Abstract

Background. Resveratrol (RSV) exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, antiaging, and cardioprotective properties. However, due to its hydrophobic nature, it is prone to instability and oxidation, which significantly limit its biomedical applications.

Objectives. The aims of this study were: 1) To prepare and characterize hydrogels and micelles by mixing the synthesized PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM copolymer and RSV in an aqueous environment; 2) To investigate the molecular interactions between the polymer and RSV; 3) To evaluate various properties of the polymeric micelles and hydrogels; 4) To determine the efficiency of RSV release from the polymeric micelles.

Materials and methods. A well-defined PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM block copolymer was synthesized and purified. Gel permeation chromatography and 1H NMR were used to characterize the chemical composition and molecular weight of each copolymer. The encapsulation of RSV and its interaction with PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM were confirmed using 2D nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY). The lower critical solution temperature (LCST), critical micelle concentration (CMC) and structure of the polymeric micelle were characterized using surface tension measurements, a viscometer, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The rheological behavior of the RSV-loaded hydrogels was also investigated.

Results. The results showed that the RSV-loaded micelles were successfully prepared. The LCST and CMC of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM polymeric micelles were determined to be 35°C and 0.005 g/L, respectively. The micelles have a spherical profile with a particle size of 100 nm and a narrow size distribution.

Conclusions. Resveratrol can be encapsulated within polymeric micelles formed by PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM block copolymer below the LCST. Its molecules are incorporated into the hydrophobic domains of poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PNIPAM), forming a molecular complex. The point of molecular interaction is primarily at the phenolic region of RSV. Below LCST, PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM behaves as a polymeric surfactant at low concentrations and as an associating polymer at high concentrations. At high polymer concentrations, PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM formed a hydrogel. Above LCST, it was released from the polymeric micelles.

Key words: resveratrol, drug release, polymeric micelle

Background

Cartilage regeneration is an important and innovative procedure for replacing damaged knee cartilage.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Due to the increasing aging population, there is a growing need for cartilage regeneration. Current methods include autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI).1 In this method, healthy cartilage cells are taken from the damaged knee and cultured in a lab for several weeks. They are then injected into the damaged joint to regenerate the cartilage along with the surrounding tissue. Although various therapeutic methods have been established, there remains a challenge in achieving cartilage regeneration with normal anatomy, morphology and function. Moreover, repaired cartilage often lacks sufficient mechanical properties, leading to further degeneration. These problems could potentially be solved by the application of hydrogels, which are commonly used as scaffolds for cartilage repair.6, 7

Resveratrol (RSV, 3,5,4’-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a natural phenol found in grape skins, blueberries, raspberries, peanuts, and other plants. It is anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, antiaging, and cardioprotective.8, 9, 10, 11 Importantly, RSV has been reported to suppress the interleukin (IL)-1b-induced inflammatory signaling pathway, making it a promising drug for potential arthritis therapies.12, 13, 14, 15 However, due to its instability under light and heat, as well as its susceptibility to oxidation, the biomedical applications of RSV are limited. Because RSV is a hydrophobic drug, one approach to overcome these challenges is designing an RSV-controlled release system via encapsulation to improve drug administration and therapy efficiency. Encapsulation is considered the most promising way to deliver hydrophobic drugs such as RSV. The primary strategy of encapsulation aims at incorporating a hydrophobic core material into a hydrophilic shell to facilitate the delivery of active agents or drugs into living cells.16, 17 Therefore, an encapsulated system with RSV as the core and biocompatible materials as the shell will not only enhance water solubility of RSV, but also increase its stability by improving photo-stability and resistance against oxidation, thereby enhancing its bioavailability during drug administration.

Stimuli-responsive hydrogel systems are unique due to their high swelling capacity and ability to undergo gelation. These hydrogels can change their appearance or physical properties in response to environmental stimuli such as pH, temperature and light.18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Several thermoresponsive polymers form a gel-like material at temperatures higher than the lower critical solution temperature (LCST).23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Some thermosensitive hydrogels shrink below and dissolve above the upper critical solution temperature (UCST). Typically, thermoresponsive hydrogels consist of a hydrophilic polymer network. Many studies have shown that the gel formation process involves cross-linking of molecular chains through intermolecular interactions (van der Waals forces, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, etc.) rather than chemical reactions. A change in ambient temperature can affect these interactions, causing the hydrogel to form in aqueous solution through a simple reversible phase transition (sol–gel). Therefore, the preparation of thermoresponsive hydrogels is straightforward and does not require organic solvents, which is advantageous for delivering hydrophobic drugs. Some studies have shown that thermosensitive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-block-poly(ethylene oxide)-block-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM) hydrogels exhibit ideal gel properties, capable of loading protein drugs below 30°C and undergoing a sol–gel phase transition at human body temperature.23 The PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM hydrogel has been noted for its good biological degradation and safety.24, 25, 26, 27 However, it still has some unresolved issues such as the need for drug loading at lower temperatures and a short sustained-release cycle (only 7 days) for protein drugs, which limits its clinical application. In addition, an increase in PNIPAM block length can lead to the aggregation of protein drugs.

