Abstract

Background. Research documenting the results of liver trauma surgery revealed a connection between prophylactic drainage (PD) and escalating infections or septic consequences.

Objectives. Meta-analysis research was conducted to review the wound complications (WCs) frequency of PD in liver resections (LRs).

Materials and methods. Up until June 2024, comprehensive literature study was completed, and 757 related studies were reviewed. The 10 selected studies included 5,459 LRs at the beginning; 2,918 of them were drained and 2,541 were not. The dichotomous approaches and a fixed or random model were used to assess the WCs frequency of PD in LRs using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

Results. Prophylactic drainage had significantly higher surgical site wound infection rate (OR = 1.97; 95% CI: 1.09–3.55, p = 0.02) compared to non-PD in in LR patients, though no significant difference was found among PD and non-PD in LR patients in infected intra-abdominal collections (IIACs; OR = 3.17; 95% CI: 0.93–10.80, p = 0.07).

Conclusions. Prophylactic drainage had a considerably greater surgical site wound infection rate, and there was no discernible difference between IIACs and non-PD in LR individuals. Nevertheless, because there were not many studies nominated for comparison in the meta-analysis, care must be used when working with its outcomes, and further research is warranted to confirm these findings.

Key words: liver resections, prophylactic drainage, infected intra-abdominal collections, surgical site wound infection

Background

Franco et al. confirmed in 1989 that prophylactic drainage (PD) was not required following simple liver resections (LRs) and suggested a no-drainage treatment in elective LRs.1 Patients may experience an accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity, referred to as ascites. This may occur due to various factors, including elevated pressure in one of the primary hepatic blood arteries (portal vein).2 A physician can prescribe medications to alleviate fluid retention.

The predominant reason for a biliary drain is an obstruction or constriction (stricture) of a bile duct. This results in cholestasis, characterized by the deceleration or cessation of bile flow from the liver.3 Various disorders may lead to bile duct obstruction and cholestasis, including pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas). Abdominal drainage is a technique designed to remove fluid from the peritoneal cavity, the area between the abdominal wall and the organs.2 Traditionally, in patients undergoing hepatic resection, an abdominal drain is typically placed in the subphrenic or subhepatic space next to the resection surface. This facilitates the alleviation of intra-abdominal pressure caused by ascitic fluid accumulation and enables the observation of postoperative intra-abdominal hemorrhage, in addition to the identification and drainage of any bile leakage. Research documenting the results of liver trauma surgery revealed a connection among PD and escalating infections or septic consequences.2 Fang et al. found that there was no indication to support the usual utilization of PD in elective LRs in their meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comprising 465 persons.3 The studies included in that meta-analysis showed no significant variations in postoperative illness between patients with or without PD.3 Drainage after elective LRs is still frequently utilized in existing practice and appears to be more based on experience than on scientific research. A multi-institutional investigation of 1,041 persons found that 564 of them had drains put at the operator’s discretion, with a frequency of utilization of 54%. When compared to the non-drained cohort, the drained cohort showed higher rates of complications, bile leaks and 30-day readmissions.

Objectives

Our goal was to review the routine utilization of PD after LRs by reviewing the most recent research. To compare drained with non-drained patients, a meta-analysis was conducted with the aim to evaluate the wound complications (WCs) frequency of PD in LRs.

Materials and methods

We conducted a meta-analysis to assess studies demonstrating the frequency of WC in PD cases involving LR.4

