Abstract

Background. Porphyromonas gingivalis is a major human oral opportunistic pathogen and a key etiological agent of periodontal disease, contributing to inflammation and bone loss in the oral cavity. Periodontitis is not limited to oral health complications; it has also been associated with a range of systemic conditions, including coronary heart disease (CAD), respiratory disease, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and certain types of cancer.

Objectives. Immunization-based prevention of periodontitis appears to be a promising strategy; however, no vaccine is currently available for commercial use. In the present study, a novel vaccine candidate against P. gingivalis was proposed, consisting of a P. gingivalis protein, gingipain, glycosylated with the carbohydrate moiety of P. gingivalis lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Materials and methods. Glycosylation of gingipain was achieved in Escherichia coli by introducing the Campylobacter jejuni N-glycosylation system, the P. gingivalis LPS biosynthetic pathway and the gingipain gene.

Results. The neoglycoprotein was purified using column chromatography to a purity exceeding 99%, yielding a soluble antigen. The modified protein was recognized by commercial antibodies targeting the protein backbone, the carbohydrate moiety, and a custom monoclonal antibody specific to the purified LPS of P. gingivalis American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 33277. The glycoprotein was used to immunize mice, and the resulting sera were analyzed for their ability to opsonize bacterial cells. The absence of detectable opsonization suggests that the elicited antibodies are more likely directed against the protein component of the vaccine rather than the glycan surface antigen.

Conclusions. The final product was most likely assembled correctly, as it was recognized by LPS-specific antibodies. Further evaluation in an animal model of induced periodontitis is necessary to determine whether the elicited antibodies can effectively inhibit gingipain released by the pathogen. If this vaccine candidate demonstrates protective efficacy, the approach could accelerate and enhance the safety of vaccine design against a wide range of other pathogens.

Key words: vaccine, glycoconjugates, Porphyromonas gingivalis, gingipain, periodontosis

Background

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a common human opportunistic pathogen of the oral cavity. The bacterium is a facultative anaerobe responsible for the destruction of dental tissue, leading to periodontosis.1 It is highly difficult to culture in vitro, which hampers studies on its physiology and virulence. However, with the recent advances in genome sequencing and systems biology, it has been possible to elucidate a large part of its metabolic pathways.2 The recently published corrected DNA sequence3 of the original data4 on P. gingivalis and the other published sequences enabled a comparison with the metabolic pathways of other systems, specifically the well-known Escherichia coli genome and metabolome.5, 6 The analysis identified multiple therapeutic targets and potential prophylactic strategies.7 The last aspect of the analysis is important as it is more cost-efficient to prevent the disease than to treat it.

There is no commercially available vaccine against periodontitis or P. gingivalis. Existing strategies rely on a combination of gingipains with other components, most likely fimbriae8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 or hemagglutinin adhesion.8 A capsular polysaccharide was also tested and was found superior to the pure protein antigens.14

Analysis of DNA genomes of P. gingivalis showed that the pathogen produces at least 2 proteases, the Arg-type gingipain and the Lys-type gingipain.15 The proteins are highly homologous and used by the bacterium to cleave host proteins, including bone tissue of teeth,16 leading to the destruction of periodontal tissue.17 The gingipain protein sequences also contain adhesin motifs, potentially responsible for the recognition and attachment to the host’s cell surfaces.18 Research performed by other groups identified a type IX secretion system (T9SS) responsible for gingipains’ secretion.19, 20 The blockade of this system was proposed as an indirect strategy for the prevention of periodontitis caused by P. gingivalis.21

Objectives

Systems biology analysis of the metabolic network has identified conserved pathways involved in the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) synthesis in P. gingivalis.2 The LPS is a major constituent of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Glycoconjugates composed of the carbohydrate portion of LPS coupled to carrier protein have been employed as vaccine candidates in numerous studies, while glycoconjugates of capsular polysaccharides of Hemophilus influenzae type B, Neisseria meningitis and Streptococcus pneumoniae are already successfully implemented into vaccination regime. Considering studies on the role of LPS in P. gingivalis infection and seroprotection,15, 16, 17 we commonly reasoned that LPS is a good antigenic target for a vaccine against P. gingivalis. We also proposed using gingipain as a dual-function component, serving both as a carrier for the LPS carbohydrate moiety and as a proteinaceous antigen.10, 22, 23, 24 However, the metabolic pathways involved in LPS biosynthesis have not been fully elucidated through experimental studies. The pathogen produces 2 distinct types of LPS, one carrying the O-polysaccharide and the A-LPS containing anionic polysaccharide (APS), with different repeating unit structures.25, 26 The synthesis pathways of the outer carbohydrate O- and A-antigens are poorly understood. Therefore, a comparison with other systems is used to assign putative roles to genes and assemble operons responsible for the synthesis of similar structures in other pathogens.27, 28, 29

Glycans are generally poor antigens, and require conjugation with proteins, most notably the inactivated toxoids from different bacterial species, in order to render T-dependent antigenic character and elicit an effective immune response.30 Currently, 5 carrier proteins are licensed as components of glycoconjugate vaccines: a genetically modified cross-reacting material (CRM) of diphtheria toxin, tetanus toxoid (T), meningococcal outer membrane protein complex (OMPC), diphtheria toxoid (D), and H. influenzae protein D (HiD).31

In the USA, the only adjuvant approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary vaccination is aluminum hydroxide, which significantly limits the effectiveness of carbohydrate-based vaccine components.32 Other adjuvants, based on the synthetic LPS component monolauryl phosphate (MLP) or synthetic cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) nucleotides, have been underrepresented in licensed vaccines.32 Adjuvants based on squalene oil, a natural product derived from marine mammals, are not recommended due to their animal source, despite being used in commercial vaccines against influenza.33

Standard methods for the formation of glycoconjugates are based on the chemical coupling of carbohydrates with a protein via various chemical strategies. This approach raises many issues that have to be addressed in the production process, like reproducibility, yield, purification from undesired chemical modifications, and others. There is an area for improvement, but addressing these challenges may require innovative strategies beyond traditional approaches.