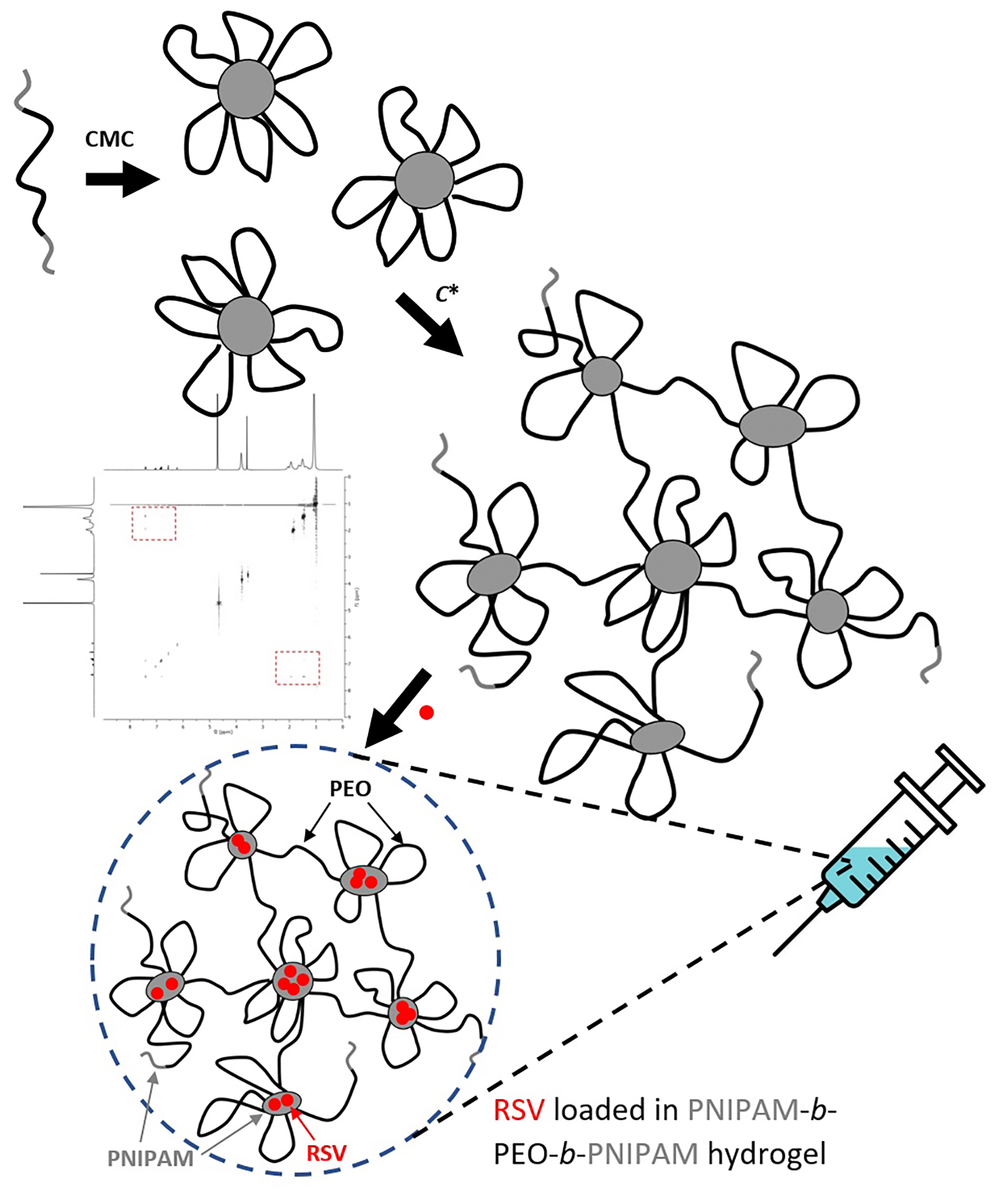

In this study, a thermosensitive PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM polymer was synthesized and used as a drug carrier for RSV. Above the LCST, PNIPAM segments become water-insoluble, resulting in the formation of hydrogel with a 3D polymeric network. Hydrophobic junctions within this network, formed by PNIPAM molecules, allow for the loading of RSV molecules. Below the LCST, PNIPAM becomes soluble in aqueous solutions, causing the hydrogel network to collapse and release the RSV molecules. The polymeric structure and incorporation of RSV into PNIPAM junctions were characterized using 2 NMR techniques. Additionally, the critical micelle concentration (CMC) was determined with surface tension. The rheology of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM above the overlap concentration (C*) and the micellar shape, particle size, distribution of the drug within micelles below C*, and in vitro release properties were investigated.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to design a thermo-induced polymeric hydrogel as a potential carrier for RSV-loaded micelles and injectable hydrogels through: 1) characterizing the chemical structure of the synthesized block copolymer; 2) preparing and characterizing hydrogels and micelles by mixing the synthesized copolymer and RSV in an aqueous environment; 3) investigating the molecular interaction between the polymer and RSV; 4) evaluating various properties of the polymeric micelle and hydrogel; and 5) determining the efficiency of RSV release from the polymeric micelle.

Materials and methods

Materials

Resveratrol (98%) was purchased from Innochem Co Ltd (Beijing, China). The N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAM) monomer (Mn~113 g/mol, 98%) and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) (Mn~200,000 g/mol) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Ce(IV) ammonium nitrate (Ce(NO3)6(NH4)2) was provided by Wako Pure Chemical Co (Osaka, Japan). All experiments used deionized water obtained from the Millipore-Q water purification system (Merck Millipore, St. Louis, USA). The NIPAM monomer was purified by recrystallization from n-hexanes 3 times, while the PEO was purified by dissolving it in dichloromethane and precipitating it in diethyl ether. This purification process was repeated 3 times. Ce(IV) ammonium nitrate was dried at 105°C in a vacuum oven and dissolved in a 1 N aqueous solution of HNO3 to give a 0.1 M aqueous solution of Ce4+ ions. Other chemicals were used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM

The synthesis procedure was conducted as follows: PEO was dissolved in 20 mL of Milli-Q water in a 200 mL flask and degassed for 2 h under a gentle flow of pure N2. Ce4+ solution was then added to give a Ce4+/PEO molar ratio of 5:1. After stirring this solution for 10 min at 70°C, NIPAM dissolved in 15 mL of Milli-Q water was added under a nitrogen atmosphere. The polymerization was carried out under N2 at 70°C for 1 h. Upon completion of the polymerization, the solution temperature was reduced to room temperature and dialyzed against Milli-Q water for 3 days using a regenerated cellulose bag with a molecular weight (MW) cutoff of 3,000 g/mol.