Information sources

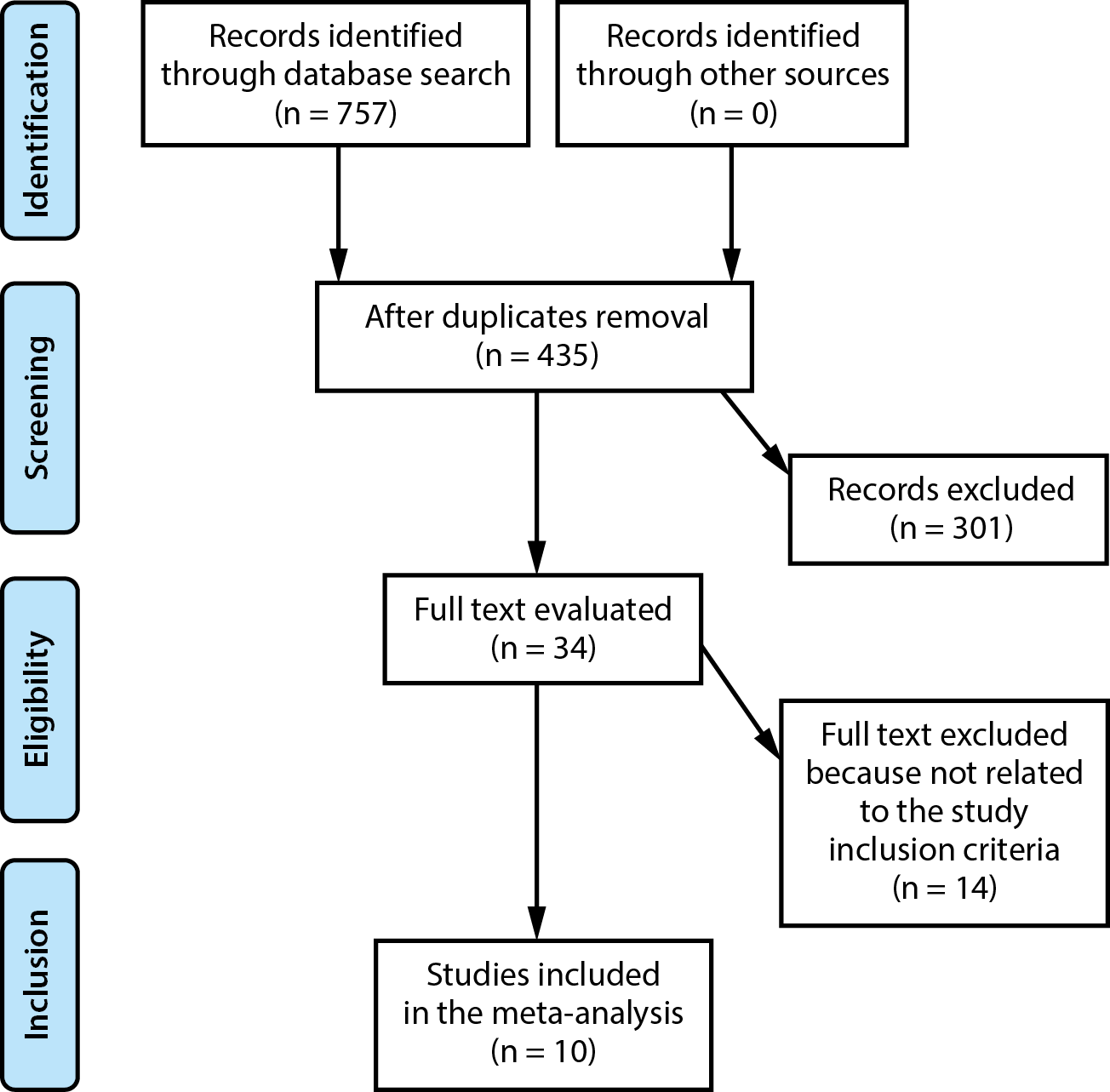

Figure 1 characterizes the study selection process. When the inclusion criteria were satisfied, the following literature was included in the study5, 6:

1. The investigation was prospective, observational, RCT, or retrospective research.

2. Persons with LRs were the investigated patients.

3. The intervention was PD.

4. The research appraised the effect of PD and non-PD in the management of LRs on surgical site wound infection (SSWI) and infected intra-abdominal collections (IIACs)

Studies that did not evaluate the effect of PD and non-PD in the management of LRs on SSWI and IIACs, and studies with no comparison were also excluded.7, 8, 9

Search strategy

Based on the PICOS approach, we identified a search protocol operation and described it as follows: PD was the “intervention” or “exposure”, SSWI and IIACs were the “outcome” and “research design”, and PD was the “population” for people with LRs. The planned research was not restricted in any way.10

A comprehensive literature search was conducted through June 2024 across the following databases: Google Scholar, Embase, Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Ovid. We used a keyword organization and additional keywords for LRs, PD, IIAC, and SSWI, as shown in Table 1. Duplicate records were removed, and the remaining studies were compiled into an EndNote library (Clarivate, London, UK). Titles and abstracts were re-evaluated to exclude studies unlikely to contribute meaningfully to the assessment of the association between the frequency of PD in LRs and WCs.11