An alternative strategy to couple carbohydrate antigens to peptide or protein is based on the utilization of Campylobacter jejuni undecaprenyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein-glycotransferase (PglB) glycosyltransferase.34 The enzyme catalyzes carbohydrate transfer to the side-chain amide of Asparagine (Asn) in the recipient peptide with a defined acceptor sequence D/E-X-N-X-S/T. The transfer process is relatively inefficient, and numerous studies have been conducted to improve its efficiency. Finally, a double mutant (RR → DL) in the original PglB sequence was identified, exhibiting broad transfer specificity for the Asp-Tyr-Asn-Ala-Thr (DYNAT) acceptor sequence.35, 36 The final step involved removing the competing O-antigen ligase (WaaL in E. coli) to eliminate the native pathway responsible for transferring the host-synthesized O-antigen to the lipid core. This strategy has been successfully demonstrated using the Burkholderia mallei O-antigen to create a recombinant vaccine covalently linked to a protein.37 Additionally, N-glycan transfer-based technology has been applied in the development of other vaccines.38, 39, 40

In the current work, a novel strategy has been used to design a genetic system to produce a vaccine candidate against P. gingivalis. The genes synthesizing O-antigen in P. gingivalis have been identified computationally using various software, transferred into E. coli and co-expressed with a mutated C. jejuni pglB gene and the P. gingivalis antigens, termed pI, fused with the recognition sequence for the PglB transferase. The construct produced a modified antigen which was recognized by antibodies raised to all fragments of the derivatized protein.

Materials and methods

Microbial strains

Campylobacter jejuni strain RM122141 was obtained from Prof. Anna Pawlik at the Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Wrocław, Poland. Porphyromonas gingivalis strain DSM 20709 (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 33277) was obtained from the Leibniz Institute DSMZ (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany). Escherichia coli cloning strains were purchased from 2 suppliers (Lab–Jot sp. z o.o., Warsaw, Poland; Life Technologies sp. z o.o., Warsaw, Poland). Saccharomyces cerevisiae cloning strain MaV203 was supplied with the GeneArt High-Order Genetic Assembly Kit (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.). The E. coli protein expression strains BL21(DE3) and its variants were purchased from Merck (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o., Poznań, Poland) or from New England Biolabs (Lab-Jot sp. z o.o.).

Microbial growth media

Bacterial media were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.) or BTL (BTL Sp. z o.o., Łódź, Poland). Antibiotics for bacterial selection were obtained from Merck (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.). Auxotrophic yeast selection medium Complete Supplement Mixture (CSM) was supplied with the GeneArt High-Order Genetic Assembly Kit (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.). Yeast cells were grown on CSM medium supplied with glucose, included in the GeneArt High-Order Genetic Assembly Kit, at 30°C for 3 days.

Culture od P. gingivalis for LPS isolation

Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277 strain was revitalized after lyophilization under anaerobic conditions (BD GasPak EZ Anaerobe Container System, ref. 260678; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA) on Columbia Agar (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.) plates supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood. The bacterial growth was carried out at 37°C for 5–7 days. Bacterial mass was collected, suspended in Columbia Broth (BioWorld, Dublin, Ireland), centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 30 min (HERMLE Labortechnik Z36HK, Wehingen, Germany) and the bacterial pellet was freeze-dried (Lablyo Freezedrier, York, UK).

Bacteria were typically selected on Miller–Hinton agar plates with appropriate antibiotics: ampicillin (50 µg/L), kanamycin (50 µg/mL), spectinomycin (50 µg/mL), or chloramphenicol (25 µg/L). Bacteria were grown on an appropriate selection plate or in a Luria–Bertani liquid medium supplied with appropriate antibiotics at 37°C for 12–24 h. Longer growth times for bacteria were needed for constructs in the final phases of assembly.

Chemical reagents

Common chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.). Chromatography columns were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.) or VWR (VWR sp. z o.o., Gdańsk, Poland). Imidazole (p.a.) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.). TCEP-HCl was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.).

Primary and secondary antibodies

Mouse α-6 × Histidine (His) monoclonal antibody and biotin-conjugated goat α-mouse IgM secondary antibody were purchased from Life Technologies (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.). Mouse α-P. gingivalis strain W83 monoclonal antibody was obtained from Creative Diagnostics (CD Biosciences, Shirley, USA). Rabbit polyclonal α-P. gingivalis and α-gingipain R1 (a.a. 228–720) antibodies were purchased from antibodies on-line (antibodies on-line, Aachen, Germany). The streptavidin-HRP conjugate was bought from Sigma Aldrich (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.).

Monoclonal antibodies against P. gingivalis LPS were raised using P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 strain bacterial mass as an immunogen and a purified LPS as an antigen for screening in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) . The LPS was prepared from a dry mass (35 mg) of P. gingivalis via extraction with Trizol reagent according to the protocol described by Yi and Hackett.42 The generation of the hybridoma cell lines was performed using a standard procedure,43 with some minor modifications. Briefly: 7-week-old Balb/c mice were immunized 4 times at 2-week intervals with 50 µg of dry bacterial mass suspended in 100 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and emulsified with an equal volume of Freund’s incomplete adjuvant; 2 × 50 µL was given into a skin fold in the lumbar region and the remaining portion intraperitoneally. The final boost (4th injection) was administered intraperitoneally without adjuvant. Two days later, the animals were euthanized and spleens harvested for cell isolation. Splenocytes were fused with Sp2/0-Ag14 myeloma cells according to the standard method with polyethylene glycol (PEG). Hybridoma colonies were screened using ELISA on 96-well microtiter plates coated with P. gingivalis LPS. Positive wells were subjected to repeated cloning (3 times) using the limiting dilution method to ensure monoclonality. Hybridoma clones were expanded and adapted to grow in hybridoma serum-free medium (CD Hybridoma Medium, CD Biosciences; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) for antibody production. Antibody class was estimated using the Mouse typer isotyping kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA), indicating IgM class. Finally, a portion of the antibody was purified in an Maltose-binding protein (MBP) agarose column (Pierce, Rockford, USA), according to manufacturer protocol.