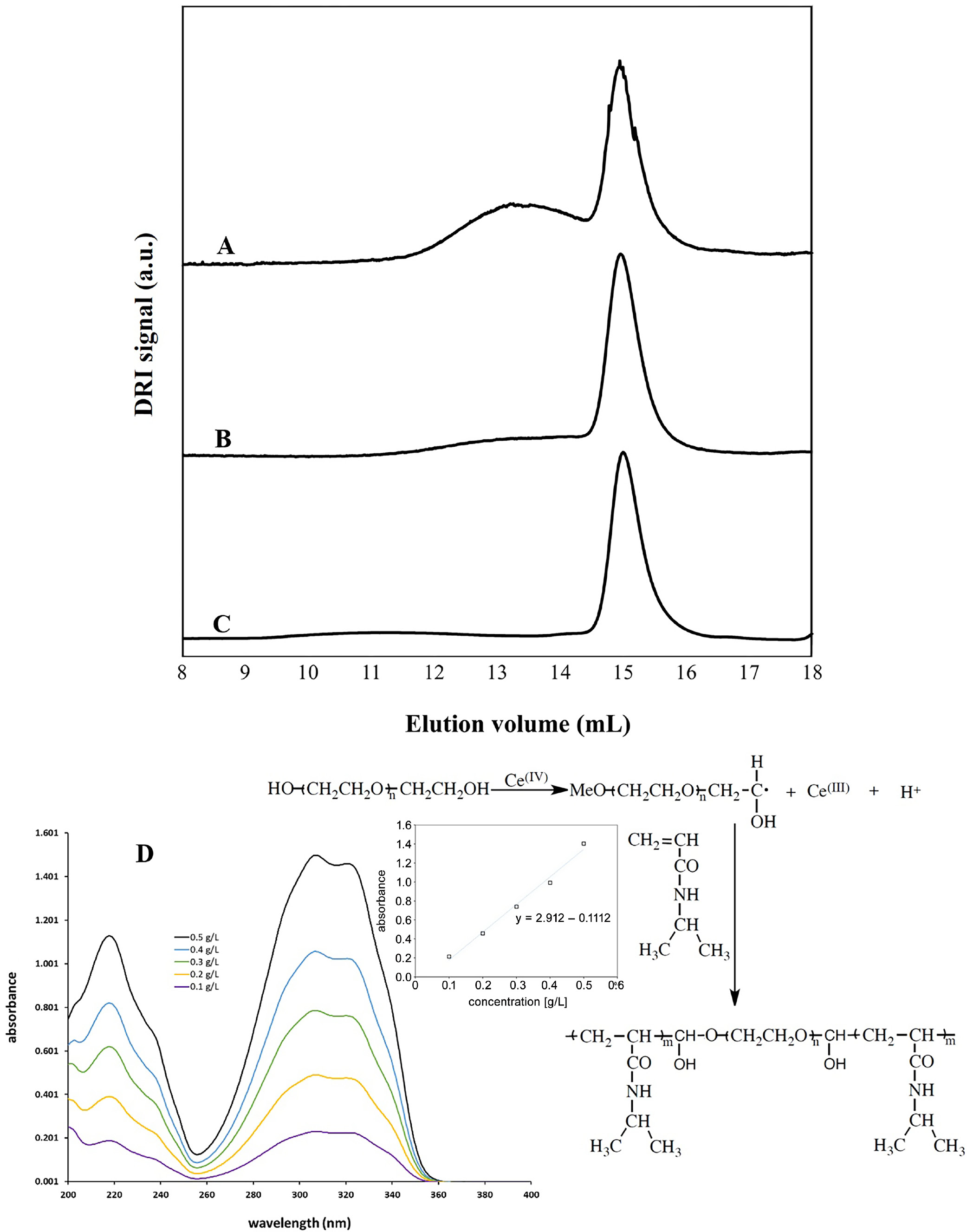

The Ce4+ and NIPAM solutions were degassed with nitrogen and transferred into the PEO solution using a syringe. Polymerization was carefully conducted to minimize oxygen exposure. Ce4+, NIPAM and PEO solutions were placed in separate round-bottom flasks and degassed for 2 h using nitrogen. The solutions were then transferred with a cannula into the reaction vessel, where polymerization took place. Using high-purity nitrogen from Praxair (Xi’an, China; Ultra High Purity 5.0) improved the polymerization of NIPAM. The synthesis scheme for PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM is shown in Figure 1.

The resulting product was dissolved in a 2 M NaNO3 aqueous solution to achieve a 20 wt% solution, which was transferred into an ice bath to ensure complete dissolution. Centrifugation was performed using a Beckman Coulter Avanti J-301 centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA) at 40°C and 8,000 rpm for 60 min. The precipitate was recovered and fully dried with a Labconco Freezone 6 freeze dryer (Labconco, Kansas City, USA) before conducting gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and NMR analyses. Centrifugation was repeated until GPC and NMR data confirmed the absence of unreacted PEO. Excess salts were removed by dialysis against Milli-Q water for 3 days using a regenerated cellulose bag with an MW cutoff of 3,000 g/mol.

High-resolution 1H NMR spectra of the samples were obtained using a 400 MHz Bruker NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, USA), with deuterated water (D2O) as the solvent. The GPC device (Agilent 1260 series; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) consisted of a single pump and multi-detector systems, including a light scattering detector, a refractive index detector and a viscosity detector.

Determination of the LCST by turbidimetry, absorbance and viscosity

Turbidimetry measurements were conducted using a DataPhysics MS-20 optical dispersion stability analyzer (DataPhysics Instruments, Filderstadt, Germany) at 0.5°C intervals from 25°C to 40°C. The polymer solution was prepared by dissolving 0.02 g of homopolymer PNIPAM (Sigma-Aldrich; MW = 20,000 g/mol) in 10 mL of Milli-Q water. Absorbance measurements were conducted using the BK4200 UV-vis spectrophotometer (Shanghai Huicheng General Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for a PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM solution at a concentration of 10 g/L mixed with RSV. The temperature was increased in 0.5°C increments from 25°C to 40°C. Viscosity measurements were conducted using a stress-controlled rheometer (Paar Physica DSR 4000; Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria), with zero-shear viscosity (η0) used as the viscosity data. The temperature was increased in 0.5°C increments from 25°C to 40°C.

Preparation of RSV-loaded polymeric micelles

Briefly, 0.4 g of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM polymer and 0.01 g of RSV were accurately weighed and dissolved in 4 mL and 1 mL of dimethyl formamide (DMF), respectively. After mixing and stirring for 1 h, the solution was loaded into a dialysis bag and dialyzed against 120 L of deionized water for 2 days. The turbid solution obtained from dialysis was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was filtered using a nylon membrane with a pore diameter of 0.15 μm to remove RSV not encapsulated by micelles. The RSV-loaded micelles were obtained by freeze-drying the filtrate.

Characterization of micelle size, profile and structure

The average particle size and distribution of the polymeric micelles were determined using light scattering spectroscopy at 25°C and a wavelength of 486 nm, with a scattering angle set to 90°. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used (Hitachi-HT7700; Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to observe the morphology and profile of the micelles. The freeze-dried micelle suspension was dropped onto a copper surface. Phosphotungstic acid (0.1% mass fraction) was used for staining, and the morphology was observed under a lens after drying.

