its dermatological manifestations.

Key words: dermatology, genetics, pediatrics

Introduction

Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS) is an uncommon and complicated genetic illness characterized by unusual facial traits, developmental delays, limb abnormalities, and several systemic abnormalities.1, 2 Cornelia de Lange Syndrome, initially recognized by Brachmann in 1916 and later named by Cornelia de Lange in 1933, affects approx. 1 in every 10,000–30,000 live births.3, 4 The disorder has been related to genetic differences in the cohesin complex, particularly mutations in 6 genes: NIPBL, RAD21, SMC1A, SMC3, BRD4, and HDAC8.5, 6, 7 These genes play critical roles in chromatin organization, gene expression, and DNA repair. This underscores the causes of the effects of CdLS on various physiological systems.7, 8 Despite their potential relevance for diagnosis and therapeutic management, the dermatological aspects of CdLS have received limited attention in recent research, creating a vacuum in our understanding of the wide range of clinical symptoms of this condition.

Previous research has primarily focused on the developmental, neurological and systemic features of the disease, with dermatological symptoms being highlighted as secondary findings. In the early 1960s and 1970s, investigators described the physical characteristics associated with CdLS, including hirsutism – specifically referring to excessive male-pattern hair growth in women – and hypertrichosis, which describes excessive hair growth in any area, regardless of pattern or gender.

In CdLS, both conditions may be present, with hypertrichosis being more common.9, 10 This study established a framework for understanding the dermatological features of CdLS, although this was constrained by the diagnostic tools available at the time. Additional studies have helped us understand the genetic foundation and clinical presentation of CdLS. A groundbreaking research by Krantz et al. and Tonkin et al. identified NIPBL as the first gene related to CdLS.11, 12

Unfortunately, there is a conspicuous lack of thorough and up-to-date research on dermatological signs of CdLS. While some studies have examined skin symptoms, including cutis marmorata telangiectatic congenita and abnormal dermatoglyphics, studies on the dermatological characteristics of patients with CdLS are limited.13, 14 Kline et al. conducted a detailed clinical examination of CdLS; however, their primary focus was not on its dermatological aspects.15 The absence of expertise in this field is especially concerning, because skin symptoms can be pivotal for detecting uncommon genetic disorders and impact treatment and general wellbeing of the patients.

New research highlighted the varied appearances of CdLS, underlining the significance of recognizing milder versions of the disorder.16 Boyle et al. provided valuable insights into the incidence of self-injurious behaviors in CdLS, which might influence the skin.2 However, previous studies have not adequately examined the numerous skin symptoms observed in people with CdLS.

Objectives

The objectives of this work are to provide an overview of CdLS and to recognize its cutaneous manifestations.

Methods

Our literature search was conducted using PubMed, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases, spanning from 1963 to May 2022. All photographs presented in this manuscript are from the authors’ own clinical collections and were obtained with appropriate patient consent. The primary search term used in the literature review was “CdLS.”A literature review identified all studies that addressed the clinical features of CdLS. All studies discussing the dermatological aspects of this syndrome were selected. Publications discussing the genetic background of this syndrome were also included.

Review

Overview of CdLS

Cornelia de Lange syndrome is a developmental multisystem disorder with variable physical, cognitive, and behavioral characteristics.17 This prevalence is probably underestimated, because milder or atypical cases may not have been diagnosed. This syndrome affects both genders equally.18