Selection process

The procedure that followed the epidemiological announcement was then arranged and evaluated using the meta-analysis method.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Data collection process

The data collection criteria included authors’ names, study date and year, geographical location, population type, medical and treatment characteristics, study categories, methods of quantitative and qualitative assessment, data sources, outcome evaluation, and statistical analysis. When the study yielded different results, we separately gathered the data depended on an estimation of the WCs frequency of PD in LRs.

Research risk of bias assessment

We evaluated the methodology of the chosen publications to determine the potential for bias in each analyzed study. The technical quality was assessed utilizing the “risk of bias instrument” from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, v. 5.1.0.20 Each study was classified according to the assessment criteria and assigned a corresponding level of risk of bias. The research was classified as having a medium bias risk if 1 or more quality criteria were unmet and as having a low bias risk if all criteria were satisfied. The research was considered to have a substantial risk of bias if several quality requirements were either completely or partially met.

Effect estimates

Sensitivity analysis was restricted to studies that estimated and characterized the WCs frequency of PD in LRs. A subclass analysis was utilized to compare the sensitivity of LRs persons with and without PD.

Statistical analyses

A dichotomous approach was used, and either a random-effects or fixed-effects model was applied to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The I2 index was assessed on a scale from 0 to 100%. At 0%, 25%, 50%, and 75% of the data, there was no, low, moderate, and significant heterogeneity, respectively.21 To validate the suitability of the chosen model, additional frameworks were analyzed, focusing on those demonstrating a high degree of similarity among the included studies. The random effect model was utilized. A subgroup analysis was conducted by dividing the original estimation into the previously defined consequence groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 meant statistical significance of differences among subgroups.