Rheology

Rheological behaviors were investigated using a stress-controlled rheometer (Discovery HR-2; TA Instruments, New Castle, USA) Solutions with viscosities greater than 100 Pa·s were tested using a parallel plate geometry with a 25-mm diameter plate, whereas samples with viscosities below 200 Pa·s were analyzed using a double wall concentric cylinder setup. All experiments were performed at 25 ±2°C. Experimental data were recorded within the range of sensitivity for the rheometer based on the specifications provided by the instrument manufacturer. Angular frequency sweep experiments were conducted under conditions of linear viscoelasticity, where both Gʹ and Gʹʹ values remained unchanged with applied stress. The angular frequency interval ranged from 0.01 rad/s to 1,000 rad/s. Various frequency intervals were applied to different sample solutions to ensure that viscoelastic responses were within the sensitivity range of the rheometer, as described in the instrument manual. For the acquisition of viscosity profiles, solutions were subjected to shear with a shear rate ranging from 0.0001 s−1 to 100 s−1.

Standard curve of UV spectra of RSV

Resveratrol was dissolved in ethanol to prepare a standard stock solution at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. To construct the standard curve, a series of RSV solutions with different concentrations in ethanol were prepared. Ultraviolet–visible (UV-vis) spectra of samples at various RSV concentrations were obtained using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Shanghai Huicheng General Instrument Co., Ltd.).

Morphology observation

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Hitachi-SU8000; Hitachi Ltd.) and TEM were utilized to observe the morphological structure of polymeric micelles. The solutions were frozen with liquid nitrogen and coated with a thin layer of gold for 60 s at 40 W under vacuum to ensure the electrical conductivity of SEM samples. An excitation voltage of 10 kV was applied for all SEM images.

In vitro release of RSV from polymeric micelles

Two samples (26 mg each) of lyophilized polymeric micelles were accurately weighed and loaded into separate dialysis bags. The lyophilized micelles were dissolved with 5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.5). Each dialysis bag was sealed and immersed in 25 mL of sodium salicylate solution (1 mol/L) and phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) for an in vitro release experiment conducted in a water bath shaker at 35°C. The solution outside the dialysis bags was replaced with fresh solution of equal volume at set time intervals; the displacement was 10 mL. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity; Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) was used to detect the content of RSV in the released solution. The cumulative release amount was calculated using Equation 1:

(1)

(1)

where Er% represents the cumulative release amount of RSV in %; Ve is the displacement volume in mL (10 mL); V0 is the volume of released solution in mL (30 mL); mi is the mass concentration of RSV at the ith sampling in μg/mL; mp is the mass of RSV in the loaded polymeric micelles in μg; and n is the displacement number.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM

Several attempts were made to synthesize PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM. Initially, the polymerization yielded PNIPAM blocks with a high MW of 12,000 g/mol, albeit with a low overall yield. Although the exact yield was not quantitatively determined, it was qualitatively estimated by examination of the GPC experiments. Depending on the polymerization conditions, the ratio of peak intensity to shoulder decreased, indicating an increase in polymerization yield. Using the high-purity nitrogen, the yield was further increased. After degassing the polymerization vessel with high-purity nitrogen, a significantly higher MW product was obtained, as evidenced by a substantial increase in the signal of crude product. The GPC curves for various attempts are shown in Figure 1A–C. Analysis of the GPC trace using light scattering and differential refractometer (DRI) detectors revealed a MW of 242,000 g/mol and a polydispersity index (PDI) of 1.43.