Animal experiments obtained approval from the Committee for Animal Experiments at Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Polish Academy of Sciences (approval No. 062/2023). Porphyromonas gingivalis and C. jejuni were grown on Q (a specialized culture medium used for the isolation and growth of P. gingivalis) agar plates under anaerobic conditions at 37°C. Typically, bacteria were grown for 3–4 days and the number of bacteria from 1 agar plate was enough for isolation of genomic DNA.

Cloning vectors

Yeast shuttle cloning vector pYES1 linearized (pYES1L) was supplied with the GeneArt High-Order Genetic Assembly Kit (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.). Bacterial subcloning vectors were obtained from the TOPO XL-2 Cloning Kit (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.) or the NEB PCR Cloning Kit (Lab-Jot sp. z o.o.). Destination vectors: pACYCDUET-1, pETDUET-1, pRSFDuet-1, and pCDFDuet-1 were purchased from Merck (Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.).

Site-directed mutagenesis

The procedure was performed with GeneArt Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.) on plasmids with size up to 13 kb or with Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Lab-Jot sp. z o.o.) on longer plasmids.

Bioinformatics analysis

Reconstructed metabolic networks of bacteria were obtained from the BioCyc database.5 Pathways involved in cell wall biosynthesis were selected for E. coli as a reference and compared with P. gingivalis pathways. Due to a later revision of the originally deposited genome assembly for P. gingivalis ATCC 33277, the hits were corrected manually. Genes identified as potential hits were analyzed with PathwayTools software available within the BioCyc database to identify operons and other genes potentially involved in LPS biosynthesis in P. gingivalis.

Since the database does not have identified pathways for LPS biosynthesis besides for E. coli, an additional search was performed within the Prokaryotic Operon Database ProOpDB44 to identify genes involved in LPS biosynthesis.

The final assignment was performed by comparing whole genomes with the Mauve tool45 using E. coli K-12 as a reference strain and P. gingivalis W83 strain, in which some genes involved in LPS biosynthesis have already been identified.28

Genomic DNA isolation

Whole genome nucleic acids were isolated from a single Q agar plate using a Genomic Mini kit from A&A Biotechnology (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland).

DNA cloning and assembly

Genes assigned as having roles in LPS biosynthesis were amplified with Platinum Superfine (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.) or Q5 Hot Start (Lab-Jot sp. z o.o.) DNA polymerases according to manufacturer’s instructions, separated on an agarose gel, excised, and extracted with Monarch DNA Gel Extraction kit (Lab-Jot sp. z o.o.). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified genes were used directly for subassembly of smaller parts or subcloned into appropriate vectors using the TOPO XL-2 Cloning Kit (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.) or the NEB PCR Cloning Kit (Lab-Jot sp. z o.o.).

pACYC/pET/pCDFDuet-1 vectors assembly

Assembly of fragments was performed with the GeneArt High-Order Genetic Assembly System (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The 1st assembly was performed in the yeast strain MaV203 with up to 6 inserts/vector and the fragment order was verified with a single colony PCR amplification using primers spanning putative fragment junctions. The product size was selected not to exceed 600–700 bp due to the known restrictions of the PCR approach. In the 2nd round, the fragments were reassembled into the yeast pYES1L vector to obtain a single fragment. The 3rd assembly stage used that fragment and the destination vector. As before, the verification was performed with a single colony PCR. The final construct was verified using Sanger DNA sequencing on fragments amplified by PCR.

The strategy with the yeast shuttle vector created problems at the 3rd assembly stage when moving the constructs into E. coli. Therefore, it was decided to use up to 3 fragments per assembly directly in E. coli employing the GeneArt Plus Seamless Assembly System (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.). Fragments were amplified directly from genomic DNA with the 2nd fragment typically preceded by an internal ribosome entry sites (IRES) sequence and assembled into the expression vectors according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene order was verified with PCR of junction sequences and the ends were verified by partial DNA sequencing. Due to the length of constructs and general difficulties with amplification of long DNA fragments, attempts to fully sequence the constructs were not successful. The final strategy was as follows: The gene fragment pI, corresponding to the modified antigen for the pRSFDuet-1 vector, was codon-optimized for E. coli and synthesized using GenScript. The pglB gene was cloned from C. jejuni genomic DNA using NEB PCR cloning kit (New England Biolabs), mutated to contain RR>DL replacement35 and assembled into pRSFDuet-1 using GeneArt Genetic Assembly System (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The remaining genes for pACYCDuet-1, pCDFDuet-1 and pETDuet-1 vectors were cloned from the genomic DNA of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 strain (gingipain fragments, LPS biosynthetic pathway genes) using standard molecular biology techniques.

Protein expression and purification

Plasmids pACYCDuet-1, pETDuet-1, pRSFDuet-1, and pCDFDuet-1 with cloned inserts were transformed into BL21(DE3) chemically competent cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Clones were selected on Luria–Bertani or Miller–Hinton agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (25 µg/mL), ampicillin (50 µg/mL), kanamycin (50 g/µmL), and spectinomycin (50 µg/mL).

To express proteins, a single colony from the selection plate was added to 3 mL of lysogeny broth (LB) medium supplemented with antibiotics and grown at 37°C with constant shaking (150 rpm; Excella 24R; Excella, Hamburg, Germany) overnight. The next day, 300 µL of the culture was added to a fresh 30 mL LB medium supplemented with antibiotics and grown at 37°C with constant shaking for about 2–3 h to become visibly turbid (optical density (OD) 600 = 0.4–0.6). The culture was added to 3 L of Terrific Broth (TB; Thermo Fisher Scientific) medium in baffled flasks supplemented with antibiotics and grown as before to reach OD600 = 0.4–0.6. At this point, the culture was cooled down at room temperature for about 30 min and isopropyl β-D-1-tiogalatopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.2 mM. The culture was incubated again at 18°C with vigorous shaking (300 rpm; Excella 24R) for 16–20 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g, 4°C for 30 min (Sorvall Lynx 6000 centrifuge, and Fiberlite F12- 6x500 LEX rotor; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The combined cell paste was stored at −80°C for processing.