Clinical case illustration

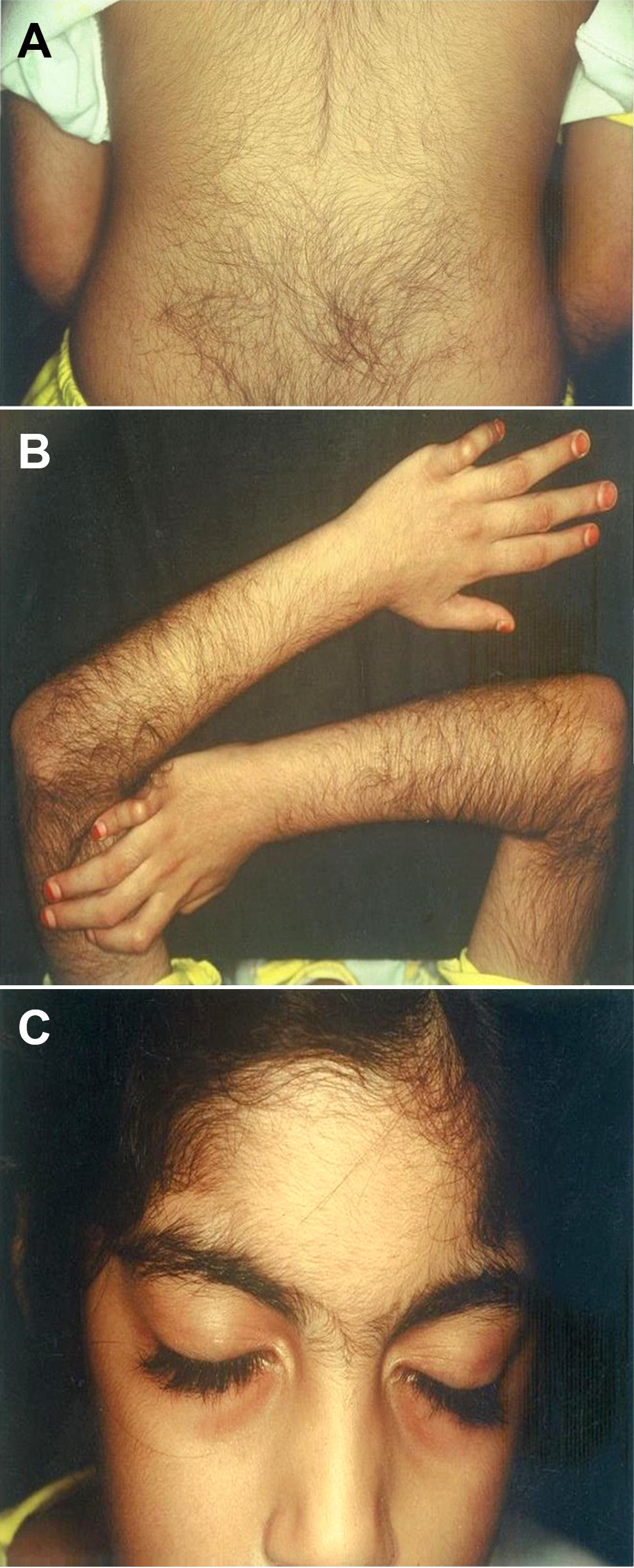

A 6-year-old female patients presented with characteristic facial features, including synophrys and long eyelashes, accompanied by generalized hypertrichosis. The patient showed a low anterior hairline with thick, dark hair and distinctive facial features, including arched eyebrows that met in the midline (synophrys). Generalized hypertrichosis was noted, particularly prominent on the back and extremities. Initial dermatological examination led to suspicion of CdLS, which was subsequently confirmed through genetic testing. This case illustrates how recognition of characteristic dermatological features can facilitate early diagnosis of CdLS.

Genetic background

The etiology of CdLS has been elucidated through molecular investigations of genetic variants affecting the cohesin complex. To date, 6 genes have been implicated: nipped-B-like protein (NIPBL), double-strand break repair protein rad21 homolog (RAD21), structural maintenance of chromosomes 1A (SMC1A) and 3 (SMC3), bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4), and histone deacetylase 8 (HDAC8).. Mutations in the NIPBL gene were associated with 50–60% of cases.17

The cohesin complex and its associated regulatory proteins help to contact sequence elements and regulate gene expression. In addition to gene expression regulation, the cohesin complex plays a role in sister chromatid cohesion and DNA damage signaling and repair.17

Cornelia de Lange syndrome has an autosomal dominant familial or X-linked pattern of inheritance. Nonetheless, most cases result from de novo heterozygous mutations in patients with no family history of CdLS.17