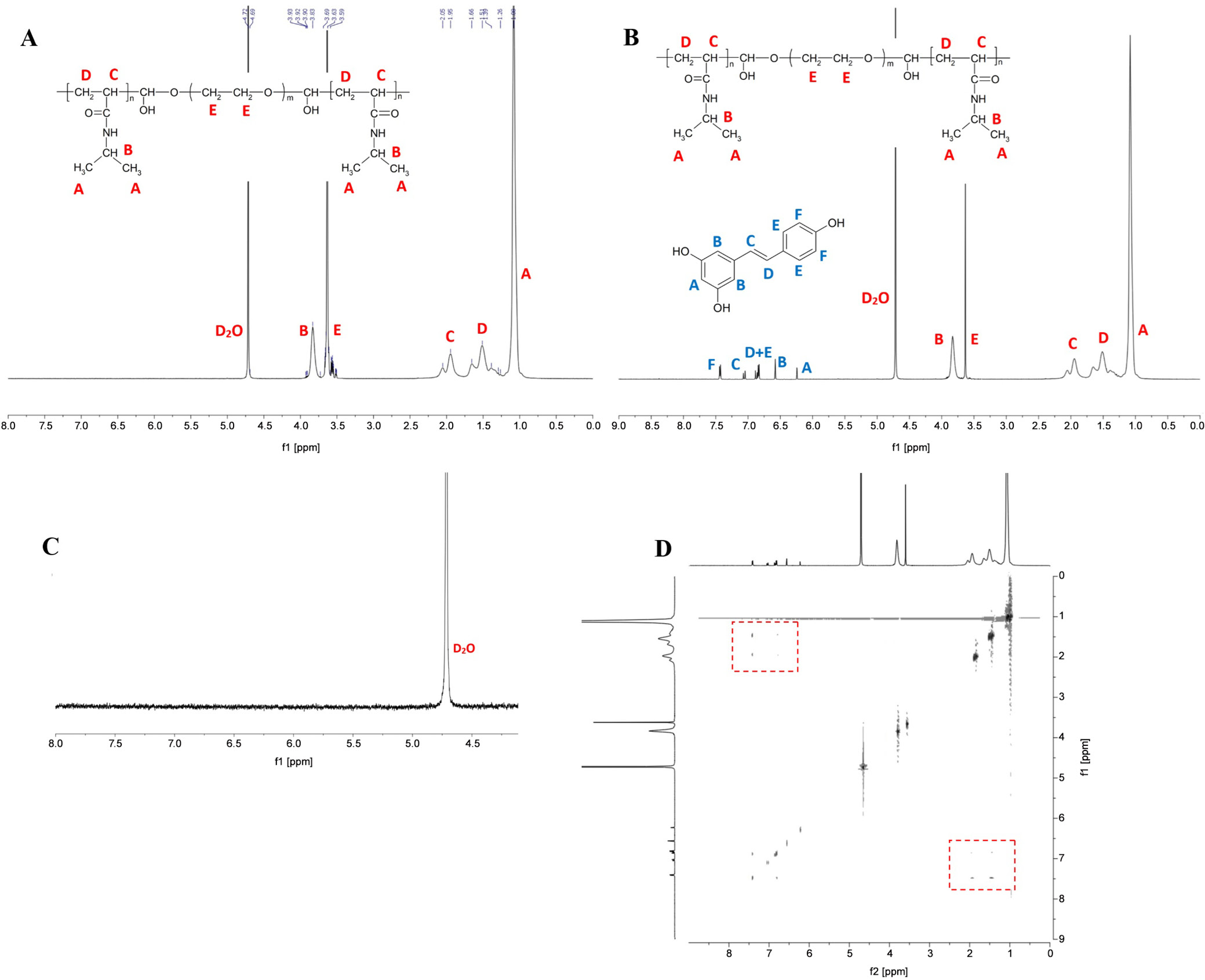

The 1H NMR spectrum in Figure 2A shows assignments for all protons found in the chemical structure of the copolymer sample. Resveratrol was loaded into the polymeric micelle, and the 1H NMR spectrum in Figure 2B shows the chemical shifts of the protons from the RSV molecule. In contrast, Figure 2C shows that RSV in D2O without the polymer did not exhibit any peaks because RSV is highly hydrophobic.

To investigate the interaction and incorporation of RSV into PNIPAM hydrophobic junctions below the LCST, 2D nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments were conducted, and the results are shown in Figure 2D. In the spectra, there were some signals at the intersections of the peaks from RSV and the PNIPAM blocks, suggesting nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) or proximity within 0.5 nm between protons of PNIPAM and the RSV molecule. Notably, Figure 2D also indicates an interaction between the PNIPAM main chain and the RSV aromatic ring bearing 1 hydroxyl group, suggesting that the point of molecular interaction might be at the phenolic part of RSV.

Determination of CMC and C*

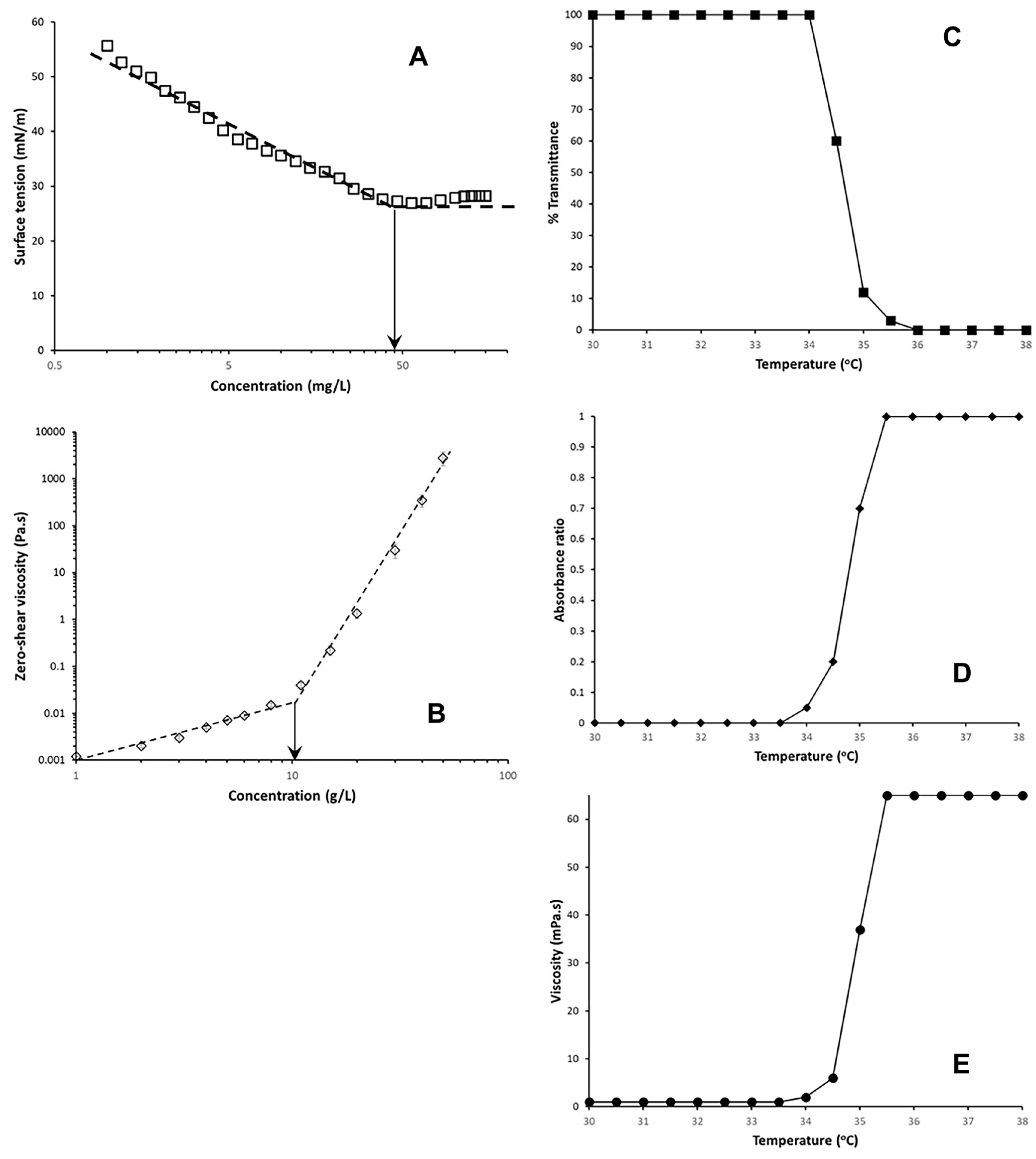

Critical micelle concentration defines the concentration at which a surfactant or polymeric surfactant begins to form micelles. Above CMC, the concentration of free surfactant remains unchanged because additional surfactant molecules will only form more micelles. At CMC, the interface becomes saturated with surfactant molecules, resulting in constant surface tension with increasing surfactant concentration. Figure 3A shows the change in surface tension with increasing polymer concentration of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM at 25°C, with CMC determined to be 45 mg/L from the cross point of 2 fits with different slopes.