The frozen cells from a 3L bacterial culture were thawed by warming at room temperature for about 30 min and resuspended in 200 mL of ice-cold extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 20 mM imidazole, pH = 8.0, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)-HCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)) supplemented with Complete EDTA-Free (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) protease inhibitor cocktail according to manufacturer’s recommendations. The cells were disrupted by sonication on ice (3 cycles of a 30 s burst followed by a 30-s cooling period; Ultrasonic Disintegrator model UD-11, power level 4; Techpan sp. z o.o., Puławy, Poland) and centrifuged at 50,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h using a Sorvall LYNX 6000 (A27-8x50 rotor; Thermo Fischer Scientific) centrifuge.

The supernatant was collected, and MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 5 mM to complex with EDTA. The mixture was loaded directly onto a preequilibrated Ni-agarose column (5 × 5 mL HisTrap crude + 1 × HisPrep FF 16/10) connected to an AKTA START (GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA) system at 1–2 mL/min flow rate of the loading buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 20 mM imidazole, pH = 8.0, 1 mM TCEP-HCl), and the column was washed with 5 column volumes (CV) of the loading buffer and developed with a stepwise elution by imidazole: 5 CV of loading buffer with 20, 250 and 500 mM imidazole, pH = 8.0. Fractions were analyzed with sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), subjected to rapid buffer exchange on desalting columns (2 × HiPrep 26/20 Desalting) against buffer A (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 8.0, 10% v/v glycerol, 1 mM TCEP-HCl) and loaded onto Q Sepharose anion exchanger (5 × 5 mL HiTrap Q Sepharose HP) at 2 mL/min flow rate. The column was washed with 5 CV of buffer A and developed with a 0–100% gradient of buffer B (buffer A+ 1M NaCl) over 20 CV at 2 mL/min flow rate. Column fractions were examined with SDS-PAGE, and positive fractions, as judged by molecular weight and western blotting results with anti-gingipain and anti-His antibodies, were diluted with an equal volume of hydrophobic interactions chromatography (HIC) buffer A (2 M ammonium sulfate, 10% glycerol v/v, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 8.0, 1 mM TCEP-HCl) and loaded onto HiScreen Phenyl HP column (1 × 4.7 mL; GE Healthcare) at 1 mL/min flow rate. The column was washed with 3 CV of HIC buffer A and developed with a 0–100% gradient of HIC buffer B (HIC buffer A without ammonium sulfate) at 1 mL/min flow rate. Fractions were examined using SDS-PAGE for molecular weight and reactivity with anti-His and anti-gingipain antibodies. Positive fractions were pooled and stored at −20°C for further examinations.

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

The protein electrophoresis was routinely performed on 10% acrylamide gels using the FastCast premixed solutions (Bio-Rad) or MiniProtean TGX precast 4−20% 10-well minigels (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. All gels were run under reducing conditions and protein detection was performed with NOVEX Colloidal Blue Staining Kit (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.). To detect proteins by specific antibodies, the gels were transferred to a 0.22-µm Whatman Westran S polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.) or a 0.45-µm Pierce nitrocellulose (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.) membrane using a MiniProtean Western Blotting wet transfer module (Bio-Rad) either overnight or for 1 h, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Western blotting

Following wet transfer, samples were incubated with primary antibodies in blocking buffer (3% non-fat dry milk, 0.05% Tween-20 in 1× Tris-buffered saline, pH 8.0) for at least 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. The antibodies were used at the following dilutions: α-His – 1:2,000; α-gingipain – 1:5,000; α-LPS IgG – 1:5,000; and α-LPS IgM – 1:2,000.

After washing 5 times with 10 mL 1 × TBST for 5 min, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies coupled to biotin diluted 1:10,000 for 2 h at room temperature, washed again with 1 × Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST) as before and incubated with a 1:500,000 diluted streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate for 2–3 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed 7 times with 10 mL of 1 × TBST and additionally 2 times with 1 × TBS. Drained membranes were overlaid with TMB Enhanced One Component HRP Membrane Substrate (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck Life Sciences sp. z o.o.) or Pierce 1-Step ULTRA Blotting Solution (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Developed membranes were visualized using an in-house imaging system based on Nikon D7100 camera equipped with an AF-S Micro Nikkor 60 mm 1:2.8 G ED lens (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Images were transferred to a laptop with NikonTransfer2 software, converted to a *tiff format with Adobe CS2 software (Adobe Inc., San Jose, USA) and saved for further manipulation. Due to the overall blue background of the TMB substrate, the images were minimally enhanced to remove the background.