Classification

Cornelia de Lange syndrome can be categorized into 3 types based on clinical variability. Type I, the classic form, is characterized by distinctive facial features and significant skeletal abnormalities. Type II, the mild form, presents with typical facial features accompanied by milder skeletal anomalies. Type III refers to cases where CdLS-like phenotypic manifestations are observed either in the presence of chromosomal aneuploidies or following teratogenic exposure. The classic features of CdLS include distinctive craniofacial characteristics, limb anomalies, growth retardation, and intellectual disability.. Additional features include cutaneous manifestations, gastrointestinal disorders, genitourinary malformations, and cardiovascular defects.17

Cutaneous manifestations of De Lange syndrome

Hirsutism and hypertrichosis

Hirsutism and hypertrichosis are prominent and typical features of CdLS, observed in most patients (80%).18 Although hirsutism does not necessarily require treatment, it may affect patients’ psychological wellbeing. Therefore, rather than the amount of hair growth, the subjective perception of the patient should be the deciding factor when determining whether the patient needs treatment.19

Hypertrichosis in CdLS is typically generalized, with particularly prominent involvement of the nape of the neck, the lateral aspects of the elbows, and the lower sacral area (Figure 1).20 Scalp hair is often characterized by low frontal hair implantation and a low posterior hairline, observed in approx. 92% of patients. Additionally, individuals with CdLS tend to have thick scalp hair that frequently extends into the temporal regions.2 Eyelashes are long and curly in 99% of patients (Figure 1).20 The eyebrows are neat, well-penciled, arched, and thick. Moreover, patients almost always have synophry, which is the fusion of the eyebrows above the bridge of the nose (Figure 2).21

Dark hair color

Cornelia de Lange syndrome tends to be associated with dark hair and eyebrows due to a disturbance in hair pigmentation (Figure 2). However, there has been no evidence of pigmentation disorders in the skin or eyes.21, 22

Cutis verticis gyrate

Cutis verticis gyrate is an overgrowth of the scalp skin, resulting in deep furrows and convoluted folds of the skin. Cutis verticis can be diagnosed clinically. Surgery is the definitive treatment for cutis verticis. However, appropriate scalp hygiene is important to avoid the accumulation of secretions (Figure 3).23 Cutis verticis gyrate has been reported in several patients with CdLS.24

Sweat gland abnormalities

Sweat gland density was reduced in 34% of the individuals with CdLS. Decreasing sweat gland density with age is normal; however, individuals with CdLS exhibit a reduction in size that exceeds typical age-related expectations.25