At C*, polymer chains begin to overlap and intermolecular interactions occur. This leads to a sharp increase in solution viscosity due to polymer chain entanglement for water-soluble polymers and hydrophobic association for associating polymers such as PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM below LCST. Figure 3B shows a plot of viscosity versus polymer concentration of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM at 25°C, with C* determined to be 10.1 g/L from the cross point of 2 fits with different slopes.

Determination of the LCST

The LCST of PNIPAM homopolymer and PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM block copolymer were determined using a UV-vis spectrophotometer and rheometer. Below the LCST of PNIPAM, the solution remains clear and transmits light at 486 nm with 100% transmission. As the temperature of the solution increases past the LCST of PNIPAM, phase separation occurs, the solution becomes turbid, and light transmission drops to 0%. This behavior is illustrated in Figure 3C for the PNIPAM homopolymer.

For the LCST determination of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM, RSV was mixed with the polymer solution at a concentration of 1 g/L. Below the LCST, PNIPAM segments are water-soluble, and hydrophobic RSV is released into the water, resulting in undetectable absorbance in the bulk solution and an absorbance ratio of zero. Above the LCST, PNIPAM becomes hydrophobic, and RSV dissolves in the hydrophobic core of the polymeric micelle. The absorbance at 307 nm matches that acquired with an equivalent amount of RSV in ethanol, resulting in an absorbance ratio of 1, as shown in Figure 3D.

At a higher concentration (10 g/L) of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM, the entire polymer chain is water-soluble below the LCST (Figure 3E). Above the LCST, an associating polymer network forms to increase solution viscosity.

Using the above methods, results are presented in Figure 3C–E. The LCST of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM was determined to be 34.5°C, compared to 35°C for PNIPAM homopolymer.

Rheology and viscoelasticity

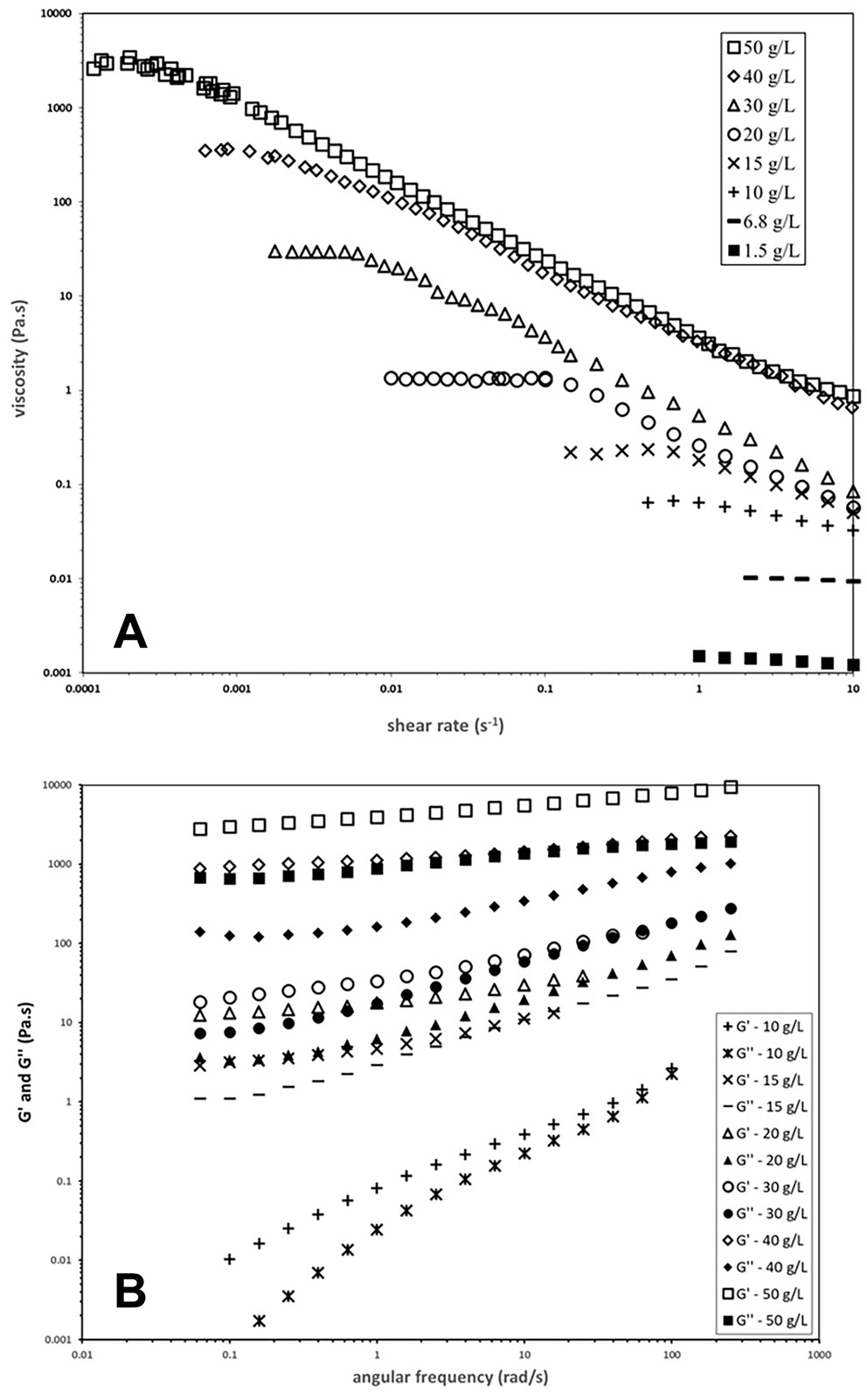

Figure 4A shows the steady-shear viscosity profiles as a function of shear rate obtained from aqueous solutions of the block copolymer at various concentrations above LCST. A Newtonian region was observed for all samples at lower shear rates, indicating constant viscosity regardless of shear rate. These viscosity values in the regimes are denoted as η0 and represent the viscosity of the samples under no shear. Figure 4A demonstrates that increasing the block copolymer concentration from 1 g/L to 50 g/L significantly increased the solution viscosity by 106-fold, from 1 mPa·s to 2,000 Pa·s. These results suggest that above LCST, the PNIPAM segments become highly hydrophobic, facilitating efficient polymeric network formation through hydrophobic association. Figure 4A also shows that the viscosity significantly decreased, with an increase in shear rate when a shear force was applied to the sample solution. This phenomenon is defined as shear thinning, which is commonly observed in aqueous solutions of hydrophobically modified water-soluble polymers, and it has been widely studied in previous publications. Shear thinning typically results from a transition of inter-molecular hydrophobic associations to intra-molecular associations via the processes of “pull-out” and the rearrangement of hydrophobic units. Figure 4A shows significant shear thinning at lower onset shear rates for samples with higher viscosity, suggesting that this transition occurs more easily in polymer solutions with higher viscosity.