Results

General strategy

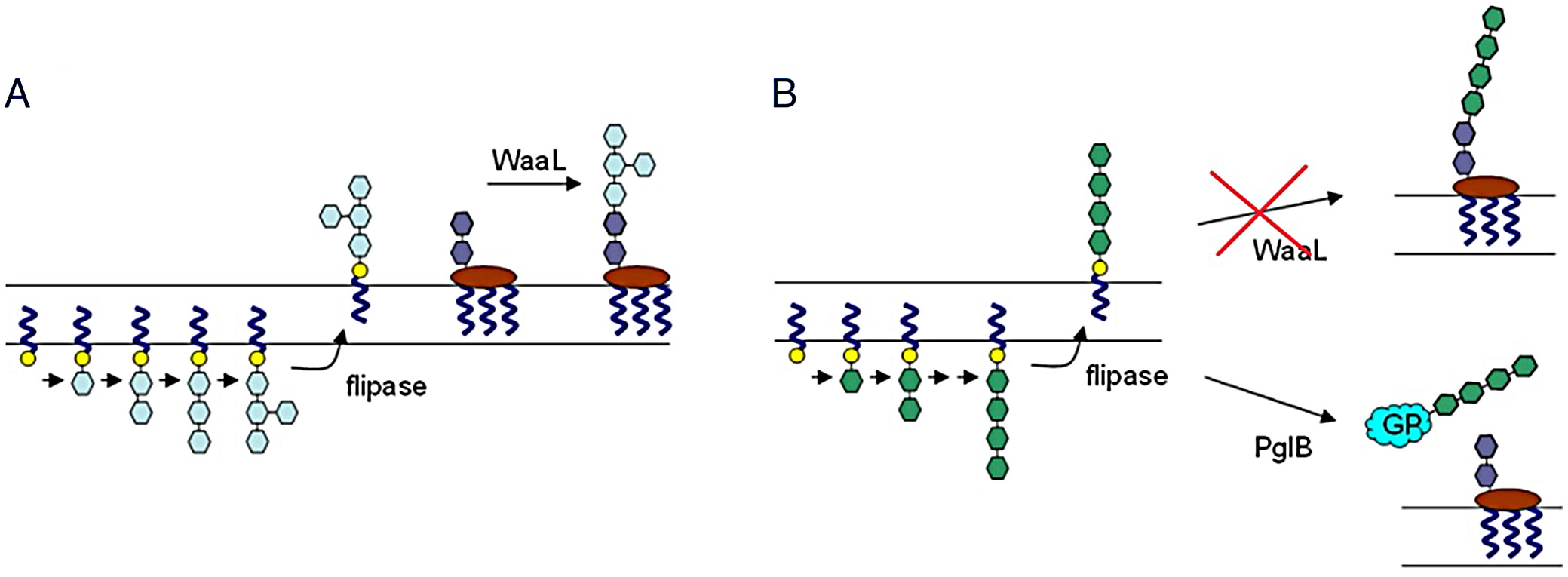

The overall concept for the formation of neoglycoconjugate composed of P. gingivalis gingipain and O-antigen is presented in Figure 1. The original biosynthetic pathway responsible for the synthesis of O-specific antigen (Figure 1A) was identified via systems biology analysis and then transferred into E. coli. The host’s waaL ligase gene was removed and replaced with an engineered pglB glycosyltransferase gene from C. jejuni (Figure 1B).

Genome analysis and pathways identification

Analysis of the genome of P. gingivalis strain ATTCC 33277 was performed with BioCyc software PathwayTools.5 The search identified conserved genes based on the putative function assignment according to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database of metabolic pathways.46 However, the analysis was limited in scope as the similarity of genes between the BioCyc reference, E. coli K-12 strain and the P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 genome was too low to have an unambiguous assignment. Therefore, the P. gingivalis genome was analyzed again using the prokaryotic operon database ProOpDB44 to identify putative operons involved in LPS biosynthesis (KEGG pathway 0540). The performance was verified on known E. coli genomes and the cataloged pathways available in EcoCyc6 and KEGG databases.46 The result of the analysis of the P. gingivalis genome was again compared with the genome of E. coli K-12 strain to identify genes with a function similar to the E. coli genes involved in LPS synthesis (EcoCyc database). The results were compared by whole genome alignment of E. coli and P. gingivalis W83, W50 and ATCC 33277 genomes to find potential rearrangements. The final results identified 36 genes belonging to 8 metabolic pathways (Table 1). Only 1 gene was identified directly as involved in O-antigen biosynthesis (pgn0223) and 2 in capsular antigen biosynthesis (pgn1524->pgn1525). The Lipid IVA biosynthesis genes (pgn0206, pgn0544), as well as the dTDP-L-rhamnose biosynthetic pathway I genes (pgn0546->pgn0549) were also identified. The former is a part of a broader lipid IVA biosynthesis pathway, while the latter is the common enterobacterial antigen biosynthesis pathway identified using the PathwayTools software in the BioCyc database.

The pgn1243 gene product (Table 1) is involved in O-antigen biosynthesis in many Gram-negative bacteria. The gene is part of a larger operon pgn1245->pgn1240 (BioCyc database, PathwayTools prediction). In E. coli, the ortholog of pgn1243 is involved in the production of colanic acid,47 a part of the E. coli capsular antigen. Transposon mutagenesis of P. gingivalis showed that the gene is essential for LPS biosynthesis.48

Gene pgn1251 has a dual function in type A and type O LPS biosynthesis in P. gingivalis.49 It is also essential for pathogen growth.50, 51 Genes pgn0361, pgn1239->pgn1240 and pgn1668 have been shown to be involved in type A LPS biosynthesis.52 Due to technical problems with assembling different operons in E. coli (described later), the genes pgn0361 and pgn1668 are not listed in Table 1 despite having been identified in the ProOpDB search.

Genes pgn0223->pgn0244 form an operon (BioCyc, PathwayTools). The pgn0223 ortholog is involved in lipid and common enterobacterial antigen biosynthesis in E. coli.53 Genes pgn0224->pgn0229 are part of an operon (BioCyc database, PathwayTools software) whose members (WecC, RfaB) have orthologs in E. coli genome and are involved in bacterial lipid biosynthesis (KEGG pathways database).

Gene pgn0234 (Table 1) codes an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of the common enterobacterial in E. coli.54, 55 The E. coli operon has orthologs corresponding to only 2 genes, pgn0233 and pgn0234, from the P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 strain genome (BioCyc database, PathwayTools software).

Gene pgn0206 is part of a lipid IVA biosynthesis pathway (PGN_RS00965). The pathway is highly conserved in bacteria and could easily be identified in P. gingivalis due to the protein sequence similarity (BioCyc database, PathwayTools software).

