Abstract

Background. Few studies have focused on the relationship between the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) and the prognosis of elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Objectives. This study aimed to evaluate the predictive value of the SIRI for predicting 3-year outcomes in patients >60 years old after stent implantation and to assess variables associated with SIRI.

Materials and methods. A total of 1,758 patients with ACS who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were enrolled and divided into an older group (n = 960) and a younger group (n = 798) using a cutoff of >60 years. Major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) including all-cause death, nonfatal acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and nonfatal stroke were recorded.

Results. During follow-up, 165 patients experienced 1 or more MACEs. Patients in the older group had a greater incidence of recurrent MACEs and mortality than those in the younger group. The SIRIs were significantly greater in the older group. Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that the level of the SIRI was significantly associated with age, hypertension, diagnosis of AMI, number of diseased vessels, and platelet count. The SIRI was an independent predictive risk factor for MACEs in patients >60 years old. Similar relationships between the SIRI and MACEs were also observed in ACS patients with and without AMI.

Conclusions. The SIRI was an independent predictive risk factor for MACEs in patients aged >60 years with ACS and ACS with or without AMI after stent implantation during 3 years of follow-up. The SIRI can be used as an indicator for identifying high-risk patients for intensive therapy to further reduce MACEs in the PCI era.

Key words: acute coronary syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, major adverse cardiac event, systemic inflammation response index, elderly patients

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the leading causes of cardiovascular death in developing and developed countries. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a critical type of coronary artery disease that includes unstable angina and ST-segment elevation and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions. It is commonly caused by the rupture of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques and thrombus formation, leading to the reduction or cessation of coronary blood flow.1, 2, 3 Due to improved drug therapy and early revascularization, the mortality rates for ACS patients have decreased significantly over the past decades.4 However, patients who survive ACS still have worse outcomes and a higher risk for recurrent major adverse cardiac events (MACEs).5, 6 Elderly patients often seem more likely to experience increased rates of MACEs.7 These patients are consequently more fragile and have a greater incidence of comorbidities.8 The prognosis may improve through accurate risk stratification and intensive therapy for elderly patients.

It is well known that ischemic heart disease caused by CAD is an inflammatory disease of the arteries.9 The immune-inflammatory system is involved in every step of artery wall injury, lipid accumulation, fibrous cap formation, plaque rupture, and clot formation in ACSs.3, 10, 11 As markers of inflammation, white blood cell (WBC) counts, such as neutrophil, lymphocyte and monocyte counts, and their derived indicators are often used to predict the risk of poor outcomes in patients with CAD.12, 13 Recently, the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) has emerged in several clinical practices as novel indicator of the balance between inflammation and the immune response.14, 15 The SIRI, which employs 3 blood cell subtypes (neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes), is related to a heightened risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke and all-cause death in the general population,16 and atrial fibrillation in patients with ischemic stroke.17 The SIRI was significantly greater in patients with ACSs than in those without ACSs and was associated with the severity of CAD.15 However, few studies have focused on the association between the SIRI and the prognosis of elderly patients surviving an ACS. The present study hypothesized that the SIRI is an independent risk factor for MACEs in elderly patients with ACS after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Objectives

This study aimed to explore the predictive value of the SIRI on the 3-year outcomes of patients older than 60 years after stent implantation and to evaluate variables associated with the SIRI. Further subgroup analyses were performed to detect associations between the SIRI and MACEs in ACS patients with and without AMI.

Materials and methods

Patients

This retrospective study was conducted at Tangshan Gongren Hospital, China. From November 2018 to October 2019, 1,758 patients with ACS (unstable angina or ST-segment elevation or non-ST-segment elevation MI) who were consecutively admitted to the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine and who underwent primary or selective PCI (primary PCI for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or selective PCI for ACS patients without AMI) were enrolled in the study. The diagnosis of unstable angina followed the 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of ACSs in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation.18 The participants were divided into younger (n = 798) and older (n = 960) groups according to age (≤60 years or >60 years). The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) severe renal or liver disease; 2) a history of malignancy; 3) pneumonia, periodic fever, rheumatic disease, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematous, myeloma, or any disease affecting WBC counts; and 4) lack of follow-up.