Figure 4B shows the G’ and G’’ results as a function of ω for PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM block copolymer solutions at various concentrations below LCST. Solutions above 40 g/L exhibited characteristic viscoelastic behavior resembling gels. At a concentration of 50 g/L, the G’ and G’’ values changed only slightly with ω, and all G’ values remained higher than G’’ values, suggesting the dominance of sample elasticity over the sample’s viscous flow. Consequently, PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM at 50 g/L formed a physical gel in water via the hydrophobic association of PNIPAM segments.

Characterization of RSV-loaded polymeric micelles

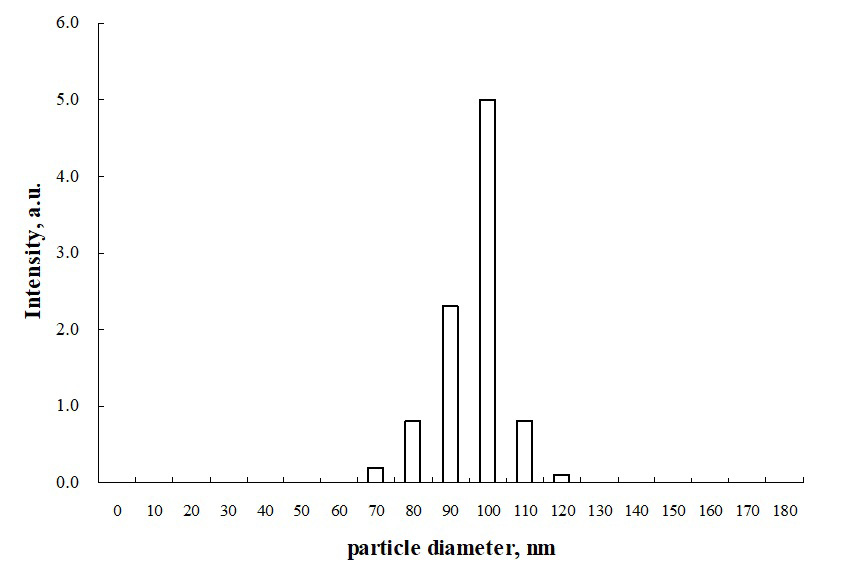

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments were conducted to measure the particle size distribution of resveratrol (RSV)-loaded polymeric micelles. Figure 5 shows the average diameter of micelles with 6.2% drug loading content (mass fraction). As seen in Figure 5, the micelle diameter is approx. 100 nm, and the particle size distribution is relatively narrow.

The same method was used to measure the particle size of RSV-loaded micelles with different drug dosages; the obtained data are listed in Table 1. With an increase in RSV content, the size of polymeric micelles also slightly increased due to more drugs being loaded into the micelles, expanding the hydrophobic core of the polymeric micelle accordingly. At 16.5% RSV content, the micelle size changed significantly, likely due to exposure of a small amount of drugs to the aqueous environment, leading to secondary aggregation of micelles. The encapsulation efficiency of drug-loaded micelles prepared by the dialysis method was low, possibly due to the penetration of a small amount of RSV into the organic solvent from the dialysis bag during dialysis.