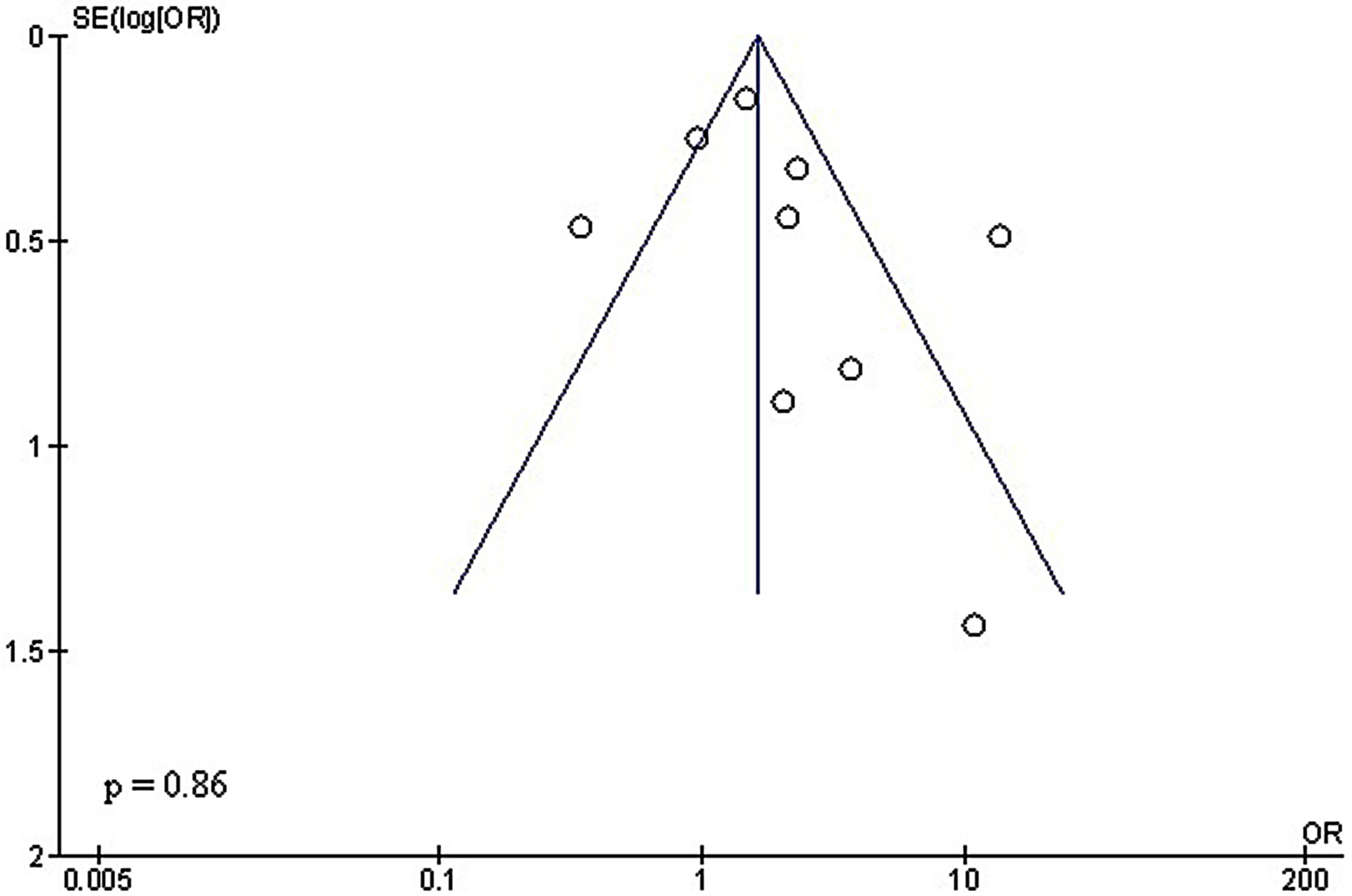

Reporting bias assessment

We employed Egger’s regression test and funnel plots – plotting the logarithm of the ORs against their standard errors (SEs) – to assess publication bias both quantitatively and visually. A p ≥ 0.05 was interpreted as indicative of no significant publication bias.22

Certainty assessment

Two-tailed testing was employed to analyze each p-value. Graphs and statistical analyses were generated utilizing Reviewer Manager (RevMan) v. 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

Out of 757 relevant studies that met the inclusion criteria, 10 papers published between 1993 and 2021 were selected for analysis.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The details of these studies are presented in Table 2. At the outset of the included research, a total of 5,459 LRs were analyzed, of which 2,918 were drained and 2,541 were not. The sample sizes of the individual studies ranged from 81 to 1,868 patients.

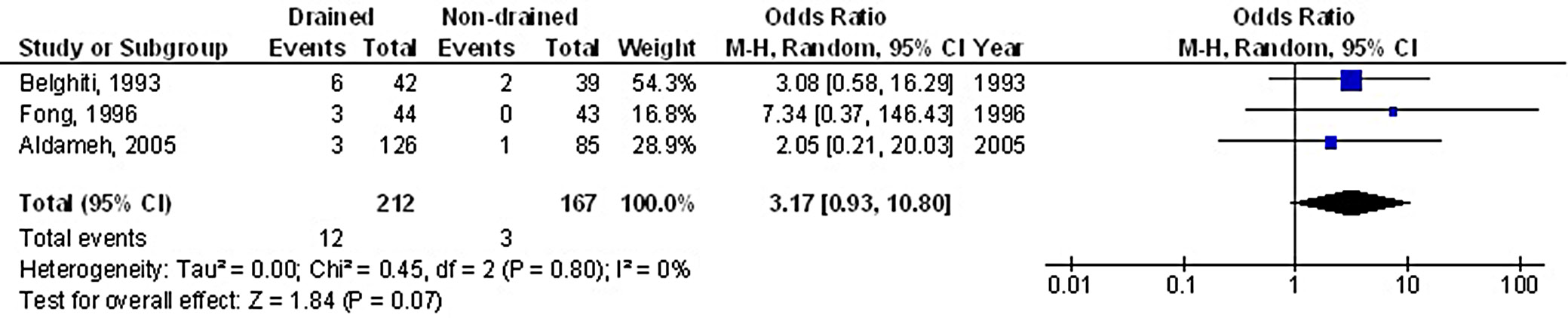

Prophylactic drainage was associated with a significantly higher risk of superficial surgical SSWI, with OR of 1.97 (95% CI: 1.09–3.55, p = 0.02), and substantial heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 79%), as shown in Figure 2. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the PD and non-drainage groups in terms of IIACs, with an OR of 3.17 (95% CI: 0.93–10.80, p = 0.07) and no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), as illustrated in Figure 3.