Clinical data

The traditional risk factors included age, sex, height, weight, smoking status, history of previous MIs, diabetes, primary hypertension, and dyslipidemia. The medications included oral aspirin, clopidogrel/ticagrelor, statins, β-receptor blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEIs/ARBs). Other factors included heart rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) on admission. Venous blood samples were also obtained on admission to measure WBC subtypes, and platelet counts were measured with an autoanalyzer DxH 900 (Beckman Coulter K.K., Tokyo, Japan). The SIRI was calculated as (neutrophils × monocytes)/lymphocytes. The levels of cholesterol, triglycerides and lipoprotein were measured after overnight fasting using routine automated laboratory analyzers (AU5800; Beckman Coulter; Brea, USA). All participants provided written informed consent, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tangshan Gongren Hospital (approval No. GRYY-LL-KJ2022-101). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Coronary angiography

All patients received coronary angiography to determine the number of diseased coronary arteries and culprit vessels. Percutaneous coronary intervention procedures were performed by an experienced teamat a high-volume centerwith a 24-h invasive service. A successful procedure was defined as target vessel residual stenosis <30% and thrombolysis in MI grade 3 flow. Aspirin, clopidogrel/ticagrelor, statins, ACEIs/ARBs, and β-receptor blockers were used according to guidelines.

Follow-up and outcomes

Patients underwent regular follow-ups at 1 month after stent implantation and every 6 months thereafter. Data were obtained from medical records and/or telephone calls with family members of patients made by independent reviewers. The MACEs were defined as nonfatal AMI, nonfatal stroke and all-cause death. Stroke was defined as a combination of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.

Statistical analyses

Numerical variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (±SD) and were compared using a Student’s t-test. The enumeration data were compared using the χ2 test. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to determine the significance of the relationships between the SIRI and age, sex, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), history of previous MI, diabetes mellitus, primary hypertension, dyslipidemia, diagnosis of AMI, number of diseased vessels, and platelet count. A curve-fitting method was applied to explore the relationship between the SIRI and MACEs in the older group. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the hazard ratios of MACEs after adjusting for all variables in the older group, AMI subgroup and non-AMI subgroup. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS v. 22.0 software package (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The p-value was set at 0.05 to indicate a statistically significant difference and was two-tailed.

Results

Clinical endpoints

The median follow-up duration was 38 months (7–44 months). Among the 1,758 patients, 729 (76%) were men, and the average age was 60 ±11 years. There were 165 patients who experienced 1 or more adverse clinical events. The details of the MACEs in the 2 groups are listed in Table 1. Patients in the older group had an increased incidence of recurrent MACEs (11.2% compared to 7.1%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, mortality was significantly lower in the younger group than in the older group.

Characteristics of elderly patients

The comparisons of characteristics between the 2 groups are listed in Table 2. Older patients were more likely to have lower BMI and blood lipid levels and were less likely to use ACEIs/ARBs and β-blockers as medications (p < 0.05). Female sex, hypertension and previous myocardial infarctions were more prevalent in the older group (p < 0.005). Smoking status, dyslipidemia and a diagnosis of AMIs were more common in the younger group (p < 0.05). No significant differences were found in the LVEF or percentage of patients with 3-vessel coronary disease (p > 0.05). Remarkably, compared with those in the younger group, the SIRIs were significantly greater despite the absolute counts of leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes being significantly lower in the older group (p < 0.05).

SIRI-related factors

Multiple linear regression analysis was employed to detect potential factors affecting the SIRI. Multiple linear regression (analysis of variance (ANOVA) F = 41.985; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.209) revealed that the SIRI was significantly associated with age, hypertension, diagnosis of AMI, number of diseased vessels, and platelet count (Table 3).