Antigen identification and engineering

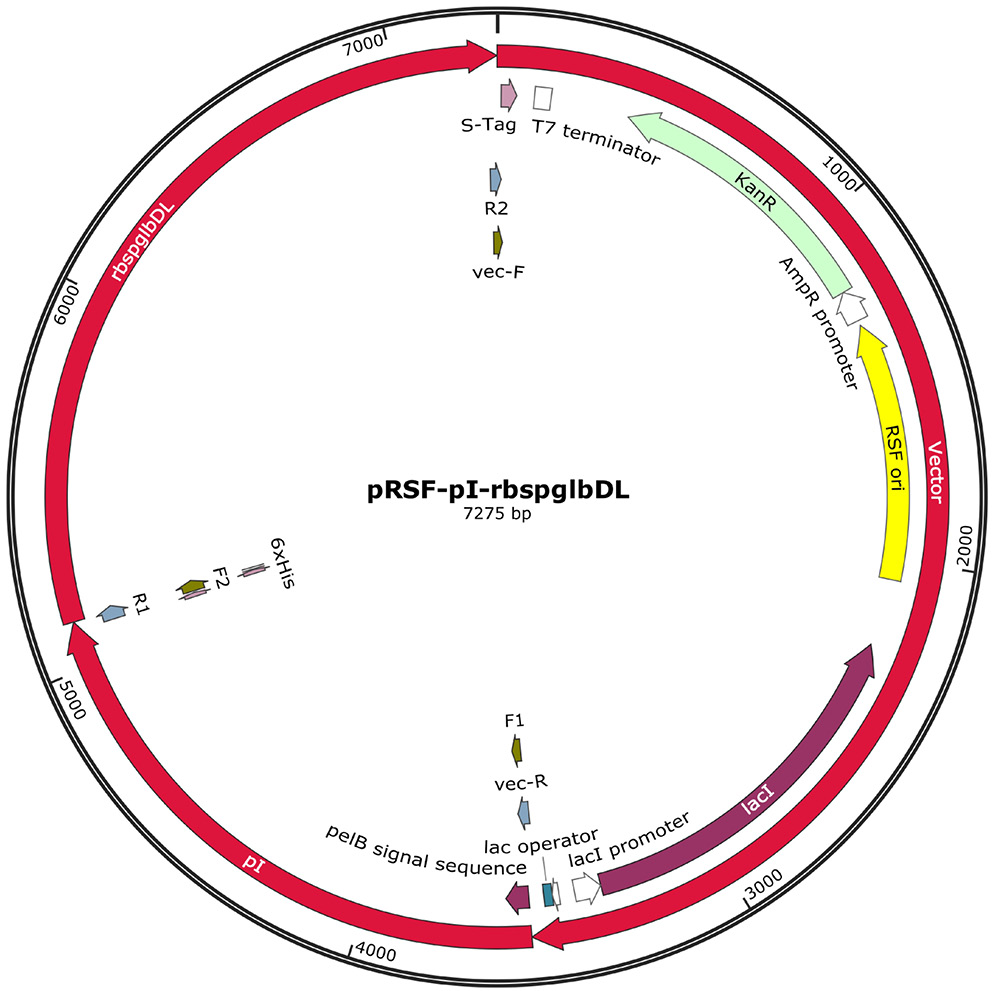

The choice of antigen for the vaccine construct was based on the literature data. Porphyromonas gingivalis secretes gingipains, Kgp and Rgp, which have been shown to be responsible for bone destruction and a general host protein proteolysis.17 Gingipains also contain cell adhesion domains that interact with proteins in the gum matrix, facilitating bacterial colonization.56 Since the whole gingipain is too large a protein for seamless recombination, fragments corresponding to the catalytic domain of Rgp gingipain have been used in fusion with the cell adhesion fragments (Figure 2).

The O-specific antigen is a substrate for the WaaL ligase that transfers the newly synthesized polysaccharide onto lipid A core oligosaccharide, a key step in LPS synthesis (Figure 1). Short forms of LPS (composed of Lipid A and core oligosaccharide) are present in rough serotypes of Gram-negative bacteria. Therefore, WaaL activity is not requisite for survival. To prevent O-antigen attachment to the LPS, the waaL gene was removed. The resulting strain of modified E. coli BL21(DE3) exhibited poor growth and was not stable in the presence of ampicillin, despite having an engineered β-lactamase gene as a resistance marker. Since the final construct was supposed to have multiple vectors, each with a separate resistance marker and a replication origin, it was decided to abandon the strategy assuming removal of the waaL gene from E. coli. Instead, the protein acceptor was modified with a removable 6xHis affinity tag to facilitate product purification on His tag affinity column.

Attachment of O-antigen was engineered to proceed to a triplicate DYNAT sequence previously used for glycosylation in bacteria. The strategy used here employed a modified C. jejuni pglB gene having a DL (aspartic acid, leucine) mutation introduced to relax the transfer specificity and increase the efficiency of produced glycoconjugates.35, 36 Finally, the engineered E. coli BL21(DE3) strain has 2 parallel active pathways for the attachment of O-antigen in the original E. coli pathway and the modified pathway from P. gingivalis exerted by the mutated PglB protein. Since the PglB is a membrane protein, the original antigen containing gingipain sequence fragments was modified to include a periplasmic secretion signal pelB attached to the N-terminus (Figure 2).