The use of stratified models to assess the effects of specific factors – such as age, gender and ethnicity – on comparative outcomes was not feasible due to insufficient data. The quantitative Egger’s regression test and visual inspection of the funnel plots (Figure 4, Figure 5) indicated no evidence of publication bias (p = 0.86 and 0.92, respectively). Nonetheless, selective reporting bias was ruled out, although most of the included RCTs exhibited inadequate procedural quality.

Discussion

In the studies included in this meta-analysis, a total of 5,459 LRs were initially reported. Of these, 2,918 procedures involved the use of PD, while 2,541 were performed without drainage.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32

Each author employed a closed suction drain inserted through a separate stab incision.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The use of surgical drains is well-established and based on various assumptions, including the need to monitor potential postoperative complications and to mitigate their effects.33 Surgeons advocating for routine PD after LR argue that drains can divert ascitic fluid away from the incision, reduce bile leakage, prevent intra-abdominal fluid collections, and enable early detection and quantification of hemorrhage. Nevertheless, a number of authors have expressed concern that drains might raise morbidity.29, 34 Since some of the research was led prior to the release of the extensively utilized Clavien–Dindo classification, we discovered that the concept of serious problems varies depending on the research.35 Routine ultrasound evaluation of all patients may have contributed to overdiagnosis by detecting clinically insignificant findings that would not have otherwise manifested symptoms or required intervention.36 Only 1 study concluded that ultrasound should be reserved for symptomatic patients, suggesting that routine imaging in asymptomatic individuals may lead to unnecessary interventions or overdiagnosis.36 The findings of this research demonstrated that routine use of drainage did not improve major or secondary outcome measures, and, in fact, was associated with a significantly increased incidence of ascitic leakage. The likelihood of surgical SSWIs varies considerably depending on the type of LR performed, ranging from 9.7% in segmentectomies to 18.3% in trisectionectomies.37 This highlights the importance of maintaining comparable rates of extended LRs across studies. Additionally, the criteria for drain removal varied between studies, further contributing to heterogeneity in outcomes. According to recent research employing the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) standardized definition and grading of bile leakage, drains should be removed on the 3rd postoperative day if the bilirubin concentration in the drain fluid is less than 3 mg/dL.38 The literature reports that the incidence of bile leakage following LRs ranges from 3.6% to 12%.39 Additionally, another study found no significant difference in bile leakage rates between laparoscopic and open procedures, with reported rates ranging from 4% to 17%.40 Given that these conditions could have potentially biased the outcomes in favor of patients who received drains, the absence of a statistically significant difference strongly supports a no-drain strategy.

Limitations

Due to the exclusion of several studies, variability bias may have emerged. However, the eliminated studies failed to satisfy the requisite criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Furthermore, we lacked sufficient information to ascertain whether variables such as gender, race and age impacted the outcomes. The objective of the study was to determine the influence of PD and non-PD on SSWI for LRs management. Bias in this study may have been exacerbated by the inclusion of incomplete or erroneous data from previous research. Additionally, individual factors such as age, gender, race, and nutritional status likely contributed to variability and potential confounding. The absence of data on these variables limits subgroup analysis and may distort the results. Furthermore, the exclusion of unpublished studies and grey literature introduces a risk of publication bias, potentially skewing the overall findings.

Conclusions

Further research is essential. This need has also been emphasized in previous studies that showed comparable effect estimates using similar meta-analytic approaches. Future investigations should aim to address current data limitations, reduce heterogeneity and incorporate standardized methodologies to improve the reliability and generalizability of the findings.41, 42, 43, 44 People who underwent LRs with PD had a significantly higher rate of SSWIs compared to those without PD. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the PD and non-PD groups in terms of IIACs. It is important to interpret these results cautiously, as the meta-analysis included a limited number of studies for some comparisons. In particular, the low p-value observed for IIACs may affect the reliability and statistical significance of the findings.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.

.jpg)

.jpg)