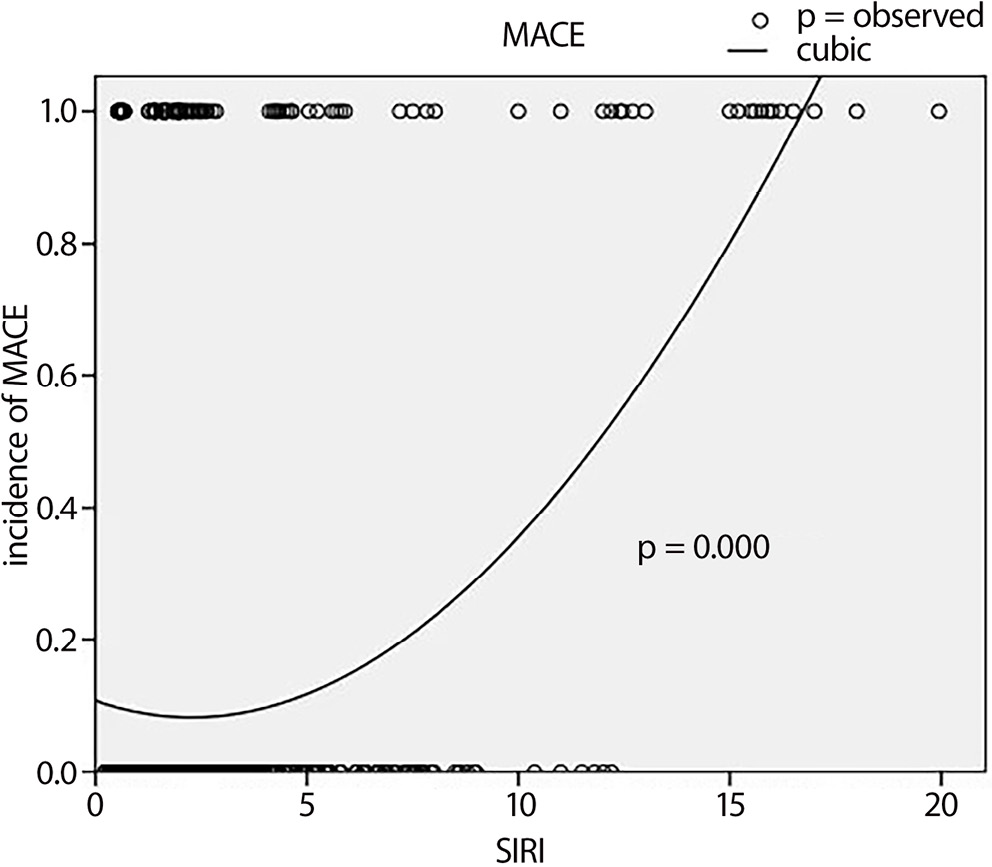

SIRI and MACE

The curve-fitting method was used to explore the relationship between the SIRI and MACEs in the older group (Figure 1). The SIRI was positively associated with MACEs (p < 0.001). Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards model analyses revealed that the SIRI (hazard ratio (HR): 1.209, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.147–1.274, p < 0.001) was an independent predictive risk factor for MACEs in the >60-year-old group. Additionally, age (HR: 1.080, 95% CI: 1.048–1.114, p < 0.001), hypertension (HR: 2.108, 95% CI: 1.364–3.258, p = 0.001), diagnosis of AMI (HR: 1.648, 95% CI: 1.023–2.657, p = 0.040), and heart rate (HR: 1.020, 95% CI: 1.007–1.032, p < 0.001) were associated with MACEs in patients aged >60 years (Table 4).

Further subgroup analyses for associations of the SIRI with MACEs were performed for the AMI and non-AMI subgroups. In the entire ACS group, 1,056 patients were diagnosed with AMI on admission (AMI group) and 702 were not (non-AMI group). During the observation period, a total of 126 (11.9%) MACEs were recorded in the AMI subgroup (nonfatal AMI: 28 cases; nonfatal stroke: 17 cases; all-cause death: 81 cases) and 39 (5.6%) MACEs were recorded in the non-AMI subgroup (nonfatal AMI: 13 cases; nonfatal stroke: 14 cases; all-cause death: 12 cases). The incidence of MACEs was significantly greater in the AMI subgroup (11.9% compared to 5.6%, p < 0.001). Patients with an AMI had significantly greater SIRIs than those without an AMI (3.1 ±2.4 compared to 1.3 ±0.9, p < 0.001). According to the univariate and multivariate Cox model analyses, the SIRI was found to independently predict the occurrence of MACEs in both the AMI subgroup (HR: 1.213, 95% CI: 1.155–1.274, p < 0.001) and the non-AMI subgroup (HR: 1.469, 95% CI: 1.192–1.812, p < 0.001). (Table 5, Table 6)

Discussion

The present study revealed that the incidence of recurrent MACEs and the SIRI were significantly greater in the older group than in the younger group. The SIRI was positively associated with MACEs and was an independent predictive risk factor for MACEs in patients aged >60 years with ACS after coronary angioplasty. The SIRI was significantly associated with age, hypertension, AMI, number of diseased vessels, and platelet count in all ACS patients. Similar relationships between the SIRI and MACEs were also observed in ACS patients with and without AMI.