Genetic assembly and pathway reconstruction

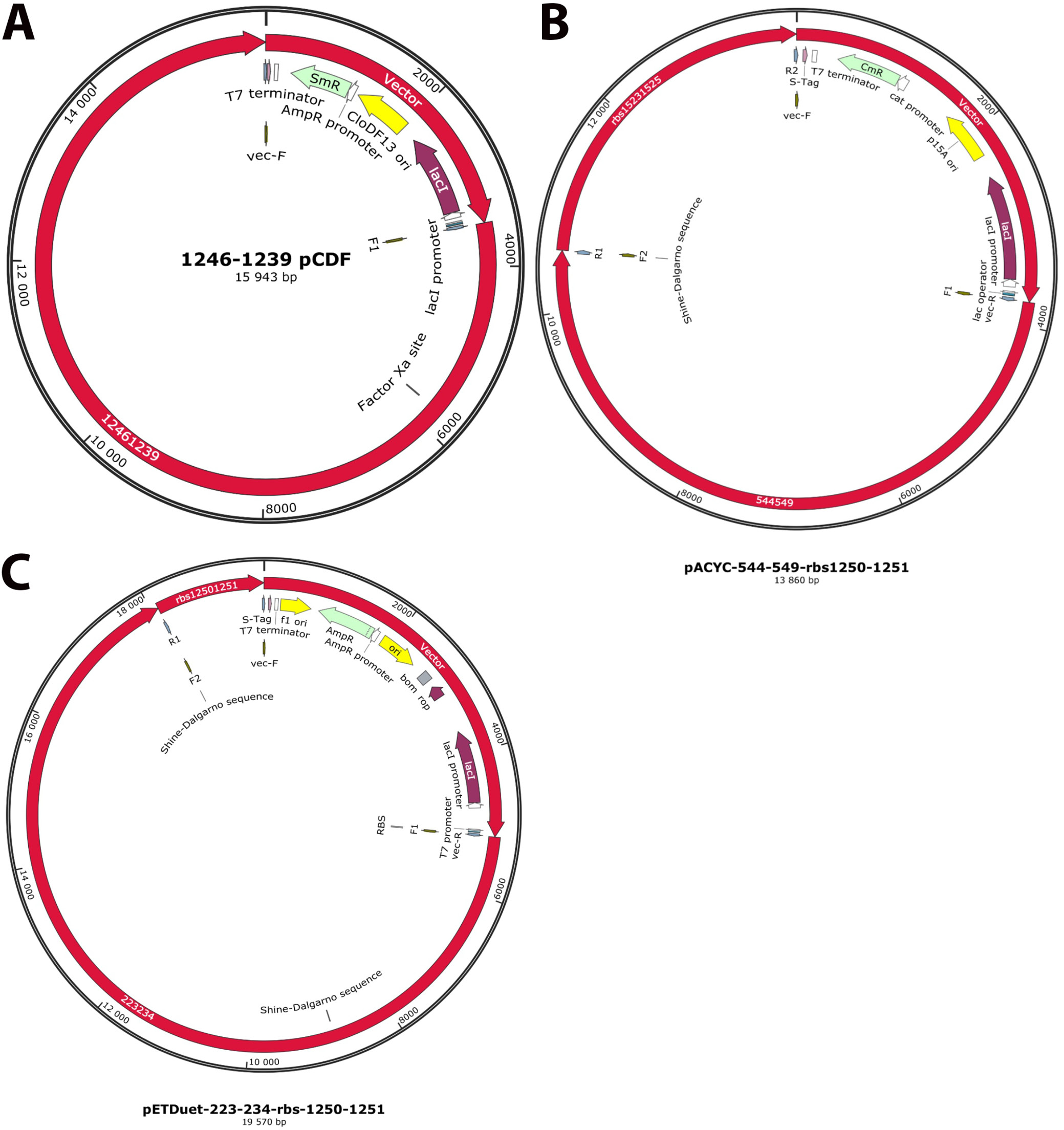

The number of genes and the length of the potential construct were not optimal for a single vector. It was decided that the genes would be split into 4 separate vectors: pRSFDuet-1, pETDuet-1, pCDFDuet-1, and pACYCDuet-1. The vectors allow stable co-expression of up to 8 gene fragments under the control of separate T7 promoters57 and the strategy has been used in the past by different groups.58, 59

The sequences were arranged to conserve transcription order with linkers followed by ribosomal binding sites attached to new reading frames. The final gene arrangements in the pCDFDuet, pETDuet and pACYCDuet vectors, each containing genes involved in P. gingivalis LPS biosynthesis, are presented in Figure 3.

Protein expression, purification and analysis

Assembled plasmids were used for protein expression in E. coli BL21(DE3) strain. The presence of all 4 plasmids significantly reduced bacterial growth. Initial attempts to grow the cells at 37°C during the induction phase were not successful due to protein degradation. Also, the main protein band detected in total cell lysate corresponded to a lower molecular weight species when examined using anti-His antibodies. Therefore, the cells were grown in TB medium at 37°C without induction and cooled down to room temperature before adding IPTG. The growth temperature was also lowered to 18°C to allow for protein induction while preventing protein degradation. The strategy resulted in a soluble protein after the first Ni-agarose purification.