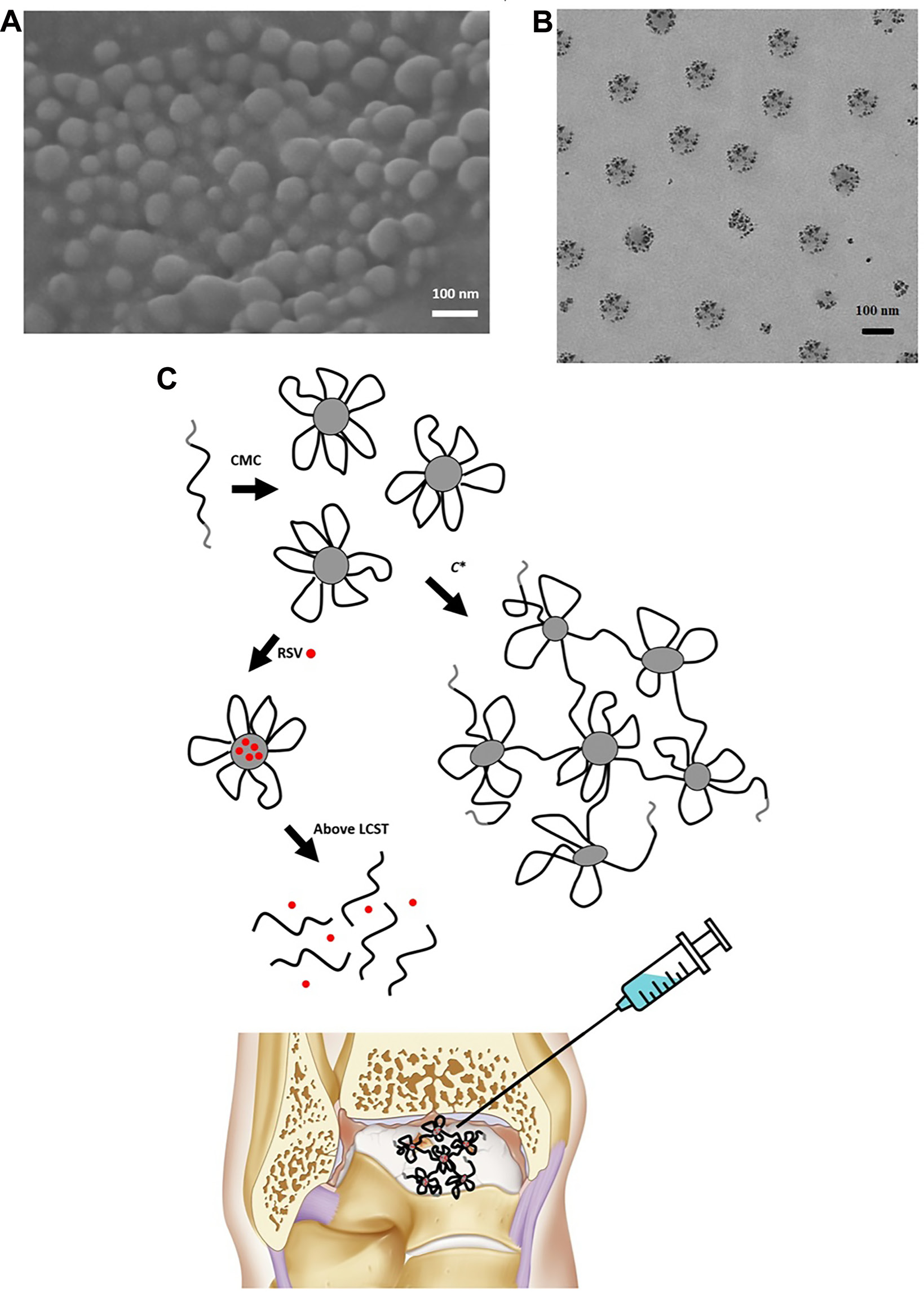

Figure 6A,B presents TEM images of the RSV-loaded polymeric micelles. Generally, the RSV-loaded micelles exhibit a spherical profile with an obvious core-shell structure, and the particle size is relatively uniform (around 100 nm), consistent with the results obtained using the DLS method.

Mechanisms of RSV-loaded polymeric micelles and hydrogel

As shown in Figure 6C, an injectable RSV delivery system was developed by combining RSV-loaded PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM copolymer micelles with an in situ forming hydrogel at a high polymer concentration. This approach enhances the stability and retention time of the drug, thereby promoting the performance of cartilage regeneration. Below the CMC of 45 mg/L, the polymer exists as single chains. Above the CMC and the LCST, the PNIPAM blocks become hydrophobic, facilitating the formation of polymeric micelles with hydrophobic domains that accommodate the hydrophobic RSV molecules. As the concentration exceeds C* = 10 g/L, a 3D polymeric network forms, increasing solution viscosity; a physical gel forms above 40 g/L. Below the LCST (34.5°C), the PNIPAM blocks become hydrophilic or water-soluble, causing the collapse of either the micellar structure or the polymeric network, thereby releasing RSV. Given that human body temperature exceeds the LCST of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM block copolymers, RSV can be injected in vivo in the form of a hydrogel. Following injection, RSV will target damaged cartilage for repair and regeneration.

Discussion

Resveratrol is a hydrophobic drug. Theoretically, it can be encapsulated into a micellar system in an aqueous environment to establish a controlled release system for delivering RSV to a target site. However, such a system has never been studied or reported for RSV. Previous publications have successfully applied PNIPAM-based hydrogels for the delivery of various drugs, such as levofloxacin,28 chemokine SDF-1 alpha,29 melatonin,30 ciprofloxacin,31 doxorubicin,32, 33, 34 ibuprofen,35 and so on. These well-designed PNIPAM-based hydrogel systems have exhibited excellent behavior in drug delivery. Because all of the abovementioned drugs have properties similar to RSV, this study investigated the feasibility of using a PNIPAM and PEO-based hydrogel to deliver RSV. It demonstrated that RSV can be encapsulated into micelles formed by PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM below the LCST. Structural characterization of the complex indicated the specific position of RSV within the micelle, which is very important for molecular modeling and potential chemical modifications to improve the drug-loading performance. Resveratrol molecules insert themselves into the interior parts of PNIPAM hydrophobic domains to form a molecular complex. The methyl groups of PNIPAM and the resorcinol part of RSV are not involved in this complex because the aromatic structure is more compact and hydrophobic than linear alkyl chains. The π–π stacking interactions are easily formed between the conjugated structures of the aromatic ring. Polymeric surfactants containing aromatic structures may have a stronger interaction with RSV and could be used to encapsulate more RSV molecules compared to PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM.

The synthesized copolymer demonstrated a clear LCST. Below this temperature, PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM behaves like a polymeric surfactant at low concentrations and like an associating polymer at high concentrations. Above 50 g/L, the polymer formed a hydrogel through the hydrophobic association of PNIPAM segments. Resveratrol molecules can be loaded into the hydrogel for in vivo injection. After injection into an environment above the LCST, PNIPAM switches to a hydrophilic state to release the drugs. According to the results presented in Table 1, a large fraction of RSV was released from the polymeric micelle above the LCST, indicating significant potential for RSV delivery and release from this injectable hydrogel formulation.

Limitations

The effectiveness and performance of the RSV-loaded injectable formulation in the current study may be limited by in vitro experiments. Therefore, future studies should include in vivo experiments using experimental animals.

Conclusions

In this study, a thermo-responsive block copolymer consisting of a PEO main chain end-capped with PNIPAM blocks was synthesized for the preparation of RSV-loaded polymeric micelles and injectable hydrogels. The chemical structure of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM was confirmed using 1H NMR. The incorporation of RSV into the hydrophobic cores of polymeric micelles was confirmed with 2D NOESY, suggesting that RSV molecules associate with the interior of PNIPAM hydrophobic domains to form the molecular complex. However, the methyl groups of PNIPAM and the resorcinol part of RSV are not involved in this complex. The GPC results yield a polymer with MW of 242,000 g/mol and a PDI of 1.43. The CMC, C* and LCST of PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM are 45 mg/L, 10.1 g/L and 34.5°C, respectively. We observed that the PNIPAM-b-PEO-b-PNIPAM solution exhibits a non-Newtonian plateau at very low shear rates, but at higher shear rates, the viscosity drops dramatically. The polymer at 50 g/L forms a physical gel in water due to the hydrophobic association of PNIPAM segments. The RSV-loaded micelles were successfully prepared; they exhibit a spherical profile and a particle size of 100 nm with a narrow size distribution.

In summary, this RSV-loaded hydrogel system prepared using thermal-responsive copolymers shows potential as an injectable formulation for delivering and releasing RSV for cartilage tissue regeneration.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.