Immune and inflammatory responses play crucial roles in the progression of atherosclerosis19, 20 and are related to the recurrence of cardiovascular events in ACS patients.21, 22 White blood cell subtypes have been found to aggressively participate in immune and inflammatory responses and CAD.23 Neutrophils not only infiltrate the ischemic myocardium and cause a destructive inflammatory reaction but also secrete inflammatory mediators, chemotactic substances and anaerobic free radicals to cause endothelial cell damage and subsequent tissue ischemia.20 The neutrophil count is associated with plaque rupture and thrombosis formation by exacerbating vessel wall inflammation and cell apoptosis.24, 25 Conversely, lymphocytes are involved in the regulatory pathway of the immune system and inflammation through lymphocyte apoptosis26 and thus play an antiatherosclerotic role. Lymphopenia is correlated with MACEs and a poor prognosis in ACS patients.27, 28 Monocytes promote atherosclerosis progression by adhering to the vascular endothelium and transforming into macrophages, activating pro-inflammatory cytokine and reactive oxygen species (ROS) release, stimulating platelets, and being involved in thrombosis and blockage of blood vessels.29, 30 The elevation of monocytes was independently associated with the risk of cardiovascular events.31, 32 The SIRI, which integrates 3 leukocyte subtypes, could better reflect the status of inflammation and the immune system in the body and is more sensitive than the components alone. An increase in the SIRI implies an increase in the number of neutrophils and/or monocytes and/or a decrease in the number of lymphocytes. Several studies have shown that the SIRI is related to the prognosis of the general population and cardiovascular patients. A study involving 42,875 adults revealed that the SIRI was closely associated with cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality in the general population and individuals older than 60 years.33 Another study from the Kailuan cohort demonstrated that an elevated SIRI increased the risk of stroke and all deaths and was associated with the incidence of MI.16 Dziedzic et al. confirmed that the SIRI was related to the severity of CAD and the diagnosis of ACS or stable CAD.15 Lin et al. showed that the SIRI was independently associated with the presence of atrial fibrillation in patients with ischemic stroke.17 An association between SIRI and MACEs was also suggested for patients with ischemic heart failure who underwent PCI.34, 35 The mechanisms underlying the relationship between SIRI and MACE may include elevated SIRI levels reflecting an imbalance between proatherogenic and antiatherogenic immune networks, which may promote plaque vulnerability, endothelial dysfunction and thrombotic events, consequently contributing to the occurrence of acute coronary events.20 The present study focused on patients older than 60 years with ACS after PCI. The SIRI was greater in elderly patients, and the incidence of MACEs was positively correlated with the SIRI. The SIRI was demonstrated to be an independent predictive risk factor for MACEs in patients aged >60 years with ACS. This may be explained in part by the following reasons: older patients commonly have more than 1 chronic disease. Inflammation is linked to aging and chronic disease.36 Additionally, senescent cells that accumulate in elderly patients have a unique senescence-associated secretory profile that includes many pro-inflammatory cytokines.37 Moreover, immune function declines during aging, and many immune cell types senescence with aging, resulting in a senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Together, these factors lead to more aggressive immune and inflammatory processes in elderly patients,38, 39 which can lead to poorer outcomes. Similar analyses were conducted for the AMI and non-AMI subgroups at the same time. In the ACS group, patients with AMI had a greater SIRI than did patients without AMI. This may be due to the higher grade of immune and inflammatory responses to more serious myocardial damage, microvascular obstruction and activation of the immune system in AMI than in unstable angina. Cox regression analysis revealed that the SIRI independently predicted the occurrence of MACEs in both the AMI and non-AMI subgroups, as well as in the elderly subgroup. The exploration of potential factors affecting the SIRI revealed that the SIRI was significantly associated with age, hypertension, diagnosis of AMI, number of diseased vessels, and platelet count. All of these results may indicate that immune-inflammatory responses play pivotal roles in the occurrence of MACEs. It is more effective in elderly patients, AMI patients and patients with hypertension or multi-vessel disease. Targeted anti-inflammatory therapy is potentially beneficial for reducing the incidence of cardiovascular events and improving patient outcomes. Additionally, the SIRI could be used as an indicator for identifying high-risk patients for intensive therapy to further reduce MACEs.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the study that should be considered. First, the data came from 1 medical center and included a relatively small number of participants. Thus, a large multicenter study with a longer follow-up time is necessary to confirm the results. Second, not enough confounding factors were taken into account. For example, pro-inflammatory and/or inflammatory cytokines were not evaluated as part of a multivariable Cox regression analysis, which may affect the clinical prognosis. The results from the present study should be extended in further research.

Conclusions

The present study revealed that the SIRI was an independent predictive risk factor for MACEs in patients >60 years of age with ACS and ACS with or without an AMI after stent implantation over 3 years of follow-up. The SIRI can be used as an indicator for identifying high-risk patients for intensive therapy to further reduce MACE in the era of PCI.