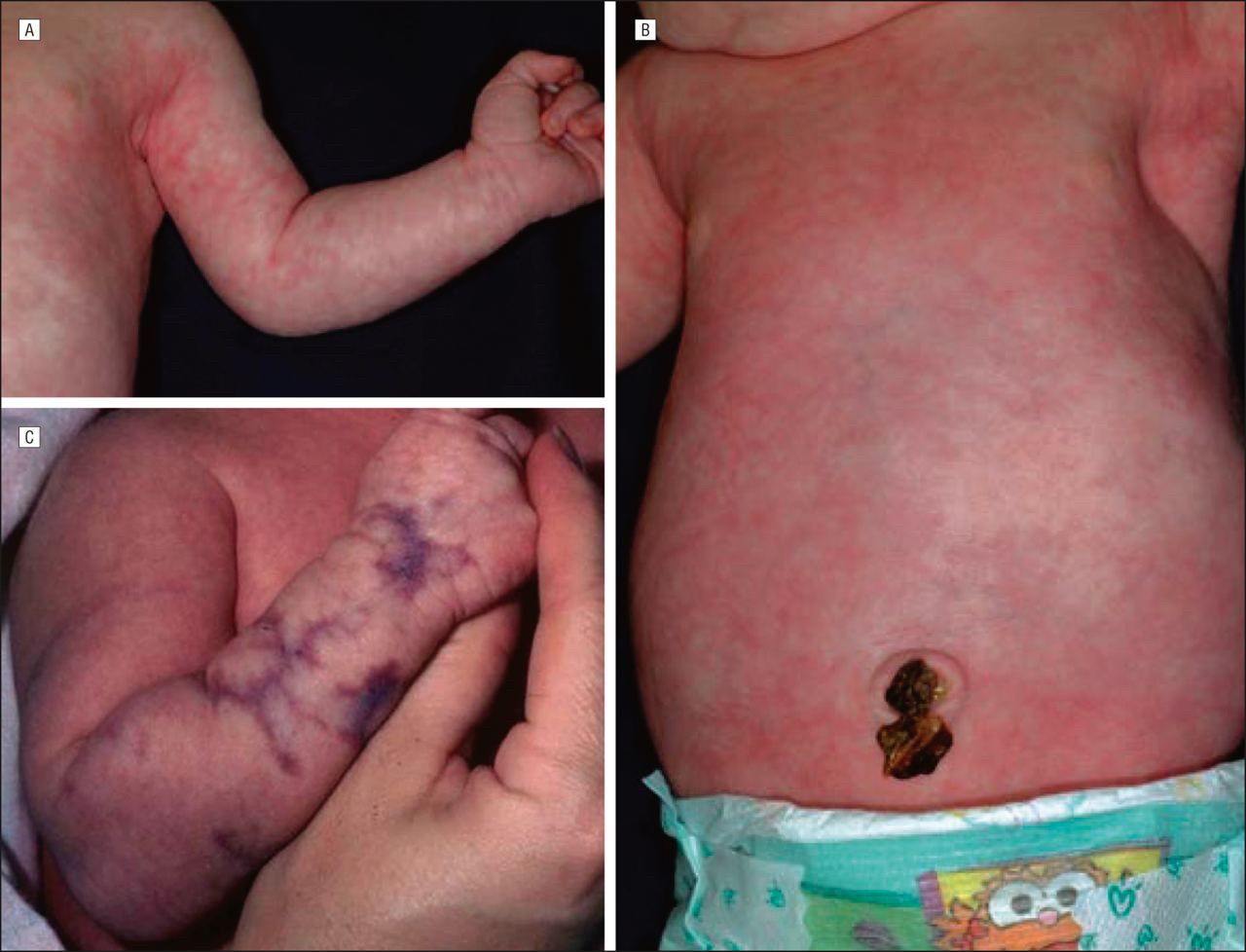

Cutis marmorata telangiectatic congenita

Cutis marmorata telangiectatic congenita (CMTC) is a rare congenital rash resulting from vascular malformations. It presents with fixed reticulate erythema, unlike physiological cutis marmorata, which resolves with skin warming. Cutis marmorata telangiectatic congenita is clinically diagnosed, but histopathological examination of the skin is insufficient for diagnosis. It is most associated with reticulate erythema, which is observed in persistent CdLS (Figure 4).10 CMTC shows a strong correlation with CdLS, as more than half of the patients with CdLS have CMTC.26

Nail abnormalities

Approximately 35% of patients with patients with CdLS had aplastic or hypoplastic nails (Figure 5).27, 28