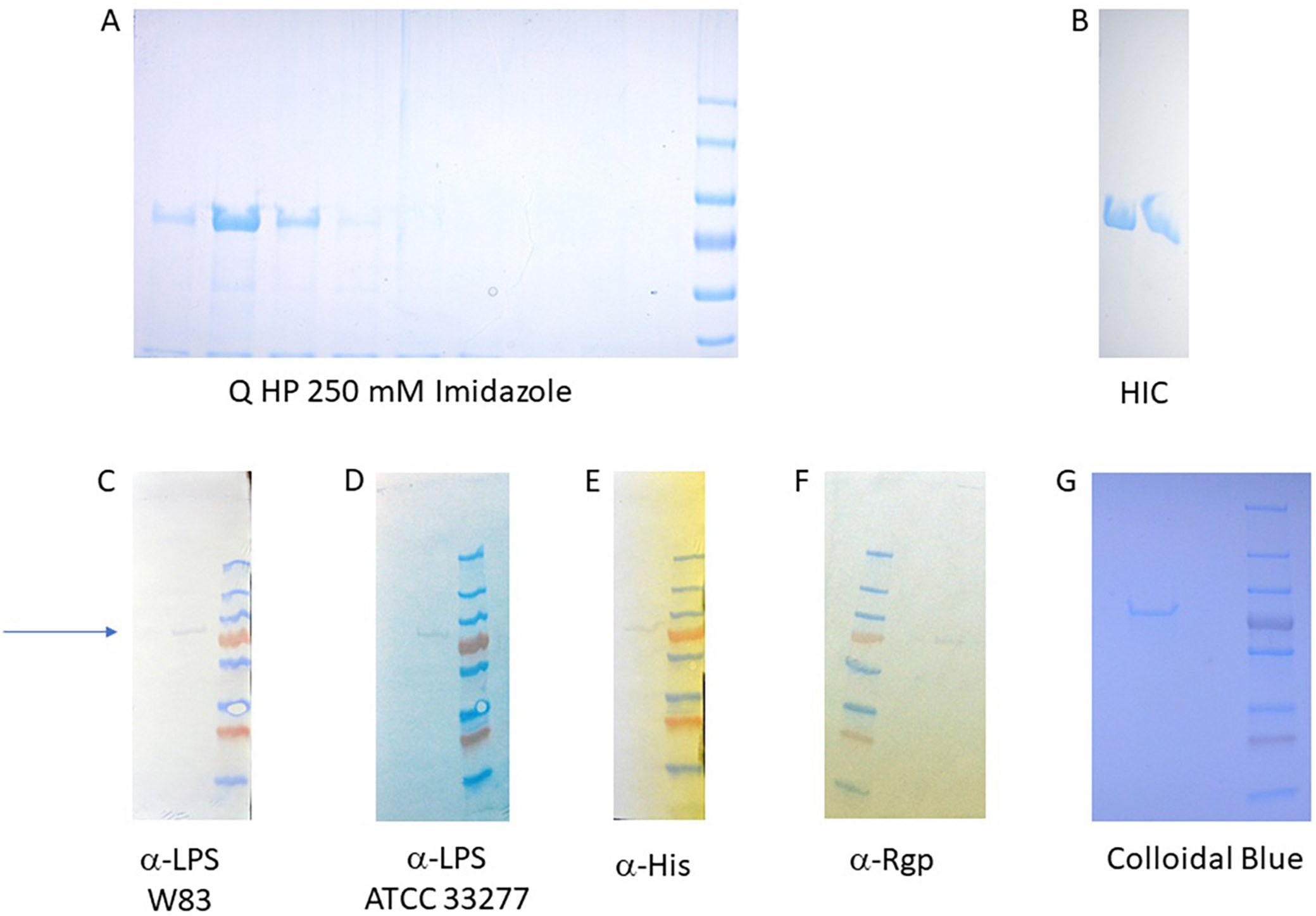

However, the main anti-His band corresponded to a lower molecular weight, most likely the non-glycosylated product. Due to the low sensitivity of anti-LPS antibodies, the potentially derivatized antigen band at around 70 kDa was not visible on the same blot. The main protein fraction eluting at 250 mM imidazole was subsequently dialyzed and further purified using an anion exchange column. At this stage, the protein could be detected in the fractions eluting at around 150 mM NaCl concentration (Figure 4A).

The pooled fractions were subsequently applied to a high-resolution hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) column – HiScreen Phenyl Sepharose. The protein eluted near the end of the salt gradient (Figure 4B), indicating a high degree of hydrophobicity. This observation was supported by computational modeling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which suggested that the protein likely forms a stable dimer.

Final protein purity was assessed with SDS-PAGE using the Colloidal Blue Staining Kit (Life Technologies sp. z o.o.). The purified protein exceeded 99% purity (Figure 4A, G) and displayed an apparent molecular weight of approx. 70 kDa (Figure 4G). It was also successfully derivatized with the O-antigen from P. gingivalis strains W83 (Figure 4C) and ATCC 33277 (Figure 4D), and incorporated the fused pI antigen (Figure 4F).

Discussion

Periodontal diseases are an increasingly prevalent health concern influenced by multiple factors. Chief among these are poor oral hygiene and high consumption of refined sugars, especially in children, which together foster the proliferation of pathogenic oral microbiota, ultimately contributing to alveolar bone resorption and dental caries.60, 61 At least 3 major bacterial pathogens are implicated in human periodontal disease, with P. gingivalis emerging as one of the most prominent.62 Currently, no commercial vaccine is available, and ongoing research is focused on developing effective vaccination strategies.22, 63, 64 Several protein antigens have been proposed as vaccine targets. Notably, studies on vaccines against other Gram-negative bacteria have demonstrated that bacterial polysaccharides, particularly when conjugated to a protein carrier, can serve as highly effective immunogens. The O-antigen portion of LPS is particularly preferred, as it is highly strain-specific. Targeting the O-antigen helps minimize the risk of generating antibodies that cross-react with commensal bacterial flora.

Vaccine design strategies based on systems biology approaches to reconstruct putative bacterial pathways remain in the early stages of development. In particular, efforts to map carbohydrate biosynthetic pathways are often constrained by the limited experimental validation of in silico predictions, leading to significant gaps in available data.

In silico metabolic reconstruction of P. gingivalis polysaccharide biosynthetic pathways began shortly after the organism’s genome was sequenced.2 These analyses predicted the existence of 3 major extracellular carbohydrate components; however, to date, experimental evidence has confirmed only 2: type A and type O LPS.25, 26 The identification of additional components involved in LPS biosynthesis has largely been based on gene-level analysis, focusing on genes homologous to those in the well-characterized LPS biosynthetic pathways of enterobacteria (Table 1).

To facilitate the identification of vaccine candidates against P. gingivalis, the pathogen’s complete metabolome was reconstructed using in silico methods. Genes associated with the synthesis of the variable region of LPS were selected and introduced into E. coli (Table 1). Because many biosynthetic components are conserved between E. coli and P. gingivalis, gene selection was deliberately limited to reduce vector load and maintain plasmid stability (Figure 2, Figure 3). Antigen conjugation was also designed in E. coli by the inclusion of a mutated PglB enzyme to couple synthesized carbohydrate coats to the antigen (Figure 1). Unfortunately, removal of the competing waaL ligase gene from E. coli was not possible due to its detrimental effect on the survival of the host. Therefore, the mixture of the pI antigen derivatized with P. gingivalis and E. coli carbohydrates were separated chromatographically to a very high degree and the purified antigen was confirmed to contain the P. gingivalis O-antigen (Figure 4C,D). Due to a low amount of protein, attempts to determine carbohydrate structure were not undertaken.

While experimental verification of the full biosynthetic pathways proposed in this study was not conducted, selected components have been identified by other researchers (Table 1 and the Results section). The final product was most likely assembled correctly, as it was recognized by LPS-specific antibodies (Figure 4C,D). This strategy provides a proof-of-concept for designing future vaccine candidates without the need for toxoid conjugation or large-scale cultivation of pathogenic bacteria to isolate LPS. If the candidate demonstrates protective efficacy in an animal model of periodontitis, the approach could enable faster and safer vaccine development for a wide range of pathogens. Preparations for in vivo verification of the proposed periodontitis vaccine candidate are currently underway.

Conclusions

Although we faced some issues during experimentation, the final product was most likely assembled correctly, as the LPS-specific antibodies recognized it. Despite the lack of bacterial opsonization by the generated antibodies, their specificity suggests that the antigenic presentation was successful, primarily targeting the protein component. If the candidate is confirmed to offer protection in an animal model of periodontosis, the design of future vaccines could be performed faster and more safely for many other pathogens.

Data availability statement

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27960216.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.