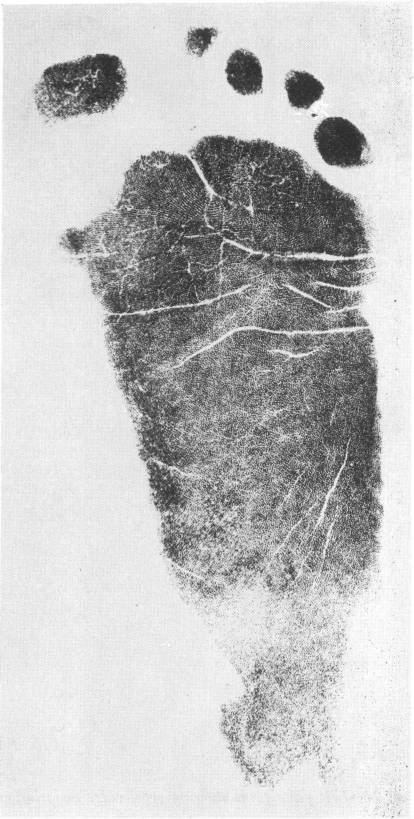

Abnormal dermatoglyphics

Patients with CdLS usually have abnormal epidermal ridge patterns, including a hypoplastic ridge pattern, which is characterized by ridges that are reduced in height. This is often accompanied by an excess of white lines on prints (Figure 6).13 Under these conditions, the ridges are short, curved and disorganized, instead of running neatly in parallel lines. Dotted ridges are also a type of ridge dissociation associated with CdLS.29

Crease anomalies

Many syndromes are associated with abnormal palmar creases, and CdLS is among them, with approx. 60% of patients exhibiting a single transverse palmar crease (Figure 7).28

Cutaneous syndactyly

Cutaneous syndactyly is a malformation that arises during limb development, characterized by the fusion of adjacent digits involving only the skin. Cutaneous syndactyly of the toes is illustrated in Figure 8.28, 30

Cutaneous bacterial infection

Due to CdLS-associated antibody deficiency and impaired T-cell function, a high frequency of recurrent infections has been reported, with bacterial skin infections occurring in approx. 4% of cases.31

Hypoplastic nipples and umbilicus

Hypoplastic nipples and the absence of nipples or the umbilicus have been observed in approx. 50% of patients, most commonly among individuals with classic CdLS (Figure 9).18, 32

Thrombocytopenia and its complications

Although thrombocytopenia in CdLS typically resolves over time, in some cases it may persist, leading to the development of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.18, 33

Self-injury and aggressive behaviors

Self-injury is common in individuals with CdLS, with roughly of them exhibiting clinically significant self-injury.18 This includes some behaviors that may concern dermatologists, including onychotillomania, trichotillomania and dermatillomania, which refer to the impulse or urge to pick or pull out nails, hair and skin, respectively.34 Parent management training (PMT) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are 2 effective interventions for these behavioral problems and are well supported in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Parent management training aims to improve family interactions through aggressive behaviors. The basic principle of PMT is that there is a direct relationship between aggressive behavior and the consequences that follow that behavior. Cognitive behavioral therapy aims to enhance social problem-solving skills, using techniques such as identifying patterns of anger expression, recognizing the consequences of self-injurious behavior, and reshaping aggressive reactions into more socially appropriate responses.35

Differential diagnosis

Several conditions may present with features resembling CdLS, including Fryns syndrome, Coffin–Siris syndrome, and Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome.1 Each of these conditions shares some dermatological features with CdLS but can be distinguished through careful clinical examination and genetic testing.1, 36

Impact on quality of life

The dermatological manifestations of CdLS can significantly impact patients’ psychosocial wellbeing. Visible features such as hirsutism and facial differences may affect self-image and social interactions. Support groups and psychological counseling should be considered as part of comprehensive care.37, 38

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, the available literature on the dermatological manifestations of Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS) is scarce, and most published studies focus primarily on systemic or developmental aspects. As a result, much of the dermatological evidence is derived from case reports or small case series, which may reduce the generalizability of the findings. Second, variability in diagnostic approaches and reporting styles across studies makes it difficult to establish precise prevalence rates of skin manifestations. Third, because this work was conducted as a narrative review rather than a systematic review, some relevant studies may not have been captured despite a broad database search. Finally, the rarity of CdLS itself and the frequent under-recognition of milder phenotypes may have led to underreporting of dermatological features in the literature.

Conclusions

This review achieves its stated aim of providing a comprehensive overview of CdLS and its cutaneous manifestations. Key findings include the high prevalence of hair abnormalities, the significance of cutaneous markers for diagnosis, and the importance of dermatological care in management. Future research should focus on genotype-phenotype correlations in skin manifestations, long-term outcomes of dermatological interventions, and impact of cutaneous features on quality of life.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.